Deena Mohamed drew profound inspiration from a seemingly mundane place: kiosks.

In her latest graphic novel, Shubeik Lubeik, the Egypytian graphic novelist envisions a world where wishes are bought and sold. Her alternate world reflects on human desire, capitalism, grief and mental health.

Mohamed began making comics at 18 with her viral webcomic Qahera, a satirical superhero strip starring a visibly Muslim superheroine. For this week’s PEN Ten, she spoke with Sabir Sultan, World Voices Festival and Literary Programs Associate Director, about Shubeik Lubeik (Pantheon, 2023). Amazon, Bookshop

1. Shubeik Lubeik exists in an alternate universe where wishes are commodified and the strength of a wish is directly tied into its monetary value (i.e. the most powerful wishes–first class wishes) are the most expensive. The cheapest wishes–third class wishes–are the least powerful and prone to causing mishaps. What was the source of inspiration for the idea of buying and selling wishes?

Shubeik Lubeik was inspired by Egyptian kiosks. I’ve always had a long-time appreciation for them as colorful oases in the urban sprawl of Cairo, but they’re only so colorful because of all the brands and products they have. I thought of a kiosk that sold a magical object, and once I decided it was a wish I considered what a world where you could buy a wish at a kiosk would look like. Once you create a world where wishes are classified according to affordability (which is more or less the world we live in now) you consider what the real price of building a system like that would be, and how people would navigate it.

2. The world-building throughout the graphic novel is wonderfully complex. The location of wish mines (wish extraction zones) are consolidated in places like the Middle East, North and East Africa, and other regions in the global South, while the factories that refine and sell wishes are mostly located in western countries such as the US. This in effect creates a colonial/capitalist infrastructure where countries’ resources are mined and sold back to them. How did you approach recreating colonialist practices and a history of colonialism around wishes in your alternate world?

To me, the function of speculative fiction and magical realism, the joy of inserting fantasy in mundane urban reality, is to consider the implications of how it might function in our world. And so for Shubeik Lubeik, which is all about commodifying wants and needs, it was not really so far off that I needed to change most of the existing history we have. It felt right to have this alternate world feel familiar. Honestly, I don’t really know how I could have written it without this history. It just made sense.

“Once you create a world where wishes are classified according to affordability (which is more or less the world we live in now) you consider what the real price of building a system like that would be, and how people would navigate it.”

3. Time operates in fascinating ways in Shubeik Lubeik. The graphic novel was originally written in three books, each following a main character as they seek or use first class wishes to obtain their heart’s desires. Aziza, a widow, is the subject of the first book. Nour, a college student battling depression, is the subject of the second. Hagga, the neighborhood matriarch, is the subject of the third. Aziza and Nour’s sections happen almost concurrently, with events in each of their stories happening at different points in the other’s. Meanwhile, Hagga’s story involves two different timelines. How did you approach time in crafting the books? Did your approach to it change as you wrote subsequent books?

