America’s Censored Classrooms 2022

PEN America Experts:

Director, State and Higher Education Policy

Sy Syms Managing Director, U.S. Free Expression Programs

Educational gag orders are state legislative efforts to restrict teaching about topics such as race, gender, American history, and LGBTQ+ identities in K–12 and higher education. PEN America tracks these bills in our Index of Educational Gag Orders, updated weekly.

In this report, we analyze the landscape of educational gag orders as of August 2022—a natural point for reflecting on the year’s legislation. Most state legislatures meet during the first half of the year; additional educational gag orders could become law before the end of 2022 via special sessions or in the few legislatures that meet year-round. However, the work of the vast majority of state legislatures has concluded until 2023.

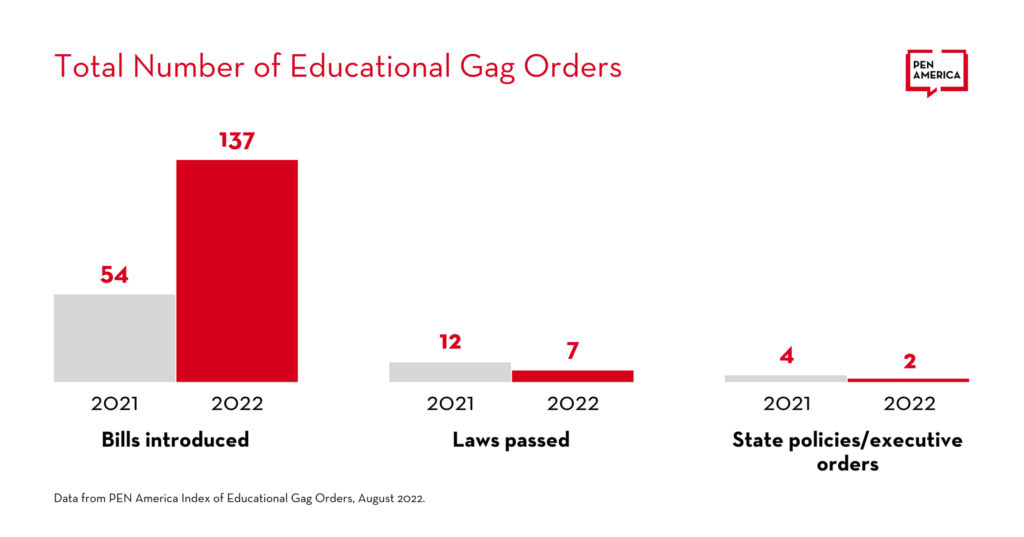

- This year, proposed educational gag orders have increased 250 percent compared to 2021. Thirty-six different states have introduced 137 gag order bills in 2022, compared to 22 states introducing 54 bills in 2021. While there has been a decline in new gag order laws passed from 12 last year to 7 this year, overall, legislative attacks on education in America have been escalating—fast.

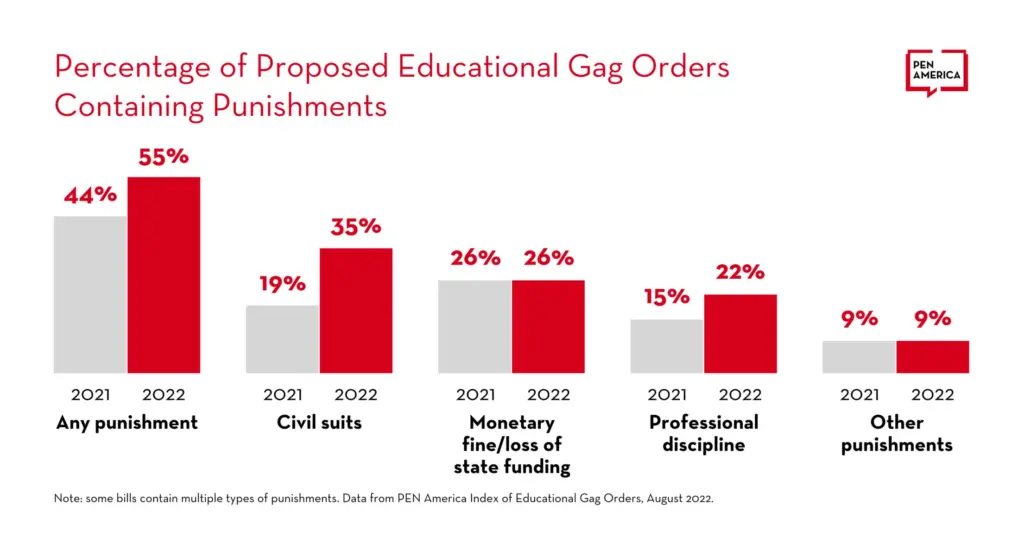

- This year’s bills have been strikingly more punitive. In 2022, proposed gag orders have been more likely to include punishments, and those punishments have more frequently been harsh: heavy fines or loss of state funding for institutions, termination or even criminal charges for teachers.

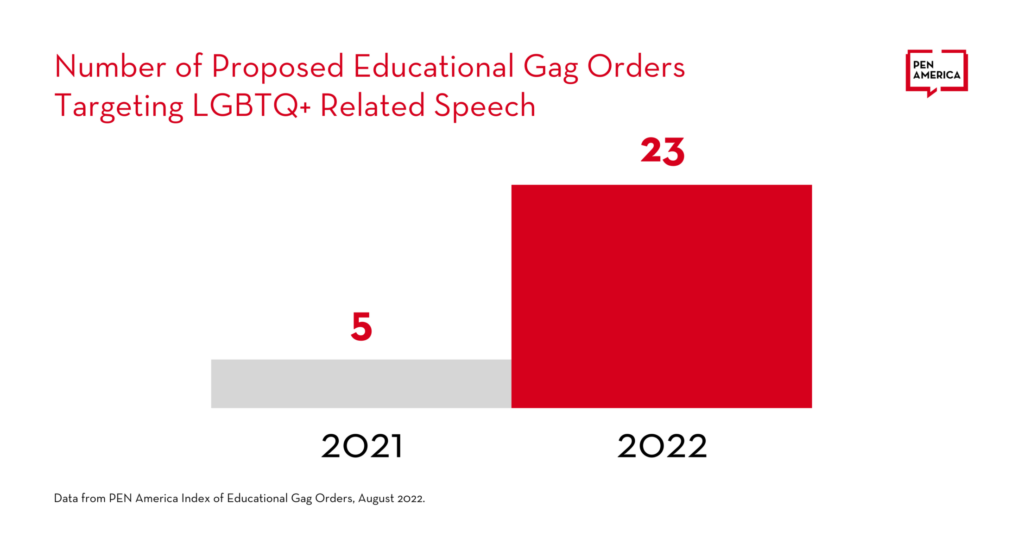

- While most gag order bills have continued to target teaching about race, a growing number have targeted LGBTQ+ identities. This includes Florida’s HB 1557—the so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bill—and 22 others. Attacks on LGBTQ+ identities have increasingly been at the forefront of educational censorship.

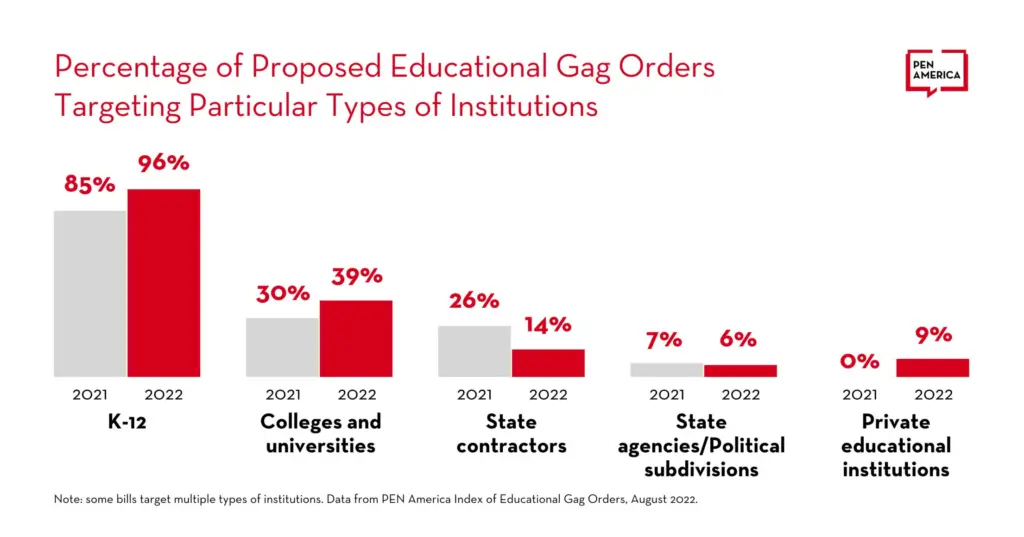

- Bills introduced this year have targeted higher education more frequently than in 2021, part of a broader legislative attack on colleges and universities. Thirty-nine percent of bills in 2022 have targeted higher education, compared with 30 percent last year. At the same time, bills focused on diversity trainings at government agencies have decreased. Educational gag order bills have become focused almost entirely on educational institutions. And for the first time, some bills have targeted nonpublic schools and universities, too.

- Consistent with last year’s trends, Republican legislators have overwhelmingly driven this year’s educational gag order bills. Only one bill out of the 137 introduced so far this year has had a Democratic legislative sponsor. Just a few years ago, Republican legislators were championing bills protecting free expression on college campuses; many are now focused on bills that censor the teaching of particular ideas.

