Tommy Trantino on Perseverance and Protest

I was introduced to Tommy Trantino in a 2020 undergraduate capstone seminar, “Life Sentences: Literature of the Prison,” in The College of New Jersey’s Department of English. The seminar was primarily centered on memoirs and other autobiographical works written by system-impacted people, and explored the intersections of emancipatory writing and the injustices plaguing the legal system in the United States. Each student in the class had to research and create a presentation on one specific text from the syllabus. My professor, before the semester even began, assigned me Tommy’s memoir, Lock the Lock (Knopf, 1974), and it has been an unexpected, special journey for the three of us ever since.

I was captivated by Tommy’s story from the very beginning. Born in 1938 to a Jewish mother and Sicilian father on Cherry Street in Manhattan’s lower East Side, Tommy grew up in a tenement apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where he experienced the crushing effects of poverty. He was surrounded by brutality, oppression, despair, and suffering, and struggled to find his place in this world. Dismissed and neglected in school and by the people around him, Tommy turned to the streets, where he found acceptance in the neighborhood gangs. At age 14, he used heroin for the first time and began to commit robberies to sustain his emerging addiction. Four years later, Tommy was charged for an unarmed robbery and sentenced to 10 years in New York’s Comstock Prison.

At Comstock, Tommy grew furious with the violence and inhumanity of prison life. He turned to literature as an outlet of escape, and read everything he could get his hands on: Shakespeare, e.e. cummings, Freud, Tolstoy, Joyce, Wordsworth. These books breathed life into Tommy, and he became enthralled by the language and ideas between their spines. After six years at Comstock, Tommy returned to the streets of Brooklyn with nowhere to go. He still felt lost in the world.

His addiction to heroin evolved into alcoholism, with almost daily black outs. In the summer of 1963, Tommy met up with some of the men he was introduced to in Comstock, and continued to rob people to support his addiction. When two New Jersey policemen were fatally shot at a bar in New Jersey, Tommy was convicted of the murders. On February 28, 1963, he was sentenced to death.

The Death House at Trenton State Prison is what Tommy describes as a “living nightmare.” His 6’x9’ cell had only an army cot, a cardboard shelf, and a combination sink and toilet bowl. Rats would emerge from the toilet, mice would run around the cell, and dirt and grime covered the cracked concrete walls and floors. Except for the 60-watt light bulbs that hung from wires outside of the death cells, there were no windows or light fixtures. This is where Tommy had to remain for twenty-four hours everyday until the state of New Jersey killed him–– his cell only 100 feet away from the execution chamber.

