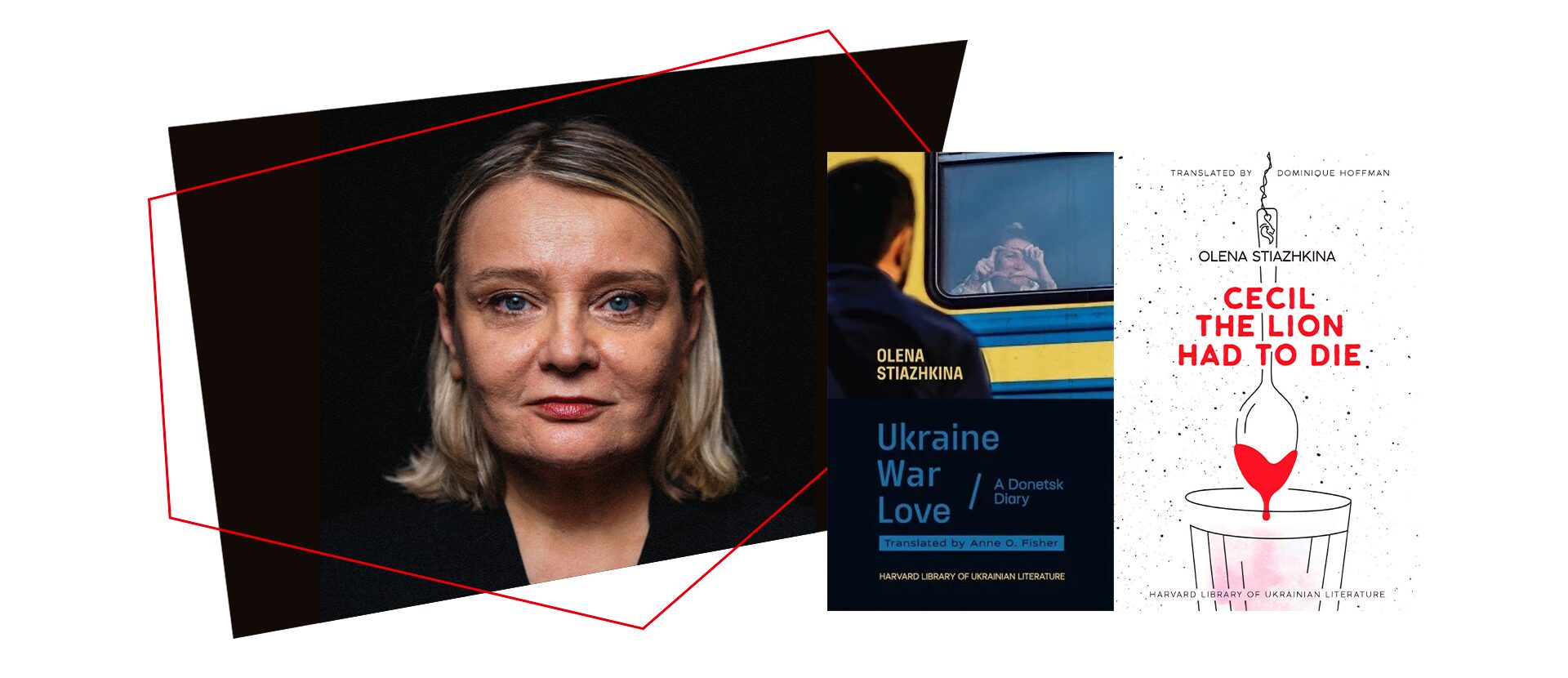

Meeting writer, historian, and PEN Ukraine board member Olena Stiazhkina, it is easy to see a person who seems softened by the war, having seen it, lived it, written about it through its various iterations. She speaks softly, kindly; humbly, apologizing that her English is not perfect and might need more lessons.

But behind her modest demeanor, her strict professor mannerisms are not lost. Stiazhkina threatened low grades for humans for not learning from past mistakes, and sat up stick-straight, answering questions with a sharpness of words and wit. Her strength – equal parts unassuming and obvious – was a reflection of what has come to define Ukraine’s response and resilience against the Russian offensives.