- Meanwhile, conservative groups and education officials are working to broaden the interpretation of existing gag order laws. Lawsuits have begun to appear that ask courts to interpret gag orders as broadly as possible, while state boards of education have handed down draconian penalties in excess of what the laws require.

- In 2023, we anticipate that the assault on education will continue. More gag order bills will be filed in states where they failed narrowly this year. Based on current trends, we predict that other legislative attacks on education, such as “curriculum transparency” bills, anti-LGBTQ+ bills, and bills that mandate or facilitate book banning are also likely to increase.

Introduction

There is a legislative war on education in America. At the heart of this war are educational gag orders—state legislative attempts to restrict teaching, training, and learning in K–12 schools and higher education. These bills, which generally target discussions of race, gender, sexuality, and US history, began to appear during the 2021 legislative session and quickly spread to statehouses throughout the country. By the year’s end, 54 bills had been filed in 22 states, of which 12 became law.

In 2022, these battles have intensified.

Since the start of this year, lawmakers in 36 different states have introduced a total of 137 educational gag order bills, an increase of 250 percent over 2021. Only seven new gag order bills have become law so far this year, but these include some of the most censorious laws to date. And the dramatic increase in the number of bills introduced is itself a cause for alarm, reflecting a heightened inclination toward censorship. Bills introduced in 2022 have tended to be more punitive, to target a greater number of educational institutions, and to restrict a wider array of speech. The entire year can be summarized in a single word: escalation.

Proponents of educational gag orders often claim that they are necessary to avoid “indoctrination” of students. We disagree. . . . The restrictions and chilling effects of gag order laws threaten to destroy the climate of open inquiry required in free and democratic educational institutions.

This report offers a deep dive into what these bills say and how they operate. It builds on PEN America’s 2021 report on educational gag orders, as well as the PEN America Index of Educational Gag Orders, a comprehensive dataset, updated weekly, of every gag order bill introduced since January 2021.1PEN America, Educational Gag Orders: Legislative Restrictions on the Freedom to Read, Learn, and Teach, November 2021, https://pen.org/report/educational-gag-orders/; PEN America Index of Educational Gag Orders, https://airtable.com/appg59iDuPhlLPPFp/shrtwubfBUo2tuHyO. Taken as a whole, this report represents the most detailed legislative analysis available of educational gag order bills and laws at a national level, including the specific content being targeted by legislators, new strategies in gag order design, and the emerging dangers that these bills pose to freedom of speech, thought, and access to information. Bills that have become law in 2022, as well as executive orders enacted this year, are singled out for special analysis in Section I.2Note: To avoid confusion regarding bills introduced in 2022 and those introduced in 2021 but considered in both years of a legislative session, we have omitted dates from the bills referenced in footnotes. Except where otherwise noted, each bill referenced was considered in 2022.

A note on the scope of this report: PEN America recognizes that public education is a public good, subject to public debate, deliberation, and oversight; that a wide range of stakeholders should have a say in our educational system; and that views will vary regarding which materials and courses are of legitimate educational value. Our aim is not to take a position on the pedagogical benefits or drawbacks of specific curricular materials, educational approaches, intellectual frameworks, or professional trainings. Our serious concerns are about gag orders, and constitute neither an endorsement of specific wholesale curricula nor a rejection of the concerns of parents, teachers, and others with a stake in public education.

As a literary and human rights organization, our chief concern is with state censorship of the free flow of ideas, and with government restrictions on the freedom to read, to learn, and to teach. Proponents of educational gag orders often claim that they are necessary to avoid “indoctrination” of students. We disagree. As discussed below, the vagueness and overbreadth of these laws pose significant constitutional issues; they are hardly an effective tool. Instead, the restrictions and chilling effects of gag order laws threaten to destroy the climate of open inquiry required in free and democratic educational institutions.

While state governments and school boards do have leeway to set curricular standards, it has also been recognized by the Supreme Court that in doing so they should reflect democratic principles and retain space for dissent. In the words of Justice William J. Brennan, writing for the majority in Keyishian v. Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York (1967), schools must not “cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom.”3Keyishian v. Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York, 385 US 589 (1967), https://www.thefire.org/first-amendment-library/decision/keyishian-et-al-v-board-of-regents-of-the-university-of-the-state-of-new-york-et-al/. Writing for the plurality in Board of Education, Island Trees Union School District No. 26 v. Pico (1982), Brennan further elaborated that public schools must operate “in a manner that comports with the transcendent imperatives of the First Amendment.”4Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District No. 26 v. Pico, 457 US 853 (1982), https://www.thefire.org/first-amendment-library/decision/board-of-education-island-trees-union-free-school-district-no-26-et-al-v-pico-by-his-next-friend-pico-et-al/.

We stand resolute that educational gag orders violate these precepts and ought to be opposed and reversed. As we stated in 2021,

The teaching of history, civics, and American identity has never been neutral or uncontested, and reasonable people can disagree over how and when educators should teach children about racism, sexism, and other facets of American history and society. But in a democracy, the response to these disagreements can never be to ban discussion of ideas or facts simply because they are contested or cause discomfort. As American society reckons with the persistence of racial discrimination and inequity, and the complexities of historical memory, attempts to use the power of the state to constrain discussion of these issues must be rejected.5PEN America, Educational Gag Orders: Legislative Restrictions on the Freedom to Read, Learn, and Teach, November 2021, https://pen.org/report/educational-gag-orders/

Finally, this report analyzes patterns among not only educational gag orders that have become law, but also those that were introduced in 2022 and failed, or that remain pending in state legislatures at the time of publication. Many such bills are close relatives of others that passed or nearly passed; others are messaging bills introduced in blue states where they were unlikely to advance. A few died thanks to effective politicking by their opponents; this list includes multiple gag order bills in Indiana, which were defeated in 2022 amid political gaffes, citizen pressure, and disagreements among Republican legislators over whether the bills went too far or not far enough.6Stephanie Wang and Aleksandra Appleton, “How Indiana’s Anti-CRT Bill Failed Even with a GOP Supermajority,” Chalkbeat Indiana, March 10, 2022, https://in.chalkbeat.org/2022/3/10/22971488/indiana-divisive-concepts-anticrt-bill-failed-gop-supermajority/. A few more failed because of the vagaries of chance. These include West Virginia’s SB 498, where lawmakers failed by just minutes to meet the end-of-session deadline, and Arizona’s SB 1412, where one state senator’s absence on the last day of the session prevented the bill from becoming law.7Liz McCormick and Suzanne Higgins, “‘Anti-Racism Act’ Fails in Final Moments of 2022 Legislative Session,” West Virginia Public Broadcasting, March 13, 2022, https://www.wvpublic.org/government/2022-03-13/anti-racism-act-fails-in-final-moments-of-2022-session; “Arizona Legislature Updates: Lawmakers Adjourn for Final Time after Passing Water, School Voucher Bills,” Arizona Republic, June 25, 2022, https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/legislature/2022/06/22/arizona-budget-updates-lawmakers-turn-attention-deal/7707801001/.

While successful legislation is the greatest threat to classroom free expression, the avalanche of proposed bills that did not pass are also worthy of both attention and concern. Such bills evince a desire among lawmakers to censor educators in more places and using more extreme measures than they have done already, and they contain provisions that stand a good chance of being reintroduced in 2023. They also create a broad chilling effect among teachers and professors both by their pervasiveness and by the censorious discourse they inspire—part of a nationwide campaign of classroom censorship that shows no signs of abating.

The 2022 State Legislative Sessions in Review

Educational Gag Orders Passed in 2022

| State and Name | Institutions Targeted | Educational Topics Affected |

| Florida HB 1557 | Public K-12 | LGBTQ+ issues and identities |

| Florida HB 7 | Public K-12 and higher education, public and private employers* | Race, sex, color, national origin |

| Georgia HB 1084 | Public K-12 | Race, US history |

| Kentucky SB 1 | Public K-12 | Race, US history and culture |

| Mississippi SB 2113 | Public K-12 and higher education | Race, sex, ethnicity, religion, national origin |

| South Dakota HB 1012 | Public higher education | Race, color, religion, sex, ethnicity, national origin |

| Tennessee SB 2290 | Public higher education | Race, sex |

The most striking development to date in 2022 has been the sheer volume of bills introduced. In the month of January alone, 18 different educational gag order bills were filed in Missouri, 8 in Indiana, and 6 in Arizona (including 1 amendment to the state constitution). By the time most legislative sessions wound down in June, virtually every state where Republicans control at least one legislative chamber had considered an educational gag order in 2022. The only exceptions were Arkansas, which had already passed a gag order the previous year, and states whose legislatures do not meet in 2022.8Arkansas SB 627, https://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/Acts/FTPDocument?path=%2FACTS%2F2021R%2FPublic%2F&file=1100.pdf&ddBienniumSession=2021%2F2021R.

Consistent with last year’s trends, Republican legislators have been the driving force behind educational gag order bills. Only one bill introduced from January-August 2022 has had a Democratic sponsor: Arizona’s HB 2634, which would have prohibited public K–12 schools from using any instructional materials “reflecting adversely” on certain groups of people—a standard so broad that it could have legitimated all manner of censorship.9PEN America, “Failed Bill Brought by Arizona Democrats Would Have Restricted What Teachers Can Teach,” July 5, 2022, https://pen.org/press-release/failed-bill-brought-by-arizona-democrats-would-have-restricted-what-teachers-can-teach/. But this bill was filed only two days before the end of the Arizona legislative session and never had any chance of passage. Every other gag order bill introduced in 2022 across the country has been written and sponsored exclusively by Republican legislators.

