Ta-Nehisi Coates at the World Voices Festival

‘The first thing you attack when you want to strip people of their rights is the imagination’

By Lisa Tolin

Ta-Nehisi Coates says the current attack on books in the United States is one battle in a very long war.

“I think it’s really, really, really important that while we highlight what is going on right now, we do not paint America as though there was some golden age of literacy and freedom of speech. I don’t believe that has ever existed,” Coates told PEN America ahead of his Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Lecture.

“I would say the enemies of equality, the enemies of freedom, have always recognized that the first thing you attack when you want to strip people of their rights is the imagination, the ability to imagine those rights in the first place. And books are just an excellent, exceptional, maybe our best technology for conveying that.”

Coates, a National Book Award winner and MacArthur Fellow, hopes to contextualize the flurry of book bans and censorship across the United States in his lecture on May 11 at PEN America’s World Voices Festival. The event at the New School Tishman Auditorium will be live streamed.

In conversation with PEN America, Coates reflected on the current censorship that has caused his book Between the World and Me to be banned and excluded from history classes. (This interview has been condensed.)

How do you view the current book bans and censorship in classrooms and libraries?

I think it’s really, really important to contextualize what is happening today with the long sweep of American history and its relationship to books. And particularly, if I may be so direct, its relationship to African American literacy, which, from the moment we got here as enslaved people has always, always been under assault. There is not a period in American history where African American literacy enjoys the total and complete freedom and support of the state. That’s just not a tradition that I come from.

Frederick Douglass is someone who acquired the gift of literacy, and the gift of writing, in defiance of literally the destruction of his body. He was risking his life to acquire not even books, but scraps of paper, anything when he was young, that would help him acquire knowledge to read. As a journalist, also within my ancestry is Ida B Wells, who was run out of Memphis for daring to accurately and truthfully report on on lynching. In my ancestry is Elijah P. Lovejoy, Malcolm X, Carter G Woodson.

“There is not a period in American history where African American literacy enjoys the total and complete freedom and support of the state.”

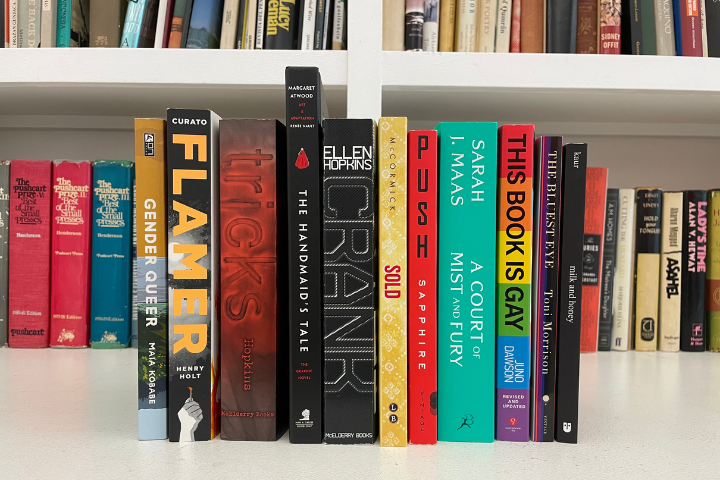

We are in a particular moment of a very, very, very long war. This has always been contentious, and I don’t want to present myself as though I’m going through something that is new and is unique. This has always been what it was. Toni Morrison — what is happening in Virginia with Toni — that’s not new. The Bluest Eye has been besieged for years, Beloved has been besieged for years. And so this is a continuation of a very, very, very long war.

We are counting more book bans now than even a year or two ago. What is it about this moment that you think is driving this frenzy?

I mean, if I was reductive, I think it’s Barack Obama. I think it’s the fact that this country had the imagination in 2008 to elect an African American president. And that shook so many things in the constellation, in the imagination of what America was.

You have to see the book bans in concert with the assault on all of these other things, with the assault on voting rights, for instance, with the assault on protests, and in Florida passing laws that allow folks to drive vehicles into protests and not be prosecuted, you have to see it all in concert all and working together. I would argue, you’ve got to see it in concert with these laws that increasingly stripped women of bodily autonomy.

