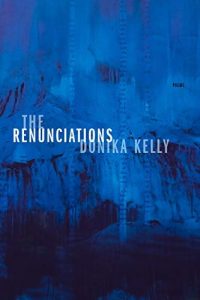

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Gabriel Fine speaks with Donika Kelly, author of The Renunciations (Graywolf Press, 2021).

1. In your poem “Hymn,” you write, “The closer I am / to my animal self the more human I am.” Animals feature frequently in your poems, both in The Renunciations and, of course, your debut collection Bestiary, often as a site or vehicle for some sort of transformation. What do you find compelling about the animal or natural world?

What I find most compelling about the animal and natural world is that the motives of those lives—animal lives, plant lives, mineral, and stone—those motives exist outside the human framework. There is no regard for our values, our philosophical dilemmas, or the structures we enable that cause harm. Understanding that we are not the center of any world other than our species’ own gives me small hope about other ways of being and knowing that prioritize balance over dominion. Most personally, though, situating my hurts, which feel so big inside my body, against the natural world scales my feelings to my own singular smallness and makes them more manageable.

2. Many of the poems in The Renunciations employ a kind of erasure or omission, with some lines redacted and others left blank. What drew you to employ these techniques, and what role do you think elision plays in the collection?

In one way, the twinned strategies of erasure and redaction in this collection are meant to remind the reader that they do not have access to everything. They signal that the speaker is withholding information, that there are things she is choosing not to say. The erasure, the bracketed space, also serves as a kindness to my speaker, a small relief from disclosure.

“Poetry can shine a light on the lived realities of harmful social and political dynamics…but poetry alone can’t change them. What poetry does is reassure folks they aren’t alone in that reality—that there is community, and through community effort, there can be change.”

3. The Renunciations asks many difficult questions about trauma: How do we remember our wounds, reckon with them, renounce them, transmute them? Do you feel like poetry is or can be a vehicle to work through trauma, both personally and politically?

I do, yes, but I suspect there are limits. Poetry has been a big part of the process of moving through a traumatic history, and I’ve ended up on the other side with a deeper understanding of that history and my role inside it. But the history is still there. It’s still mine. I still have to carry it. There’s a similarly circular dynamic, politically, as well. Poetry can shine a light on the lived realities of harmful social and political dynamics, for example, but poetry alone can’t change them. What poetry does is reassure folks they aren’t alone in that reality—that there is community, and through community effort, there can be change.

4. In an interview with Nikki Finney, you described poems as “a gesture fixed in time”—that is, as an object made during and of a certain moment that nevertheless may change in meaning as the writer changes. As a poet who is now releasing your second collection, has your relationship to your own writing and language changed? Did the creative process of writing The Renunciations alter your perception of your own language or the writing you had created up to that point?

After Bestiary, I needed to figure out how to practice vulnerability without the thick mask of persona. I wanted to write poems that could sing, yes, but that were also clear in both diction and sense. I wanted the speaker to be a person and not, say, a minotaur. Clarity is vulnerable. Plain speech can be vulnerable. I think I got there with these poems. This book is a tender thing.

5. What do you read (or not read) when you’re writing?

My reading habits don’t change when I’m writing, probably because I write in brief spurts. I’m a re-reader. I revisit novels and poetry collections I have loved, sometimes to see if I still love them, but often to find what’s new in them—which is another way of thinking about how I’ve changed since I last read a particular book. This is as true for literary novels and poetry collections as it is for romance novels and children’s books.

“Clarity is vulnerable. Plain speech can be vulnerable. I think I got there with these poems. This book is a tender thing.”

6. The Renunciations is, among many things, a collection about love––its precariousness, its failures, but also its joys. Are there any things in your life today––people, places, books, albums––that you love or that make you feel loved, that offer you solace and joy?

I am, gratefully, well-loved. From my partner, to my friends, to my sister and grandpa, I feel held and get to practice holding onto them, holding space for them, though most of us haven’t seen each other in over a year. The first album that came to mind is Fiona Apple’s third album, The Idler Wheel Is Wiser Than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Cords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do, which has gotten me through a lot, especially the song, “Largo.” Brittany Howard’s voice, particularly on “This Feeling,” and Roberta Flack’s “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” tap into deep wells of good feeling.

7. Several poems in The Renunciations feature the speaker in dialogue with the Oracle of Delphi, an ancient Greek prophet. Do you think poetry can help envision the future, either in your own life or in the world at large? Especially during the pandemic, it seems like we’re doing so much looking forward, as are the speakers in The Renunciations. What do you think is the relationship between poetry and prophecy, between writing and seeing?

7. Several poems in The Renunciations feature the speaker in dialogue with the Oracle of Delphi, an ancient Greek prophet. Do you think poetry can help envision the future, either in your own life or in the world at large? Especially during the pandemic, it seems like we’re doing so much looking forward, as are the speakers in The Renunciations. What do you think is the relationship between poetry and prophecy, between writing and seeing?

Poetry is my primary tool of investigation and imagination. The oracle in the book is looking at the past, suggesting that some things are inevitable. Held inside the construct of the oracle is an idea that at one point, the oracle foretold what came to pass. Now I can’t really conceptualize the future, but I can investigate time, the past, in order to understand what has already happened, note the patterns, and my role in the events. From that understanding, I can try to imagine a different future, a future where it’s possible to make different choices. If I can imagine the future, then write it, that future becomes more possible to live in.

8. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

My poems come out of my experience, my understanding of the world. My experiences are shaped by my identity as a Black lesbian for sure, and also by my affiliate connections—to family, to friends, to students, and to colleagues. My poems are always Black, always queer, and always situated within a larger frame of connection.

“Now I can’t really conceptualize the future, but I can investigate time, the past, in order to understand what has already happened, note the patterns, and my role in the events. From that understanding, I can try to imagine a different future, a future where it’s possible to make different choices. If I can imagine the future, then write it, that future becomes more possible to live in.”

9. The geography of The Renunciations is wide-ranging and yet deeply intimate. What is your relationship to place, and how does sense of place figure in your poetry?

I have felt out of place my entire adult life, that there is no place that is mine to call home. My home is with my people, and the landscape, city or country, timber or high desert is a space to be grateful for. In a way, I remember the particularities myself—my relationship to my body, my evolving practices of vulnerability and boundary making—in relationship to where I have lived, which comes through the poems.

10. Which writers today are you most excited by?

I’m excited to get into my summer reading, which includes torrin a. greathouse’s Wound from the Mouth of a Wound, Diamond Forde’s Mother Body, Kayleb Rae Candrilli’s Water I Won’t Touch, and Roy G. Guzman’s Catrachos.

Donika Kelly is the author of The Renunciations and Bestiary, winner of the 2015 Cave Canem Poetry Prize, the 2017 Hurston/Wright Award for poetry, and the 2018 Kate Tufts Discovery Award. She teaches at the University of Iowa.