Compared to last year’s crop, the gag order bills introduced thus far in 2022 have tended to be more expansive and to target a wider array of educational speech than those filed last year. Instruction related to race has been the most common category of speech to draw lawmakers’ attention, which was true in 2021 as well. But this year has also seen a sharp increase in the number of bills targeting LGBTQ+ issues and identities; 23 such bills have been introduced since the beginning of the year, and one, Florida’s HB 1557, became law. Overall, there has also been an increase in the complexity and scale of legislation, as lawmakers have sought to assert political control over everything from classroom speech to library content, from teachers’ professional training to field trips and extracurricular activities.

Another notable development to date in 2022 has been the growing number of bills targeting higher education. Of the 137 educational gag order bills introduced, 39 percent have targeted colleges and universities, compared to 30 percent of those filed in 2021. Of the bills that have become law thus far in 2022, 57 percent target higher education, compared with just 25 percent of the new laws last year. There has also been a significant increase in the number of bills designed to regulate non-public educational institutions, including private universities.

Finally, the bills introduced this year have been much more punitive. Thus far in 2022, 55 percent of bills have contained some kind of explicit punishment for violations, compared to 44 percent in 2021. Moreover, those punishments have tended to be more extreme, including private rights of action, large monetary fines, faculty termination, and loss of institutional accreditation. Some unsuccessful bills have even proposed criminal penalties.

In our 2021 report, we stated that educational gag orders demonstrate “a disregard for academic freedom, liberal education, and the values of free speech and open inquiry that are enshrined in the First Amendment and that anchor a democratic society.” We also argued that they “are likely to disproportionately affect the free speech rights of students, educators, and trainers who are women, people of color, and LGBTQ+.”10PEN America, Educational Gag Orders: Legislative Restrictions on the Freedom to Read, Learn, and Teach, November 2021, https://pen.org/report/educational-gag-orders/. These trends continue in 2022.

Outline

This report consists of six sections. In Section I, we survey the seven educational gag order laws and two executive orders enacted in 2022. In Section II, we discuss the types of educational institutions targeted by gag order bills this year. In Section III, we delve into the design of these bills, focusing on overall structure and the ways legislators have sought to regulate educational content. In Section IV, we analyze the content of the bills themselves, exploring the shifting priorities and objectives of their advocates and supporters. Section V discusses penalties and punishments, an area where there has been considerable evolution since 2021.

Finally, in Section VI, we discuss trends we are likely to see going forward, including:

a. another wave of educational gag order bills, especially in Republican-controlled legislatures;

b. a greater focus in educational gag order bills on restricting higher education, nonpublic educational institutions, and LGBTQ+ content;

c. litigation by both opponents and supporters of educational gag orders; and

d. a broader spectrum of educational censorship, including so-called “curriculum transparency” bills, reporting hotlines, legislation facilitating book bans and undermining tenure and academic freedom, and lawsuits designed to force maximal interpretations of existing gag order laws.

SECTION I: Laws and Executive Orders Enacted in 2022

Of the 137 legislative gag order bills introduced in 2022, seven have become law. Additionally, two executive orders that achieve similar ends have gone into effect. These laws and executive orders are summarized below.

Laws

Florida HB 155711Florida HB 1557, https://legiscan.com/FL/bill/H1557/2022.

- Targets: public K–12 schools

- Type of prohibition: inclusion

- Type of punishment: private right of action

- Legal challenges: Equality Florida v. DeSantis [pending]; Cousins v. the School Board of Orange County [pending]12Equality Florida v. DeSantis, 4:22cv134 (2022), https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/21564702-equality-florida-et-al-v-desantis-et-al-complaint; Cousins v. the School Board of Orange County, 6:22cv1312 (2022), https://www.lambdalegal.org/sites/default/files/legal-docs/downloads/cousins_fl_20220726_complaint.pdf.

This law prohibits public schools from offering any classroom instruction related to sexual orientation or gender identity prior to grade 3, or in grades thereafter in a manner “that is not age appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” Additional requirements related to “curriculum transparency” are also included. Parents who believe that a school has violated the law may file a complaint with the commissioner of education or sue the school in civil court.

Florida HB 713Florida HB 7, https://legiscan.com/FL/bill/H0007/2022.

- Targets: employers, public K–12 schools, public colleges and universities

- Type of prohibition: inclusion, promotion, compulsion

- Type of punishment: monetary fine, loss of state financial support

- Legal challenges: Falls v. DeSantis [pending], Honeyfund.com v. DeSantis [pending]14Falls v. DeSantis, 4:22cv166 (2022), https://aboutblaw.com/2G4; Honeyfund.com v. DeSantis, 4:22cv227 (2022), https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/22065949-1-complaint-honeyfund-v-desantis.

This law includes three principal provisions. The first prohibits all employers, including both public and nonpublic educational institutions, from requiring an individual to attend, as a condition of “certification, licensing, credentialing, or passing an examination,” any training or instruction where ideas from a list of “divisive concepts” about race, sex, color, or national origin are espoused, promoted, advanced, inculcated, or imposed.15Most of these bills include some or all of the “divisive concepts” listed in President Trump’s September 2020 executive order on “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping.” The list is common across most bills, with some adaptation. See Executive Order 13950, “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping,” September 22, 2020, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/28/2020-21534/combating-race-and-sex-stereotyping. Employers who do so may be fined up to $10,000 per violation under Florida’s Civil Rights Act. The second provision extends this same prohibition to classroom instruction in public K–12 schools, colleges, and universities. In the case of public K–12 schools, no punishment is specified. However, under a separate law passed shortly after HB 7, public colleges and universities found to have violated this prohibition may lose access to state financial support.16Florida SB 2524, https://legiscan.com/FL/text/S2524/id/2548804. The third provision requires that all instruction and supporting materials in public K–12 schools be “consistent” with a list of principles related to race, color, national origin, religion, disability, or sex—principles that essentially contradict the prohibited ideas enumerated elsewhere in the law. Teachers may not “indoctrinate or persuade” students to adopt any belief inconsistent with these principles. No punishment is specified.

Georgia HB 108417Georgia HB 1084, https://legiscan.com/GA/bill/HB1084/2021.

- Targets: public K–12 schools

- Type of prohibition: promotion

- Type of punishment: loss of institutional autonomy, professional discipline

- Legal challenges: none

This law prohibits public K–12 schools from adopting or engaging in any curriculum, classroom instruction, or mandatory training program that promotes ideas from a list of “divisive concepts” related to race. School districts found to have violated this law may be subject to additional state control, and superintendents of such school districts may be suspended.

Kentucky SB 118Kentucky SB 1, https://legiscan.com/KY/text/SB1/id/2569767.

- Targets: public K–12 schools

- Type of prohibition: inclusion, promotion

- Type of punishment: none specified

- Legal challenges: none

This law requires public K–12 schools to provide instruction that is “consistent” with ideas related to race, sex, US history and society, and human nature, including the idea that “defining racial disparities solely on the legacy of [slavery] is destructive to the unification of our nation.” Any instruction about “current, controversial topics related to public policy or social affairs” must be “relevant, objective, nondiscriminatory, and respectful to the differing perspectives of students.” No punishment is specified.

Mississippi SB 211319Mississippi SB 2113, https://legiscan.com/MS/bill/SB2113/2022.

- Targets: public K–12 schools, public colleges and universities

- Type of prohibition: compulsion

- Type of punishment: none specified

- Legal challenges: none

This law prohibits public K–12 schools, colleges, and universities from “direct[ing] or otherwise compel[ling]” students to “adopt, affirm, or adhere to” ideas from a list of “divisive concepts” related to sex, race, ethnicity, religion, or national origin. These educational institutions are also forbidden from making any “distinction or classification of students” on the basis of race. No public funds may be spent for any purpose that would violate this law.

South Dakota HB 101220South Dakota HB 1012, https://legiscan.com/SD/bill/HB1012/2022.

- Targets: public colleges and universities

- Type of prohibition: compulsion

- Type of punishment: none specified

- Legal challenges: none

This law prohibits public colleges and universities in South Dakota from compelling students to adopt or affirm certain ideas from a list of “divisive concepts” related to race, color, religion, sex, ethnicity, or national origin. It also bars these institutions from requiring students or employees to attend any training or orientation where these ideas are taught or promoted. No public funds may be spent for any purpose that would violate this law.

Tennessee HB 267021Tennessee HB 2670, https://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/Billinfo/default.aspx?BillNumber=HB2670&ga=112.

- Targets: public colleges and universities

- Type of prohibition: inclusion, compulsion

- Type of punishment: private right of action

- Legal challenges: none

This law prohibits public colleges and universities from conducting any mandatory student or employee training that includes ideas from a list of “divisive concepts” related to race, sex, religion, creed, nonviolent political affiliation, social class, or any other “class of people,” or that “promotes resentment” of any such group. For the purposes of this law, “training” includes “seminars, workshops, trainings, and orientations,” which under some interpretations could include classroom instruction. Public colleges and universities may not compel students or employees to adopt these ideas, or condition hiring, tenure, promotion, or graduation on whether a student or employee endorses a “specific ideology or political viewpoint.” Individuals who believe this provision has been violated may pursue legal remedy in an appropriate court. The law contains a likely unenforceable savings clause stating that it is not to be interpreted to infringe on an individual’s academic freedom or First Amendment rights.

Executive Orders

South Dakota Executive Order 2022-222South Dakota Executive Order 2022-2, https://governor.sd.gov/doc/GovNoem-K12CRT-EO.pdf.

