October 5, 2023

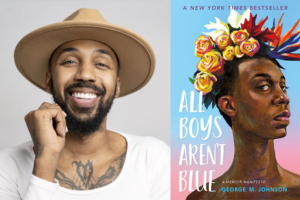

George M. Johnson’s memoir All Boys Aren’t Blue had been banned in more than two dozen school districts when the battle over the book came close to home.

In Glen Ridge, New Jersey, just miles from where Johnson grew up in Plainfield, a group called Citizens Defending Education demanded that All Boys Aren’t Blue and several other books be removed from the library. Johnson couldn’t make it to the library board meeting, but asked their family to step in.

“(George) said would you, and aunt Sarah and Aunt Munch be willing to go if I wrote a letter. And if they allow you to read the letter, would you read it?” Johnson’s mother, Kaye Johnson, told PEN America. “Of course! Because (their) book wasn’t the only one being banned. So now we got to step up for everybody. Because you’re not only attacking George, you’re attacking everybody else who just wants to tell their story.”

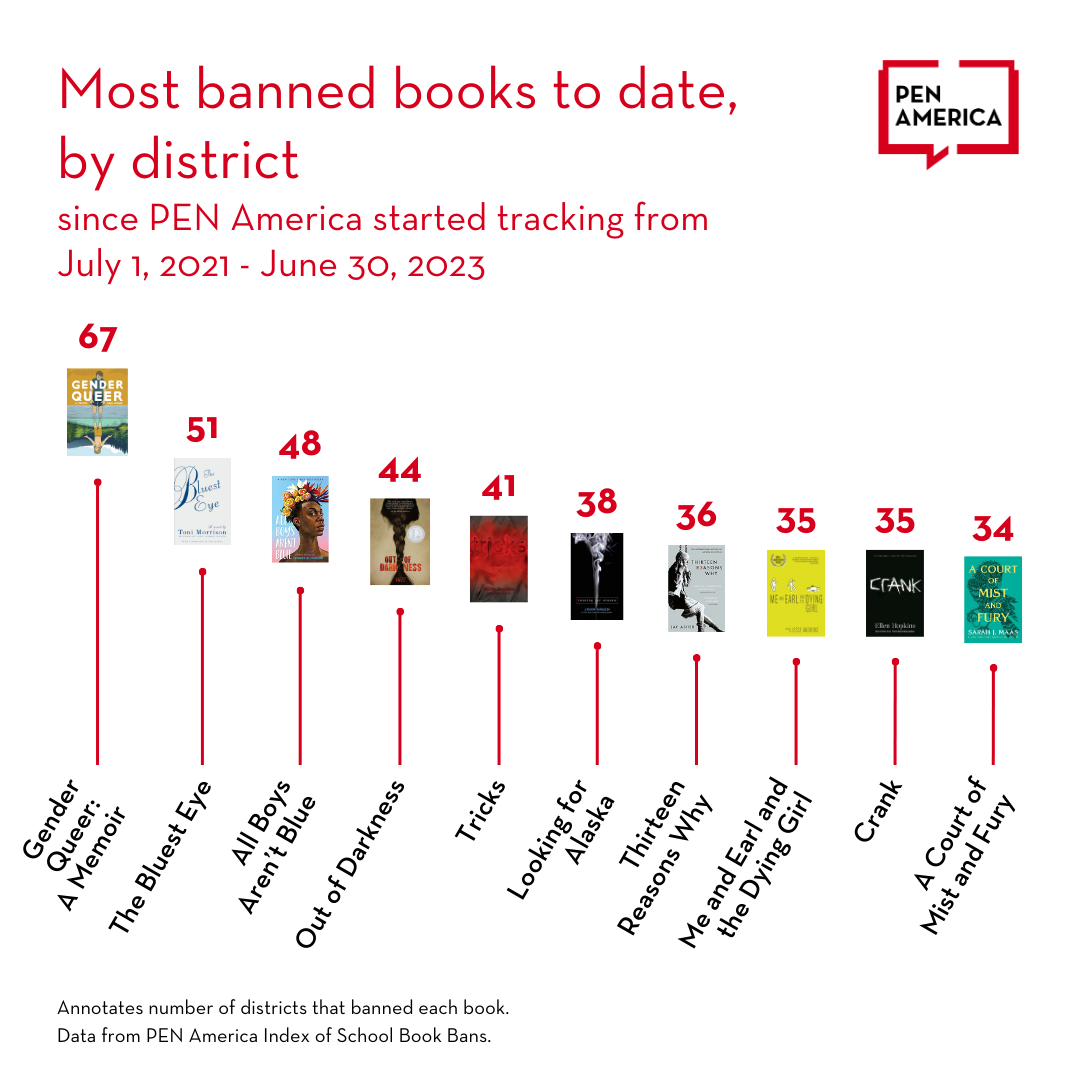

Kaye Johnson and her sisters saw challenges to All Boys Aren’t Blue as not just attacks on the book, but attacks on who George is, and the right of people like them to exist. Johnson, who uses they/them pronouns, is a plaintiff in PEN America’s lawsuit challenging book bans in Escambia County, Florida. All Boys Aren’t Blue is the third most-banned book since PEN America began tracking bans in U.S. Schools in 2021, with 48 bans.

“Of course, first reaction is where he at? What are we doing? Where we going?” said George’s aunt Sarah Elder. Stephanie Elder-Law, known as Aunt Munch, added, “Of course, I want to confront anybody who wants to publicly come out and say that my nephew doesn’t have a right to exist, or people like my nephew don’t have a right to exist.”

“Of course, I want to confront anybody who wants to publicly come out and say that my nephew doesn’t have a right to exist, or people like my nephew don’t have a right to exist.“

Going into the meeting, George M. Johnson’s mother and aunts were nervous. “I didn’t know what to expect,” Kaye Johnson said. “So now you’re looking around and you’re wondering, how far are we gonna go with this? Are we gonna get physically attacked? So then you just go on the defense, and you say, God cover us, and move forward.”

When they pulled onto the block and saw the response, they were overwhelmed. Opponents of the book ban were in the street, marching from the parking lot to the school where the meeting was held.

“To see the signs, and the police presence was kinda like, wow, like, this is major,” Sarah Elder said.

She read a letter from George, saying that the book is needed to help young people grapple with tough topics they experience every day.

