The PEN Pod: On the Small Things We Cannot See That Change Our Lives with Ed Yong

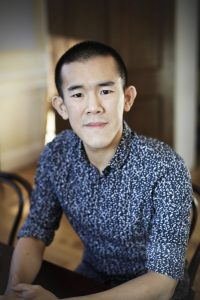

Today on The PEN Pod, we spoke with Ed Yong, a Washington, D.C.-based award-winning science journalist who reports for The Atlantic. His work has been featured in National Geographic, The New Yorker, WIRED, Nature, New Scientist, Scientific American, and many more publications. His first book, I Contain Multitudes, which was published in 2016 and became a New York Times bestseller, takes a close look at the amazing partnerships between animals and microbes. We spoke with Ed about the missed signals of the COVID-19 pandemic, what we can learn from microbes, and what gets left out of the national narrative about the virus.

Today on The PEN Pod, we spoke with Ed Yong, a Washington, D.C.-based award-winning science journalist who reports for The Atlantic. His work has been featured in National Geographic, The New Yorker, WIRED, Nature, New Scientist, Scientific American, and many more publications. His first book, I Contain Multitudes, which was published in 2016 and became a New York Times bestseller, takes a close look at the amazing partnerships between animals and microbes. We spoke with Ed about the missed signals of the COVID-19 pandemic, what we can learn from microbes, and what gets left out of the national narrative about the virus.

In 2018, you wrote a piece about America’s underpreparedness for the inevitably upcoming pandemic. What is it about medical crises like this that make us, as a nation, so complacent, at least at their outset?

I think we suffer from long-standing and universal psychological biases. When a crisis is knocking on our door, we panic and we throw all of our attention and resources at the problem, and then as soon as it fades, we lapse into neglect, we forget, we lower our guard. And that’s where I think the U.S. was at the start of this. It had many long-standing problems and vulnerabilities that the pandemic then exploited, many of which I discussed in that piece in 2018. Others I didn’t have now come to light, but it was all predictable in many ways. The way the pandemic has played out in the U.S.—a lot of people saw it coming, but I think the extent to which America really has been blinded in the face of this disaster is really surprising and really shocking.

How do you think the phenomenon of increasing media fragmentation that we’ve found ourselves in has influenced our current moment and our understanding of what’s happening?

It’s definitely made the pandemic harder to control, and it’s made it harder for people to get a crisp, clear understanding of what is happening. During a global crisis of this kind, you need clear and consistent communication from leaders and authority figures. You need those communications to be based on evidence, to be scientifically minded, and we haven’t had that—at least, we haven’t had that consistently. From the White House, we’ve had misleading statements. We’ve had Trump contradicting his own scientific advisors and frequently himself. From a hyper-partisan media, we’ve had false narratives about how the pandemic is not actually much of a problem, that it’s similar to flu—all these kinds of misstatements that made a certain portion of Americans lower their guard, feel less concerned, and be less prepared than they should have been.

“The way the pandemic has played out in the U.S.—a lot of people saw it coming, but I think the extent to which America really has been blinded in the face of this disaster is really surprising and really shocking.”

Almost everything in this country is highly polarized now, and the pandemic was no exception. It was no surprise that public health should be dragged into the same culture war that almost everything else is. That being said, I do think that it is remarkable how unified much of America was in the face of that—how the majority of people across the political spectrum agreed that social distancing was important, agreed that states should be careful about reopening again, agreed that masks were important and should be mandatory. And in those spaces, there is a huge amount of agreement that we really don’t see in a lot of other areas. While the partisan gap still exists and is clearly being driven by partisan news coverage, I think there is some hope and optimism to be found in this stereotypically individualist nation being remarkably prepared to act in the collective good.

I wanted to turn to this idea of interdependence and the fact that in this pandemic, we are finding that we are very connected in ways that we might not have thought of before. In your book, I Contain Multitudes, you present several fascinating examples of how microbes play a huge symbiotic role inside our bodies, helping us to shape and maintain our bodies and overall health. Why did you feel it was important for us to be aware of this relationship between human and microbial cells?

