Fighting Disinformation Can be Simple

In an age of improving technology, dwindling resources and increased disinformation, don’t minimize the importance of person-to-person engagement

This article is produced in collaboration with PEN America’s Journalism & Disinformation program. PEN America stands at the intersection of literature and human rights to protect free expression in the United States and worldwide. Disinformation poses a fundamental threat to free expression and democracy. For more resources useful for journalists combating mis- and disinformation, visit PEN’s Facts Forward hub.

By Elizabeth Lepro, PEN America

In 2022, ProPublica reporter Melissa Sanchez heard the harrowing story of a Wisconsin farm worker who had fatally run over his son with a 6,700-pound skid steer.

Sanchez was looking into deaths and injuries on small farms across the country, with a specific interest in how these events were affecting immigrant farm workers. That reporting would become a series co-produced with Maryam Jameel called “America’s Dairyland.”

Sanchez went to Wisconsin and looked for José, the father she’d heard about. She began by visiting a Mexican restaurant near the farm. Sanchez, who speaks Spanish, described the process of tracking José down in a first-person reporter’s notebook piece for ProPublica:

“[At the restaurant] I went straight to the kitchen and asked if anybody from Nicaragua worked there,” she wrote. “As luck would have it, a man from northern Nicaragua came out and told me he had once worked with José on a different farm. Later, during his lunch break, we went to his apartment and I watched as he sent José a voice message on WhatsApp about me.”

The result of Sanchez’s dogged reporting was a revelation: José hadn’t run over his son. Someone else on the farm had been operating the piece of machinery.

The story of a father inadvertently killing his son – which local news media ran with – was misinformation, based on a deputy’s initial interview with José. On top of the immense grief of losing a child, José was burdened with wrongful blame. The record would have remained inaccurate, if not for some old-fashioned investigative reporting.

My colleagues in PEN America’s disinformation and journalism program have been speaking with reporters, editors and journalism advocacy and professional organizations for the past 18 months about how they’re experiencing mis- and disinformation.

In 2021, PEN surveyed more than 1,000 reporters and editors about the topic. More than 90 percent said disinformation has affected their work in recent years, and 81 percent said it was a very serious problem. But when it comes to practices that can support journalists in their efforts to combat disinformation, many respondents reported their newsrooms weren’t implementing them.

Part of the reason may be that we’re overthinking what it means to combat disinformation effectively. The most effective debunking techniques don’t require fancy technology, but listening to people and coming up with innovative ways – digitally and in real life – to engage them.

Getting on the ground

While reporting the Dairyland series, Jameel and Sanchez recognized that reaching migrant farmworkers in rural Wisconsin was going to prove challenging.

“They [have] crazy work shifts – they work 60 or 80 hours – they’re very isolated, they can’t legally drive and they live on the farm,” she said. To reach them, she said, “we tried a lot of spaghetti on the wall.”

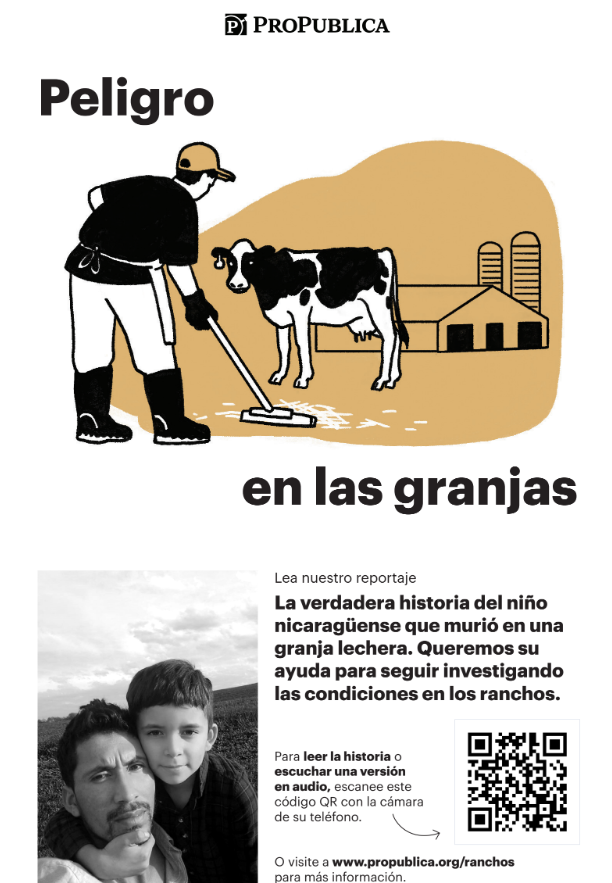

Sanchez first made what she called “clip art” flyers explaining in Spanish that she was a reporter looking to talk to farm workers. She and Jameel disseminated these flyers and others at small grocery stores across Wisconsin where they knew people would cash checks.

