Works of Justice: An Interview with Prison Poet Laureate Eduardo “Echo” Martinez

Works of Justice is an online series that features content connected to the PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Program, reflecting on the relationship between writing and incarceration, and presenting challenging conversations about criminal justice in the United States.

This September, in commemoration of the Attica Riots, PEN America and The Poetry Project launch BREAK OUT: a movement to (re)integrate incarcerated writers into literary community. Throughout the month, over two dozen local reading series in New York City—and across the country—will feature the work of a currently incarcerated writer. One of our featured writers is Eduardo “Echo” Martinez. Learn more about the effort here.

This summer, in my role as a PEN America Prison Writing intern, I had the opportunity to curate the work of incarcerated writers for the BREAK OUT series, a movement to (re)integrate incarcerated writers into literary spaces on the outside. During this process I was immediately gripped by the poetry of Eduardo “Echo” Martinez. A poet myself, I am moved by how Echo utilizes lyricism to explore themes of unity without abandoning the “I.” The BREAK OUT movement asks a critical question: How can we bring voices from behind the walls into authentic relationships with our existing communities? In the spirit of pursuing literary relationships, I was inspired to interview Echo on his written process and literary journey.

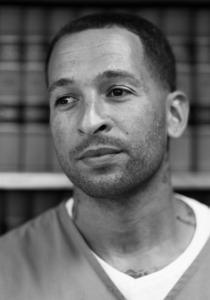

Eduardo “Echo” Martinez, recently honored as Florida’s first Luis Hernandez Prison Poet Laureate, roots his poetry in the struggle for liberation. Exploring freedom and power within the boundaries of an oppressive carceral system, Echo’s lyricism expresses his urgency: “We can all be heard, even if we have to scream,” he writes. His work draws on the past and the future of political activism, and becomes another vital voice in the timeless fight for justice. Consistently evoking a sense of home and intimacy, Echo artfully offers his readers the names of people and places who have both grounded and driven his life and creative journey. “Where I came from, where I’ve been, where I’m at, or where I’m going. Each one of those sentences holds hands with relevance,” he writes.

Eduardo “Echo” Martinez, recently honored as Florida’s first Luis Hernandez Prison Poet Laureate, roots his poetry in the struggle for liberation. Exploring freedom and power within the boundaries of an oppressive carceral system, Echo’s lyricism expresses his urgency: “We can all be heard, even if we have to scream,” he writes. His work draws on the past and the future of political activism, and becomes another vital voice in the timeless fight for justice. Consistently evoking a sense of home and intimacy, Echo artfully offers his readers the names of people and places who have both grounded and driven his life and creative journey. “Where I came from, where I’ve been, where I’m at, or where I’m going. Each one of those sentences holds hands with relevance,” he writes.

Echo has been published in Cuban Counterpoints, Scalawag, Don’t Shake the Spoon: A Literary Journal, the Miami Herald, Anthology BeKindr, and PBS N.Y. The lyrical nature of his poetry extends into this interview, which often times, reads just like a poem.

EMSELLEM: In the Exchange for Change interview “Sitting Down With Echo Martinez,” you say, “I was writing her poetry before I knew what poetry was.” The poem recipient, now your wife, was a girl living on the tier beneath you in county jail. In prison, poetry has a variety of applications and currencies. How has poetry served you—as a means of correspondence? Catharsis? Commerce? Currency?

MARTINEZ: Poetry has served me like a waiter, like a daily special. It’s allowed me to sit at the table with my thoughts and my imagination. It’s provided me with a menu of inner dialogue. It’s been the host to my soul’s microphone, my audience: a box of crayons. Surroundings in prison are dull and somber so in my mind I use poetry to add season to meals, neon to boring colors, and bend rules and measures like a plastic ruler. Measuring my conscious like a tailor, keeping my mind fresh and fitted in a prolific perspective.

No one really listens to us so I write to listen to myself. Having colorful conversations, enlightening my environment, keeping this concrete graveyard vibrant. I wrote the truth, one coated in emotion, to a young lady locked up a few floors beneath me. Nineteen years later we’re married, and she’s the most poetic thing about me, but it all started with words. It’s funny how people from my childhood are always like, “Yo, you’ve always had a way with words.” And I’m like, damn, why you ain’t tell me that before, but I guess like everything else in this world, words need time to grow. Maybe I should have kept my answer simple and said poetry has been a catharsis behind these walls . . . but then again, who am I to deny words freedom or space to grow?

“That’s what poetry is, a free feeling.”

EMSELLEM: One thing that drew me to your poetry is how incredibly ambitious and bold it is. How does your writing process allow you to achieve this ambition? How do you know a poem is finished?

MARTINEZ: My poetry isn’t really ambitious. It’s hungry. . . . It’s starving on the edge of desperation. It’s the lyrical hunger pains that make my words bold. I don’t concern myself on how a lie might feel about the truth, or offending people that are purposely offending others. That’s what poetry is, a free feeling. Besides, defense doesn’t always win games . . . at least not behind these fences.

