Works of Justice: Sarah Wang on Bearing Witness

Works of Justice is an online series that features content connected to the PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Program, reflecting on the relationship between writing and incarceration, and presenting challenging conversations about criminal justice in the United States.

Sarah Wang slips into the past with ease. She possesses an archaeological precision in documenting her cultural history, yet draws the reader close by infusing the text with personal, intimate symbols. Imagery surfaces seamlessly: the perfume of pale orange loquats, the “artificial organ” of a dialysis machine, a missing child printed on a milk carton. Sarah’s voice is magnetic—at once lyrically resonant, and sharpened by an outspoken critical eye. Carefully examining the dark underbelly of American society, Sarah addresses topics from the militaristic violence inflicted on girls in juvenile detention, to the heightened surveillance of our private lives.

A fellow at the Center for Fiction and the Asian American Writers’ Workshop’s (AAWW) Witness Program, Sarah has written for BOMB, n+1, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Joyland, Catapult, Conjunctions, Stonecutter Journal, semiotext(e)’s Animal Shelter, The Shanghai Literary Review, Performa Magazine, Musée d’Art Contemporain de Lyon, and The Last Newspaper at the New Museum, among other publications.

Gracefully agreeing to answer a series of our questions over email, Sarah’s responses employ the same level of frank eloquence present in her published work—and reading feels as if Sarah is sitting calmly across the table, looking us directly in the eye.

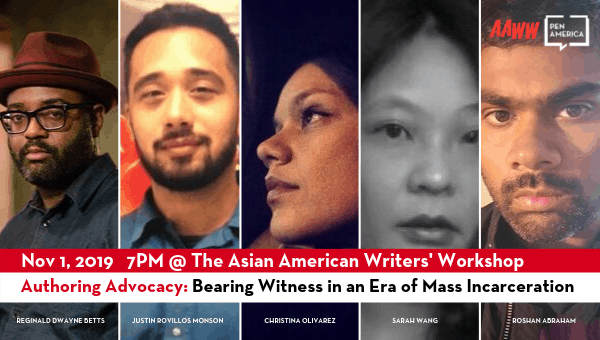

We invite you to be moved by Sarah’s interview, and then join us at “Authoring Advocacy: Bearing Witness in an Era of Mass Incarceration” on November 1, where Sarah will be reading and speaking, along with 2018 PEN America Writing for Justice Fellows Justin Rovillos Monson and Reginald Dwayne Betts, and peers in AAWW’s Witness Program, writers Roshan Abraham and Christina Olivares.

MAGS CHMIELARCZYK and LIZ FIORE: Can you describe your work with the AAWW Witness Program? We’re curious to learn what the act of bearing witness means to you, personally, and what you feel is the larger responsibility of writers when speaking and reporting on mass incarceration. What would you say is the potential of writing as an instrument of liberation?

SARAH WANG: Our cohort of four fellows—Christina Olivares, Roshan Abraham, Craig Campbell, and I—visited sites of mass incarceration and engaged in intensive dialogue with one another over a period of about five months. With different entry points and writing in a range of genres about mass incarceration, there were often heated debates on the Metro North heading back into the city after these site visits. We went to Manhattan Criminal Court one night to sit in on arraignments before having dinner with an activist and prison abolitionist public defender. Daniel Gross, the program’s director at the time, also organized a tour given by the commissioner at Westchester County Jail; we watched an RTA (Rehabilitation Through the Arts) production of Shakespeare’s Macbeth at Fishkill Prison; we met with the incarcerated journalist John J. Lennon in Sing Sing Prison, and sat in on arraignments and an asylum hearing at Varick Street Immigration Court. I should say that all of this was facilitated by Daniel, who coordinated these meetings and visits, who reached out to his contacts in order to gain access into jails and prisons, and to talk to people who are currently and formerly incarcerated, to activists and bureaucrats. One of the most impactful experiences of this fellowship for me has been my correspondence with a Chinese American poet, a woman who is incarcerated at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility. Each fellow was paired with an incarcerated writer with whom we wrote letters to; this facilitated crucial transmissions between writers on the inside and outside.