Stiazhkina visited PEN America for an interactive hour with the staff. Within the grim backdrop of the ongoing war, a photo of a cat in a military shelter in the frontline was passed around, and many dark jokes were cracked. She sat down for an interview following that.

Discussing her books, Ukraine, War, Love: A Donetsk Diary, translated into English by Anne O. Fisher, and Cecil The Lion Had To Die, translated into English by Dominique Hoffmann, both published by the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute earlier this year, Stiazhkina spoke about the role language plays in a war, from giving up Russian in solidarity to building a community in Ukrainian.

How did you first take to writing? Why did this medium appeal to you?

I don’t think I have an honest answer, really, because every day when I stop to think, I have absolutely different answers. Sometimes I think that writing is a way of warding off loneliness, but sometimes I think that solitude is one way which I want to have. Sometimes I think that I need my own place in this universe, in this world, and only writing can give me this place when I can be myself, and I can be brave and be free from all these problems. And I can speak. I can tell some stories, and I can talk to myself and calm myself down and make myself less afraid, and maybe my readers can get this feeling and make themselves less afraid.

In Ukraine, War, Love: A Donetsk Diary, you write that the Ukrainian language becomes the language of “safety and life, “when it is the only indicator of something living.” Do you think Ukrainian as a language has been in survival mode for a long time?

Yes, there’s only one thing about the Ukrainian language that is about survival and security, but the most important thing is Ukrainian is the language of freedom, anti-colonialism, decolonialism, anti-imperialistic pursuits, struggle, fighting, and that is why now this language is not only for us; this language is for all countries that need to be free. That is why I think that we are extremely needed in translation into Spanish, for example, or Indonesian languages or Malaysia, Chinese, because the main thing that we have to export is freedom.

As a reader, how have books shaped your identity? Did books reflect the reality you found yourself in?

Ukraine, in Soviet time, had really brilliant translations. And that is why a lot of excellent books from English and American writers, from German and Italian writers, have come to readers in Ukrainian. That is why all these bouquets of classical and modern, foreign literature I took in through the Ukrainian language. But some books in Russian were about industrial works, collective farms, and they were so boring, which is why my Ukrainian, through these translations, was better than my Russian. My Russian speaking skills were very good, but my writing skills were better in Ukrainian because the books were better. Tender Is The Night was my first book from English literature, which I read in Ukrainian, and I was 8 years old. This book is not for kids, but I was able to understand and to fall in love with this author and American Literature.

In 2014, you switched to Ukrainian as a civic duty, in solidarity. How important is showing patriotism and solidarity through language?

Solidarity is the most important thing in this world. Without solidarity, we could have never fought back Russia. Those first days of February were the days of our solidarity, solidarity between such different people, some of us who hate each other. We were not friends, but we became friends. We became people who needed to be together, to be in union, in community. And those days, Ukrainian language started to sound as a language of solidarity and possibility, an opportunity to fight back, to survive. That is why, from those days, it’s not only about security and freedom, but both. The Ukrainian language became a mechanism of resilience. And the best of the best jokes–black jokes–were made up in Ukrainian, and we are proud of our skills to make funny, some very sad and very awful things. Only the Ukrainian language gave us an opportunity to coerce Russia and the Kremlin.

I understood that I was writing in Ukrainian, because I couldn’t write about our war in the language of our enemy. And it was, literally, so simple for me, and I thought, yes, it is an idea. It is an idea about our choice and why we must do it, why we must choose Ukrainian, and how we can transcend from Russia to Ukrainian.

In Cecil the Lion Had to Die, why did you switch to fiction? Do you think it allowed you more space to present reality, allowing you to accomplish something nonfiction wouldn’t?

As a historian, I should be serious, strict. I should work with facts, documents. I should verify it. I should be honest and objective. Something like scientific freedom is very good, but scientific freedom in history requires very strong discipline and very clear frame, methodology, archival source, and so that is why, when I need to be a disciplined person, I work with my historian monographs. But when I would like to take some fantasy, some relief, some humor, I start to write my fiction.

Cecil the Lion Had to Die is written in both Russian and Ukrainian and the distinction is made so wonderfully with different colored pages – black page background for Russian and white for Ukrainian. What was the thought process behind this?