My poems are never finished, and I’m not the revision type, because every time I come across one of my poems I have to fight the urge to touch it. I’m never satisfied. I always feel like there’s something missing. To avoid that conflict, I just write until that thought needs time to catch its breath, and that is when I am finished. But the thought never stops— it’s just resting, if that makes any sense. For instance, the poem you mentioned, “Provocation,” I read that now and I want to expand and elaborate on it some more. Words grow, remember, so its shoe size is bigger. Those words are ready to run harder and farther. In society truth is always at a distance. I’m constantly on its heels like a pair of socks . . . 10 toes on my flow.

EMSELLEM: One of my favorite pieces of yours is “Provocation,” in which you invoke the names of freedom fighters across history and identities. You write each figure, including yourself, into one collective spirit—interconnected and embodied through the use of “we.” Tell us about this approach. How can writing be used to form relationships across time and place?

MARTINEZ: Provocation is an experience. A fusion of history and present day, plantation to prison, guards to slave masters, prisoners to slaves. Unity is an endangered attribute in prison, but you might catch a glimpse of it every now and then depending on the circumstance. A man can only take so much. Provoke any animal in a cage, and it’s only a matter of time. And this is Florida, where dogs have more rights than prisoners. This is America, where they abort babies and adopt puppies.

I use “we” in the “Provocation” piece because I know what pride tastes like, I know what hate looks like, and how easily power can be abused by men unworthy of it. Your modern day lucifer effect, the Stanford Prison experiment, proves that. I use “we” in the “Provocation” piece because no matter how biased or racist some guys here may be, this system made them like that. And there comes a time when that gets cast aside. Like in the piece “Provocation,” ‘cause these days walking on water don’t cut it anymore.

Medical science has proven that the brain is not fully developed until at least the age of 25. It’s not capable of making logical, rational, and critical decisions. It’s emotionally driven. Young Black and Latino officers have become highly oppressive, their mentality is sickening and they think that shit is cool. Macing, caging, and beating men that have been in prison before they were even born. But it’s the system that hires these fresh outta high school kids and puts them to govern over men in hostile environments expecting them to make logical decisions . . . and they don’t, what they do is provoke.

EMSELLEM: Your poetry is complex in its stylistic fusion of lyricism, spoken word, hip-hop, epic, and more. If you were to invent a poetic form, how would you define it? And what would you call it?

MARTINEZ: You say my poetry is complex. I have opponents when I write. Sometimes it’s someone I can’t see, sometimes God or society. Sometimes it’s me. I play mental chess with the pen. I’ll sucker punch pawns or push them, curse the bishop then pray for it, crack your rook then mend it. One night the queen bows so the king can Knight ‘em again. I’m from hip-hop salt water, black top crossovers and sidewalks. I dress every line with experience and purpose . . . but I’m still not sure what my form is.

As for inventive form and defining it, I guess by combining abstract and concrete. Some eclipse kind of shit, like sun and moon crossing paths. Giving your conscious a backstage pass. I’m not into fooling myself or the reader. I want us to see together what goes on in life’s dressing room, tour bus, prison bus.

As for what I’d call it, probably something like “Sandlot poetry.” Sandlot is a term we used as kids playing tackle football at a park or backyard. No script, no playbook, flags, or huddles—just a bunch of barefooted kids getting dirty, playing hard, and reacting creatively during a game. Getting hurt while having fun, but that’s OK, because while you’re out there you’re part of something, but most importantly you’re free. You can dance in the end zone, or take a knee if you don’t agree . . . because you’re young, free, and with plenty of time to grow . . . just how words should be. So yeah, right now I’m thinking “Sandlot poetry.”

“My responsibility is truth and awareness. I’m not attempting to push the envelope. I’m pushing the Post Office.”

EMSELLEM: You were recently named the 2019 Prison Poet Laureate in Florida, an initiative awarded by Exchange for Change in collaboration with O, Miami Poetry Festival. What does this title mean to you? Does this title call for new responsibilities/writing/actions?

MARTINEZ: What 2019 Florida Prison Poet Laureate means to me. It means I got 97,000 incarcerated names on my back like a jersey. I represent them and it’s my obligation to do so justly. It means Exchange for Change and O, Miami Poetry notice me and recognize the importance of what’s going on behind Lady Justice’s blindfold. My responsibility is truth and awareness. I’m not attempting to push the envelope. I’m pushing the Post Office.

Now D.O.C. has a spotlight, or should I say a sniper’s sight on me, ‘cause words have power, young or grown— they can be convincing or convicting. I remember my first fight with stage fright, I gave it a black eye. Ever since then I’ve been in the paint with boots tied tight, making noise with or without a mic . . . ‘cause I think it’s about that time, that we’re all heard, something like a poetic prison reform.

Read Echo’s statement on being the inaugural Prison Poet Laureate

Read a selection of Echo’s poems

Listen to Echo read poems on Prison Poet Laureate Radio

Watch Echo on PBS Newshour

Catch Echo’s work live on September 5, 7pm at the Rally Reading Series, held at Pete’s Candy Store in Brooklyn, NY. If you’re a young person, you can also check out Echo’s work live on September 3, 5:30pm at First Draft, Urban Word’s youth poetry open mic night. Learn more about the BREAK OUT movement.