I wanted to briefly describe the program and our activities in order to better answer the very complicated question of what bearing witness has meant in this context. I have an embodied knowledge of incarceration that became, in many instances, activated and galvanized. I found myself occupying several different positions at once, which was confusing, sometimes scary, and also overwhelming. And in service of this embodied subjectivity, bearing witness often meant seeing through the whitewashing employed to alchemize shit into gold. I’m referring to both the sanitized PR tour the commissioner led through the county jail and the production of Macbeth that touted itself as a tool for rehabilitation that I read as a sort of minstrel show: black and brown men performing Shakespeare for a predominately white, touristic audience. In a very simple way, bearing witness also meant listening, watching, always asking questions that gave way to more questions, remembering, and then disseminating these experiences into the world in various ways: in conversation both with friends and people I would meet and in some instances never see again, through my own writing, and collaborative projects with people working in other fields. For me, bearing witness perhaps most of all has to do with feeling, which is to say that I often went home charged with an intolerable awareness of injustice. I cried a lot when I wrote letters to my pen pal and when I read the letters she wrote to me—not due to pathos or anything horrible like that but because different channels of possibility had opened up between us, two people who had never met before, who live quite different lives but who also share similar histories. Giving this kind of space to another person, and having it given to you, is deeply moving.

In terms of writing as an instrument of liberation, I really have no idea about what liberation means in the world we live in today. I know that writing can do things. I know that writing is the most powerful act I can fulfill. My pen pal says that writing letters is what keeps her going. Writing can provide a map of coordinates that lets you know where you are and, perhaps, where you’re going and where you’ve been.

CHMIELARCZYK/FIORE: In January of this year, you were featured in an AAWW panel on carceral language, which has saturated our perceptions of criminality and punishment. Do you believe that writing can reject those ingrained perceptions and subvert our assumptions surrounding incarceration?

WANG: When I was a teenager, I knew a girl who was serving time for solicitation and drug possession. She was 14. Using one type of language, she was labeled as a prostitute, a drug addict. But using another language, we can say that she was a victim of child sex trafficking and domestic violence who had been pimped, abused, and controlled by a violent man who had ripped her hair out in fistfuls. Think about the disparity between these two sets of languages, about what they say, about their intention and purpose when deployed.

Immigration court, for example, calls detainees “respondents” rather than defendants. Detainees, not prisoners. They no longer say “deportation,” they call it “expedited removal.” This is a term more fitting to cleaning my cat’s litter box than for humans. When a word becomes (rightly) stigmatized with human rights abuses, they just change the language to an obscured version of itself. Of course, the action remains the same. Yet the semiotic differences between criminal court and immigration court are basically nonexistent. Detainees, or respondents, wear orange prison uniforms. The courtrooms, benches, judge’s bench, witness stand, clerk’s station, Department of Justice seal, and American flag, are nearly identical in criminal and immigration court.

Another terrifying instance of language being used against us to perpetuate carcerality was made apparent when I visited Westchester County Jail. The commissioner referred to the incarcerated population as “clients.” Excuse me? This word gives incarcerated people false agency that they don’t actually have. He also emphasized that the correctional officers were sensitive to calling people by their preferred pronouns. First of all, I have no idea if the correctional officers actually do this. And second, this is all uncannily identical to the way that the alt-right uses stolen left-wing language to pervert progressive terms and camouflage hate speech, racism, and misogyny. The commissioner boasted that the jail offered its clients college courses, crochet classes, mindfulness meditation, and trauma-focused yoga as well as cognitive behavioral and group therapy and anger management classes. How progressive, you may think. It’s beginning to sound so good that you may want to attend this program yourself, forgetting that it is jail. The emperor’s clothes fell away when I talked to two incarcerated women in the dayroom near the end of our PR tour. They laughed when I asked them about which of these programs they were offered and participated in. One woman said that they had two options: earn seven dollars a week working full-time in the laundry room or kitchen, or endure being locked away in their rooms all day. Here it was, slave labor and mass incarceration as usual; progressive programming was not only an illusion but an outright lie.

When we write, we are creating histories. When we write our own stories, and the stories of those who are unable to write their own, we are choosing to not submit to language used in service of sanctioning abuse, slavery, and violence.

CHMIELARCZYK/FIORE: Your nonfiction work often combines deeply personal experiences with sharp cultural critique. How do you decide what to reveal to the reader, and what to keep hidden? Do you feel there is a catharsis that comes with unburdening your own memories?

WANG: I often keep what I hide in plain sight. In my fragmented writing, which some people call poetry, much of the meaning is only legible to myself—but it’s there. In some way, all of my writing is a letter to myself. What I choose to reveal is what I want to tell myself at a given time, and in turn, what I keep hidden is what I don’t want to hear about myself. At the same time that my writing is a letter to myself, there’s always another addressee, or many addressees. So it’s also about what I want or need to tell someone else who may or may not ever read the writing.

