Born shortly after World War I, when writers were seeking ways to build bridges among people, what is now known as PEN International began as P.E.N., a dining club of Poets, Essayists, and Novelists who would soon discover they rarely agreed on anything.

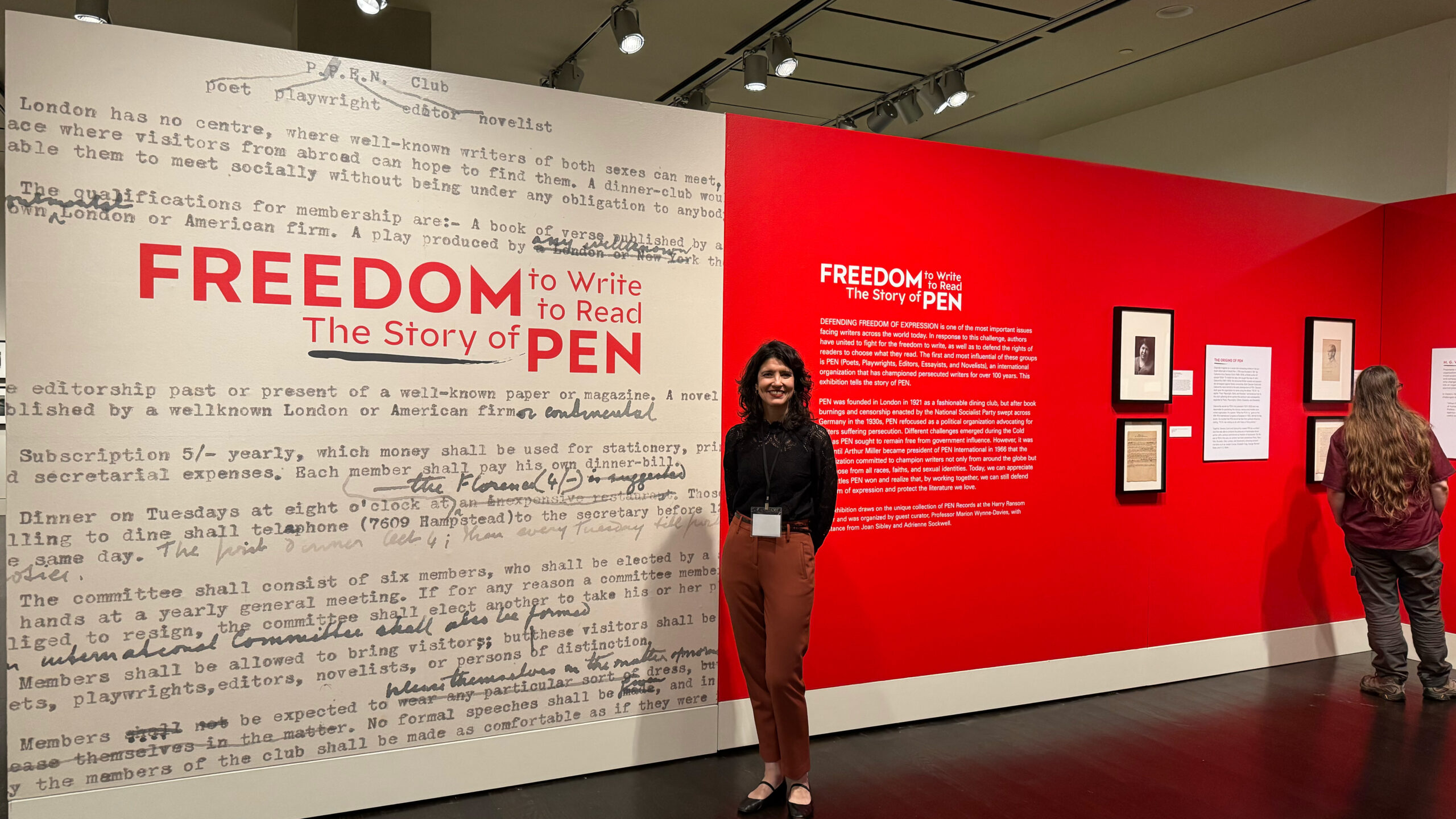

PEN’s history is one of debate, and a new exhibit – Freedom to Write, Freedom to Read: The Story of PEN, on display at the Harry Ransom Center in the University of Texas at Austin through Aug. 18, 2025 – highlights key moments that shaped the organization’s history and unwavering support of free expression.

