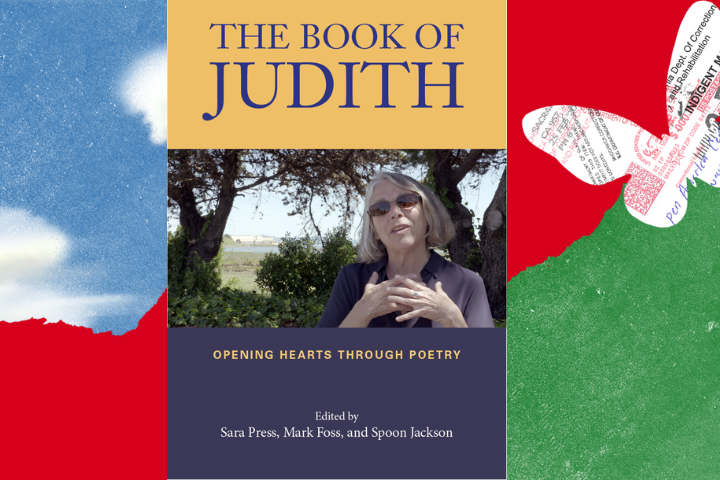

The Book of Judith: Honoring Judith Tannenbaum (1947-2019)

Two years ago, New Village Press published The Book of Judith: Opening Hearts Through Poetry, an anthology in remembrance of teaching artist Judith Tannenbaum, who dedicated her life to students in and out of prison. Tannenbaum’s career in education goes back to 1970, when she began teaching writing and literature in Berkeley, California. Moving across the state, she taught in public schools and community art centers, in addition to Santa Rosa Junior College and the University of California at Berkeley. For twenty years, Tannenbaum also served as faculty member and training coordinator of WritersCorps, a project of the San Francisco Arts Commission.

Working with thinkers and writers in prison was of great importance to Tannenbaum. In the mid-1980s, she began teaching with San Quentin with Arts in Corrections, a partnership between the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and the California Arts Council. Through her work with students in carceral spaces, she helped writers and artists explore the depths of their creativity. One of those students was Spoon Jackson, who she worked with at San Quentin in the 1980s before his work was recognized by the PEN Prison Writing Awards.

After Tannenbaum’s passing in 2019, Spoon Jackson collaborated with Tannenbaum’s daughter, Sara Press, and Mark Floss to edit The Book of Judith. In the preface to the book, Press writes:

My mom, Judith Tannenbaum, lived how she wanted to—until her body gave out. She had a strong vision for her life and could only live true to herself. Writing was a fundamental component of this. She was driven to see both the light and dark, and to see the whole from the individual parts. Toward the end, my mom urged me to keep my eyes and my heart open. This project was a way to do that.

The 33 contributors of reflective poetry, prose, essays, illustrations, and fiction in this collection testify to these attributes. To experience Judith Tannenbaum beyond this anthology, consider reading her books, which include the memoir Disguised as a Poem: My Years Teaching Poetry at San Quentin (Northeastern University Press, 2000), two books for educators, and six collections of poetry. With Spoon Jackson, she also co-authored Heart: Poetry, Prison, and Two Lives (New Village Press, 2010).

The following selections are contributions from some of Tannenbaum’s former students: Elmo Chattman, Jr., and Boston Woodward, and Spoon Jackson.

December

Judith Tannenbaum

Everywhere a pulse is beating:

in the straight trunk of the sequoia,

in the leafless oak,

in the sound of snow against digger pine.

A pulse: the madrone

with its smooth, pink flesh;

Orr Creek where downed redwood dangles roots;

the soil. Beating through things

and the names of things.

Black oak leaves caught in ice,

half-eaten body of the dead deer.

A pulse beating through Round Valley,

Potter Valley, Anderson, Redwood, Long Valley.

And in winter water that moves the world in rivers

named here Garcia, Navarro, Big, Russian, Eel.

All the forks of all these rivers,

all the falls and creeks and streams.

A pulse. A deep, drifting down.

Disguised as a Poem

Elmo Chattman, Jr.