- Targets: public K–12 schools

- Type of prohibition: promotion, compulsion

- Type of punishment: none specified

- Legal challenges: none

This executive order prohibits public K–12 schools from promoting any ideas “in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” including ideas from a list of “divisive concepts” related to race, color, religion, sex, ethnicity, or national origin. No punishment is specified.

Virginia Executive Order 123Virginia Executive Order 1, https://www.governor.virginia.gov/media/governorvirginiagov/governor-of-virginia/pdf/74—eo/74—eo/EO-1—ENDING-THE-USE-OF-INHERENTLY-DIVISIVE-CONCEPTS,-INCLUDING-CRITICAL-RACE-THEORY,-AND-RESTORING-EXCELLEN.pdf.

- Targets: public K–12 schools

- Type of prohibition: compulsion

- Type of punishment: none specified

- Legal challenges: none

This executive order prohibits public K–12 schools from directing or otherwise compelling students to adopt or affirm any ideas “in violation of Title IV and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” including a list of “divisive concepts” related to race, skin color, ethnicity, sex, or religion. No punishment is specified. Separate from the executive order, Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin created an email tip line for members of the public to report violations.

SECTION II: Types of Institutions Targeted

As in 2021, the vast majority of educational gag order bills introduced this year have targeted K–12 schools. Of those bills introduced, 132, or 96 percent, have trained their sights on primary and secondary education, including classroom instruction, faculty and staff trainings, invited speakers, school libraries, field trips, and extracurricular activities.

Beyond K–12 schools, a growing number of bills have targeted public colleges and universities. Last year, 30 percent of educational gag order bills targeted public higher education. In 2022, that number has increased to 39 percent, several of which, like South Dakota’s HB 1012, focus exclusively on higher education.24South Dakota’s HB 1012 became law in 2022. South Dakota HB 1012, https://legiscan.com/SD/bill/HB1012/2022.

This trend represents something of an about-face for many Republican lawmakers, who just four or five years ago were enthusiastically touting so-called Campus Free Speech Acts purportedly designed to protect intellectual diversity and free expression.25Such campus free speech laws have continued to pass in 2022—for instance Georgia’s HB 1, the “Forming Open and Robust University Minds Act.” See PEN America, “Chasm in the Classroom: Campus Free Speech in a Divided America,” 2019, https://pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2019-PEN-Chasm-in-the-Classroom-04.25.pdf, and Georgia HB 1, https://legiscan.com/GA/text/HB1/2021. Now many are targeting higher education with some of the most censorious language to date.

One of the most prominent examples in 2022 of a law that restricts higher education is Florida’s HB 7. Officially titled the Individual Freedom Act, the law prohibits public K–12 schools, colleges, and universities from “subject[ing] any student or employee to training or instruction that espouses, promotes, advances, inculcates, or compels such student or employee to believe” a list of concepts related to race, color, national origin, or sex.

This provision poses a threat to college and university faculty members’ First Amendment rights. “To impose any strait jacket upon the intellectual leaders in our colleges and universities,” Supreme Court chief justice Earl Warren declared in Sweezy v. New Hampshire (1957), “would imperil the future of our Nation.” The constitutional freedom of public university faculty to “espouse,” “promote,” and “advance” whatever ideas they view as relevant to their scholarship or course content is integral to the academy’s mission; “otherwise,” wrote the court, “our civilization will stagnate and die.”26Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 US 234 (1957), https://www.thefire.org/first-amendment-library/decision/sweezy-v-new-hampshire-by-wyman-attorney-general/.

HB 7 also deals a significant blow to academic freedom. For example, one of the concepts that HB 7 prohibits faculty from espousing is that “an individual, by virtue of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin, should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment to achieve diversity, equity, or inclusion.” By any reasonable interpretation, HB 7 makes it illegal in the state of Florida for a law professor to articulate arguments in favor of affirmative action in the classroom—even though affirmative action exists and is currently held by the Supreme Court to be constitutional in some forms.27Regents of University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), https://www.oyez.org/cases/1979/76-811. Recent guidance issued by the Florida Board of Governors and various state universities has not allayed these concerns.28Florida Board of Governors, 10.005 Prohibition of Discrimination in University Training or Instruction, https://www.flbog.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/10.005-Prohibition-of-Discrimination-in-University-Training-or-Instruction.pdf; University of Florida, “Understanding House Bill 7,” https://media.coip.aa.ufl.edu/public_live/hb7/presentation_html5.html; Northwest Florida State College, “HB7,” https://cdn.muckrock.com/foia_files/2022/06/20/HB_7_Circle_5.3.22.pdf; University of North Florida, “House Bill 7 (2022) Restrictions on Training/Instruction—Requirements & Action Plan,” https://www.muckrock.com/foi/jacksonville-326/hb7-impact-university-of-north-florida-129928/?#file-1023523.

Tennessee’s HB 2670, which also became law this year, goes further. It forbids public colleges and universities from including certain “divisive concepts” in a seminar, workshop, training, or orientation.29Tennessee HB 2670, https://legiscan.com/TN/text/HB2670/id/2502636/Tennessee-2021-HB2670-Draft.pdf. Educational gag orders that contain prohibitions on inclusion of certain concepts (analyzed at length in Section III) are typically the most censorious, forbidding even neutral and objective discussions of particular ideas. For example, under the law, public universities in Tennessee may no longer discuss in a seminar or assign for an orientation any material that “promotes division between, or resentment of, a race, sex, religion, creed, nonviolent political affiliation, social class, or class of people.” This provision could be construed to mean that a historian of the US civil rights era or of the Holocaust cannot include in a course historical sources that might inspire “resentment” of the Ku Klux Klan or the Nazis, each of whom might be considered a “class of people,” a term that is not defined.

These concerns are not far-fetched. In a lawsuit challenging HB 7, a University of Central Florida professor explained that he no longer felt free under the law to discuss with his students Michelle Alexander’s 2010 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, which argues that the American justice system perpetuates a racial caste system.30Falls v. DeSantis, 4:22cv166 (2022), https://aboutblaw.com/2G4. According to the professor, Alexander’s argument violates HB 7’s rule against promoting the view that “[a] person’s . . . status as either privileged or oppressed is necessarily determined by his or her race.” In their response, lawyers for the state of Florida acknowledged this example but argued that the professor could still discuss The New Jim Crow so long as he did so objectively and without endorsement. “Is that really all the First Amendment offers,” wrote the judge hearing the case in his decision denying the government’s motion to dismiss, “that you can speak all you want as long as you toe the government line?”31Judge Mark E. Walker, “Order Granting in Part and Denying In Part Motion to Dismiss,” Falls v. DeSantis, 4:22cv166 (2022), https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.flnd.430092/gov.uscourts.flnd.430092.68.0.pdf.

This year has also brought a sharp increase in the number of bills targeting nonpublic educational institutions. In all of 2021, only one bill (Louisiana’s HB 564) sought to regulate speech in such institutions. By contrast, 13 bills have done so in 2022, though most have been unsuccessful.32The full list of such bills includes: Alaska HB 391, https://legiscan.com/AK/text/HB391/id/2525369/Alaska-2021-HB391-Introduced.pdf; Florida HB 7, https://legiscan.com/FL/bill/H0007/2022; Georgia SB 613, https://legiscan.com/GA/text/SB613/id/2542860/Georgia-2021-SB613-Introduced.pdf; Indiana HB 1134, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/HB1134/id/2464216/Indiana-2022-HB1134-Introduced.pdf; Indiana HB 1231, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/HB1231/id/2465267/Indiana-2022-HB1231-Introduced.pdf; Iowa SF 2043, https://legiscan.com/IA/text/SF2043/id/2478845/Iowa-2021-SF2043-Introduced.html; Kentucky HB 487, https://legiscan.com/KY/text/HB487/id/2513646/Kentucky-2022-HB487-Introduced.pdf; Maryland HB 1256, https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2022RS/bills/hb/hb1256F.pdf; Mississippi HB 1492, https://legiscan.com/MS/text/HB1492/id/2493751/Mississippi-2022-HB1492-Introduced.html; Mississippi HB 437, https://legiscan.com/MS/text/HB437/id/2465352/Mississippi-2022-HB437-Introduced.html; Ohio HB 616, https://legiscan.com/OH/text/HB616/id/2562626/Ohio-2021-HB616-Introduced.pdf; South Carolina H 4605, https://legiscan.com/SC/text/H4605/id/2450490/South_Carolina-2021-H4605-Introduced.html; and Tennessee HB 2313, https://legiscan.com/TN/text/HB2313/id/2500053/Tennessee-2021-HB2313-Draft.pdf. These bills have adopted new and creative enforcement mechanisms designed to overcome the fact that nonpublic schools and universities are better shielded constitutionally against government curricular dictates. These mechanisms, as well as the bills more generally, are discussed at length in Section IV.

Finally, lawmakers in 2022 seem to have lost their appetite for regulating speech and conduct in nonschool settings. The original model for most educational gag orders, President Trump’s September 2020 Executive Order 13950 on “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping,” focused primarily on trainings in federal agencies and military academies, but not in other K–12 or higher education institutions.33Executive Order 13950, “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping,” September 22, 2020, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/28/2020-21534/combating-race-and-sex-stereotyping.

Whereas last year it was quite common for gag order bills to target state agencies, political subdivisions, and state contractors, reference to these institutions has been more or less absent in bills introduced this year. Thanks in part to a perception that Glenn Youngkin won the Virginia governor’s race in November 2021 by campaigning against critical race theory in schools, most 2022 educational gag order bills have focused on educational settings—that is to say, they have aimed to restrict students’ education.34 Amanda Becker, “Republicans See Schools as 2022 Political Battleground,” 19th (website), March 23, 2022, https://19thnews.org/2022/03/republicans-schools-2022-political-battleground-election/.

