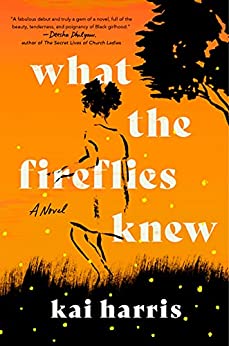

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Kai Harris, author of What the Fireflies Knew (Tiny Reparations Books, 2022) – Amazon, Bookshop.

1. What is your relationship to place and story? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

I don’t necessarily return to specific places, but I’ve discovered that I like to put my characters in places where I’ve spent time. This gives me the opportunity to be in those places again, but through the eyes of my characters. My debut novel, What the Fireflies Knew is set in Lansing, MI, where I once spent summers as a child. As soon as I picked up my pen to write about this place, I could see it and smell it and hear it. That’s the magic of place, and why it is one of the most important aspects of a story. It’s where the story happens, and it gives us context for everything we experience there. When these places are real and raw and visceral, this is how stories transport us somewhere new—whether that’s somewhere familiar, or somewhere we’ve never been before.

2. Writing is often a private and intimate process. On February 1, What the Fireflies Knew will also belong to readers. How do you prepare for that?

I don’t think it’s possible to be fully prepared! I’ve spent a lot of time thinking through where I want to be mentally when the book is out in the world, and figuring out how to stay in that state of mind. I want to be calm and confident in knowing that I wrote a book that I feel is important for the world to read. What happens from there is outside of my control, so I’m learning to go with the flow.

“I often think to myself: maybe something I write will change the world. Or maybe something I write will change the world for just one person. Either way, I have to try.”

3. What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing your book?

I think the most surprising thing was that I could do it. I could write a book based on the experiences of a young Black girl and people would not only care to read it, but love it.

4. What the Fireflies Knew is told from the perspective of KB, a young Black girl coming of age in 1990s Michigan. While adjusting to seismic shifts and losses in her home life, she also learns quite a bit about herself and the family secrets that had been fiercely guarded before her father’s sudden death. Did writing from KB’s point of view remind you of anything surprising about the vantage point of children that you might’ve forgotten in adulthood?

Writing from KB’s vantage point taught me a lot. It was eye opening to consider what KB would know and understand about the world around her. Even though she is young, she is very curious and smart and asks a ton of questions. Sometimes the reader will know more than KB, but she’s usually not too far behind. And this is important because all too often, adults forget that kids are experiencing the world, too. We expect them to be quiet and stay out of sight. We don’t respect or acknowledge the trauma they experience. But they’re right there, seeing and hearing and living everything. When we don’t give them space to process, to ask questions, to be honest—we don’t give them the tools they need to heal. KB reminded me of just how important this is.

5. What’s something about your writing habits that has changed over time?

I’d say that I’ve gotten much more efficient at it—thankfully! At the start of the pandemic, when writing was even more challenging than usual, I spent a good deal of time observing and studying what works well for me when writing. I kept a journal and for every writing session, I would take inventory of what I was doing and how well it worked. For example, I’d note what time of day it was, where I was sitting, what I could hear, etc. Then I would rate how well the writing session went. Did I have any breakthroughs, did I write a ton, did I feel accomplished? For all the days when my writing sessions went well, I highlighted what I was doing during those sessions. From there, I started to build all my writing sessions around those things that make me more creative and productive.

6. What is a moment of frustration that you’ve encountered in the writing process and how did you overcome it?

6. What is a moment of frustration that you’ve encountered in the writing process and how did you overcome it?

The first time I had to really revise Fireflies… that was pretty frustrating. At the time, I thought I knew how to revise, but it turns out I was mostly inefficient. I had never had to do such a large-scale revision with so many sources of feedback to consider. At first, it was overwhelming. Then I took a step back and did what I always do: I spent time figuring out what would work best for me. In the end, I downloaded some tools, built a couple spreadsheets, and filled my writing space with colorful index cards covered in plot points and character arcs. When I began revising my second novel, I noticed that the process was much easier because I had built a system and flow that works well for me.

7. What advice would you give to a writer who is trying to publish their book—not just in general, but especially in this current climate?

My advice would be to just tell your story. Write the story, get it down on the page. Nothing else can happen until that happens. While you are doing that, read everything you can read and connect with as many folks as you can. Then, when it comes time to put your story into the world, fight as hard as you can to stay true to the thing that made you write it in the first place.

8. What is the role of a writer in an era of social unrest? Polarization? Democracy in decline?

As Toni Morrison once said, “It [writing] is a dangerous pursuit….But it’s one of the most important things that human beings do.” I believe the role of a writer in an era of social unrest is to be honest. To write the truth that the world needs to hear. We can’t fix everything with our words, nor should we be expected to. Yet, there is a power in our words that we shouldn’t shy away from. I often think to myself: maybe something I write will change the world. Or maybe something I write will change the world for just one person. Either way, I have to try.

“I believe the role of a writer in an era of social unrest is to be honest.”

9. What is one critique of your work that you have really learned from?

Back when I was getting my MA, I started writing a novel. It was about a middle-aged white man who was a scientist and decided to test his theory of love. While maybe an interesting concept, the book itself was pretty bad. I didn’t know anything about this character because I knew nothing about the life I was trying to give him. As cliché as it is, the most important critique of my work was to write what I know. But not so much writing my own story; more so writing from my own identity, in my own voice. I used to think I had to write about certain kinds of characters and experiences for my writing to be taken seriously. Now, the most important thing to me is to write from my experience, unfiltered stories of Black girlhood and womanhood told in authentic voices. Whether it’s taken seriously or not, this is what I choose to write about.

10. In addition to writing you’re also a professor of creative writing. What’s a lesson—craft related or not—that you always try to impart on to your students?

Figure out what works well for you and do that! You could get advice from 100 different writers and probably end up with 100 different strategies or tips on how to write. And maybe 99 of those things won’t work for you. You have to find the one that will. In my classroom, we experiment a ton. I ask my students to keep a journal where they work to discover what fuels their creativity and what enhances their writing process. If I say anything in class that doesn’t vibe with what they are discovering about themselves, then I tell them to ignore me completely. Ultimately, it’s all about figuring out what makes you most creative, most productive, and most at home in your creative process.

Kai Harris is a writer and educator from Detroit, Michigan, who uses her voice to uplift the Black community through realistic fiction centered on the Black experience. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Kweli Journal, Longform, and the Killens Review, amongst others. In addition to fiction, Kai has published poetry, personal essays, and peer-reviewed academic articles on topics related to Black girlhood and womanhood, the slave narrative genre, motherhood, and Black identity. A graduate of Western Michigan University’s PhD program, Kai was the recipient of the university’s Gwen Frostic Creative Writing Award in Fiction for her short story, “While We Live.” Kai now lives in the Bay Area with her husband, three daughters, and dog Tabasco, where she is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Santa Clara University. Follow Kai on Twitter @authorkaiharris for a healthy dose of #blackgirlmagic. Read more at kaiharriswrites.com.