Works of Justice: An Interview with Writing for Justice Fellow Justin Rovillos Monson

Works of Justice is an online series that features content connected to the PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Program, reflecting on the relationship between writing and incarceration, and presenting challenging conversations about criminal justice in the United States.

“All of my poems

Have folded away

Into the swollen humidity

Of July—all clouds

Renegade verbs?

Unsung forms?

Let them sing

Let us join them”

—Justin Rovillos Monson, excerpt from Poetics: Mid-summer 2016 (Fragments of a Freestyle)

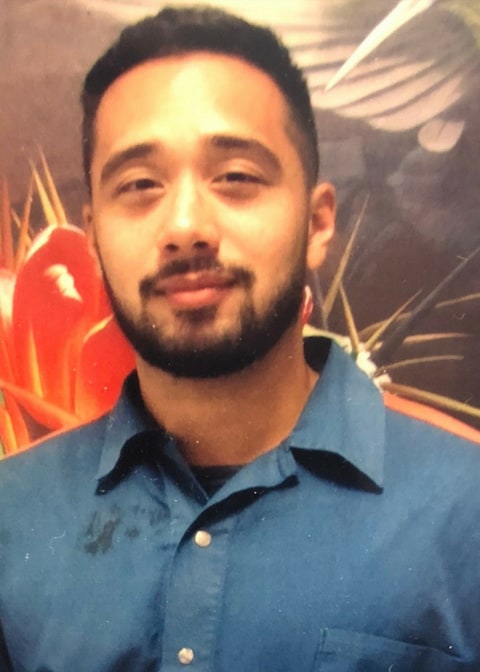

Straddling hip hop, spoken word, and more formal poetic influences, Writing For Justice Fellow Justin Rovillos Monson’s AMERICAN INMATE is a sequence of poems in the form of a literary mixtape.

Straddling hip hop, spoken word, and more formal poetic influences, Writing For Justice Fellow Justin Rovillos Monson’s AMERICAN INMATE is a sequence of poems in the form of a literary mixtape.

The poems sample and remix various sources, exploring the desires, pains, and experiences of being a young, Filipino-American man in prison. Monson’s work strives to, in his own words, balance the “sentimental pain and struggle of prison with a more explorative gratitude.” The result is an explosive lyric that boldly—and beautifully—challenges the two-dimensional portrayal people in prison are often allowed. In the tradition of lyric poetry, Monson’s collection-in-progress offers snapshots of his life: old timers on the yard who offer the “Youngblood” advice, stories that span familial generations, coming-of-age, music, and romantic love.

Now open for applications until May 15, 2019, 11:59pm EST, PEN America’s Writing for Justice Fellowship commissions writers—emerging or established—to create written works of lasting merit that illuminate critical issues related to mass incarceration and catalyze public debate. In the following Q&A interview with PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Program Director Caits Meissner, Monson shares his inspiration, motivations, philosophies, and words of advice for those considering applying to this year’s Fellowship opportunity.

CAITS MEISSNER: What inspires you to write?

JUSTIN ROVILLOS MONSON: Writing gives me an avenue to pursue meanings for my life that would otherwise be property of the state. In a legal sense, my body is owned by the State of Michigan. And one might wonder: If I—or anyone else, for that matter—become successful in here, or upon release, whose success is that? The state’s? My own? Even someone never introduced to Foucauldian thought can recognize the major implications of the body and mind in such a question. Writing and publishing allow me to give material for other interpretations and meanings for my own life. So I think there’s certainly a sort of rebellion inherent in that idea, that I’m hijacking or contrabanding my body back from the state by expanding and publicizing the products of my mind. That trope, closed mouths don’t get fed, comes to mind. Closed mouths don’t get heard.

MEISSNER: What inspires the project you submitted? What do you hope to achieve with it? Is there a particular life experience that you draw upon when creating?

MONSON: AMERICAN INMATE has so far been influenced in two major ways, regarding content and form.

From a content perspective, I’ve been deeply influenced by the ability to experience joy and love, even in such a restrictive environment. In recent years, I was able to be part of a relationship that—no hyperbole—changed my life more than any cage ever could. Even though things didn’t work out between she and I, it’s all love for me. So, something very important to me in my current work is to counterbalance the sentimental pain and struggle of prison with a more explorative gratitude and a reaching intimacy that I think is underrepresented in “prison” writing.

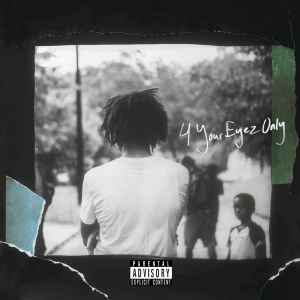

Formally, AMERICAN INMATE has been influenced, in a very concrete manner, by the music I listen to. Kendrick Lamar’s Damn. and J. Cole’s 4 Your Eyes Only are nothing short of masterclasses in poetic sequencing and narrative, respectively, and I continuously turn to both albums for inspiration. And those are just the tip of the iceberg. So, the desire and tendency to weave rap lyrics, philosophy, personal narrative, and pop culture references has been sort of a natural instinct for me—probably because my choice of music has pushed me to consider not just the artist as writer/MC, but also as producer/DJ. Hopefully this sort of sampling and remixing of ideas can influence more encompassing works, rather than one-dimensional plays on and, more so, interpretations of, theme.