School Libraries

School libraries have emerged this year as especially tempting targets for lawmakers. For instance, Oklahoma’s SB 1142 and SB 1654 would have prohibited public school libraries from including on their shelves any book that makes as its “primary subject” LGBTQ+ issues or identities.35Oklahoma SB 1142, https://legiscan.com/OK/drafts/SB1142/2022; Oklahoma SB 1654, https://legiscan.com/OK/drafts/SB1654/2022. Other bills introduced in 2022 have proposed to strip certain exemptions from obscenity laws currently enjoyed by public school libraries, placing the institutions in legal jeopardy for granting students access to materials dealing with sex or sexuality. Some bills have proposed something similar for public (non-school) libraries as well.36Idaho HB 666, https://legiscan.com/ID/drafts/H0666/2022; Indiana SB 167, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/SB0167/id/2462721/Indiana-2022-SB0167-Introduced.pdf; Indiana HB 1134, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/HB1134/id/2464216/Indiana-2022-HB1134-Introduced.pdf; Indiana SB 17, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/SB0017/id/2494649; Indiana HB 1097 (2021), https://legiscan.com/IN/text/HB1097/id/2463727/Indiana-2022-HB1097-Introduced.pdf; Indiana SB 288 (2021), https://legiscan.com/IN/bill/SB0288/2021; Iowa SF 2198, https://legiscan.com/IA/drafts/SF2198/2021; Iowa HF 2261, https://legiscan.com/IA/drafts/HF2261/2021; Iowa SF 2364, https://legiscan.com/IA/drafts/SF2364/2021; Iowa HF 274, https://legiscan.com/IA/drafts/HF274/2021; Nebraska LB 282, https://legiscan.com/NE/drafts/LB282/2021. And Tennessee’s HB 2666, which became law, created a government commission that will have final say over which books a school district may ban from its library in cases where district-level decisions are appealed.37Tennessee HB 2666, https://legiscan.com/TN/drafts/HB2666/2021.

Some educational censorship bills contain provisions designed to make it easier to challenge and remove library content that offends an individual’s sensibilities. For example, Florida’s HB 1467, which became law in 2022, contains two important provisions relevant for school librarians. First, it allows any parent or resident of the county to challenge a library book on the grounds that it is “pornographic,” “not suited to student needs and their ability to comprehend the material presented,” or “inappropriate for the grade level and age group for which the material is used.” If the school district finds that the challenge is justified, the offending materials must be removed. Second, the law requires school districts to collect these challenges, regardless of their merit or outcome, and report them to the commissioner of education. The Department of Education will then publish a list of these challenges and disseminate them to schools across the state.38 Florida HB 1467, https://legiscan.com/FL/text/H1467/id/2545742; PEN America, “These 4 Florida Bills Censor Classroom Subjects and Ideas,” March 17, 2022, https://pen.org/these-4-florida-bills-censor-classroom-subjects-and-ideas/. The likely consequence is that school districts will avoid stocking controversial material.

In another example, after Utah’s HB 374, “Sensitive Materials in Schools,” became law this year, the state attorney general’s office issued a guidance directing school districts “to immediately remove books from school libraries that are categorically defined as pornography under state statute.”39Utah HB 374, https://legiscan.com/UT/drafts/HB0374/2022; Sean D. Reyes, “Official Memorandum—Laws Surrounding School Libraries,” June 1, 2022, https://attorneygeneral.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/2022-06-01-Official-Memo-Re-Laws-Surrounding-School-Libraries.pdf. In July, Alpine School District in Utah announced a plan to remove 52 books in response to this guidance.40PEN America, “Ban on 52 Books in Largest Utah School District Is a Worrisome Escalation of Censorship,” August 1, 2022, https://pen.org/press-release/ban-on-52-books-in-largest-utah-school-district-is-a-worrisome-escalation-of-censorship/.

Bills with such provisions are common in 2022. Not all of these bills are considered by PEN America to be educational gag orders, a term we reserve for legislation prohibiting the expression of certain ideas in a school or university. Nonetheless, the bills targeting school libraries are best understood as attempts to legalize book banning. For a more detailed analysis of recent book-banning trends, see PEN America’s April 2022 report, Banned in the USA.41PEN America, Banned in the USA: Rising School Book Bans Threaten Free Expression and Students’ First Amendment Rights, April 2022, https://pen.org/banned-in-the-usa/.

SECTION III: Types of Prohibitions

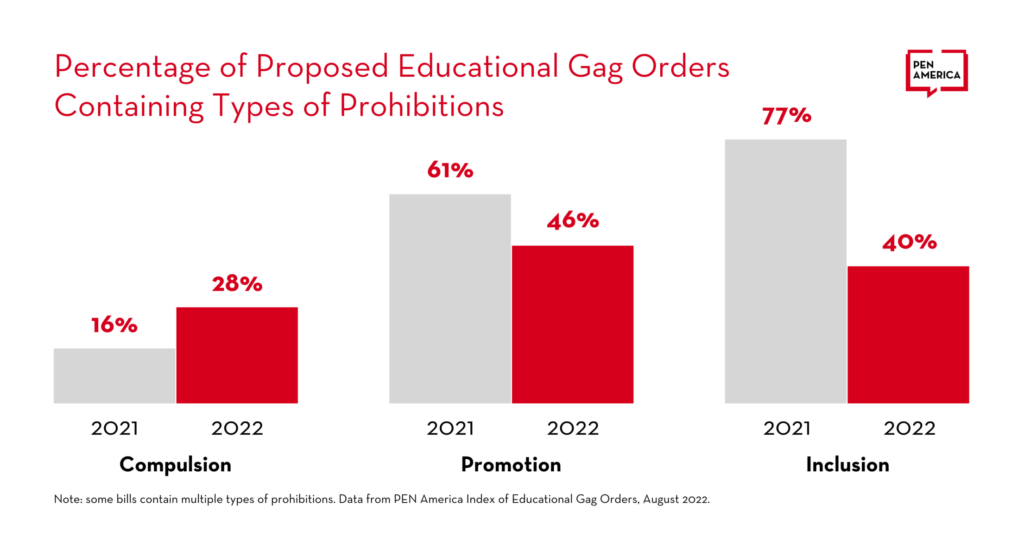

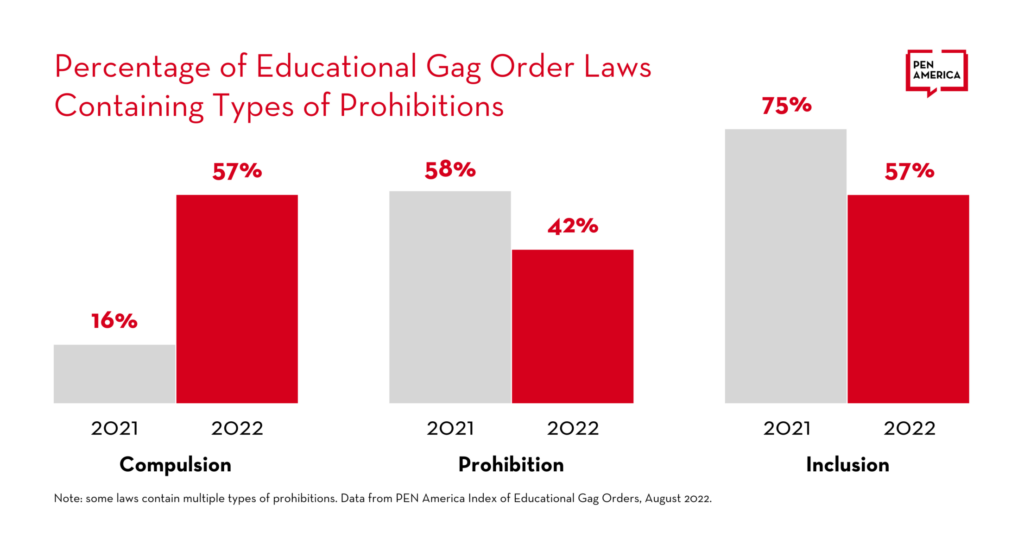

In broad terms, the educational gag order bills introduced since 2021 contain three distinct types of prohibitions: on compulsion, on promotion, and on inclusion of so-called “divisive concepts.” Many bills contain more than one of these prohibitions.

Prohibitions on Compulsion

These gag order bills would prohibit schools or universities from compelling individuals to adopt, affirm, or espouse a specific idea. For example, Idaho’s HB 377, which became law in 2021, states that no public university or school shall “direct or otherwise compel students to personally affirm, adopt, or adhere to” certain concepts related to sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin.42Idaho HB 377, https://legislature.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sessioninfo/2021/legislation/H0377.pdf. Missouri’s HB 1995 would have forbidden public schools from “compel[ling] a teacher or student to adopt, affirm, adhere to, or profess ideas in violation of Title IV or Title VI of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964.”43Missouri HB 1995, https://legiscan.com/MO/text/HB1995/id/2519671/Missouri-2022-HB1995-Comm_Sub.pdf. During 2022, bills with this type of prohibition became law in Mississippi and South Dakota.44Mississippi SB 2113, https://legiscan.com/MS/text/SB2113/id/2546132/Mississippi-2022-SB2113-Enrolled.html; South Dakota HB 1012, https://legiscan.com/SD/text/HB1012/id/2543182/South_Dakota-2022-HB1012-Enrolled.pdf.

Prohibitions on compulsion have increased significantly in 2022, appearing in 24 percent of bills compared to just 10 percent in 2021.