Cecil The Lion Had To Die is a story about four families from 1986 to 2020 and I started to write it in Russian. Because never, ever in Ukraine was Russian language forbidden. It’s absolutely normal to be a Russian speaker and to write in Russian. It was, and it is, only the question of choice – no restrictions, no punishments. I started to write it in Russian. Then my third, fourth episode was about some case on the front line. I was writing one paragraph, two, three, and when I had reread my fourth paragraph, I understood that I was writing in Ukrainian, because I couldn’t write about our war in the language of our enemy. And it was, literally, so simple for me, and I thought, yes, it is an idea. It is an idea about our choice and why we must do it, why we must choose Ukrainian, and how we can transcend from Russia to Ukrainian. That is why, for most of our Ukrainian readers, this way was absolutely understandable, because it is about us, it is about how we dealt with this situation. But how to show this transition to the American readers? That was a question, and that was the idea of Oleh Kotsyuba at Harvard, and he proposed to make Russian language pages black pages, and Ukrainian pages as white pages. I think it was a priceless decision. I’m so proud, and I’m so glad to see how many white pages are in my book.

As a historian, how has looking at events through a historical lens shaped your writing?

My historical lenses helped me understand that our world, our civilized world, our humanity, does not want to teach and learn lessons from history. Because right now, I understand all this story as the very beginning of World War II repeating. We can see how good people, good politicians, allow Putin to do what he wants to do, not only Putin, but North Korea. We have a union between two dictators, but we had a very similar situation in the ‘30s. I’m very scared and I’m worried because our world is very fragile. This is not a joke. This is a plan. As a historian, I am disappointed. If they were my students, they would have very small grades.

Has war stifled free expression in Ukraine and what are some of the ways PEN Ukraine is fighting back?

Ukraine is a free country, and freedom of speech is a principle of our life, of our reality. And yes, we are arguing about some problems connected with our government or with our president right now. Some of us don’t like some decisions of the government, and some of us support it, and it’s absolutely free. You can read it in the newspaper. You can hear it from TV journalists. That is why I think that censorship sometimes would be better, because our enemy can hear, can listen to our discussions and can use it against us. But Ukraine is a democracy. That is why the principle of freedom of speech is the main principle of our reality, and we must support it, and we support it.