In Birkenstocks and handcrafted earrings

still living a life from the sixties

you enter this place

this dungeon

this dust bowl on the edge of the bay

where 3,000 men wait

for the sweet rain called freedom.

You walk a path from the front gate

across the garden plaza

Your pale feet step softly

Upon the spots where angry men have died

Don’t let the pink and yellow roses fool you

This is not a pretty place.

Two flights down

you wait for us to come

bearing the fruits and scars of our embattled lives

disguised as poems

scrawled on bits of paper

last week

in a cell

when sleep was hard to find.

For three hours in that basement room

we are cut off

A million miles away

from your daughter and your cat

A hundred years from death row.

For three hours

we joust

we orbit around each other wrestling with words

we make love with words

we grow close

We meet in a place called poetry

one woman

and a few captured men

We speak of poems

and grasp at them like straws

until it is time to go.

Two flights up

the cool night air greets us

There are always those few tight minutes

waiting for the count to clear

and the inevitable parting of ways

We could go have coffee and speak of poems all night

but your daughter will miss you

and I must be back in my cell before ten.

It is always the same

For three hours

you or Phavia or Sharon or Scoop

manage to get close to me

only to be peeled away

like the bark from a young tree

leaving behind a little spot

bare and vulnerable

that does not want to see you go

but will die of exposure

long before you return.

Broken to Whole

Boston Woodard

I first met Judith while I was serving my sentence in San Quentin State Prison in 1985. She had only been there a couple of months when we met. Her supervisor was San Quentin’s arts facilitator, Jim Carlson, who oversaw all the Arts in Corrections (AIC) groups and programs that were becoming available for several years under his leadership. Jim arranged programs not only for the prisoners on San Quentin’s Main Line but for those in Administrative Segregation (the Hole), as well.

I was involved with the AIC through the music program in what is now called “the old Education Building.” That was where artists and teachers like Judith would gather with Jim to discuss art program matters. I remember Judith sorting papers, organizing supplies for her class, and making sure she made extra copies of her students’ poems so they could send them home to their families. She was a stickler for details regarding her agenda.

Judith’s poetry class was in one of several rooms downstairs. At the end of the hall were the institution’s TV control room and two band rooms full of music equipment. I spent most of my spare time practicing the bass guitar or learning new songs with my band. My friend Spoon Jackson was in Judith’s class and would encourage me to “check it out.” He knew I was also getting into writing, but it was strictly nonfiction. I told Spoon I couldn’t write a poem if my life depended on it. I asked Judith if I could sit in on her class if I stayed out of the way. She said I could come when I wasn’t in the band room. I was grateful for that.

I remember once Spoon opened the door to the band room and told me Judith was upstairs with cookies and that I’d better hurry up. She would bring homemade cookies every week for staff and her students. By the time I got to the AIC office, sure enough, all the cookies were gone. But on my way back down stairs, Judith handed me a napkin with several cookies wrapped inside. That was Judith. The cookie thing may seem trivial, but to a prisoner who rarely had something homemade, Judith’s cookies were a big deal.

Despite my misgivings, I did write some poems in Judith’s class. She would also allow me to write one-hundred- to three-hundred-word word pieces from prompts, which she critiqued for me. Many times she said, “Use your imagination, Boston; picture what you want to say in your head.” I do that to this day.

Through her class, I also overcame my biggest fear: public speaking. Every week she would have the guys read what they wrote from a small wooden podium in front of the class. It’s because of Judith and the encouragement of her students in San Quentin that I’m able to speak publicly today.

In 1986, I got a job as a clerk on San Quentin’s Death Row when it was located in C-Section. In 1988, Death Row was moved to East Block, where it is today. At that time, I was one of two prisoners from the Main Line allowed to go onto “the Row.” We got the job because we had no drugs on our records and were never part of a gang. During that time, Judith began working with men on the Row and in the Hole.