Prohibitions on Promotion

The second type of gag order bills would prohibit the promotion, endorsement, or inculcation of particular ideas or concepts. Florida’s HB 7 is a good example. It prohibits public universities and K–12 schools from “subject[ing] any student or employee to training or instruction that espouses, promotes, advances, [or] inculcates . . . such student or employee to believe” certain concepts about race, color, national origin, or sex.45Florida HB 7, https://legiscan.com/FL/bill/H0007/2022. Similarly, South Carolina’s H 4605 would have forbidden state-funded entities from “subject[ing] individuals to . . . instruction, presentations, discussions, or counseling that affirms or promotes” what the bill describes as “discriminatory concepts.”46South Carolina H 4605, https://legiscan.com/SC/text/H4605/id/2450490/South_Carolina-2021-H4605-Introduced.html.

A related set of bills would require that all instruction on controversial topics be “balanced” or “objective.” Many such provisions are adapted from the “Partisanship Out of Civics Act” model legislation developed by Stanley Kurtz, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.47Stanley Kurtz, “The Partisanship Out of Civics Act,” National Association of Scholars, February 15, 2021, https://www.nas.org/blogs/article/the-partisanship-out-of-civics-act. For instance, Texas’s SB 3, which became law in 2021, states that whenever public K–12 school teachers broach a “current event or widely debated and currently controversial issue of public policy or social affairs,” they must “strive to explore the topic from diverse and contending perspectives without giving deference to any one perspective.”48Texas SB 3, https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/872/billtext/pdf/SB00003E.pdf#navpanes=0. Missouri’s SB 694 would have required teachers to teach controversial topics “from both sides and without showing preference or deference to one perspective.”49Missouri SB 694, https://legiscan.com/MO/text/SB694/id/2453615/Missouri-2022-SB694-Introduced.pdf. And under Kentucky’s SB 1, which became law in April 2022, instruction must be “relevant, objective, non-discriminatory, and respectful to the differing perspectives of students.”50Kentucky SB 1, https://legiscan.com/KY/text/SB1/id/2569767.

The frequency of prohibitions on promotion this year has been virtually unchanged from 2021: 40 percent of bills have contained a ban on promoting certain types of ideas in 2022, compared to 39 percent in 2021.

Prohibitions on Inclusion

The final type of prohibition found in gag order bills would prohibit educators from “including,” “discussing,” or “making part of a course” certain topics or ideas in the curriculum, regardless of how objective or balanced the discussion is. For example, under Mississippi’s HB 437, public K–12 schools would have been unable to “include … divisive concepts as part of a course of instruction or in a curriculum or instructional material.”51Mississippi HB 437, https://legiscan.com/MS/text/HB437/id/2465352/Mississippi-2022-HB437-Introduced.html. A similar provision appears in Indiana’s SB 167, Indiana’s SB 415, and other proposed gag order bills.52Indiana SB 167, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/SB0167/id/2462721/Indiana-2022-SB0167-Introduced.pdf; Indiana SB 415, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/SB0415/id/2471417/Indiana-2022-SB0415-Introduced.pdf.

Other bills would achieve a similar effect via a different route. Instead of prohibiting the inclusion of certain concepts, they would require that instruction be “consistent” with those concepts’ ideological opposites. For instance, Kentucky’s SB 1, which became law in 2022, contains an Orwellian passage requiring that all “instruction and instructional materials” in public K–12 schools be “consistent with” the following “understanding”: “that the institution of slavery and post-Civil War laws enforcing racial segregation and discrimination were contrary to the fundamental American promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, as expressed in the Declaration of Independence, but that defining racial disparities solely on the legacy of this institution is destructive to the unification of our nation.”53Kentucky SB 1, https://legiscan.com/KY/text/SB1/id/2569767/Kentucky-2022-SB1-Chaptered.pdf. Similar “consistency” language can be found in Florida’s HB 7 and Rhode Island’s H 7539.54Florida HB 7, https://legiscan.com/FL/bill/H0007/2022; Rhode Island H 7539, https://legiscan.com/RI/text/H7539/id/2522893/Rhode_Island-2022-H7539-Introduced.pdf.

Inclusion bans have become less commonplace in bills introduced in 2022. Whereas half of all gag order bills contained a prohibition on inclusion in 2021, this year only 35 percent have contained such a prohibition.

Analysis

Of these three types of prohibitions—compulsion, promotion, and inclusion—those bills that prohibit inclusion are the most censorious. Where the bills have been implemented, it makes no difference how objectively a teacher discusses a given idea, or even whether they forcefully critique it. The mere fact of including that idea in the curriculum risks violating legislation in this category.

Yet there are many occasions in which a teacher would be justified in discussing a controversial topic or idea, even those that are racist or sexist. For instance, a history teacher might wish to assign, as part of a unit on the US Civil War, Alexander Stephens’s 1861 “Cornerstone Speech,” in which the Confederate vice president mounts a defense of slavery. Or a civics teacher might wish to discuss racism in the United States, citing by way of example the ideas of contemporary white supremacists. If these teachers work in a state with an inclusion ban, presenting such ideas in the classroom would put them at risk of violating the law.

The prohibitions on promotion are problematic as well. Such requirements may seem harmless, but in practical terms their vague, nonspecific language offers limitless opportunities for activists or administrators to claim teachers are in violation of such provisions.55PEN America, “For Educational Gag Orders, the Vagueness Is the Point,” April 28, 2022, https://pen.org/for-educational-gag-orders-the-vagueness-is-the-point/. As PEN America has previously explained, it is impossible to draw a clear line between teaching about a point of view and “promoting” that point of view. It is in the nature of education that some students will embrace and believe in at least some of the concepts taught. These prohibitions on promotion are in effect prohibitions on inclusion, albeit differently worded.56PEN America, Educational Gag Orders: Legislative Restrictions on the Freedom to Read, Learn, and Teach, November 2021, https://pen.org/report/educational-gag-orders/.

Similarly, no universally accepted distinction exists between a “balanced” presentation of material and a biased one; implementation of such requirements is essentially subjective, dependent on the interpretations of individual parents, administrators, or enforcement agencies. Heterodox Academy, an organization “deeply concerned about . . . an absence of viewpoint diversity” at the college level, has nevertheless opposed laws mandating balance in college classrooms; “legislation that takes this judgment away from intellectual communities,” they wrote in 2019, “threatens the ability of those communities to maintain order and advance pedagogical aims.”57Heterodox Academy, “On South Dakota’s HB 1087 and Legislating Viewpoint Diversity,” June 17, 2019, https://heterodoxacademy.org/blog/south-dakota-hb-1087-legislating-viewpoint-diversity/.

The damage these prohibitions may cause is especially clear for bills that target public colleges and universities, where the First Amendment protects the right of faculty members to teach in the classroom whatever idea they wish, provided it is germane to the overall subject matter of the course and delivered in a manner that complies with university policies. That right is also protected under the principles of academic freedom, both in public universities and in the vast majority of private colleges that have voluntarily undertaken to uphold academic protections. Without these freedoms, university educators would be unable to engage in rigorous scholarship or effective teaching, intervene critically in public debates, invite speakers representing a range of views to campus, or distinguish forcefully between truth and falsehood.

While governments have greater leeway to determine what is taught in K–12 schools, that does not mean that prohibitions on promotion are wise. For instance, how does one determine whether a teacher has illegally “promoted” an idea in the classroom? What one student views as a ringing endorsement might appear to another to be a straightforward description of facts. Faced with such ambiguity, the prudent teacher will be apt to self-censor.

Perhaps most ambiguous are the prohibitions on compulsion. On their face, by prohibiting compelled speech, these gag order bills appear to adhere to existing First Amendment doctrine. In West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), the Supreme Court struck down a state law requiring that public school students recite the Pledge of Allegiance. As Justice Robert H. Jackson declared in his majority opinion, “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in matters of politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word their faith therein.”58West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 US 624 (1943), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/319/624/#tab-opinion-1937809

According to some observers, these compulsion bills are relatively harmless, simply reinforcing the notion that speech cannot be compelled in schools. This seems to be the position of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), which has actively steered multiple state legislatures toward this formulation.59Greg Gonzalez, “FIRE Continues to Oppose Curricular Bans in Race and Sex Stereotyping Bills,” Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, July 11, 2022, https://www.thefire.org/fire-continues-to-oppose-curricular-bans-in-race-and-sex-stereotyping-bills/. But as FIRE itself acknowledges, “we have seen instances when universities misapply these laws,” and elected officials have done the same—either mistaking the definition of compulsion as constituting an outright ban on certain speech, or purposely misreading these laws in an effort to expand their prohibitions.

South Dakota’s HB 1012, which became law in 2022, is a good example of this phenomenon, and one mentioned specifically in a recent FIRE analysis. Though HB 1012 contains only compulsion language, Governor Kristi Noem commented after the law’s passage that it had “banned [critical race theory] in our universities.”60Dillon Burroughs, “Governor Kristi Noem Announces Executive Order Banning Critical Race Theory in Schools: ‘No Place in Our South Dakota Public Education,’” Daily Wire, April 5, 2022, https://www.dailywire.com/news/governor-kristi-noem-announces-executive-order-banning-critical-race-theory-in-schools-no-place-in-our-south-dakota-public-education. Such statements create a broad chilling effect on educators’ pedagogical choices by telegraphing that a ban of any type may be enforced as expansively as a particular official sees fit.61In a similar vein, whereas the text of Nebraska’s LB 1077 would have imposed restrictions only on “mandatory training,” its Republican sponsor explained that he intended “training” to include classroom instruction. Similar examples are common throughout discourse on gag orders and illustrate the expansive ways supporters would seek to enforce them. Sara Gentzler, “Bill Would Restrict How Nebraska Schools, Government Discuss Race and Sex,” Omaha World-Herald, January 18, 2022, https://omaha.com/news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/bill-would-restrict-how-nebraska-schools-government-treat-race-and-sex/article_d0bee4fe-7894-11ec-9b51-a71b3bf5e0e1.html. Educators might well conclude that a ban on compulsion will in practice be interpreted to mean something far more censorious than the plain language suggests.

