This essay is part of PEN America’s We Will Emerge project, a collection of essays speaking directly to voters around the country in advance of the U.S. election. This project is made possible with the support of Pop Culture Collaborative’s Becoming America Fund.

LISTEN TO LAILA LALAMI READ HER ESSAY

“Terrible voting weather,” a character remarks at the beginning of José Saramago’s Seeing. In this powerful novel, torrential rains blanket the streets of an unnamed capital and no one turns up to vote until late in the afternoon. When the ballots are counted, however, poll workers discover that more than 70 percent of them are blank. The few valid ballots aren’t enough to give complete legitimacy to the winning party, which is the party on the right. (The other parties—the party on the left and the party in the middle—earn humiliatingly small percentages of the vote.) After a period of confusion, the government organizes a new plebiscite, in the hope that citizens will exercise their civic duty and cast proper ballots. But the number of blank ballots this time is 83 percent, thrusting the capital into bureaucratic disarray, media excitement, and government conspiracy.

I read Seeing years ago, during a period of time in which I devoured Saramago’s books one after the next, barely pausing to catch my breath. I was reminded of it recently because of what it has to say about the current moment. The novel renders as literal fact the situation we have in the United States, where turnout in the last presidential election was little more than half of all eligible voters. In effect, more Americans sat out the election than voted for the current president. “I don’t feel bad,” one nonvoter from Wisconsin told The New York Times in November 2016. “They never do anything for us anyway.”

I recognize this feeling, because I grew up hearing it. Perhaps you heard it, too, from people in your life who speak of elections with indifference or even distrust. After all, elected leaders change, but images of police brutality, border violence, and drone bombing continue to flicker on our screens, year in and year out. It’s hard for conditional citizens—people whose rights are often curtailed because of accidents of birth, like race, gender, or class—to trust in a system that historically has not served their interests. To add insult to injury, conditional citizens may be courted during electoral campaigns, then ignored the rest of the time.

But the disproportionate focus on presidential politics in our media obscures the fact that elections are about local choices as well. We choose sheriffs, district attorneys, state and local judges, and school board members, which is to say the people who will make decisions that directly affect how criminal justice is handled in our communities, how schools are run in our districts, or what textbooks are chosen for our children. Not voting means forfeiting the right to have a voice in policy decisions that affect us every day in concrete ways. The government isn’t just in the White House; it’s here in our streets, and the ballot is the only means we have to evaluate the public servants whose salaries we all pay, whether we choose to vote or not.

“The government isn’t just in the White House; it’s here in our streets, and the ballot is the only means we have to evaluate the public servants whose salaries we all pay, whether we choose to vote or not.”

Then there are state propositions on the ballot. In California, where I live, voters can decide by simple referendum whether people who have served their felony convictions should regain voting rights, whether rent control should be expanded by local governments, and whether cash bail should be replaced by risk assessment for suspects in pretrial detention. In other words, we have in our hands the power to expand the franchise, protect people from eviction at a time of enormous financial strain, or reduce the number of people in pretrial detention. In each case, the lives of tens of thousands of people—our families, our friends, our neighbors—will be affected by the outcome, whatever it may be.

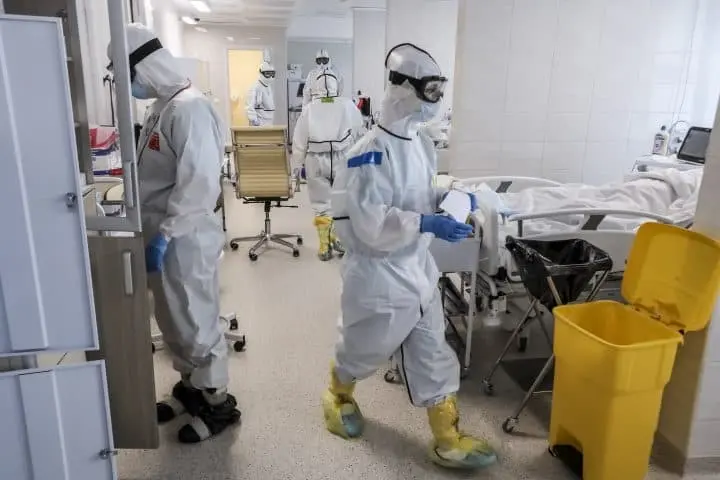

Of course, nonvoters aren’t the only reason why turnout in U.S. elections remains relatively low compared to other democracies. There are millions of would-be voters who face obstacles of all kinds, resulting in disenfranchisement. In some states, particularly in the Deep South, many polling stations have been closed, which means lines of as long as 12 hours for casting a ballot. Hourly-wage and other nonexempt workers must forfeit a day’s pay in order to take part in the electoral process, at a time when the pandemic has already caused a lot of financial stress for so many people.