The exhibit brought to mind “the ways in which our current moment echoes so many other moments in history,” PEN America Interim Co-CEO Summer Lopez said at the Harry Ransom Center’s Flair Symposium.

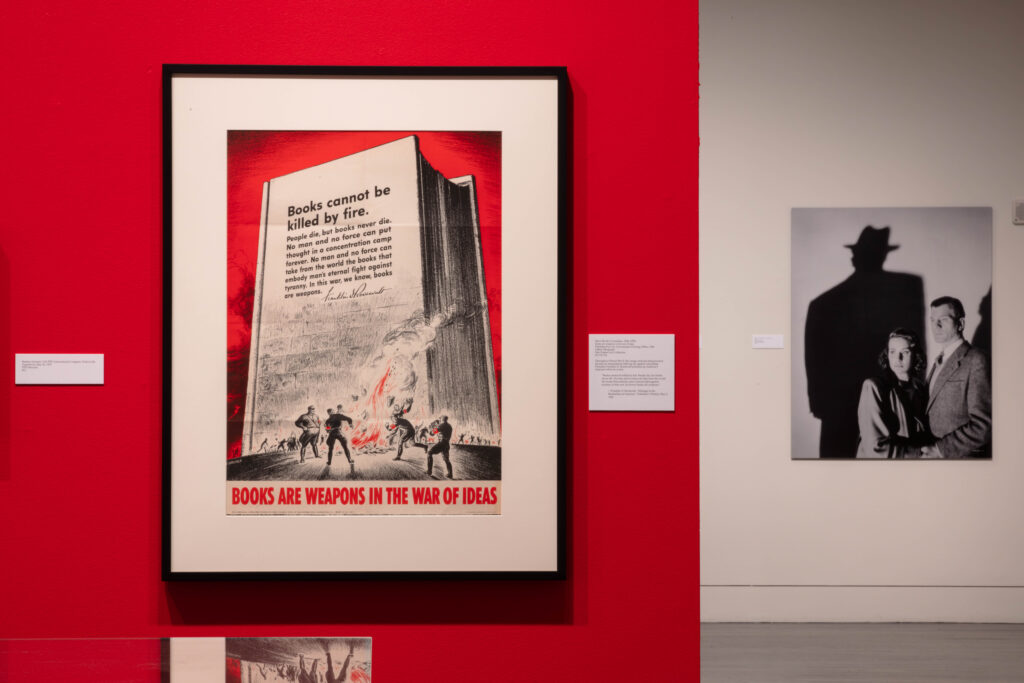

A 1942 poster in the exhibit that said, “Books are weapons in the war of ideas” reminded her of remarks by Salman Rushdie at an emergency writers’ congress PEN America hosted in 2022. “He said, ‘A poem cannot stop a bullet. A novel can’t defuse a bomb. But we are not helpless … We can sing the truth and name the liars. Stories are at the heart of what’s happening … we must work to overturn the false narrative of tyrants … by telling better stories.’”

“‘Stories are at the heart of what’s happening.’ I really believe that,” Lopez said. “Stories have power – they allow us to see hard truths, and to imagine what is possible. … That’s why they are so often attacked, twisted, and yes, banned.”

The exhibition explores key moments in PEN’s history, such as its opposition to the Nazi book burnings in the 1930s. Founding President John Galsworthy had insisted that the organization be free from political influence. The wave of Nazi censorship caused a break with the Nazi P.E.N. Club of Berlin – and transformed PEN from a social club into a political organization advocating for writers suffering persecution.