In other proposed 2022 bills, the legislative text itself has conflated compulsion with persuasion or confusion. For instance, Illinois’s HB 5505 appears at first glance to have been a straightforward ban on compulsion. It states that no public school or university may “direct, require, or otherwise compel a student to personally affirm, adopt, or adhere to” certain ideas related to sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin. It also offers a list of remedies that a school may adopt when a teacher has been found guilty of compelling speech. Among them is that the teacher may “provide additional balance or factual basis, or correct any factual bases found to be incorrect or biased.”62Illinois HB 5505, https://legiscan.com/IL/text/HB5505/id/2495465/Illinois-2021-HB5505-Introduced.html.

Note that these two remedies (providing balance and correcting false claims) do not address a situation where a teacher is compelling student speech or belief. Rather, they address an entirely different situation, where a teacher is offering biased or factually incorrect instruction. Providing additional facts can no more remedy compelled speech than reading the Gettysburg Address can undo a mandatory recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance.

On the surface, educational gag orders that prohibit compelled speech may seem on relatively sound constitutional footing. But the potential for abuse is both obvious and inevitable. As PEN America explained in our 2021 report on educational gag orders, by identifying a specific set of beliefs disfavored by the state, these prohibitions on compulsion function as viewpoint-based prohibitions while masquerading as defenses of intellectual freedom.63PEN America, Educational Gag Orders: Legislative Restrictions on the Freedom to Read, Learn, and Teach, November 2021, https://pen.org/report/educational-gag-orders/.

In the current political climate, lawmakers and activists are primed to interpret many pedagogical practices, from “biased” instruction to true/false exams, as forms of compulsion. For that matter, compulsion laws could easily be used to block educators from asking their students to play devil’s advocate, engage in formal debate, or defend controversial viewpoints as part of a pedagogical exercise. In a less politically charged environment, these concerns might not be so salient. But for an educator in today’s climate, to be accused of compulsion even if such charges are spurious could lead to public uproar, an investigation, stigmatization, and other career-disrupting consequences. Accordingly, out of an abundance of caution, educators may reasonably act on the assumption that topics that are the subject of compulsion bans are best not even touched in the classroom.

SECTION IV: Types of Educational Content Targeted

As mentioned above, the first wave of educational gag order bills in 2021 were modeled on the Trump administration’s Executive Order 13950 on “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping,” which the Biden administration revoked in January 2021.64Executive Order 13950, “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping,” September 22, 2020, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/28/2020-21534/combating-race-and-sex-stereotyping; “President Biden Revokes Executive Order 13950,” Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, 2021, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ofccp/executive-order-13950. As its name suggests, this executive order regulated how federal agencies and contractors could discuss issues surrounding race and sex. Most state-level educational gag order bills in 2021 targeted similar topics, with a secondary focus on patriotism and US history.

For the most part, these trends have continued into 2022. The majority of this year’s bills have sought to regulate how educators discuss racism and sexism, though many have targeted systemic discrimination and issues of identity more generally. Many have also targeted instruction related to US history and contemporary American society. However, the greatest change this year has been a heightened focus on LGBTQ+ issues and identities—a development that resulted in the most highly-publicized educational gag order of the year, Florida’s HB 1557.

Ideas related to race, sex, and gender have continued to be the most common target of educational gag order bills.

Race, Sex, and Gender

Ideas related to race, sex, and gender have continued to be the most common target of educational gag order bills. Many still contain elements from the executive order on “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping,” but often with significant elaboration. For example, Rhode Island’s H 7539 would have prohibited teachers from using any “instructional material” that suggests an individual is “inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously, solely by virtue of his or her race or sex,” or that “an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, [bears] responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex.” All of this is copied more or less verbatim from Trump’s executive order.

But H 7539 then goes on to prohibit teachers from using terms such as “supremacy,” “racial guilt,” and “racial fragility.” Indeed, it includes a more general attack on “identity politics,” stating that “no exclusive focus or centering of curricula on the history, literature, current events, or cultural contributions of individual identity groups shall be permitted.” It also forbids teachers from making use of any “ideological materials, worksheets, homework, texts or assigned reading, and/or mentored discussions that depict identity groups as oppressors and/or victims.”65Rhode Island H 7539, https://legiscan.com/RI/text/H7539/id/2522893/Rhode_Island-2022-H7539-Introduced.pdf.

We see here how an earlier focused attack on instruction related to racism and sexism has transformed in 2022 into a more general assault on discussions of systemic inequality. Minnesota’s HB 3301, for instance, contains a similar provision, proposing to forbid teachers from requiring that students examine “the role of race and racism in society, the social construction of race and institutionalized racism, and how race intersects with identity, systems, and policies.”66Minnesota HF 3301, https://legiscan.com/MN/text/HF3301/id/2512231.

While none of these bills passed in 2022, similar bills could easily become law in the future. In 2021, the North Dakota legislature passed HB 1508 after just five days of debate. Consequently, it is now illegal in that state for public K–12 teachers to include any instruction suggesting that “racism is systemically embedded in American society and the American legal system to facilitate racial inequality.”67North Dakota HB 1508, https://www.ndlegis.gov/assembly/67-2021/special-session/documents/21-1078-03000.pdf. Language of this type, which has spread widely in 2022, would shut down important conversations in the classroom and would particularly imperil cultural and ethnic studies courses.

Shielding American history and society from negative moral judgments has been a major priority for lawmakers in 2022.

US History and Contemporary American Society

Another set of ideas targeted frequently by lawmakers in 2022 is speech deemed unduly critical of American history and of the United States today.68Many of the bills discussed here are explored in greater detail by PEN America in “Educational Gag Orders Seek to Enforce Compulsory Patriotism,” March 30, 2022, https://pen.org/update-educational-gag-orders-seek-to-enforce-compulsory-patriotism/. For instance, lawmakers have introduced 14 bills that explicitly limit use of the New York Times’s 1619 Project on the grounds that it identifies slavery as part of the nation’s “true founding.” Other bills have targeted similar historical perspectives that emphasize the deep roots of slavery in American history and society. South Carolina’s H 4392, for example, would have forbidden educators from making use of any instructional material that could lead students to believe that “slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality.”69South Carolina H 4392, https://www.scstatehouse.gov/sess124_2021-2022/bills/4392.htm.

Such bills may reflect an understandable desire to repudiate slavery as inimical to the ideals of equality and freedom extolled by the nation’s founders. In practice, however, they would outlaw historical perspectives that explore how racial discrimination and slavery were entrenched in the lives of the Constitution’s framers and the country they birthed. Similarly, when it comes to contemporary society, public schools do play an important role in fostering a healthy civic culture, imputing national ideals, and instilling an understanding and appreciation of students’ community and society. But legislation restricting what concepts and perspectives may be covered constricts classroom teaching and learning unreasonably. Education in a liberal society must include the examination of critical perspectives and alternative viewpoints, material that these bills would too often rule out of bounds.

Nevertheless, shielding American history and society from negative moral judgments has been a major priority for lawmakers in 2022. Rhode Island’s H 7539 states baldly that “history shall be taught using the standards, customs, and traditions in use at the time of the historical event.”70Rhode Island H 7539, https://legiscan.com/RI/text/H7539/id/2522893/Rhode_Island-2022-H7539-Introduced.pdf. New Hampshire’s HB 1255 sought to forbid teachers from promoting “any doctrine or theory promoting a negative account or representation of the founding and history of the United States of America in New Hampshire public schools which does not include the worldwide context of now outdated and discouraged practices.”71New Hampshire HB 1255, https://legiscan.com/NH/text/HB1255/id/2461346. And Oklahoma’s HB 2988 would have prohibited teaching that “America has more culpability, in general, than other nations for the institution of slavery”; that “America, in general, had slavery more extensively and for a later period of time than other nations”; or that one race “is the unique oppressor in the institution of slavery” while another is its “unique victim.”72Oklahoma HB 2988, https://legiscan.com/OK/text/HB2988/id/2452914.

Other educational gag order bills in this category have focused less on US history than on the current state of American society. Many bills in this category are notable for their brevity. A pair of Missouri bills (HB 2189 and SB 645) state simply that K–12 schools and colleges must offer courses that “promote an overall positive . . . understanding of the United States.”73Missouri HB 2189, https://legiscan.com/MO/text/HB2189/id/2464797; Missouri SB 645, https://legiscan.com/MO/text/SB645/2022. Two in Oklahoma (SB 588 and SB 614) would have prohibited “anti-American bias.”74Oklahoma SB 588, https://legiscan.com/OK/text/SB588/id/2442064/Oklahoma-2022-SB588-Introduced.pdf; Oklahoma SB 614, https://legiscan.com/OK/text/SB614/id/2447707/Oklahoma-2022-SB614-Amended.pdf. The bans in these bills are both pithy and absolute, with no elaboration on how these standards would be judged.

