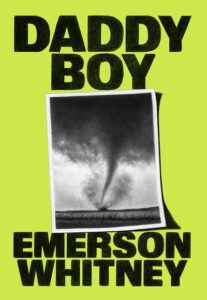

In their new memoir, Daddy Boy (McSweeney’s, 2023), Emerson Whitney chronicles his time on a storm-chasing tour through Tornado Alley as they think through familial relationships, weather, transness, and questions of control and submission.

In conversation with World Voices Festival Associate Director Sabir Sultan for this week’s PEN Ten, Emerson spoke about surrendering understanding, his writing process, grief, and disability. (Amazon, Bookshop).

1. Your memoir Daddy Boy follows you, at the end of a 10 year relationship, as you embark on a storm-chasing tour. From your earliest correspondence with the leader of the tour you positioned yourself as a writer who would document the trip. Did you always know that the trip would become a book?

As cheesy as this might sound, I have a tendency to feel like everything that’s happening is a book. I have always been dedicated to writing and recording what I’m seeing and experiencing. As long as I can remember, I’ve done this. My grandma tells everyone who will listen that from the time I could pick up a pencil, I was crawling around writing about everyone in the house. I see life through the lens of writing to the extent that I’m not exactly sure what life is if not a book? In this way, I went on the storm chasing tour totally knowing it was a “writing tour,” with different things to record than the ones I would be writing through if I was in my house, for example. At this point in time, I’d finished my book, Heaven, which was very much a recording of inner processes. Daddy Boy was a break from excavating the inward as my focus and the tour provided new scenery and new subject matter that I’d always wanted to sort of paint with.

2. The genesis of your love for weather and storms was born in your pre-adolescent years. Throughout the memoir you weave together your two week trip chasing storms in Tornado Alley with your childhood memories. Did the trip affect how you saw your childhood self? If so, in what ways?

With this book and going on the storm chasing tour, I really think it was the first time in adulthood I let myself engage in a “special interest” like that. I was diagnosed with learning disabilities that were labeled as on the spectrum when I was eleven. I was put into special ed. This was right around the time I first started going storm chasing. I didn’t really let myself truly enjoy this kind of interest that seemed super nerdy and deeply uncool, but returning to it for this book was so good. I was surrounded by other nerd-alert folks who loved this too and I felt cozy with them for the most part and glad to be embracing a kind of neurodivergent socializing. It also gave me much more compassion for my pre-teen self who I hadn’t really reflected on with any real care before. I was much more judgmental toward that part of me before this book.

“I have always been dedicated to writing and recording what I’m seeing and experiencing. As long as I can remember, I’ve done this. My grandma tells everyone who will listen that from the time I could pick up a pencil, I was crawling around writing about everyone in the house. I see life through the lens of writing to the extent that I’m not exactly sure what life is if not a book?”

3. At the book’s start you divorce your partner, a professional domme, with whom you had a lifestyle S&M relationship where you were the submissive partner. The relationship shifted as you began to have dominant urges and were no longer wholly comfortable in the submissive role. You write, “Who gets to be comfortable in their own skin?…I wonder all the time if I’m allowed to seek comfort.” What do you see as the connection between comfort and submission? How did your evolution towards becoming Daddy affect your sense of comfort?

I have always struggled with what “comfort” is exactly. I am the kind of person who wouldn’t use the highest setting on the windshield wipers of my car because what if it ever rained harder, for example, and I’d be stuck squinting and struggling into any kind of heavy rain. That’s the version of me who starts this book. The version of me who ends it, I think, is someone working at surrendering to peace and ease as much as I can. I’m accustomed to discomfort more generally. I’ve always had chronic pain as a result of genetic conditions I was born with and was medicated from a young age–they gave me hydrocodone when I was 10 and I was taught to just sort of deal. Through writing this book, I spent a lot of time learning about what would be a way to relate to pain and pleasure rather than trying to control or chase either.

4. When writing about trans elder & icon Miss Major, you wrote “An elder is like a map.” Why was it important to include her story and what map has she made for you?

Miss Major’s work in the world had a big influence on me as a trans person in California. I was a member of Gender Justice LA for nine years and I learned so much from Major and TGIJP, and the work of Bamby Salcedo and other elders, whose influence in the world is to make life more livable for the most vulnerable members in our community and to center that as our primary purpose. This way of being is how I aim my life. (I also really want to recommend Miss Major’s new book, Miss Major Speaks: Conversations with a Black Trans Revolutionary by Major and Toshio Meronek. It’s wonderful!)

“Through writing this book, I spent a lot of time learning about what would be a way to relate to pain and pleasure rather than trying to control or chase either.”

5. In your previous memoir, Heaven, you examine your relationship to your mother and grandmother. However, in this book your mother figures far less even as you explore your family dynamics through your relationship with your stepfather Hank and brothers Tye and Gunner. Why does your mother figure less prominently in this book?