I really, really believe that that election was a rupture, like a psychic, psychological rupture through this country, and we are still living in the wake of it. So even as I said this is the continuance of something that has been going on for a long time, a certain, determined minority in this country was not particularly prepared for everything that that wrought.

When politicians talk about CRT, or banning an AP course on African American history, what are they trying to do?

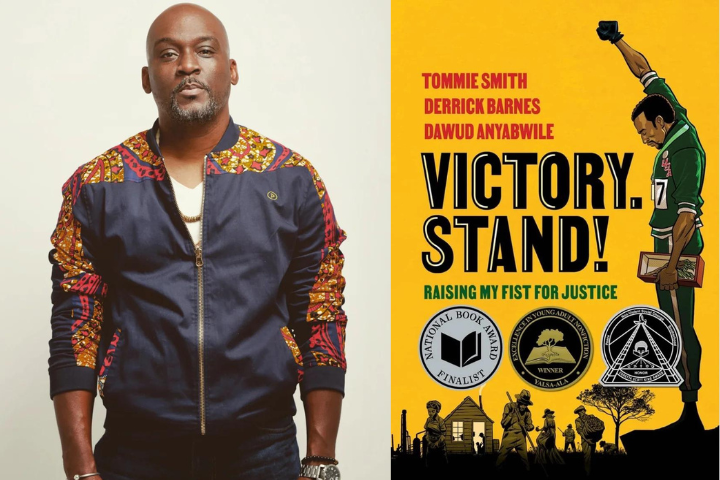

They are trying to counter the act of reimagining. That’s what this war is over. Because books don’t just sit with the author. And one of the changes that has happened over the past 20 years is books that come from these outsider communities don’t just sit and exist in those communities. My publisher, Chris Jackson, his house One World, there was a point in 2020, during the protests, where he had like, three of his authors on the bestseller lists, all three African American. What that means is that whole swaths of white people are consuming this.

“I think they have correctly identified literature as the font of imagination. And if you can constrict that … and then on top of that, if you can restrict their ability to to make political choices by restricting their ability to vote, then you got them at both ends, right?”

And so I think people like Ron DeSantis and Donald Trump, who hail from a political movement that seeks to constrain and constrict freedom when it pertains to people who don’t fit into their very narrow idea of what and who this country was built for, I think they have correctly identified literature as the font of imagination. And if you can constrict that, if you can siphon that off, if you can stop people from imagining things that exist beyond this narrow box, and then on top of that, if you can restrict their ability to to make political choices by restricting their ability to vote, then you got them at both ends, right? It’s a brilliant strategy. It’s intentional. I don’t think we’ve given it enough thought. I don’t think we’ve given it enough credit. I don’t think we ourselves comprehend the power of books. I think we say that a lot, but I think our foes understand it a lot better than we do.

What would you say to people who say books like yours are making white children uncomfortable?

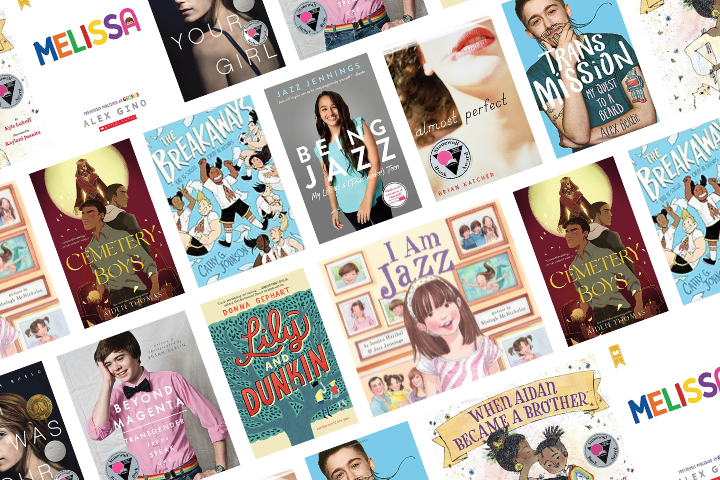

Am I allowed to curse? I would say in the oral tradition, taken from the great poem Shine and the Great Titanic, I would say, “get your ass in the water and swim like me.” Which is to say, this is our world. We’re uncomfortable every day. Being Black is to be existentially uncomfortable. Being a woman is to be existentially uncomfortable. Being LGBTQ, being trans is to be uncomfortable. That is the nature of human beings. It’s the nature of the human experience, and particularly for those who live outside of the mainstream.