By contrast, other bills are much more labyrinthine. One Indiana bill states that students must be taught that

socialism, Marxism, communism, totalitarianism, or similar political systems are incompatible with and in conflict with the principles of freedom upon which the United States was founded. In addition, students must be instructed that if any of these political systems were to replace the current form of government, the government of the United States would be overthrown and existing freedoms under the Constitution of the United States would no longer exist. As such, socialism, Marxism, communism, totalitarianism, or similar political systems are detrimental to the people of the United States.[/mfn]Indiana HB 1040, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/HB1040/id/2462805/Indiana-2022-HB1040-Introduced.pdf.[/mfn]

And West Virginia’s HB 4016, which targets public K–12 schools, would have prohibited

the presentation or promotion of any political, economic, or political-economic system that is based on ideological concepts rooted in or inspired by Marxism, Marxist-Leninism, Maoism, socialism, communism, or so-called critical political theory or critical economic theory, of any form or intellectual tradition whatsoever without:

(A) The inclusion of the historically documented occurrences, scope and scale of state sponsored terror and murder, absence of legal process and protection of civil and political rights, forced labor, economic inefficiency, and starvations which have transpired under such forms of political economy; and

(B) the provision of equal pedagogical instruction time and student curricula material content dedicated to political-economic systems based in the western tradition of constitutional representative democracy;

(C) the preservation in law of civil, political rights, private property rights, intellectual property rights in constitutional representative democracies;

(D) the historically documented greater efficiency and productivity of free enterprise, and free market capitalism in constitutional representative democracies;

(E) the impact of monetary policy on pricing and inflation; and

(F) presentation of political spectrums as measured by the factors of state control versus individual liberty, regardless of economic model.75West Virginia HB 4016, https://legiscan.com/WV/text/HB4016/id/2500304/West_Virginia-2022-HB4016-Introduced.html.

Bills this elaborate remain uncommon, but they have appeared with much greater frequency in 2022 than in 2021.

The Don’t Say Gay bills are only the most visible aspect of a broader campaign by legislators in 2022 against discussion of LGBTQ+ issues in educational settings.

LGBTQ+ Issues and Identities

Finally, lawmakers have increasingly attempted to regulate whether and in what ways educators may expose students to LGBTQ+ issues and identities.76For more on this category of educational gag order bills, see PEN America’s analysis in “Educational Gag Orders Target Speech about LGBTQ+ Identities with New Prohibitions and Punishments,” February 15, 2022, https://pen.org/educational-gag-orders-target-speech-about-lgbtq-identities-with-new-prohibitions-and-punishments/ Twenty-three anti-LGBTQ+ bills that would censor classroom speech have been proposed in 2022, compared with just five in 2021. (Note that PEN America tracks only those anti-LGBTQ+ bills that censor speech in educational institutions; this is only a small fraction of the hundreds of anti-LGBTQ+ bills filed across the country in 2022. A comprehensive legislative tracker for those bills can be found at the ACLU’s website.77American Civil Liberties Union, “Legislation Affecting LGBTQ Rights across the Country,” July 1, 2022, https://www.aclu.org/legislation-affecting-lgbtq-rights-across-country.)

The most well-known example of an anti-LGBTQ+ educational gag order from this year is Florida’s HB 1557, referred to by its critics as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill. This law states that classroom instruction “on sexual orientation or gender identity may not occur in kindergarten through grade 3 or in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” The law also creates a private right of action, permitting a parent to sue a school it believes violated HB 1557 and recover damages in court.78Florida HB 1557, https://legiscan.com/FL/bill/H1557/2022.

HB 1557 was introduced in the Florida House of Representatives on January 11, 2022. Since then, copycat bills have been filed in many other states. For example, under Louisiana’s HB 837, public school teachers would have been unable to “cover the topics of sexual orientation or gender identity in any classroom discussion or instruction in kindergarten through grade eight” or to “discuss [their] own sexual orientation or gender identity with students” in any grade.79Louisiana HB 837, https://legiscan.com/LA/text/HB837/id/2550972/Louisiana-2022-HB837-Introduced.pdf. Ohio’s HB 616 would forbid them from teaching, using, or providing “any curriculum or instructional materials on sexual orientation or gender identity.”80Ohio HB 616, https://legiscan.com/OH/text/HB616/id/2562626/Ohio-2021-HB616-Introduced.pdf. Georgia’s SB 613 states that teachers in private schools would not be allowed to “promote, compel, or encourage classroom discussion” of sexual orientation or gender identity at any primary grade level.81Georgia SB 613, https://legiscan.com/GA/text/SB613/id/2542860/Georgia-2021-SB613-Introduced.pdf. And a pair of North Carolina bills, HB 755 and HB 1067, would have banned instruction on these topics until the fourth and seventh grades, respectively.82North Carolina HB 755, https://legiscan.com/NC/text/H755/id/2592056/North_Carolina-2021-H755-Amended.pdf; North Carolina HB 1067, https://legiscan.com/NC/text/H1067/id/2590617/North_Carolina-2021-H1067-Amended.pdf. Such bills would likely have ruled out a host of curricular content, including books with LGBTQ+ characters, history about LGBTQ+ rights movements, and more.

While none of these copycat bills have become law as of August 2022, several have come close, and more seem likely to be introduced in 2023. One bill with substantially similar language, Alabama HB 322, did become law, though it does not contain an explicit age or grade-based prohibition on speech.83Alabama’s HB 322, https://legiscan.com/AL/drafts/HB322/2022, states that any “classroom instruction regarding sexual orientation or gender identity” to students in grades K-5 must be provided “in a manner that is . . . age appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” This provision owes a clear debt to Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law, but in so far as it does not prohibit a category of speech—at least until the state standards change—we do not consider it an educational gag order.

The Don’t Say Gay bills are only the most visible aspect of a broader campaign by legislators in 2022 against discussion of LGBTQ+ issues in educational settings. South Carolina’s H 4605 would have forbidden public K–12 teachers from “subject[ing]” students to “controversial and age-inappropriate topics” such as “gender identity or lifestyles.”84South Carolina H 4605, https://legiscan.com/SC/text/H4605/id/2450490/South_Carolina-2021-H4605-Introduced.html. Indiana’s HB 1040 would have prohibited them from discussing “sexual orientation,” “transgenderism,” or “gender identity” without parental consent.85Indiana HB 1040, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/HB1040/id/2462805/Indiana-2022-HB1040-Introduced.pdf. (Note: the word “transgenderism” is generally considered offensive by the transgender community.)86“Glossary of Terms: Transgender,” GLAAD Media Reference Guide, 11th Edition, https://www.glaad.org/reference/trans-terms. As originally introduced, Kansas’s HB 2662 would have redefined the state’s obscenity law to make it a class B misdemeanor for a teacher to present in the classroom any depiction of homosexuality.87Kansas HB 2662, https://legiscan.com/KS/text/HB2662/id/2551295/Kansas-2021-HB2662-Amended.pdf. A similar provision was included in the original draft of Arizona’s HB 2495, https://legiscan.com/AZ/text/HB2495/id/2504467/Arizona-2022-HB2495-Engrossed.html, which prohibited public schools from using any “sexually explicit material” in the classroom. For the purposes of the bill, “homosexuality” was considered to be sexually explicit. And a slew of bills introduced this year in Oklahoma would have regulated whether public school libraries could stock books about LGBTQ+ issues; university professors could discuss “gender, sexual, or racial diversity, equality, or inclusion”; or teachers or professors could promote a position that contradicts a student’s sincerely held religious belief.88Respectively, Oklahoma SB 1142, https://legiscan.com/OK/text/SB1142/id/2533307/Oklahoma-2022-SB1142-Amended.pdf, and Oklahoma SB 1654, https://legiscan.com/OK/text/SB1654/id/2486020/Oklahoma-2022-SB1654-Introduced.pdf; Oklahoma SB 1141, https://legiscan.com/OK/text/SB1141/id/2460101/Oklahoma-2022-SB1141-Introduced.pdf; and Oklahoma SB 1470, https://legiscan.com/OK/text/SB1470/id/2484266/Oklahoma-2022-SB1470-Introduced.pdf, and Oklahoma HB 614, https://legiscan.com/OK/text/SB614/id/2447707/Oklahoma-2022-SB614-Amended.pdf.

This surge in anti-LGBTQ+ speech legislation reflects a growing alignment between different political efforts. Social conservatives, who object to LGBTQ+ identities on cultural or religious grounds, have long sought to regulate how educators discuss these matters but have had only limited success at the state legislative level. Their efforts have been boosted, however, by the loosely knit and much more recent “anti–critical race theory” campaign, whose advocates argue that much of what passes for instruction on LGBTQ+ topics in public schools constitutes a kind of left-wing indoctrination. Some have even gone so far as to liken such lessons to “grooming,” the action by a pedophile to prepare a child for sexual exploitation.89 Colby Itkowitz, “GOP Turns to False Insinuations of LGBTQ Grooming against Democrats,” Washington Post, April 20, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/04/20/republicans-grooming-democrats/. Over the past two years, the anti–critical race theory campaign has displayed remarkable energy and success in targeting classroom discussions of race and sex, as the 19 educational gag order laws passed in 15 states demonstrate. Now this campaign appears to have turned its attention to gender identity and sexual orientation as well.

The alignment of these efforts has in some instances breathed new life into efforts to enact bills restricting classroom expression about LGBTQ+ identities. Legislation of this type is not new; in Tennessee, for example, such bills have been introduced multiple times since 2013, without success.90“GLSEN Condemns Reintroduction of Tennessee’s ‘Don’t Say Gay,’” February 1, 2013, https://www.glsen.org/news/glsen-condemns-reintroduction-tennessees-dont-say-gay. But the energy of the newer anti-critical race theory campaign has helped such bills gain new momentum, becoming law in Florida and proliferating to other states.

SECTION V: Punishments