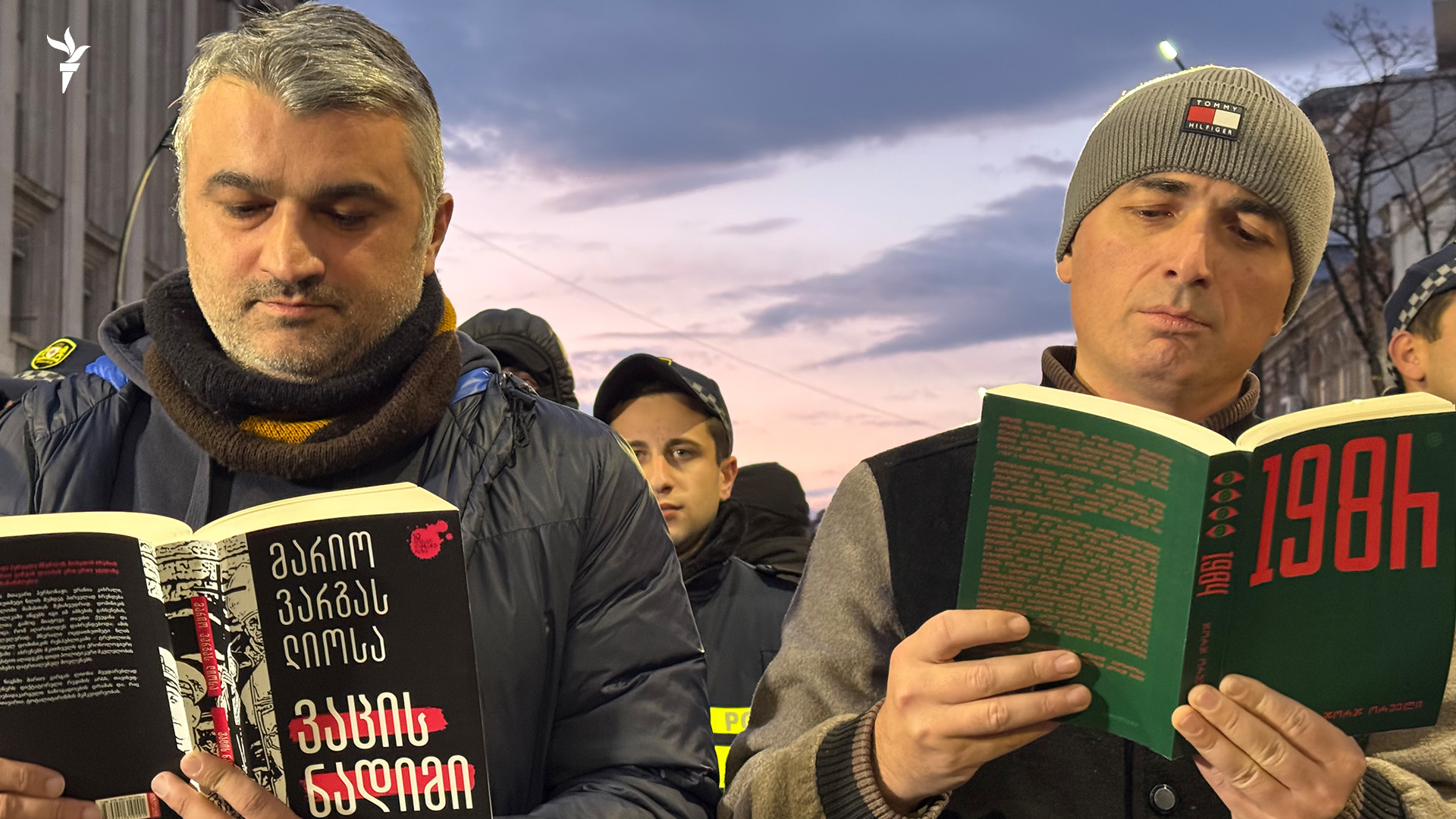

PEN Ukraine is an absolutely amazing non-government organization, and I know that we are very grateful to PEN America for support and partnership. This partnership gives us the opportunity to deliver books to the library, to the frontline, to the soldiers. And we have many common projects, and we really appreciate it. We need it, because these books for frontline libraries are not only about libraries or reading, it’s about the future–when a person can go to the library and get a book and start to read. It means that we have our Ukrainian future near the front line.

I’m trying to report, to collect stories from different locations, from the frontline, from volunteer centers, from abroad, and from America. And from shelters, from the basement, from humanitarian centers. And I think that I should give voice to all my neighbors, all my friends, and to all my colleagues.

In the beginning of Ukraine War Love, you mention how the work would be truly complete with the line, “Ukraine is victorious.” What goes into writing a book when you know the ending, but cannot write it yet?

Yes, this book has no ending, because we need a victory for a period–a huge black and yellow and blue period in my book. And in the books of my friends. We want to do it so much. And I don’t know if I wanted to translate this book into Ukrainian, but after victory, I will think about it.

You also mention with the latest aggression in 2022, you are keeping another diary. This time in Kyiv, Ukraine. Are you noticing any differences in this and that?

Yes, from 2022, every day I write it, and every day I hate myself because I gave myself work, I promised to do it every day, because if I didn’t do it, it would be a defeat. I’m happy to do it because we need to understand not only ourselves, but you and the American people, the English people, Finnish people, Spanish people. What does it mean to be at war with Russia? What does it mean to be under threat of wiping out our cities and our countries? And Ukrainian is not a new language for me, that is why it’s absolutely easier. I’m trying to report, to collect stories from different locations, from the frontline, from volunteer centers, from abroad, and from America. And from shelters, from the basement, from humanitarian centers. And I think that I should give voice to all my neighbors, all my friends, and to all my colleagues. Maybe it’s for me. I need it, not them. The voice will be with me after this war, after our victory.

And finally, are there any books you would recommend by other Ukrainian writers?

I recommend the book by Victoria Amelina. She is an absolutely brilliant writer. She was killed by the Russians in Kramatorsk in 2023. She was a volunteer, she was a poet, she was a journalist, she was an amazing person, and I know that her book (Looking at Women, Looking at War) will be published in English, and I highly recommend reading this book and to remember our brilliant writer.

This post previously stated the U.S. publisher as Harvard University Press. It is the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.