“As a Black queer person, I know what it’s like to read books that don’t tell my story,” George wrote. “So in this hunt to protect teens, does it ever cross your mind that removing or restricting this life-saving story for LGBTQ students only harms them more or how removing this life-saving story for Black teens harms them? Or do you not care? That’s really what this fight is over — removing LGBTQ stories and Black stories. If you don’t want your child to read it, that’s fine, you have every right to allow your child not to read, but you don’t get to trample on the rights of parents like my mother and my aunts.”

“As a Black queer person, I know what it’s like to read books that don’t tell my story,” George wrote. “So in this hunt to protect teens, does it ever cross your mind that removing or restricting this life-saving story for LGBTQ students only harms them more or how removing this life-saving story for Black teens harms them? Or do you not care? That’s really what this fight is over — removing LGBTQ stories and Black stories. If you don’t want your child to read it, that’s fine, you have every right to allow your child not to read, but you don’t get to trample on the rights of parents like my mother and my aunts.”

The reaction was electric. The auditorium echoed with applause. After the public commentary and deliberation, the board voted to keep all All Boys Aren’t Blue and five other challenged titles on the shelves.

“I love the fact that in that small community, overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly wealthy, that those folks decided to say, Not In Our Town, that this small group of eight people are not going to tell us what we can allow our children to have access to.”

Johnson’s family felt grateful for the support. “I love the fact that in that small community, overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly wealthy, that those folks decided to say, Not In Our Town, that this small group of eight people are not going to tell us what we can allow our children to have access to,” said Stephanie Elder-Law.

They also had the chance to hear from young adults who loved the book, and adults who said it helped them start a conversation with their child.

“George knows that we love (them) so much and we are so very proud,” Sarah Elder said. “Now that we are truly as a family in this fight, we will not only continue to fight for George, but we continue to fight for all the other voices that are out there that people are trying to suppress.”

Damarcus Adisa is PEN America’s video producer. Lisa Tolin is editorial director.

