from Thirteen Months of Sunrise

PEN America is thrilled to showcase the work of recipients of the 2017 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grants. For the next few weeks, we’ll feature excerpts from the winning projects introduced by the translators themselves. The fund awards grants of $2,000–$4,000 to promote the publication and reception of translated world literature in English.

Today we feature an excerpt from Elisabeth Jaquette’s grant-winning translation from the Arabic of the 2009 short story collection Thirteen Months of Sunrise by author, journalist, and activist Rania Mamoun—possibly the first collection by a Sudanese woman to be fully translated into English.

Jaquette writes: I was first introduced to Rania Mamoun’s work through a short story, “Passing,” which Raphael Cormack and Max Shmookler commissioned me to translate for The Book of Khartoum (Comma Press, 2016). Although I came to the story by happenstance, I was immediately captivated by the atmospheric, emotional intimacy that Mamoun conjures so effortlessly, and sought out the full collection.

In her slim but powerful Thirteen Months of Sunrise, Rania Mamoun inhabits a myriad of voices. Over an impressive array of literary styles, common themes and characters float to the surface: the death of a father, the sense of urban alienation, and struggles of daily life in Sudan.

I was drawn to working with Mamoun not only for her writing but for who she is as a person: a fearless journalist and activist. The news that I had been awarded a PEN/Heim grant to translate Thirteen Months of Sunrise arrived the day before President Trump released his executive order banning people from seven Muslim-majority countries, including Sudan, where Mamoun lives with her family. The news cast this project in a different light. My correspondence with Mamoun shifted from inquiries over linguistic intricacies to concern for her safety and lack of freedom of movement. My role shifted from purely literary translator to an intermediary between her and agencies poised to help. In that, I am incredibly grateful for the assistance that PEN America has provided.

I believe that providing a platform for Mamoun and authors like her is even more important in a time when the United States is shutting its borders and stoking racist xenophobia. Yet work like hers should not be forced to exist in a space defined primarily by the narrative of security. Ultimately, I hope that readers seek out her prose for its playful and experimental take on literary techniques.

“The heart disavows borders and pays no heed to distance,” Mamoun wrote in correspondence recently. The same can be said, I believe, for literature through translation.

*

Steps Astray

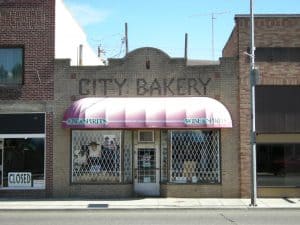

I hadn’t intended to go just as far as my strength could take me, just two streets from home. I meant to go beg from the bakery on the next street over.

My crippling hunger set me in motion. I was so hungry I couldn’t do anything, not even sleep. I rallied myself and pushed past it to go out, dreaming about bread, even just a single stale piece. I usually beg from the bakery workers, and they usually give me what I want and take what they want. Some of them buy me falafel from the woman who sells it fresh in front of the bakery, hot and delicious, so I’ll stop my howling. I know what they want from how much falafel and bread they give me. I don’t care how they take my body; they don’t have much desire for it anyways. What can this skinny, tired, and sickly body give them? What flames can it quench?

The bakery was closed when I got there, maybe because of electricity problems. That happens often. It explained why I didn’t hear the metallic squeal of trays as they happily went in and out of the oven, carrying heat and life for me and people like me. We see life in these round, tan pieces of bread. They look like paintings, with random progressions of colors because the heat isn’t even, from white to brown to beige all the way to black, where they’re burnt in different places. When we get hold of these circles, we feel like we’re holding a piece of heaven.

The bakery was shut in my face and that meant my hunger would go on and I’d go into sugar shock. I didn’t know when I’d wake up. Maybe I wouldn’t wake up. I thought about this, standing in front of the huge iron door barring everything inside, including my elixir of life.

I stood there quietly that night and asked myself: What was the solution? Go back, or wait out my fate here? What was the point of going home, where there was nothing but tap water and my mother, whom I only like sometimes when I have all my wits about me, while she just has half her wits, or maybe a quarter? They disappear and reappear at random, only her mind knows when they’ll be there or when they’ll be gone.