People who simply seek comfort, and people who come to education of all things, to seek comfort, don’t make for good citizens. And they don’t really make for mature adults, honestly. I think maintaining an imagination as it pertains to humanity in the world is the least you can do. And protecting that imagination is the least you can do.

“I think maintaining an imagination as it pertains to humanity in the world is the least you can do.”

And so folks who feel like they’re made to reconsider their identity, or experience some level of psychic, emotional pain, I mean, this is the enlightened human experience. This is what it is. It’s not fun to realize that one day, everybody you know is going to die, and you too. That’s not fun. That makes me feel bad. But it’s an essential truth that has to be grappled with and has to be talked about and has to be thought about. People that come to history looking to feel comfortable and feel better about themselves, what kind of students are these people supposed to make?

I’m old enough to remember when students on college campuses were being attacked for seeking safe spaces, even now, being attacked for seeking trigger warnings. And now we have whole legislatures, governors, that seek to use the power of the state to turn schools into entire safe spaces for certain groups of people.

This is what it is, man. This is what it is. This is the human experience. Welcome to it.

You have talked in the past about the role of a writer vs the role of an activist. What do you think the writer’s role is in creating change?

I’m hesitant to come to comment on THE writer’s role. I can only think of what Black writers did for me, and I keep coming back to this same word, and that is imagination, and helping me understand what is possible. If you leave it up to the approved corpus of literature of the state and you’re Black, it’s very easy to wind up loathing yourself, hating yourself, detesting yourself. Because many of the myths, the ideas, the tropes that this country holds dear, the heroes, people that it worships, are not merely casually racist, but their racism is foundational to who they are. You can walk through the world and find yourself worshiping people and modeling yourself after people and telling stories about people who literally hated you.

You have to read when you’re born an outsider — you just have to — because you have to have some sort of independent idea of who you are as a person, or else you risk defining yourself through the lens of people whose status and privilege and material wealth and social wealth so greatly depend on your subjugation. And that’s just a really, really dangerous place to be.

I think the normal writer who maybe is not freighted with these sorts of things, is tasked with the very difficult job of imagination, conceiving something new that is different. That’s what we look for in great books. But the Black writer, the writer who comes from a subjugated group, does not just have to imagine, but has to reimagine, by which I mean, the tropes and ideas that we traditionally use as the ground, which serves as a kind of jumping off point for all our imaginative possibilities, don’t really exist for us. So we have to construct new ground. We have to construct new ideas. So, that’s a tough job.

What can people do to support you, or support free speech?

First of all, I’m fine. I sell a lot of books. Every time one of these folks does one of these things or I’m kicked off a list, I always sell a ton of books. So it’s not me I’m worried about. I am worried about the teachers in these districts. I’m worried about teachers who, in a few instances I know of, who are fired for teaching our work. I’m worried about parents who believe that a free and open public and school library system is essential to the intellectual development of their children. I’m worried about those children who don’t deserve to have their world constrained by narrow-minded people who have no imagination themselves, beyond power.

I think a lot of us were slow to recognize, because of the form it took when this first started, which I actually date back to President Donald Trump putting Nikole-Hannah Jones’s 1619 project in an executive order. It’s hard for me to remember a president condemning a journalistic enterprise in an executive order, with the force of the state, emanating from arguably the most powerful person in the world. And I think we were really slow on the uptake on that. And I think we should have been faster, been louder as writers. But I think the people most in need of support are the people on the ground, who are waging the fight.

Lisa Tolin is Editorial Director of PEN America.