Banned in the USA Spotlight: George M. Johnson

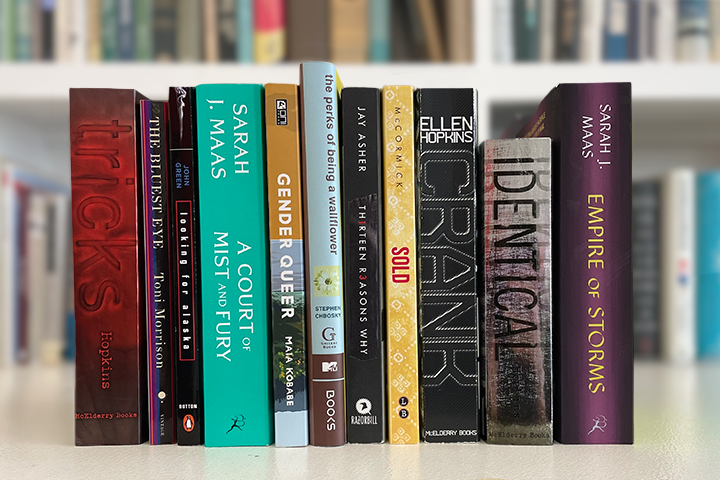

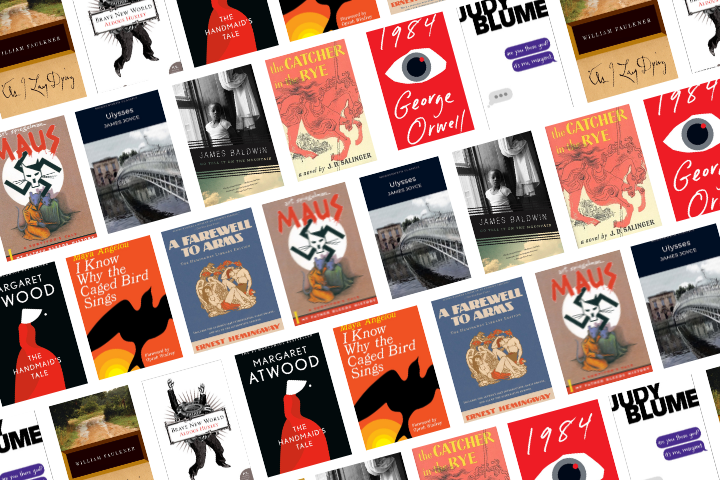

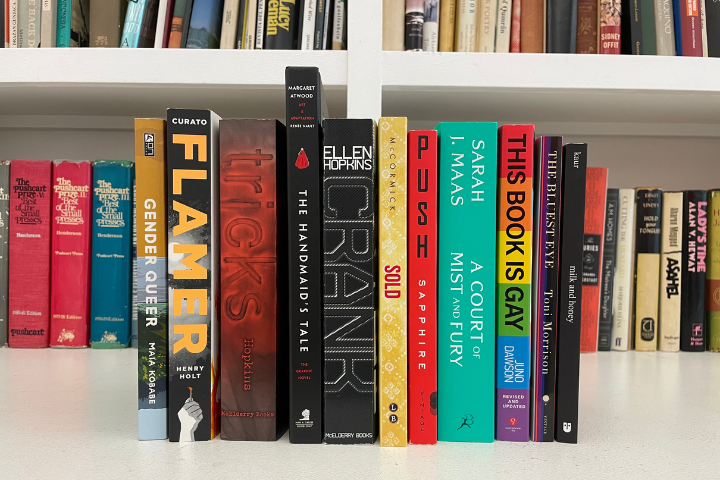

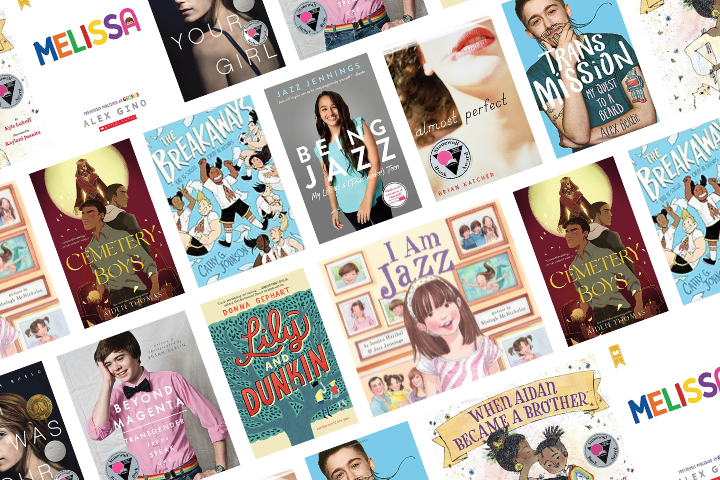

Pride Month: A Banned Book Reading List