As far as catharsis goes, I don’t believe in it. I don’t feel unburdened when I write. It’s painful; it’s an act of jouissance. I believe in repeating myself over and over again until I’m sick of hearing myself. I annoy myself until I’m so annoyed I don’t want to hear myself anymore. Writing is about locating all the knots that have been tied inside of you and pulling at them, but the knots never unravel. Unraveling is not the point. Instead, you get tired of pulling and just let them be. You relegate yourself to living with the knots inside of you. Maybe that’s the opposite of catharsis.

CHMIELARCZYK/FIORE: “I often think about women’s work, women’s responsibility, the emotional and domestic labor we perform,” you write in a lyrical essay on your grandmother’s path to professional and emotional independence. Women in the face of hardship, specifically generations of migrant women, seem to be central to your work. Could you speak on the experience of documenting the lives of women who are closest to you?

WANG: These are the stories that lodge themselves inside of me. Much of my family history has been erased by war, by imperialism and political upheaval. I feel like my family has been dispossessed of its history. When my grandparents fled Mainland China in the late forties, they never again talked to or saw the families that they had left behind.

In psychoanalysis, it’s not about what happens, it’s about what you do with what happens. For example, if the analyst is late, the analysand may confront the analyst in anger. She may repress her annoyance and let it accumulate over time until it is unbearable. She may think that her analyst doesn’t care about her and is sending her a message by way of being late. In this way, what I do with what’s happened is to document the stories of the women in my family, to find a way to speak, and to find a language with which to speak.

CHMIELARCZYK/FIORE: Writing on topics as heavy as mass incarceration and systemic violence can take an emotional toll. Taking on these dark topics creatively and intellectually can be personally harrowing. Do you have a process to protect your private or interior world? Do you have any hobbies or rituals that allow you to step away from the weight of it all? Have there been points throughout your career when you lost the motivation to write? (And if so, what pushed you to keep going?)

WANG: I tend to lean into these things rather than protect myself from them. I have been in psychoanalysis for nearly a decade; this is the closest thing I have to a ritual. It’s a place I can continually return to and find something to keep going, whether that means looping back or moving through another repetition. Speaking in this way week after week is a strange process that gives birth to itself, constantly mutating and finding new ground beneath the old ground. Earlier this year, I told my analyst, “It’s been nine years.” He said, “Good. Nine years and nine more.” I imagine a future where the years continue doubling.

The fear of not being able to write strikes daily. I’m always losing and finding my writing practice. What keeps me going? I don’t really know how to do anything else. Deadlines. People asking me to work on fun projects. Being accountable to another person, whether it’s an agent or editor or collaborator. I’ve also turned to writing when there’s nothing else. I don’t want to sound religious, but it has saved me when I’ve been in the thrust of despair, if only for allowing me to see and feel and apprehend—all of which are elusive when the world has broken you.

CHMIELARCZYK/FIORE: In the past 5 years, the public’s awareness of mass incarceration has increased tremendously. How has this affected your writing on the subject—your process, approach or urgency? What would you say to the people who still don’t see a problem with our country’s current justice system?

WANG: Public awareness has nudged me in the direction of thinking about my own life in different ways, and it has allowed me to give myself permission to write about the things that have happened to me. Public awareness has also allowed for dialogue that has helped give voice to what is actively hidden and, in turn, opportunities for more voices to be heard. Years ago, I applied for a fellowship with AAWW and proposed that I work on issues dealing with mass incarceration. I was told that this was too large of a scope for the organization. There were no resources with which to explore these issues. A few years later, after mass incarceration became a topic of national discussion and a matter of interest for more people, the Witness Program came into existence, which has given me more points of access with which to think and write about these issues in new ways.

I would say to people who don’t take issue with the current justice system to call me. I will tell you some things that have happened to me and to countless people in this country and around the world, things that are still happening to me. I will tell you stories about how unjust our system is, and how violence against certain people, against women and children, and against people of color, are not only sanctioned but perpetuated by this system. I will tell you stories and maybe you will feel something. Maybe you will use this feeling by turning it into action.

RSVP to see Sarah read live at “Authoring Advocacy: Bearing Witness in an Era of Mass Incarceration” on November 1, 2019.