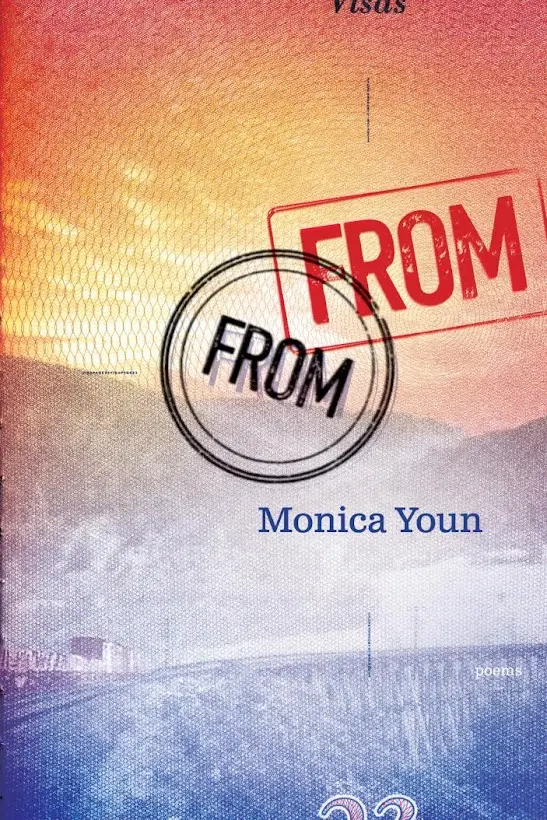

In her fourth poetry collection, From From (Graywolf, 2023), poet Monica Youn explores Asian American identity existing in the space between a homeland and a country of residence/citizenship.

In conversation with PEN America’s Community Outreach Gap Year Fellow, Saeri Plagmann for this week’s PEN Ten, Monica shares about subverting and questioning the racialized identities of Asians/Asian Americans through poetry (Amazon, Bookshop).

1. Wrestling with one’s identity, specifically the pressure to establish an “authentic” self versus conforming and assimilating to the dominant white society, is a theme I surfaced in a lot of your poems. It’s also a common experience among many from families that recently immigrated to the U.S. As the daughter of parents who immigrated to the U.S. from Korea, what conclusions have you come to in dealing with that sense of double consciousness? Is it possible to simultaneously embrace one’s ethnic heritage while also feeling a sense of belonging to American society?

I think that both types of belonging – to one’s heritage or to “America” – will necessarily feel different for immigrants, and then for post-immigrant generations. One of the things I wanted to do in this book was to create some space in the liminal zone between so-called “homeland” and country of residence and/or citizenship, and to see what sort of home I could create in that space. Hence the title for the book – I think that from from is actually the most accurate response to the question, “Where are you from?”

2. Your writing is very honest in its depiction of the viciousness of white supremacy and the suffering that often ensues from its pressures, standards, and expectations. I would say that this is a daring piece, but have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

As I start to hear some early responses about the book, some of them have been along the lines of “Oh no, I’m so sorry that such terrible things happened to you!” and that wasn’t my point at all. The poems don’t document the worst and most racist things that happened to me growing up or during the pandemic – that wasn’t what I was setting out to do. Nor was I trying to render the suffering that white supremacy and colonialism have imposed upon Asians and Asian Americans – others have and continue to do that work better and more validly than I feel that I could. Instead, I was trying to write about the evolving consciousness of a sense of belonging /unbelonging for myself and/or for other Asian Americans – within this country and within the dynamics of structural anti-Blackness, colonialism, heteropatriarchy and racial capitalism. If I could, I’d revise the book to make that distinction clearer.

“I also wanted readers to question their own habits of seeing, of reading, of consuming stories and roles, particularly those that might be classed as “exotic” or “foreign.” Generations of artists have “exoticized” these figures for a Western audience – how can I talk about them in a way that makes that process visible to a non-Asian reader without reinscribing that exoticization?“

3. What kind of impact do you hope your book will have on readers who are unfamiliar with the themes you discuss? What about readers who are familiar? What kind of conversations do you hope will be brought to the fore from this collection?

I think that the poems in the book will land differently with different audiences. There are some references, and some inside jokes, that will particularly resonate with Korean-American readers, with Asian-American readers, with immigrant and/or BIPOC readers, in a way that I hope is reinforcing and community building. But I also wanted readers to question their own habits of seeing, of reading, of consuming stories and roles, particularly those that might be classed as “exotic” or “foreign.” Generations of artists have “exoticized” these figures for a Western audience – how can I talk about them in a way that makes that process visible to a non-Asian reader without reinscribing that exoticization?

4. From From is very personal, both for you and for Asian Americans of all generations. How do you think poetry helped to articulate or translate these experiences better than if you were to have written it in a different format, like an essay?

If I had an existing message that I was trying to disseminate, I wouldn’t write a poem – I would write an opinion piece or a blog post. Poetry is how I work things out for myself – not a “thinking” process alone, but a process of language, which brings in the social, the emotional, the affective and the physical. When I started the longer poems in the book – the “Studies” and the long prose poem – I made a conscious decision not to know where the poem would go when I started it. I was hoping in this way that the reader could be a part of the journey, with me as we made discoveries in “real” time.

5. The phrase “once a lawyer, always a lawyer” comes to my mind. Does your poetry ever cross into that world of legal jargon and frameworks when you write?