In some ways, I’ve been such a student of my mom. I studied her very closely as a kid for survival reasons to some extent. My relationships with my brothers and the dad figures in my life feel much less known to me. I haven’t figured it out at all, honestly. It’s weird to get to the end of the book and still feel like that, but that’s also largely what this project was about, surrendering understanding.

6. The exploration of the nature of family appears thematically across your works. From your last memoir Heaven to the relationships you document in Daddy Boy including, your relationship with your ex, with your stepfather and stepbrothers, and with your fellow storm chasers on the tour, you consider various forms of family. Yet, you also chronicle your early and necessary independence that was born of your childhood family dynamics. How do you conceive of the role of family in your adult life?

6. The exploration of the nature of family appears thematically across your works. From your last memoir Heaven to the relationships you document in Daddy Boy including, your relationship with your ex, with your stepfather and stepbrothers, and with your fellow storm chasers on the tour, you consider various forms of family. Yet, you also chronicle your early and necessary independence that was born of your childhood family dynamics. How do you conceive of the role of family in your adult life?

I’m sitting right now with my best friend and my wife, the three of us live together, and they’re watching Temptation Island around me in the living room after we spent the day working together on projects around the house. Right now, two of the six dogs that live in this house with us are ripping up a toilet paper roll that I’d brought into the living room to help get a tick–a truly minuscule one–off the back of my friend’s leg. We’re laughing at the dogs who didn’t let the toilet paper sit for even a second before starting to shred it. How did they see it so fast? Family looks like this to me and it really is everything.

7. In the tradition of hybrid memoirs, your book is often in conversation with other works, writers, artists, and figures such as Michael Ondaatje, Young Jean Lee, Lauren Redniss, and even the movie The Parent Trap among others. When writing the memoir were these connections automatic or were they born in the drafting process? At what point did you realize your writing or specific passages were in dialogue with these others?

Yes! They were born from straightforward remembering and associating these works with the scenes or images I was working through. I wrote this book straight through. The only technique I used for these references was to not read anything that didn’t relate to the subject matter. I was able to sort of just associate with the resources I’d been engaging. I like thinking of writing as really my thinking and with this project, I was able to just let my thinking run.

8. You write, “I want to be gentle. Am I learning or unlearning?” Was writing Daddy Boy a process of learning, unlearning, or both?

Absolutely both. There’s endless indoctrination into colonization, capitalism, white supremacy, and all the interlocking systems of oppression that stem from these that I’m always working to unlearn–I can’t look at masculinity without seeing it as funneled through these systems. At the same time, I’m learning what is possible for me in this body, in relation to these systems..

“I am always very excited for my work to become yours. I like the practice of letting it go because this is where I really get to witness the deeply collaborative nature of writing.”

9. There are certain traumatic experiences you allude to or mention obliquely in the book. Where do you draw the line of what you will share and won’t share in your public writing?

This may seem basic, but I truly try to go with it. I am invested in autobiography and my friendship with writing to the extent that I trust it. If the words don’t come, I stop. There were places in this text that I just found myself not having more to say. I had a phrase or two or images I wanted to share, and that’s where it pooled and I tried to let it pool and then move on. I did have a pretty clear boundary in Heaven with not giving too many details about my mom’s life or work just to keep her safe. I’m very protective of my mom. She passed away last August and I feel suddenly like there’s nothing I’d intentionally keep out of any book. As much as I wrote about my mom and I, my prose was always very controlled. I wanted to share our story but absolutely burlesque any details that might make her more vulnerable than she already was. I have so much to say about my mom’s sudden passing. I’m so grateful for writing at this moment. I often can’t believe she’s not here. There’s been weeks throughout these months that I’ve wondered how I could keep living if she isn’t alive. She took her own life. I’ll never be the same, honestly. But I’ve never felt so cared for by the art of autobiography. I don’t know what else I’d be doing through this if I wasn’t writing and telling you the whole thing, really. Grief is also beautiful.

10. Writing is often a private and intimate process. Now that Daddy Boy has been released it also belongs to your readers. How did you prepare yourself for that shift?

I am always very excited for my work to become yours. I like the practice of letting it go because this is where I really get to witness the deeply collaborative nature of writing. How cool is it that y’all read this, associating wildly with these “marks” on the page, you know? I love this part. I’m excited for you all to change it with your reading and to make it totally new.

Emerson Whitney is the author of the critically acclaimed Heaven which was named a best book by Kirkus, Bomb, the AV Club, PAPER, Literary Hub, Refinery29, and the Chicago Review of Books. Emerson’s work has appeared in the Paris Review, the Los Angeles Review of Books, New York Magazine, and elsewhere.