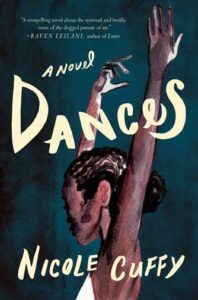

Nicole Cuffy’s debut novel, Dances, follows Cece, a ballerina who becomes the first Black principal of the New York City Ballet. In prose that is alive as the movements described on the page, Cuffy renders a story about the pursuit of art while balancing the realities of life—family, self doubt, and love, both of others and oneself. In an interview with Jared Jackson, Program Director for Literary Programs and Emerging Voices, Cuffy discusses the toll of the public gaze, the intersection of art and identity, and the act of empathetic imagination.

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

The first novel that profoundly impacted me was Toni Morrison’s Sula. I read it in high school, and at the time, I hadn’t read anything like it—Morrison’s command over language and character in her work, as well as the specificity of her descriptiveness and her ability to narrate the miniscule but so recognizable pieces of the human experience, was an ah-ha moment for me. I wanted to try to be a writer like that.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I think that, very often, people want there to be concrete truth in fiction. There’s this assumption of autobiography; people want the characters that I write to correspond with people I know in real life, and they want the experiences I write about to reflect my own lived experience. But fiction is an act of empathetic imagination. I imagine these characters, and then I try to imagine being these characters. Story itself is a matter of perspective—it happens through the lens of the characters I’ve made up. What I think good fiction can do is speak to an abstract truth. It can, like all good art, work as a mirror for the readers.

“There’s this assumption of autobiography; people want the characters that I write to correspond with people I know in real life, and they want the experiences I write about to reflect my own lived experience. But fiction is an act of empathetic imagination. I imagine these characters, and then I try to imagine being these characters.“

3. Your debut novel, Dances, centers a Black ballerina named Cece. At one point she says, “Ballet has always been about the body. The white body, specifically. So they watched my Black body, waited for it to confirm their prejudices, grew ever more anxious as it failed to do so, again and again.” What role does visibility, to be at the will of the “spectator’s gaze” play not only in dance, but in the novel at-large?

It has a lot to do with Cece’s Blackness. To be a dancer (or any other kind of performer), is to be observed as your job. And the better known you are in these fields, the more inescapable that public gaze is, to the point that it can begin to erode the line between public and private, and even one’s sense of self. But Blackness adds another layer to that in the form of Du Bois’s double consciousness: as a Black woman, Cece is navigating both her understanding of herself as a culturally Black woman, and her understanding of herself as a phenotypically Black woman in the context of the white gaze.

4. What did your creative process look like? How did you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

The most important thing for me is that I get the first draft written out by hand. It connects me much more to the language, and it helps me to keep my perfectionism managed, so that I’m not constantly distracting myself by editing and re-editing when, really, I just need to get the story out to begin with. I am a believer in the necessity of writer’s block. I think it’s part of the creative process; usually, it’s trying to tell you something. Maybe you need to reconnect with nature, maybe you’re burning out, maybe you’re trying to force something. It’s a cue to step back for a moment and look elsewhere.

5. Much like dance, the writing in the novel, though elegant, is visceral. How did you want to approach writing “the body?” What level of awareness did you want to evoke in readers that dancers possess inevitably?

Because dancers have this physicality, and they’re so hyperaware of their own bodies, I really wanted to evoke what that feels like for readers as well. I wanted the experience of reading this to be physical in a way; I wanted readers to bring their attention to their own physicality, even if they haven’t danced a step before.

“To be a dancer is to be observed as your job. And the better known you are in these fields, the more inescapable that public gaze is, to the point that it can begin to erode the line between public and private, and even one’s sense of self. But Blackness adds another layer to that in the form of Du Bois’s double consciousness.”

6. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about? Was there a book related to dance that helped in the creation of the novel or was there a void you hoped this novel might help fill?

My all-time favorite dance novel is The Cranes Dance, by Meg Howrey. It’s a bit niche, but it’s a really frank, bare look at what a dancer’s life can look like. It is also a wonderfully thoughtful exploration of mental health. It definitely fueled me through the writing of my own dance novel.

7. Cece’s brother Paul is also an artist. Both are consumed by their artistic passions, however, it leads them in different directions. What did you seek to explore in the relationship between artist and art, artist and passion, artist and, perhaps, self-destruction?

Part of what makes art such an interesting career is that it’s not just a job; it’s part of one’s identity. Because of this, art is often consuming to the artist. It’s something you have to learn how to balance, or else you can very easily be out of order. It’s no coincidence that artists tend to struggle with mental illness and drug addiction at very high rates. With Cece and Paul, I wanted to explore how much of a balancing act this can be. In the case of Paul, we have an artist who was consumed by his art in a way that led to self-destructiveness. In Cece, we have an artist who is also consumed by her art, but does not land in self-destructiveness the way her brother does.

8. What advice do you have for young writers?

Keep showing up. Even if you’re just staring at a blank page (or a blank screen) for twenty minutes on your lunch break, that’s what writing looks like sometimes.

“Part of what makes art such an interesting career is that it’s not just a job; it’s part of one’s identity. Because of this, art is often consuming to the artist. It’s something you have to learn how to balance, or else you can very easily be out of order.”

9. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

K-Ming Chang, Dawnie Walton, Hernan Diaz, Vendela Vida. And I’ll read anything by Jesmyn Ward.

10. Have you ever had to navigate censorship—or self-censorship—in your writing?

Sometimes, one of the harder things I find about writing fiction is that my characters aren’t me. They may be a little meaner than me, they may have less of a backbone, they may experience more tragedy. And because they are not me and they don’t have my experiences, it can require that I go to places that are uncomfortable for me. The temptation not to go is there, but that is self-censorship. Especially when dealing with difficult or controversial topics, I may feel like I have to be very careful navigating those things, and it can be scary because sometimes I have known people to confuse me with my characters but ultimately, I have to stick to the perspective of the character.

Nicole Cuffy is a D.C.-based writer with a BA from Columbia University and an MFA from The New School. She is a lecturer at the University of Maryland and American University. Her work can be found in Mason’s Road, The Master’s Review Volume VI (curated by Roxane Gay), Chautauqua, and Blue Mesa Review, and her chapbook, Atlas of the Body, won the Chautauqua Janus Prize and was a finalist for the Black River Chapbook Competition. When she is not writing, she is reading, and when she is not reading, she is probably dancing.