I’m trying not to think of legal language as “jargon,” but as a poetic resource that warrants a place in lyric. A real breakthrough point for my writing was when I decided to stop treating my legal background as something irrelevant or even antithetical to my poetic practice, but instead to own my knowledge of legal language as a poetic resource. It’s a system of reasoning that is grounded in analogy, much like metaphor: to take a well-known example, in the Citizens United case, the Supreme Court treats money as speech, corporations as people, and elections as a marketplace. And because they have power, the Court’s statement of these equivalences remade reality in the image of their assertions.

In the new collection, I play with the rhetoric of this kind of “power language,” though obviously without any backing of real-world power, in a way that I hope exposes both its persuasive force and also its ultimate hollowness. One of my longer-term poetic goals is to expand the scope of the lyric to encompass more analytic registers, in the service not directly of truth but of doubt and of resistance.

“I wanted the publication of this book to be the start of a conversation, not the end of it, and I’m excited to see the conversation unfold, and to learn from that as a poet and as a person.”

6. You make references to Greek mythology in several of these pieces. Could you elaborate on the choice to interweave Greek mythology in the telling of the Asian American experience?

The Asian, and by extension the Asian American, experience has been interwoven with Greek myth since the very beginning – I wrote this section as an effort to redress the erasure – or the “de-racing” – of Asianness from these mythic figures and stories, to push back against the depiction of these figures as white marble statues and to broaden an understanding of these myths as both racialized and nationalistic. Greek myth – like so many other myths – was intensely nationalistic, and one of its overriding concerns was defining essential “Greekness,” often in contrast to an Asian other, which is defined as decadent, irrational, sexualized, exotic, magic, taboo – much as “Orientalism” has worked throughout the centuries, all the way up through Crazy Rich Asians.

Given the centrality of Greek culture to the West’s self-conception, it’s crucial that the Greeks were so obsessed with othering Asians. The Trojans, the Theban royal family, the Daughters of the Sun (a family that includes Circe, Medea, Pasiphae, and Phaedra), the Phrygians (the satyrs, Marsyas, the Asian mother goddess Kybele and her son Midas) and Dionysus, the “Asian god” and his Maenads – would all have been understood by the Greeks to be racialized figures from “Asia” – a Greek word referring to the region to the East where the Greeks had established colonies. As a kid I was obsessed with Greek myths, so for me this exploration wasn’t just an intellectual exercise but somewhere between a journey of self-discovery and an exorcism.

7. How does it feel to finally have this collection out in the world? How have you prepared for its release?

I tend to feel my way into poems – it’s a very instinctual process – and into the creation of a book. The poem doesn’t live for me until it reaches the mind of the reader, as if the poem is a musical composition and the reader is both the musician and the instrument. So I enjoy the process of preparing for a book launch – seeing how early readers respond to the book, and having deep exploratory conversations with interviewers such as you, who help me better understand what the book is and how it works. I wanted the publication of this book to be the start of a conversation, not the end of it, and I’m excited to see the conversation unfold, and to learn from that as a poet and as a person.

8. Your book comes at a time when we are seeing significant anti-Asian sentiment in the United States, as well as an increase in book bans. Do you see your work as a political piece? Why do you think it is especially important to have books such as From From be made more accessible?

Yes, the anti-Asian attacks show no signs of abating, even as the non-Asian American public turns its focus elsewhere. But so do other racist, anti-trans, homophobic, anti-Semitic, Islamophobic, and misogynist attacks – part of a wave of hatred that some of those who benefit from existing hierarchies are strategically inciting, and have been inciting along various fronts throughout history.

Just last week, I experienced a mild taste of what educators have been facing around the country – I had been scheduled to read from From From at a local public school system, but the school that had invited me was forced to cancel the event because of opposition from reactionary members of their school board who claimed my work was too politically sensitive. The teacher who had invited me had to disinvite me by phone, afraid to leave an email record out of well-founded fear for his job. I was sorry for him, for his colleagues across the country who are facing anti-black, trans, anti-gay and other supremacist censorship and other initiatives, and for students who aren’t getting the educational, medical, and practical support they need to survive the present, to understand the past, and to craft a sustainable future.

“It seemed ethically questionable to be writing about the way structural racism and racial capitalism have shaped the lives of Asian Americans without making it clear how my own life fits into this picture.“

9. What kind of challenges did you face as you wrote this piece? Was there a specific poem or section that you found particularly difficult to write?

My impulse in starting this book was that I very much didn’t want it to be about me, about my story in particular. It simply didn’t make sense to me to center myself in poems about larger racial dynamics. But after I had written about half the poems in the collection, the opposite impulse took hold. It seemed ethically questionable to be writing about the way structural racism and racial capitalism have shaped the lives of Asian Americans without making it clear how my own life fits into this picture. I wanted to reveal my own positionality, not only as a character in a poem or in a history, but also as a writer, actively shaping these poems to make readers visible to themselves in the act of reading.

10. What do you think is next for you? Do you already have ideas for your next poetry collection, or are you up to dabbling in something different?

I usually go through a lengthy fallow period after a book. I’m hoping that this one will be shorter than my usual rhythm. I’m starting to think about epic form and the re-crafting of myth, perhaps with reference to Korean cultural and artistic traditions. I want to explore collaborations more actively, to learn from practices off the page.

Monica Youn is the author of From From, and three previous poetry collections: Blackacre, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, Barter, and Ignatz, a finalist for the National Book Award. The daughter of Korean immigrants and a former lawyer, she teaches at Princeton University.