If I went back for tap water, it would fill me like a waterskin, and my hunger wouldn’t quiet down and I’d have to pee much more than I already do, which is already more often than I can count. Since I don’t know what comes after ten—maybe a hundred or thirty—I don’t know for sure. I make lots of mistakes counting from nine to eight. I know one comes after the other, but I don’t know which is first; whatever my tongue says first I figure comes first, and my tongue does what it wants; sometimes it likes nine and other times eight, and usually I don’t use counting except for when I’m counting the number of pieces of bread I’ve wolfed down in a week, which is rarely more than ten. So I don’t count past that, and that one week I was always full, because that week there was also falafel and leftovers from our neighbor the doctor, who’s traveling now.

Tap water wasn’t a good enough reason to go home, so I had to knock on doors, which is what my uncle forbade me from doing. He beat me when he found out I’d knocked on one of his friends’ doors, and told me, “You’re disgracing us.”

He doesn’t want me knocking on doors in our neighborhood or the next one over, but he doesn’t have a problem with neighborhoods further away. He shared what I got and gave me advice not to waste effort knocking on doors that are rusty or battered or unpainted or open.

My uncle works as a driver for one of the institutes, but he also has a job as a first-class drunk, so what he does with his salary won’t help me.

I didn’t care that my uncle was afraid of me disgracing us. The snake coiled inside me was hissing louder with every passing minute, and if I didn’t toss it some prey, it would devour me.

Just then I heard the sound of a celebration from far away. I listened harder and the sound got clearer and I wondered: Is it a wedding? But it wasn’t Friday. As far as I knew and understood and had seen, Friday was the day for weddings. Every Friday I caught a whiff of weddings being celebrated in houses with wide open doors. They were the only ones my uncle told me to go into without asking permission; he told me I’d be sure to leave with a warm belly and a smile on my face. He was right. I always left different to how I’d arrived, even if I’d just eaten what was left on the plates, which was what I usually did.

There aren’t weddings on Mondays. What was it?

I remember what my friend—who also goes trawling at celebrations—said two days ago, that sometimes there are birthday parties, but she didn’t tell me when. Maybe there’s one today. Whatever the reason for the party was, I was going to follow the sound and find something to keep me alive until tomorrow.

I walked a few steps before I felt my hands start to tremble. I thought about what I could get by begging, or even stealing.

I needed to eat and I needed something with sugar. The shaking had started and was getting worse.

I sped up and the road seemed endlessly long even though it was just one street. Would I make it?

I found out a moment later, when everything crumbled and I collapsed on the ground. I didn’t lose consciousness, but I couldn’t get up and start walking again.

I lay there for several minutes, or maybe hours. I lost hope of getting my strength back, even just a bit of it, even enough to get to the house with the party. I heard a car go by and realized that it would be dangerous to stay where I was until morning. My flesh and bones and blood would be ground into the dirt.

I gathered my strength … crawled slowly … slowly I crawled … My knees got scraped, and the little rocks and pieces of dirt pressing into my elbows hurt. I needed to be careful because even a small cut could lead to losing a limb.

I crawled to the closest house, one on the corner. In front was a big rock and a mazeera with three water urns. I sat up and leaned against the big rock. I couldn’t make it to the mazeera to take a gulp of water, and I couldn’t make it to the door to knock on it, so I just huddled there.

My strength deserted me like my father deserted me when he fled to the other world. I don’t know where he lives now, like my mother deserted me by fleeing to her own world, nodding off there and strolling through the green gardens and red underworld. My poor mother who couldn’t bear my father’s absence; the moment his body entered the grave, her mind flew into the air and its cells scattered and its particles got all mixed up. My strength deserted me like my uncle deserted me like my body deserted me, defeated by its damned diabetes.

A dog started to bark, followed by another. They were coming toward me. They must have thought I was a dead body or something else they could eat. The street was empty and quiet. I didn’t know what time it was, but I was sure no one was awake except me and these dogs whose numbers were rising, and those dancers at the party.

Every cell in my body was shaking. I grabbed a handful of dirt and swallowed it. The dogs amassed around me … barking … getting closer … One of them took a long look at me and came up really close. It was the dog that belonged to our neighbor, the doctor. He sniffed me, looked into my eyes, and I thought that he recognized me. He nudged me with his hand, or his foot, I don’t know what to call it because he walks on all four and I don’t know whether it’s a hand or a foot.

When the dogs began to come closer and their barking grew softer, the one dog turned to them and must have told them something because then they retreated a little and went completely quiet.