There have been striking differences in how certain countries in Eurasia have responded to COVID-19 with regard to freedom of expression, access to information, and privacy rights. Authorities in some post-Soviet countries have shown a degree of responsibility with regard to safeguarding human rights, while others have used the public health crisis as cover to infringe on rights and persecute those who dare to speak out.

Below, an overview of how states across Eurasia are responding to the pandemic, up-to-date as of May 4:

Belarus: Government disinformation, action in hands of the people

Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko has called COVID-19 a “psychosis” and recommended people drink vodka, go to banyas (saunas), or work in the fields to ward off the virus. While the Belarusian government does not fully deny the existence of COVID-19, it has heavily downplayed its severity and failed to implement official information campaigns, profoundly endangering public health. Meanwhile, Belarus has one of the fastest growing infection rates in Europe. Lukashenko continues to state that no one would die from the virus itself, but from pre-existing illnesses.

Belarusian citizens, unwilling to accept the government’s irresponsible policies, have taken preventive measures themselves and introduced a “people’s quarantine.” Doctors have recorded videos encouraging citizens to stay home and follow medical requirements. Almost 50,000 people signed a petition to the World Health Organization demanding a mandatory quarantine. Belarusians have donated more than one million euros to purchase protective clothing for health workers and acquire coronavirus tests.

While it has promoted inaccurate information, the government has also gone after journalists and others attempting to tell the truth. Officials arrested Serguey Satsouk, director and editor of the news website Ezhednevnik, on charges of bribery and held him in detention for more than a week after reporting on and critiquing the government’s response to the pandemic. Prosecutors in the city of Vitebsk summoned Dr. Natalia Laryonava after she wrote on social media about her experience and called the authorities’ official numbers of COVID-19 cases “a complete myth.”

Georgia: Transparent government information and dismissal of TV journalists during state of emergency

After the confirmation of its first COVID-19 case at the end of February, the Georgian government began taking preventative measures: closing schools, kindergartens, and universities. The government set up a website providing safety recommendations and decoding myths on the spread of COVID-19. At first, the site was only available in Georgian, Armenian, and Azeri, but later information campaigns were launched in Abkhaz and Ossetian, recognizing the country’s linguistic diversity.

Due to an increased number of cases, the government declared a state of emergency from March 21 through April 21, and later prolonged it until May 22. Georgian law only allows a state of emergency to last six months. According to the Georgian Constitution, a state of emergency allows the government to restrict a number of constitutional rights, including rights to liberty, freedom of movement, privacy and private communication, free media, public information, and private property.

Under the state of emergency, the government has issued a curfew, prohibiting citizens from walking outside between 9pm and 6am, and a nationwide ban on driving private vehicles; the driving ban was lifted on April 27. Citizens who repeatedly break curfew can face up to three years in prison. The government also suspended its compliance with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) under article 15, which allows derogations and human rights restrictions in times of emergency; although some observers have noted this should not have a significant impact on a government’s obligations to respect its citizens’ rights. Courts in the country have been criticized for holding closed hearings. The Georgian Public Defender has also accused the publicly-funded Adjara Public Broadcaster, whose board of advisors has close ties to the government, of “violating labor rights” for dismissing journalists who have criticized the station’s new leadership and associated changes to the editorial policy.

The Georgian government’s response team, led by three health professionals, provided citizens transparent information on the risks and consequences of COVID-19, although the government has at times violated the rights of its citizens.

Russia: Cover-up of cases, crackdown on free expression, and threats to privacy

Initially, the Russian government reacted passively toward COVID-19, and for weeks failed to implement meaningful measures and widespread public information campaigns to prevent the virus’s spread. Government agencies initially reported a relatively low number of cases, but pneumonia-related incidents have risen, raising questions about the government’s official reporting.

Media outlets trying to investigate and expose the truth about COVID-19 cases in Russia are under serious pressure, facing accusations of “dissemination of false information” and of “sowing panic among the public and provoking public disturbance.” Roskomnadzor, Russia’s state media regulator, ordered radio station Ekho Moskvy and news site Govorit Magadan to remove articles about the COVID-19 outbreak and related deaths from their platforms. A number of journalists, such Tatyana Voltskaya, who writes for the RFE/RL-affiliated Sever.Realii website, and Lyudmila Savitskaya, have been questioned by law enforcement agencies over their reporting, and in some cases, have been asked to revoke articles or pressured to reveal sources.

In Chechnya, journalists at Novaya Gazeta were threatened by the head of the Chechen republic, Ramzan Kadyrov, after one of their journalists, Elena Milashina, published articles about the outbreak of the virus. Previously, assailants have assaulted and otherwise targeted Milashina for her reporting.