PEN began campaigning for the release of imprisoned writers in 1960, establishing the Writers in Prison Committee the following year and the Day of the Imprisoned Writer in 1981 to raise awareness of writers jailed for their views. It began including an “Empty Chair” in PEN meetings as a reminder of writers who could not be present.

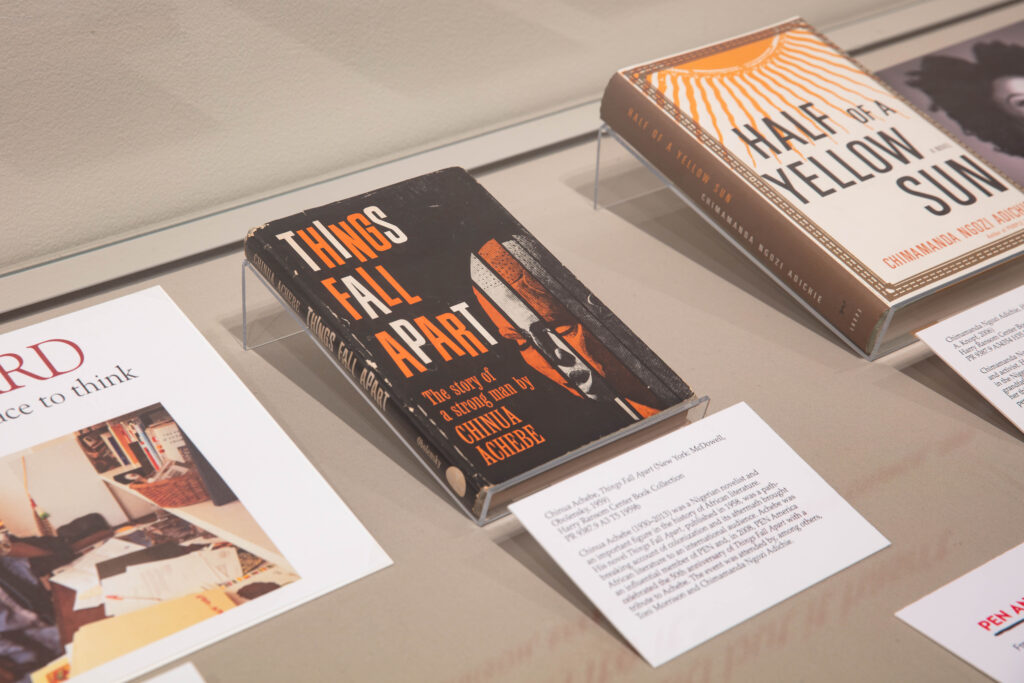

The exhibition displays books banned throughout history and celebrates prominent PEN leaders and Members, including Rushdie, Arthur Miller, Toni Morrison, and Margaret Atwood. It highlights the organization’s advocacy on behalf of women, writers who have been persecuted for their religious beliefs and frequently censored LGBTQ+ authors.

It’s a history that’s now all too present – as PEN America’s latest research documented more than 10,000 book bans in the last school year alone. Lopez moderated a panel on “Banned Books and Novel Ideas” at the Flair Symposium, with Dr. Julia Mickenberg and Dr. Heather Houser of the University of Texas at Austin and Cindy Hohl, president of the American Library Association.

Former PEN America President Ayad Akhtar spoke about another contemporary threat to writers – the rise of generative artificial intelligence. Akhtar, whose play McNeal on Broadway examines the use of the new technology, said his advice to young writers is “to figure out how to fall in love with what you do so deeply that you never question whether or not it’s worth the trouble.”

Although he said he has no question that A.I. is here to stay and will be part of the creative process, “it’s worth believing in a thing that many of us worry may not have as robust a future as we hope.”

“As the great Fitzgerald once wrote, ‘The test of a first rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise.’ For me, Fitzgerald isn’t just describing the kind of mind that literature creates in us. He’s also describing our task as lovers of literature in an era of advanced cognitive decay. We must face the enormous forces marshaled against what we love most, and we must be determined to make it otherwise.”