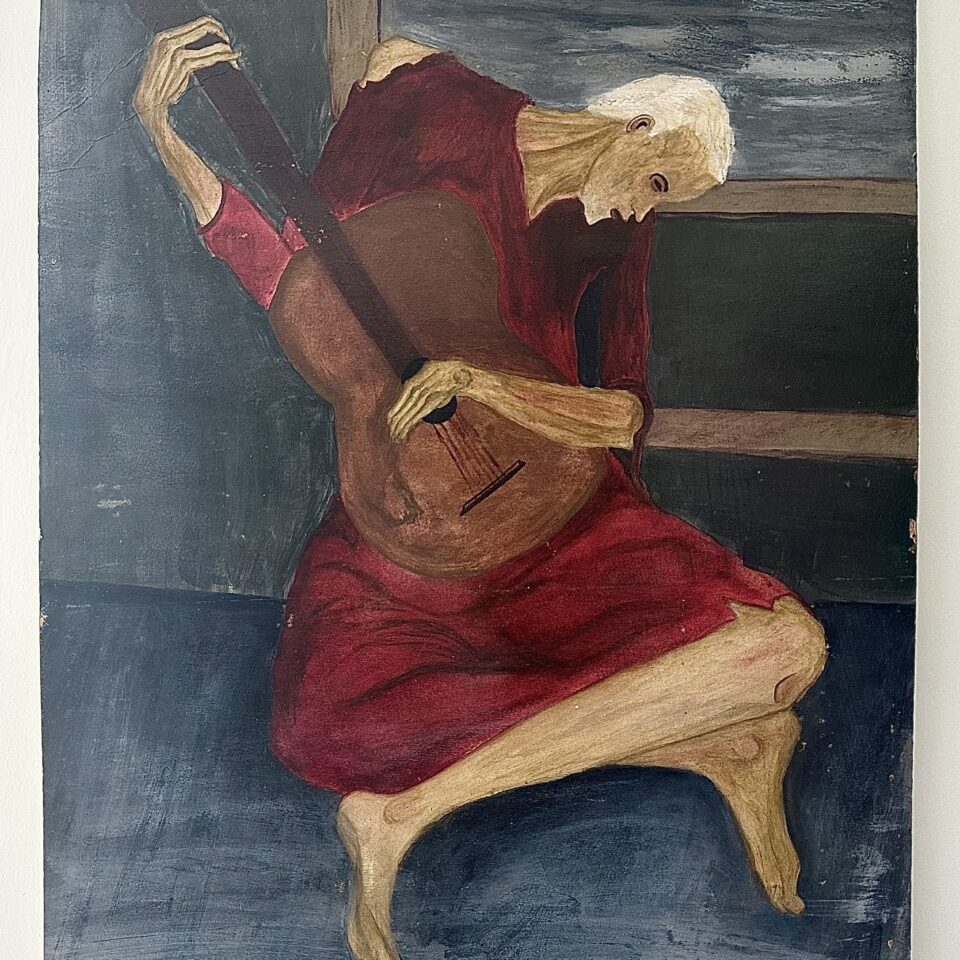

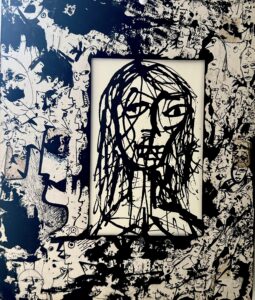

On his first day in the Death House, Tommy vowed to change his life by helping people and not hurting them, and abstaining from drugs and alcohol. With the guidance of Old Man Jack, one of the guards assigned to the Death Row unit, Tommy learned the meaning of perseverance. From this, he developed a revolutionary spirit, becoming an outspoken advocate against racism, brutality, and other forms of injustice. After leading a hunger strike with other men in the Death House to better their living conditions, Tommy was briefly placed in solitary confinement. While locked in, he stared at the shadows and cracks in the walls, and translated the shapes he saw into artwork. He began painting and drawing with any materials he could find, and quickly discovered the healing and freeing power of creativity. Deprived of light, color, connectedness, and humanity, Tommy used his pens, canvas, and acrylic paints to cultivate a world that transcended his reality behind bars. It was here in the Death House where Tommy found life and liberation.

In 1973, Alfred A. Knopf published Lock the Lock, a compilation of poems, prose, and visual art that Tommy created during his years in the Death House. The work was published completely unedited, and received international acclaim with the support of activist Abbie Hoffman and Tommy’s loved ones. His artwork was also featured in many galleries, including shows in France, Japan, and New York City. With increasing support from the outside, Tommy soon had an army of people from all walks of life, such as Howard Zinn, Kurt Vonnegut, Malcolm Boyd, Joyce Carol Oates, Woody Allen, and John Lennon, who sympathized with his plight and advocated for this release.

Tommy’s initial sentence was commuted once the Supreme Court ruled the death penalty unconstitutional in the early 1970s, and he was moved to the general prison population to serve a life sentence. He spent the next several decades in facilities across New Jersey, and continued to catalyze meaningful change from inside the prison walls. Alongside Rubin “Hurricane” Carter and other incarcerated men, Tommy organized protests and established several successful programs that provided people inside with outlets of education, healing, and growth. Tommy also continued to create— his artwork reflected his spiritual transformation and his fervent fight to live despite the bleakness and desolation of prison life. For the first time in eight years, Tommy felt the sun soak into his skin, saw the moon glowing in the night sky, smelt the trees and grass outdoors, and watched birds fly above him. These feelings and images became motifs in his drawings and paintings, his artwork opening to life as did his spirit. As he wrote in a poem featured in his memoir:

PEOPLE WHO ARE ISOLATED AND OPPRESSED CREATE

FIRST BECAUSE THEY HAVE TO

AND SECOND BECAUSE THEY MUST

PEOPLE WHO ARE DEPRESSED AND INHIBITED CREATE

BECAUSE THEY DO NOT THINK AS MUCH AS THEY FEEL

CREATION IS NOT A RATIOCINATIVE PROCESS

PEOPLE CREATE BECAUSE THEY FEEL WHAT EVERYONE

ELSE IS THINKING

AT LEAST THAT’S WHAT I THINK

After 12 parole hearings and nearly 40 years of imprisonment––the longest anyone has ever served in the state of New Jersey at the time––Tommy was officially paroled on February 11, 2002: his birthday. On the outside, he continued to work towards building a better world for himself and people around him, participating in several speaking engagements at universities, working on homeless outreach with the Volunteers of America, and founding a reentry program with the Quakers, where he became lifelong friends with my professor, Dr. Michele Lise Tarter. In the summer of 2022, Dr. Tarter called me and asked if I would like to visit Tommy with her. I eagerly agreed, and couldn’t wait to officially meet Tommy in person for the first time.

When I walked through the door, I instantly noticed the artwork that fills Tommy’s apartment. His walls are adorned with the paintings and drawings he made during his incarceration and upon his release, and there are piles of additional artwork, short stories, and poems that Tommy has produced over the years. We decided to work on creative projects together, and I have since been visiting Tommy every week. We spend hours listening to music, writing, drawing, laughing, and sharing joy in each other’s company. He always offers me deep, insightful wisdom, and truly inspires me to become a better person each day.

From the darkness of the Death House, Tommy Trantino emerged as a beam of light, continually encouraging me and those around him to have faith, persevere, and never stop working towards our collective liberation.

Jess Abolafia and Malcolm Tariq, senior manager of editorial projects for PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, speak with Tommy Trantino about his time organizing inside prison, how he started making art, and the production of Lock the Lock.

Jess Abolafia is the Prison and Justice Writing Program Assistant at PEN America. She graduated summa cum laude with a BA in English and African-American Studies from The College of New Jersey, where she also received an MA in English. Abolafia has instructed a writing-workshop at the only women’s maximum-security prison in New Jersey, empowering incarcerated women to use writing as a tool of healing and liberation. She is also working on several book projects with system-impacted individuals, including co-editing the memoir of an incarcerated woman sentenced to life in prison as a teenager, and compiling the paintings, drawings, and poems of an artist who found freedom through his artwork during nearly four decades of incarceration, including eight years on Death Row.