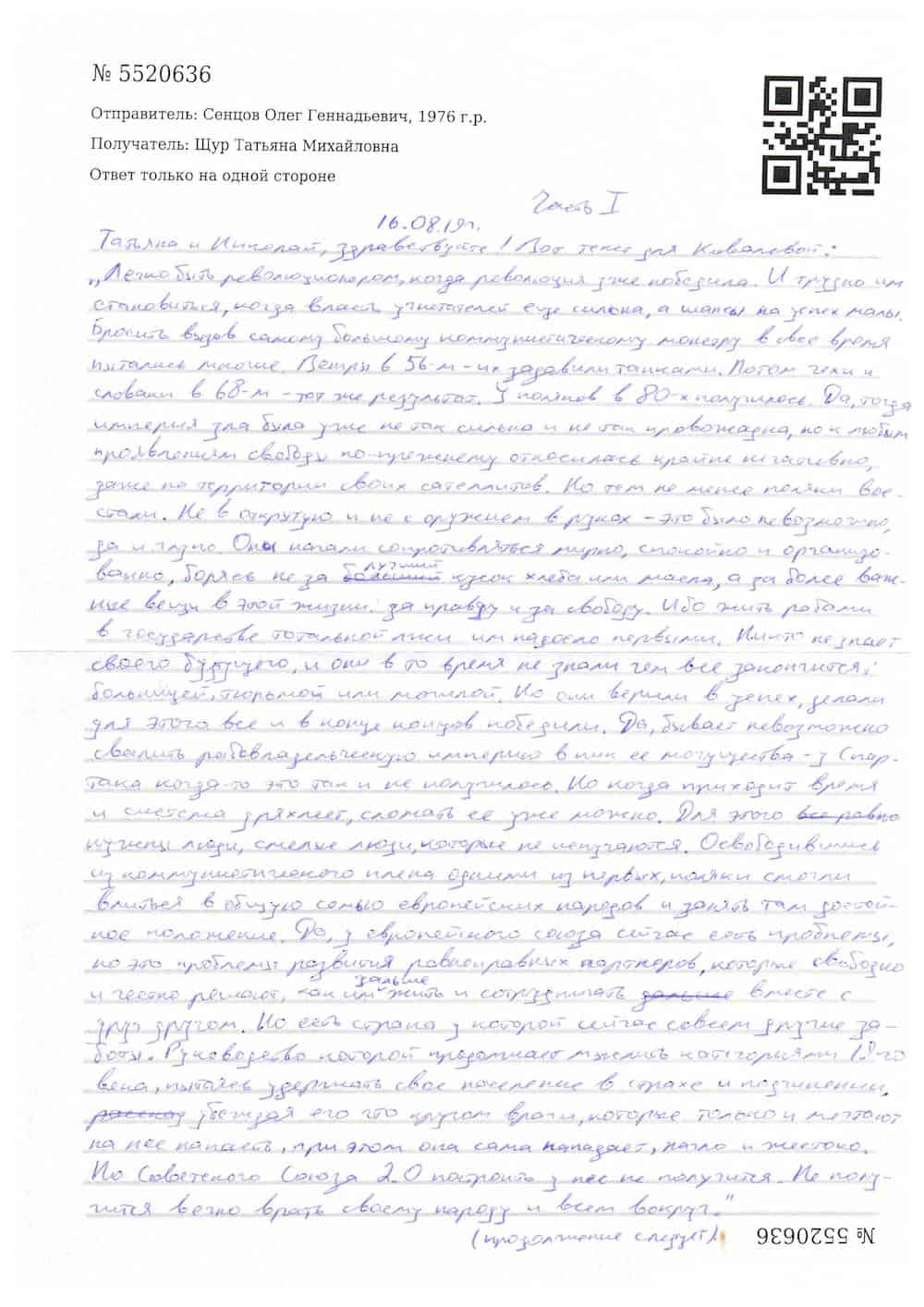

The government continues to prosecute writers, academics, and human rights activists for their work, allowing no reprieve for those who face serious health risks in Russian prisons. A court in Petrozavodsk extended the detention of historian and chairman of the Karelia branch of the Memorial Historical Society, Yuri Dmitriev. Dmitriev, 64, has worked for years uncovering mass graves of political prisoners executed under Stalin, drawing the ire of the Russian government. His lawyer now worries for his health in prison in the midst of the pandemic.

Even as Russian President Vladimir Putin’s government has downplayed the spread of the virus, it has introduced some surveillance measures that—while potentially useful for case tracking—raise concerns, especially in the hands of a government that retaliates against its critics. The use of a QR code to allow residents to leave their homes while in self-isolation enables authorities to track individuals’ locations, which could lead to privacy violations, and could potentially allow the government to track the whereabouts and contacts of dissidents. Additionally, government officials have introduced a video surveillance app, used for facial recognition, purportedly as a preventative measure.