I’d love for readers to sort of get lost in the jungle with AMERICAN INMATE. I’m very attached right now to the idea of stacking samples on samples on samples, just layers and layers of references and voices that interact with one another. I think there’s a lot of value in something that makes you work to develop an understanding of it, that offers fresh perspectives whenever you follow some of the various hidden trails, that puts you in a position to find your own way out, or even stay for awhile.

“I think there’s a lot of value in something that makes you work to develop an understanding of it . . .”

Ideally, AMERICAN INMATE would influence the meta-narrative of incarceration in our country. To put it clearly, I don’t just want to add to the conversation; I want to help change the terms and rules. If we really want to push social change, then the ways we talk about, and recognize the actions of, incarcerated individuals need to transcend both liberal and conservative dialect. I want to blur some boundaries. For instance, if I write a poem, is it a “prison poem”? Am I by necessity a “prison poet”? Why? It’s inevitable that the prison environment I somehow keep awaking to will seep into my work, but I don’t think that should characterize me as a prison poet, first or by necessity. I want to be able to lay out my own body and mind, not the sentiments of “the prisoner” as an abstraction or idea.

When I was fresh out of high school, some friends and I started to make music and put together an ad-hoc company—Cold World Collective Multimedia Group. The mood was exciting. We were these young hustlers, and the more music we made, the more we started to realize that there’s no degree or authority that could give us what we wanted—we had to make it ourselves. This idea—this freedom—had been growing in me since school, when I was engaged in some less legal forms of hustling. So, just before I came to prison we started to put together a mixtape that was never finished. In retrospect, my bars left a lot to be desired: I was certainly the technical-lyrical weak link when compared to my main counterpart on those songs—shout out to Kristian!—but I still am really proud of myself and of my friends for seizing that fire so early on in life. That period of my life is what made me a creator. Learning to hustle might be the single most important thing I learned in my youth.

MEISSNER: What does being a fellow in the Writing for Justice Fellowship mean to you?

MONSON: It means I have an incredible, maybe once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. It means the hard work is just beginning. I’ve gotten a lot of congratulations from family and close friends, but it’s sort of funny because I’m very much so looking ahead to the coming months of work: straight-up tunnel-vision. I feel like I have an opportunity here to offer some representation for incarcerated individuals in America. I wouldn’t even begin to say that I “speak” for my incarcerated peers, but I certainly feel a level of responsibility to anyone who’s been touched by the criminal justice system in some way, on either side of the fence.

MEISSNER: How has writing impacted your life?

MONSON: Writing expanded my world at a time when everything felt so small and suffocating. As embarrassingly cliché as it is to say, writing gave me a breadth of hope. Prison is very effective and efficient at making one’s mind fit into a box. Often, the only connections you have to the “world” are some family and friends, if you’re lucky, and the TV. The environment tends to spread into your mind and mold you in ways that you don’t even notice until you realize you’ve forgotten who you are outside of the walls. So for me, recognition of my work, on any level, has been a major factor in my intellectual and social growth. Being heard has expanded my world and pushed me to keep looking forward toward my physical freedom.

“Writing expanded my world at a time when everything felt so small and suffocating.”

MEISSNER: What has been the most exciting/scary/intimidating part of this project?

MONSON: The idea that I have a deadline to essentially write a sequenced collection of poetry is both invigorating and intimidating. The pressure is something I take very seriously, which causes a lot of stress and keeps me up most nights. To be totally transparent, one of the major goals for AMERICAN INMATE is to win or be shortlisted for an award. I’m aware that maybe that goes against some people’s professional artistic inclinations, but it has been very important for me to be clear about what I want, because, for now, I may only have this one shot to get it right. And perhaps I’m not even operating at that level, but I’ve got to shoot for the moon. The impetus to create something that can reach toward my own high expectations—and on a timeline, at that!—is, and will continue to be, the most exciting and intimidating aspect of making AMERICAN INMATE. Then again, there’s always room for a remix.

MEISSNER: What would you say to encourage others to apply for the fellowship?

MONSON: “Go and get it. Be thorough, be relentless, and be grateful every step of the way.” That’s what I would say. There’s this Joe Budden song where he says there are three types of people in the world: you make things happen, watch things happen, or wonder what happened. Though I can’t 100 percent get with the reductiveness of such a worldview, I unequivocally believe in going out and grinding to get where you want to be. So I’d encourage people to not be intimidated by others work, by any institutions, or by any idea that stops you from pursuing your own projects. All those things are artifice, they don’t really matter. A lot of people place stock in the idea of “believing in yourself,” which is definitely important, but I’m a firm advocate of just going and shooting your shot, whether you believe in yourself or not. You’ve just gotta go and get it.

Applications for the Writing For Justice Fellowship are open until May 15, 2019.