After the first story ran, ProPublica’s visuals team created more sophisticated flyers and a booklet of the story to distribute. The team also commissioned Spanish audio versions of the story.

“This was a way for folks to actually access the stories, because a lot of people have low literacy rates and can’t read,” Sanchez said. José, for instance, has a first-grade education. He told Sanchez he listened to the story about his son’s accident multiple times.

“It was through listening to the audio that he was able to actually understand how his kid had died,” she said.

In the PEN America survey, only 38 percent of journalist and editor respondents said they were regularly reaching out directly to develop relationships and trust with their audiences. That could be the result of reporters working with increasingly limited resources, dwindling staff support and mounting pressure to report quickly on trending topics–and it’s one reason misinformation is inadvertently spread by the people who care most about stopping it.

As the clip-art flyer example demonstrates, building community trust doesn’t have to be expensive or complicated.

Some of the demographics most vulnerable to disinformation include the elderly, people in rural areas and immigrant communities. Newsroom leadership can make a huge difference in combating mis- and disinformation if they give their staff time and creative freedom to meet community members where they are.

In many cases, the only way to get to the heart of stories is by talking to the people involved.

At PEN, in addition to offering guidance for journalists combating disinformation through our Facts Forward resource hub, we’re also doing on-the-ground community engagement to help reporters and community members recognize and fight inaccurate narratives.

We’re working in three key cities that are experiencing demographic and political changes: Miami, Dallas and Phoenix. In these locations, we’re investing in community-level resilience against false and misleading information through community house parties and partnerships with local media outlets.

PEN’s Trusted Messenger’s tip sheet offers useful information on community engagement for reporters and editors, with insights from reporters at Resolve Philly, Politico, the Texas Tribune and Votebeat.

Listen attentively and “early enough so that you’re allowing what you’re hearing from the community to actually shape your reporting,” said Annie Yu, director of engagement at Politico. “People respond to humans.” Her newsroom found success in filling information voids by responding to questions with regularity and a personal touch.

Tech as a tool

Social media is a breeding ground for mis- and disinformation.

In PEN’s survey, the vast majority of journalists surveyed said they needed to learn more about tools that could counter disinformation online, including bot detection and image verification tools.

Tools like Sensity.ai and Google reverse image search help in spotting altered or de-contextualized photos and videos. Organizations including The Markup and Bellingcat are providing great resources daily on using technology and Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) techniques to track down purveyors of disinformation and correct false narratives.

PEN America also provides insights and updates on generative AI and disinformation, as well as guidelines for using online verification tools.

That said, technology isn’t a savior – especially early forms of generative AI – and not every newsroom has the means to experiment with and set standards for expensive software and tools.

New technology can be exciting, but there’s reason to be cautious about how it’s used in reporting.

A widely accessible and reliable deepfake detection platform has yet to reach the market. Those that do exist can be cost-prohibitive for journalists working for resource-strapped outlets.

Multiple journalists, including the New York Times’ new director of AI initiatives, have pointed out that ChatGPT and other machine learning models can be useful to reporters in tasks such as parsing data and coding, but they still need a lot of human oversight to properly assist journalists.

“I worry about small, understaffed newsrooms relying upon these tools too much as the news industry struggles with layoffs and closures,” data journalist Jon Keegan said in a recent column for The Markup. “And when there is a lack of guidance from newsroom leadership regarding the use of these tools, it could lead to errors and inaccuracies.”

Bot detection and other online verification tools that can be useful in investigating potential sources of disinformation become obsolete when social media platforms change their standards, threaten to ban them, or dismantle them. That was the case for Bot Sentinel, the former graphical Twitter analysis tool WhoTwi, and, most recently, the social media monitoring tool CrowdTangle.

Metadata – the information attached to photos that indicates when and where a photo was taken – was once a trustworthy verification method, but now most social media sites scrub that data as a privacy measure.

The bottom line is that the world of technology to combat disinformation is fast-moving – new tools crop up and disappear – and in many cases, it means operating at the whim of private companies and the decisions they make about their platforms.

In PEN’s survey, only 35 percent of respondents said their newsrooms were implementing changes to attract and hire journalists that would ensure a wide variety of perspectives in the newsroom. Only 21 percent said their newsrooms were devoting resources to building relationships in communities where disinformation is likely to circulate.

In both cases, more than 60 percent of respondents said they thought these measures would be effective in combatting disinformation.

In the run-up to the 2024 election, editors will do well to support real – as in, human – journalists who have the cultural and professional know-how to stop misinformation where it starts. When it comes to debunking disinformation, use technology, but prioritize people.