At the same time, Putin has signed into law legislation establishing harsh punishments for those who spread false information about the epidemic. If people knowingly disseminate false information, they may face draconian fines or imprisonment for up to five years. Several criminal investigations have already been opened, including one against Anna Shuspanova, a St. Petersburg activist, who published a social media post about a person who was tested for the virus and then sent home from the hospital via public transportation. She later deleted the post.

Ukraine: Inefficient information campaigns on Kyiv-controlled territories and massive human rights violations in occupied regions

On March 3, the Ukrainian government launched a website about COVID-19 in Ukrainian and English, with regular information on case numbers, public restrictions, and medical institutions. Still, the government has been criticized for inefficient, confusing and uncoordinated information campaigns, which have made it more difficult for citizens to understand preventive measures. On March 25, the government declared a state of emergency and later extended it until May 12.

On April 29, Hromadske journalists Bohdan Kutiepov and Nikita Mekenzin were attacked by Ukrainian police while reporting on a demonstration of small business owners outside a government complex in Kyiv. Alla Zhiznevska from ZiK TV was interviewing demonstrators, asking them why they were ignoring lockdown restrictions, when they attacked her. Tetiana Sivokon from the TV channel NewsOne was attacked by a shop owner after asking him if his shop was holding protective medical masks as part of a story about mask shortages in Ukraine.

In the Russian-occupied Ukrainian regions of Donbas and Luhansk, the occupying authorities have tried to conceal facts of the spread of COVID-19. Officials have seized clinical records of the deceased, and authorities have threatened criminal prosecution for medical staff who disclose information. The occupying authorities in Donbas and Luhansk have closed their side of the crossing points to Kyiv-controlled areas.

In Russian-annexed Ukrainian Crimea, the lives of Ukrainian and Ukrainian Crimean Tatar political prisoners are at risk, as conditions in detention facilities worsen and medical help is absent. Crimean Tatar political prisoner Server Mustafayev, coordinator of the organization Crimean Solidarity, was denied access to medical care after having a high fever and showing symptoms of COVID-19. He said in a statement:

“I wrote a statement asking for a doctor to listen to my lungs. But I was taken to a video conference to participate in a court hearing, and I was never taken to see a doctor. I do not want to complain, but this is torture. In prison, a person simply does not have an opportunity to protect himself.”

Armenia: Hard line against media and doubtful surveillance measures

In Armenia, the government’s confrontational relationship with the media has persisted during the pandemic. The government has assembled a useful online portal providing information about government policy and updates on travel restrictions in Armenian, Russian, and English. But at the same time, the government has introduced questionable surveillance measures and increased pressure on the media.

The Armenian government declared a state of emergency on March 16, extended now through May 14 (some restrictions were eased on May 4). Like Georgia, it has also suspended compliance with article 15 of the ECHR, and initially instituted strong restrictions on the media’s ability to report on the outbreak, including forbidding them from citing non-governmental information sources and from publishing “reports that could cause panic among the population.” Under these guidelines, news outlets were regularly ordered to delete or edit articles. After domestic and international outcry, the government lifted these restrictions on April 13. Still, a provision remains, allowing fines if outlets refuse to delete banned content within 24 hours.

Meanwhile, a scandal erupted after a video of the Armenian prime minister leaked, showing him coughing and drinking water before delivering a speech on COVID-19. While innocuous, politicians close to the prime minister criticized the public television broadcaster. A group of high-ranking employees at the network resigned, and government officials said filming the prime minister without his knowledge posed “security risks.”

Finally, the Armenian parliament passed a controversial law giving it significant powers to use cell phone data to monitor the movements of citizens during the state of emergency. International and local human rights NGOs have raised concerns that the measures could be abused and require appropriate constraints to ensure they do not infringe on people’s rights.

***

Amid a global pandemic that puts every citizen’s health at risk, governments must walk a fine line, ensuring public health while also respecting human rights. Governments must implement politically and socially responsible policies that protect every citizen’s life; and while some restrictions on rights may be necessary to respond to this unprecedented threat, their potential for abuse must not be ignored. Such measures risk becoming difficult to reverse once they are in place.

Transparency is critical, and safeguards are necessary to ensure temporary restrictions do not become permanent infringements on rights. In such contexts, the role of journalists in investigating, reporting, and holding government to account only becomes more critical. Across the region, it is also urgent that writers, academics, activists, and journalists held unjustly in prison be released, lest they face unnecessary risks to their health, in addition to existing infringements on their rights.