I wouldn’t say important—clearly, there are health implications there. I just think that it is a wonderful thing to know. It profoundly changes our understanding of our bodies, our behavior, and of the rest of the natural world if we understand how deeply microbes shape our lives. The book I wrote, I Contain Multitudes, was about the beneficial sides of that. Obviously, we are now seeing detrimental effects that microbes can wreak, but all that being said, I think the thread that unites them is that we, as a species, gravitate a little toward narcissism. We think that we are almighty and all-powerful, we have dominion over the world, and yet very small things that we cannot see and that we can barely study really, significantly, profoundly change our lives. Often for the better—mostly for the better, I think—but occasionally, considerably for worse. We need to appreciate that influence. We need to understand ourselves as part of this wider, deeper sense of nature.

“Almost everything in this country is highly polarized now, and the pandemic was no exception. It was no surprise that public health should be dragged into the same culture war that almost everything else is. That being said, I do think that it is remarkable how unified much of America was in the face of that—how the majority of people across the political spectrum agreed that social distancing was important, agreed that states should be careful about reopening again, agreed that masks were important and should be mandatory.”

In a way, it’s the inverse of the feeling of looking up at the night sky and pondering your smallness in terms of the larger universe. It’s sort of the opposite of that, where you’re looking at the universe that’s happening inside our bodies, which is really fascinating.

Yeah, absolutely. You’re totally right. That dizzying sense of scale is something that I’m really interested in in my writing. And that has fueled a lot of the interest.

Turning back to the pandemic, the ways in which the stories that we tell about our bodies also have huge implications for health policy. Recently, you wrote about the phenomenon of “long-haulers”—those affected by COVID-19 who have been dealing with their symptoms for at least a month or longer, and those experiences have really been left out of the narrative about COVID-19. Why do you think that is?

The partisanship we’ve already talked about, I think, is part of a broader tendency to dichotomize everything, to see everything as binaries with few shades of gray in the middle. We see that in the pandemic—how we think of people either as being dead or having recovered. These long-haulers who have been dealing with symptoms for many months fall into either category. We talk about, like you say, either severe cases that are bad enough to need oxygen, to need ventilators and care in an intensive care unit, or those that are mild—like the common cold. And again, these long-haulers are neither. Technically, their kind is mild because they aren’t on ventilators, and many have never been hospitalized, but many of them have been incapacitated for months. They cannot go about their normal lives. They have been pummeled by these rolling waves of really debilitating symptoms.

“The pandemic narratives we tell are much too simple and much too polarized—two worlds, two very stark extremes. . . as journalists, it is our responsibility to resist those easy dichotomies and to find all the missing nuance in the middle that is important, but is also being neglected.”

So you’re right, the pandemic narratives we tell are much too simple and much too polarized— two worlds, two very stark extremes. There’s a huge middle ground whose stories aren’t being told. Many of these long-haulers are young, they’re fit, they’re healthy—or at least they were until they’ve had these months of debilitating symptoms. And many of them are not reflected in case counts. They’re certainly not reflected in hospitalizations, in deaths, and in recoveries.

All these numbers that we use to tell the stories of the pandemic are missing out on a large number of people. And I think if we knew their stories, we might make a different calculus about our own risk. If you knew that a lot of young, healthy people would be sick for months, maybe eventually suffering from permanent disability as a result of this, maybe that’s going to change your view about whether we should be reopening or going back into the world. And I think that, as journalists, it is our responsibility to resist those easy dichotomies and to find all the missing nuance in the middle that is important, but is also being neglected.

In this period of social distancing, what have you been reading right now that’s either helping to provide some context around our current moment or providing distraction from it?

I wish I had more to say, honestly, but I have been working round the clock on pandemic coverage, and I’m finding it draining. I don’t really have a ton of mental capacity to concentrate on the kinds of fiction and nonfiction that I would normally be reading. Clearly, a ton of other people are undergoing far greater hardships, so I’m not really complaining. But for me, this is such a pivotal moment and it is so fast-moving, the stakes are so high, and the responsibilities are so great that it’s really consuming almost all of my attention and mental energy right now.

Send a message to The PEN Pod

We’d like to know what books you’re reading and how you’re staying connected in the literary community. Click here to leave a voicemail for us. Your message could end up on a future episode of this podcast!