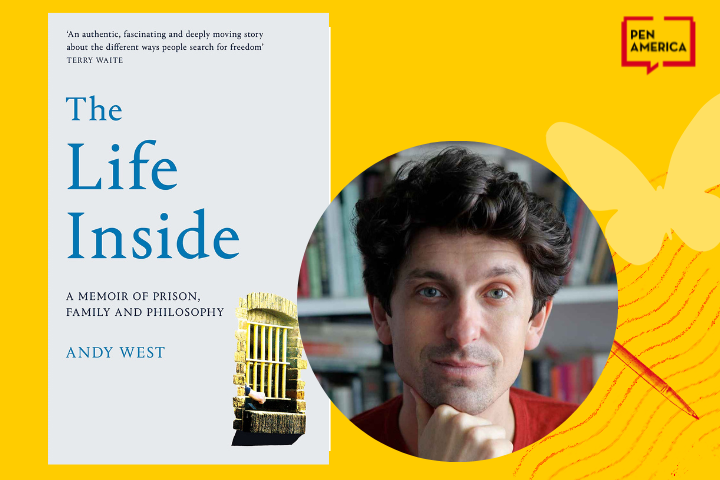

The divides marked by prison walls—between criminal and not, flat assumptions of “good” and “bad,” freedom and captivity—become entrenched in the psyche of people who live within the harsh realities of the justice system daily. For Andy West, this division is all too palpable in the “inherited guilt” he feels as a result of growing up with an uncle, a brother, and an estranged father’s frequent stays in prison. In The Life Inside: A Memoir of Prison, Family and Philosophy (Picador, 2022), West reckons with the psychic impact of the carceral system through a narrative account of philosophy lessons he developed for prisons throughout the United Kingdom.

The memoir is organized into chapters titled for philosophical subjects, all of them the central themes for West’s classes. As he recounts these lessons, West recalls those he learned as a child who regularly witnessed the workings of the justice system through the policing and incarceration of the men in his family. In the chapter titled, “Shame,” the author describes accompanying his father through these series of moves between his stints in prison and an accompanying set of fake names, resulting in a longstanding fear that friends would find out who he really was and abandon him. As if his father’s false identities had been passed down to him, West develops “an executioner in [his] head,” looming with the constant thought that his father’s cycle of crime and incarceration would eventually befall him as well. Teaching in prison brings West face to face with the very site of his fears, affording him the opportunity to process his experiences through the perspectives of his students.

In the lesson on “Trust,” West uses the story of a scorpion and a frog to discuss the pros and cons of putting confidence in others. The scorpion convinces the frog to let him ride on his back across the river — only to sting the frog halfway through, drowning them both. After reading the story, West’s students reach near consensus that the frog is an idiot. One student paraphrases the majority opinion: “The whole moral of the story is kindness has no place in nature.” Through this example, West highlights the punitive thinking internalized by several of his students, who believe the crimes they committed makes them a different ‘species’ endemic to a prison environment, that the only way to survive inside is to be the scorpion. For his students, everyone is a potential threat, and trust is a scarce luxury. Their cynicism echoes West’s own anxiety that criminality could actually be in his ‘nature,’ woven into his genetics.

For the lesson on “Luck,” West imagines two worlds, one where all the events of a person’s life are based on chance, and another where they are based on choice. One student argues reality is more like that latter: “I’m in prison because I made a choice…It’s easier to say you’ve been unlucky than to face up to your own immaturity.” The student’s self-condemnation uses incarceration as a sign of personal character, “I’m thirty fucking years old and I still haven’t grown up.” West relates to the student’s identification, perspective. Growing up with his older brother in and out of prison, West was tormented by the thought that it was only luck that helped him avoid prison.

Visiting prison as a teacher, West encounters many reminders of his traumatic childhood and works through his hovering dread. By learning the signs of his mental executioner, West is able to stop indulging his guilt by directing attention away from his triggers. As he writes in the chapter on change: “I feel like I have just done something audacious. I didn’t show up to my own execution.” Studying alongside his students who are incarcerated allows West to see how prison has shaped his own psyche, giving him the confidence to turn away from his self-incriminating thought patterns.

Ultimately, the strength of West’s storytelling lies in this personal narrative, following his growth through his return to the origins of his anxieties in childhood to finally learning to come to terms with his past through his experience teaching in prison. Across the diverse lessons, gleaned in class settings and personal conversations, West lays a blueprint for how to cope with the harsh and imposing logic of the justice system. By attending to the humanity of his students, West is finally able to accept his own, reaching across the false divisions the prison system puts between them.

Sophia Ramirez talks with Andy West Keeda J. Haynes about incarceration in the UK, what led him to write a memoir, and his approach to writing about and for people who are incarcerated on PEN America’s Works of Justice podcast.

Tomás Miriti Pacheco is a poet and journalist from Columbus, Ohio.