Lynnelle, another amazing AIC teacher, had been working with the condemned men for some time. She taught Judith the ropes on how to teach in such a high-security part of the prison. When either of them came to the Row, the door officer, “Chili,” would key them in, and allow me or the other clerk to help them with the boxes of approved art supplies. We were allowed to carry the supplies to the top of the stairs but no farther.

Judith almost always had a smile on her face. Even now when I reflect back on those days, it’s her smile I remember. When Judith was in teaching mode, she was all business. But her smile was infectious, putting everyone in a better mood. To many of the men, Judith was like a big sister. She treated everyone with equal respect.

In 1989, San Quentin State Prison was transforming into a lower-level institution. Spoon and I, and hundreds of others, were herded into buses and moved to the newly opened New Folsom State Prison. Judith was losing many students who had been with her for three to four years—students with whom she had come to develop a mutual respect and thoroughly enjoyed teaching. I know she left not too long after that.

I began writing articles and stories for various outside (free world) publications about what was going on behind prison walls. My book, Inside the Broken California Prison System, was published in 2011. The next year, Judith set up a reading from my book and those of three other prison authors—Spoon Jackson, Ken Hartman, and Jarvis Masters—at Litquake, which is San Francisco’s annual literary festival. Our friends and relatives read for us in what was the first time Litquake had ever included prisoner writings in the reading program. I will forever be grateful to Judith for that opportunity.

Twenty-four years after being in other prisons, I was transferred back to San Quentin as a low-custody-level prisoner when I had three to four years left on my sentence. Judith visited me several times during those final years. It was a short drive across the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge to San Quentin from her home, which made it easy for her.

During one of the last in-person conversations we had, I remember telling her I was nervous about finally getting out after so many years. She told me, “You got this, Boston, I promise you.” My life became much better with people like Judith Tannenbaum in it. She inspired me by example. I will never forget her.

I’ve been out going on four years now. I’m off parole and feeling good about my life. I work, and live in a nice home with a car and great friends. I am involved in community events and activities, and have become that contributing member to society Judith told me I would be.

You were right, Judith: I got this.

Fire

Spoon Jackson

Judith was like a fire

on a chilly morning

where we gathered around

and gained warmth

and insight

She ignited our fire

(at our core)

that often we did

not know we had

Fire she then gathered

around and gained

warmth and insight

Judith knew there was

something special

undiscovered

about each of us

Especially those of us

she allowed to be

closer to her

We all grew

like a stand of sequoias

sharing space

Judith Tannenbaum (1947–2019) was an educator, poet, writer, and speaker. She shared and taught poetry in schools and community centers, and was faculty with WritersCorps, a highly respected project that placed professional writers in community settings to teach creative writing to youth. Tannenbaum found a passion for prison justice and reform after teaching at San Quentin State Prison through the California Arts Council and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. She continued to give poetry workshops and performances in prisons and juvenile facilities nationally. Her memoir, Disguised as a Poem: My Years Teaching Poetry at San Quentin (Northeastern University Press, 2000), is considered essential reading for anyone wishing to teach art in prisons. Through her work at San Quentin, Tannenbaum fostered a 20-year-long friendship with poet Spoon Jackson, and the two recounted their lives and experiences in the double memoir, By Heart: Poetry, Prison, and Two Lives (New Village Press, 2010).

The late Elmo Chattman, Jr. (1957-2021) was incarcerated for thirty-three years within the California State Prison System. During his years at San Quentin, he was a student of Judith Tannenbaum. In 1989, he earned a B.A. degree in Journalism from Antioch University, becoming one of the first three students to earn an undergraduate degree while incarcerated in San Quentin State Prison in its 137-year history. Elmo was a published poet, short story writer, and served as a reporter and then editor of the San Quentin News.

Spoon Jackson is a poet serving a life sentence without possibility of parole. He is the author of numerous works, including the poetry collection Longer Ago, which was edited and published by Judith Tannenbaum. He and Judith co-wrote the memoir By Heart: Poetry, Prison, and Two Lives.

Boston Woodard is a writer, musician, literacy tutor, event organizer, and prisoners’ rights advocate. He is the author of Inside the Broken California Prison System (Humble Press, 2011).