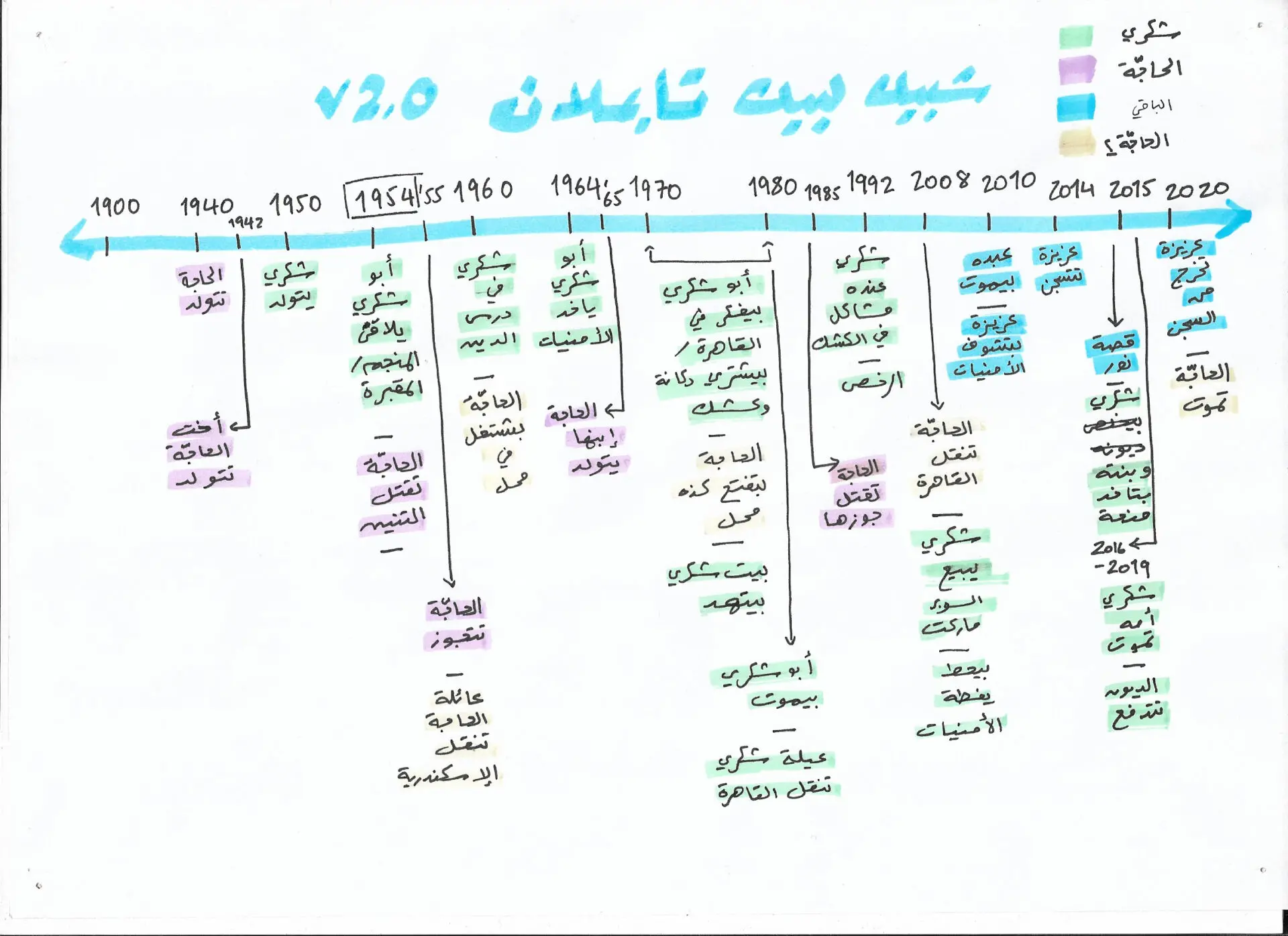

I actually had a fairly straightforward timeline! [The timeline] is in Arabic unfortunately and a few details would change in it, but you can see the green is meant to indicate Shokry’s life, the purple is Shawqia’s first life and the yellow is her second, while the blue is for everyone else. I knew Aziza and Nour’s stories ran parallel to one another, while Shokry’s would take place a few years later. I wanted the stories to interlock briefly, but still work as individual stories. [The timeline] didn’t really change because from the very beginning I had an outline for the ending, which is why the story begins with Shawqia coughing, as I knew the last wish would be about her.

4. Aziza works for four years to earn enough money to buy her wish. It is understood that the wish relates to the loss of her husband. In Hagga’s story, we also see her navigating grief. What did you want to explore with wishes born of grief?

When I first decided the story would be about wishes, I considered when people would want wishes the most. I think of wishes along the same lines of prayers, and people pray most desperately in times of loss and grief. I knew I couldn’t have a book about wishes without thinking about grief. Many stories about wishes have revolved around love, and grief is a very important form of love to me.

5. Some of my favorite images in the book come from Nour’s section. Nour creates graphs and charts to track the progression of his depression. We see his graphs illustrated on the page, and in other panels in the section, you play with the design features of graphs and charts. How did you approach incorporating those design features into your artwork and storytelling?

One of the principal elements of the stories is that I wanted them to be constructed a little bit like traditional fairy tales, where you follow a protagonist in a story within a story on their journey. These stories tend to be told a little bit at arm’s length; it’s a small window into a character’s life in the time between buying a wish and making a wish. It’s intimate but also isn’t. For Nour, the graphs were a good way to visually describe the state [he] is in, since the journey is mental and not physical. [The graphs were] also impersonal, and so keep the reader aware of Nour’s state of mind without sinking too deeply into constant monologues or dark imagery–[this helps to maintain] this sort of balance between intimacy and distance. [Graphs] also reflected the character itself; Nour used to love maths, was an honor roll student, and has a tendency to intellectualize and analyze their own state of mind. I also wanted to avoid the more conventional portrayals of depression as a “personified” monster of some kind, and focus on the general numbness of the depressive state instead, as it suited Nour’s specific experience more.