There are also rules that complicate the voting process unnecessarily. Some states have plenty of collection boxes for mail-in ballots, for example, while others limit them to one per county. Then there are logistical hurdles. Once, I remember, I was text banking with voters in Georgia to remind them to vote when I heard back from an elderly lady who said she lived in a rural area and didn’t have a ride to the polls. Each year, voters like her are prevented from participating in the democratic process because voting is more onerous and more convoluted than it needs to be.

To me, the most important reason for voting has to do with our past and our future. In the earliest days of the republic, the franchise was a privilege accorded only to propertied white men. They could be governed by consent, but everyone else was to be governed by force. It took decades of struggle, some of it violent and bloody, for voting rights to be extended to people of other races and genders. Until the Civil Rights Act, the right to vote could not be taken for granted: Black people were enfranchised, disenfranchised, and reenfranchised depending on the state and the political moment. Given this history, voting is a moral obligation, a way to honor the sacrifices of the people who came before us.

It is also a way to honor those who will come after us. In the last few weeks, California has been consumed by the largest wildfires in the state’s history, which have severely damaged our air quality and threatened the health of our most vulnerable residents. Elsewhere in the United States, there have been massive tornadoes in Iowa, record-shattering heat waves in Florida, and hurricanes in Texas. Casting a vote with the future in mind is a way to take responsibility for the kind of natural environment we will leave for our children.

“Despair won’t fix this mess; only action will. What is certain is that the struggle is collective and our success will depend on solidarity.”

Earlier this month, I spent time researching the candidates and initiatives on the ballot, then filled it out and mailed it. Afterward, I took a walk through our neighborhood, where signs advocated for different candidates for school board, city council, or president. One of my neighbors, fed up with the abundant advertising all along our tree-lined street, recently put up a sign that read “Giant Meteor 2020.” I let out a dry laugh. Our state is struggling with wildfires, a housing crisis, food insecurity, and the effects of the coronavirus pandemic—a meteor can’t be much worse.

Yet the sign also signaled despair, which is a gift to apathy. Apathy isn’t going to resolve the crisis we face. Since March, the United States has endured a public health emergency and an economic downturn that have been called “unprecedented.” No one can say with certainty how much time it will take to develop a vaccine against COVID-19, how long schools and businesses will remain closed, and whether workers will recover from the loss of jobs and wages. Despair won’t fix this mess; only action will. What is certain is that the struggle is collective and our success will depend on solidarity.

Active solidarity takes many forms. We can join local mutual-aid organizations, make monthly contributions to food banks, volunteer in schools, or donate time, money, or effort to various grassroots organizations. We can strike, protest, or engage in acts of civil disobedience. Voting is another expression of solidarity, especially when our electoral choices are based not just on self-interest, but on collective well-being.

Those of us who have the right to vote have a huge responsibility toward those who don’t, including children and young adults, documented or undocumented immigrants, incarcerated or formerly incarcerated people, and citizens who can’t access the ballot for various reasons. Voting is our duty in the social contract, a way to steer the republic in a direction that accurately reflects the will of all its citizens.

In Seeing, the blank ballots create a dilemma for the government and the media because they deprive the former of legitimacy and the latter of a conventional story. But the fallout is swift. The minister of defense imposes a state of emergency, which is breathlessly but unquestioningly covered by journalists. The people seemed unmoved, however. They go on about their daily business. “Since the citizens of this country were not in the healthy habit of demanding proper enforcement of the rights bestowed on them by the constitution,” Saramago writes, “it was only logical, even natural, that they failed even to notice that those rights had been suspended.” These words serve as a warning, which we should heed, now more than ever.

Laila Lalami was born in Rabat and educated in Morocco, Great Britain, and the United States. She is the author of four novels, including The Moor’s Account, which won the American Book Award, the Arab-American Book Award, and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction. Her most recent novel, The Other Americans, was a national bestseller and a finalist for the Kirkus Prize and the National Book Award in Fiction. Her essays and criticism have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, The Nation, Harper’s, The Guardian, and The New York Times. She has received fellowships from the British Council, the Fulbright Program, and the Guggenheim Foundation and is currently a full professor of creative writing at the University of California at Riverside. She lives in Los Angeles. Her new book, a work of nonfiction called Conditional Citizens, was published by Pantheon in September 2020.

Laila Lalami was born in Rabat and educated in Morocco, Great Britain, and the United States. She is the author of four novels, including The Moor’s Account, which won the American Book Award, the Arab-American Book Award, and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction. Her most recent novel, The Other Americans, was a national bestseller and a finalist for the Kirkus Prize and the National Book Award in Fiction. Her essays and criticism have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, The Nation, Harper’s, The Guardian, and The New York Times. She has received fellowships from the British Council, the Fulbright Program, and the Guggenheim Foundation and is currently a full professor of creative writing at the University of California at Riverside. She lives in Los Angeles. Her new book, a work of nonfiction called Conditional Citizens, was published by Pantheon in September 2020.