“I think of wishes along the same lines of prayers, and people pray most desperately in times of loss and grief. I knew I couldn’t have a book about wishes without thinking about grief. Many stories about wishes have revolved around love, and grief is a very important form of love to me.“

6. Nour seeks therapeutic help for how to use his wish to cure his depression. In several scenes, we see him undergo therapy. Given the complex nature of mental health, wishes have to be used carefully in conjunction with therapy to be effective cures. Was it important to you to show the value of therapy?

Most of my characters go through quite singular journeys, sharing their burdens with no one. In the story, Nour doesn’t have a confidante or really talk about their situation to anyone else, because the mental illness experience in Egypt can be very lonely. I think I couldn’t avoid the feeling of knowing that someone reading this story might be in a similar situation and looking for ways to help themselves, so I actually felt like it was more important to show the difficulty of therapy. I wanted the therapy portrayal to be unromantic and not particularly encouraging, especially at first. Therapy is expensive and hard to seek and doesn’t work for everyone, but why it matters is because it’s a decision to help yourself. You can make that decision in many ways, but the important thing is to make it.

7. Another main character in the book is Shokry, the street vendor who sells the first class wishes to Aziza and Nour. Shokry is also friends with Hagga. Shokry refuses to use the wishes himself as he believes the use of wishes to be haram, a violation of his faith. What is the relationship between faith and wishes in Shubeik Lubeik?

I just feel like world-building without considering religion as a necessary part of this world is always lacking. It was natural to include religion in the story because religion is an overwhelmingly present aspect of daily life, and this alternate universe would have to be VERY different to ours if religion did not exist. As I mentioned, I also conceptualize wishes as prayer, so it felt impossible not to address faith in a story about wishes.

8. If you could buy your own first-class wish, what would you wish for?

This was one of my favorite questions to ask people when I was writing this book! It was always very enlightening. Actually, like Shawqia, I would save my wish for emergencies. In case it wasn’t obvious from the stories, I enjoy worrying.

“Who has the right to approve and deny a wish? Who has the right to know people’s most intimate desires? … Everyone has the basic right to make a wish that does not impede on the rights of others, and so everything preventing that is a transgression.”

9. While there are fantastic elements in the book – dragons, a talking donkey, etc. – those elements are all born of wishes and based in human desires. We see characters wish for everything from the frivolous (cars), to the meaningful, (a cure for someone with cancer). Are there good wishes and bad wishes in your world? How do you value someone’s desire?

Certainly, there are. The idea of a regulatory body for wishes is to prevent malicious or evil wishes, but obviously with enough wealth you could get away with just about anything. It feels like an overwhelming concept to consider until you realize our world already works this way. But one of the important themes of Part 1 is interrogating the idea of who deserves to want what—people saw Aziza’s wish as frivolous and worthless, and yet in Part 2 we encounter someone who HAS wished for a car with no consequences. There is also the question of privacy: did Aziza need to disclose her wish at all? At the end of the book, a new law comes out that states every single wish must be declared, even immaterial ones. Who has the right to approve and deny a wish? Who has the right to know people’s most intimate desires? I don’t really have an answer for this, but I felt like it was an important starting point to establish that everyone has the basic right to make a wish that does not impede on the rights of others, and so everything preventing that is a transgression.

10. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I recently reread If An Egyptian Cannot Speak English, which I loved. I think I’ll be reading [Mohammed] Shennawy’s new comic, Feesh w Tashbeeh, which is a great comedic exploration of bureaucracy. The description on Cairopolitan’s website is in Arabic, but feesh w tashbeeh (فيش وتشبيه) refers to a document Egyptians often need to get for paperwork to travel or work, and involves your criminal record and fingerprints that need to get stamped by many different officials. It’s a silent comic about a little fingerprint trying to collect stamps and colliding with international borders, trafficking, and visa difficulties. It’s actually very funny and interesting, and has Shennawy’s trademark design cleverness of using real scans and stamps to create fascinating sequential art.

Deena Mohamed is an Egyptian designer, illustrator, and writer. She first began making comics at eighteen, when she created the viral webcomic Qahera, a satirical superhero strip starring a visibly Muslim superheroine. Originally published in Arabic by Dar el Mahrousa in Egypt, Shubeik Lubeik was awarded Best Graphic Novel and the Grand Prize at the 2017 Cairo Comix Festival. She lives and works in Cairo, Egypt.

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series.