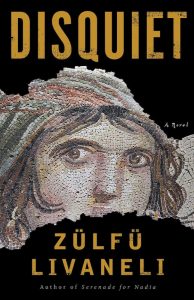

The PEN Ten: An Interview with Zülfü Livaneli

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Zülfü Livaneli, author of Disquiet: A Novel (Other Press, 2021).

Photo by Cem Talu

1. How can writers affect resistance movements?

Once, writers acted as the conscience of the people. From François Villon to Heinrich von Kleist and Omar Khayyam to Victor Hugo, they tried to trigger people’s empathy to create a better understanding between different social classes and cultures. Émile Zola’s J’accuse, for example, was one of the striking examples of engaged literature. However, in the postmodern era, literature has changed dramatically. It has disengaged from the problems of humanity.

2. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today?

There are threats from governments, fundamentalists, ideological blindness, and so-called agitprop attitude, but there is also a threat from inside. By this, I mean the literary fashions, which degrade the function of creativity to an intellectual game.

3. You’re no stranger to having your free expression challenged. How have your personal experiences with censorship affected your writing?

I’ve had a turbulent life. I was in military prison, have endured psychological torture and media lynches, my works have been banned, I spent 11 years in exile, got death threats, was forced to live under police protection to protect me from fanatic groups, etc. Not a walk in the park, of course. But all of these experiences made me realize that my work is important because totalitarian regimes are afraid of my words. This is a strange kind of satisfaction. I’ve felt that my poems and novels meant something.

“I was in military prison, have endured psychological torture and media lynches, my works have been banned, I spent 11 years in exile, got death threats, was forced to live under police protection to protect me from fanatic groups, etc. . . . But all of these experiences made me realize that my work is important because totalitarian regimes are afraid of my words. This is a strange kind of satisfaction. I’ve felt that my poems and novels meant something.”

Years ago, I participated in a writers’ gathering with my late friend, the father of modern Turkish literature, Yaşar Kemal, in New York. During his speech, Kemal gave many examples of Turkish poets and writers who had been murdered, imprisoned, and exiled for centuries. After his speech, Kurt Vonnegut approached us, congratulated him, and said, ‘’You are fortunate because authorities think you are important. Here, we are free, but nobody cares.”

They’re not always free, of course. Arthur Miller once told me that he couldn’t get a passport during the McCarthy era.

4. What is it the most daring thing you’ve put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I have no regrets about my work. I wouldn’t want to change a single word I’ve written. In one of my early poems, I criticized the cruelty of the Turkish army with harsh words because they had killed my friends. It was immediately banned, and still is today. I’ve been sentenced several times because of this poem, but I’ve never regretted it.

5. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I’m not a social realist or a naturalist writer. I create characters that don’t live in a vacuum. My characters are influenced by the environment and by political and social developments. We are all zoon politikon in Aristotle’s concept. I approach social problems through my protagonists’ psychologies.

One of the best examples of this in world literature is the Joe Christmas character in William Faulkner’s Light in August. Although the character is not aware of historical and social circumstances in the larger sense, we see the whole tragedy of the South through him.

“I have no regrets about my work. I wouldn’t want to change a single word I’ve written. In one of my early poems, I criticized the cruelty of the Turkish army with harsh words because they had killed my friends. It was immediately banned, and still is today. I’ve been sentenced several times because of this poem, but I’ve never regretted it.”

6. In Disquiet, your protagonist Ibrahim almost reverts back to a former version of himself, as he returns home to the small city of Mardin after working in Istanbul as a journalist. The smells, the sounds, and the sights trigger a host of memories he didn’t know were still held within him. Are there places that do that for you? If so, how do these places figure in your own writing?

Smells are important for remembering, sometimes more than images or words. Every country, every region has its own smell. I first noticed this when I escaped from my country to Germany using a fake passport. It was my first trip abroad. The smells in the Munich train station were strange to me. Marcel Proust’s unforgettable madeleine cookies story is based on the same feeling. He created a masterpiece around the smell and taste of cookies.

7. In a similar vein, I was really intrigued by how sociopolitical events, such as the rise of ISIS, affect the sensory details that Ibrahim experiences throughout the book. Mardin—which had once been full of aromas of food and Assyrian wine and an overall atmosphere of festivity—becomes “darkened by the shadow of a sterner, angrier Islam.” How do you approach the sort of “distilling” of these large sociopolitical events, so that they become an aroma or fleeting emotion?

7. In a similar vein, I was really intrigued by how sociopolitical events, such as the rise of ISIS, affect the sensory details that Ibrahim experiences throughout the book. Mardin—which had once been full of aromas of food and Assyrian wine and an overall atmosphere of festivity—becomes “darkened by the shadow of a sterner, angrier Islam.” How do you approach the sort of “distilling” of these large sociopolitical events, so that they become an aroma or fleeting emotion?

Unfortunately, Islamic fundamentalists draw a dark blanket over every single joy of life. They are against any kind of pleasure. If this were only a preference for themselves, that would be acceptable, but they impose their primitive understanding of life on everyone around them. In their eyes, the things that give life meaning to us, that are inspirations of creativity and the arts—like music, love, poetry, wine, dance, and laughter—are all sins.

Let me tell you about one of my observations. As a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador, I played a role in organizing a meeting with Shimon Peres and Yasser Arafat in the legendary Alhambra palace in Granada, Spain, in 1999. There was a musical performance at the palace theater with Arabic and Spanish musicians. It would be a kind of a revival of the late Andalusian mixed culture. In the first part of the concert, male North African, Magrebian musicians came to the stage and performed a wonderful but slightly monotonous and lifeless piece of music. After them, Spanish guitar players and female dancers appeared. The whole atmosphere changed in an instant. Music became more alive; passion became almost visible between the male musicians and female dancers like an erotic game. We could witness life in all its chaotic beauty. I think this was a great example of the dramatic difference between the two cultures.

“In my opinion, beliefs and truths are mutually exclusive. If you want to believe in something, you must stop thinking and questioning, and logical explanations are never enough. Questioning existence is the field of philosophy.”

8. Throughout the book, we accompany Ibrahim as he uncovers details about his childhood friend’s murder. In true reporter form, he—and, transitively, the reader too!—receives most of his intel from long anecdotes shared orally by old friends. As a result, much of the book’s exposition takes place in long stretches of dialogue, so that it reads like an oral history. So much folklore seeps into the book, but I was wondering if any specific stories or storytelling traditions inspired your writing.

The Mardin region lives with sagas and legends. People still talk about the war with Tamerlan and how the Mongolian army couldn’t conquer their castle, which took place in the 14th century. The Middle East is full of prophets, saints, miracles, and dreams. There are a lot of strange beliefs and superstitions in Mesopotamia. That kind of oral culture always helps to enrich a story.

9. Ibrahim has a particularly memorable conversation with an Assyrian priest about how beliefs that are of value to others can feel empty if they are not characterized by “truth.” Given that your characters dwell on this question throughout the book, I wanted to pose it to you as well: What are the limitations of using “truth” to assign value to beliefs?

In my opinion, beliefs and truths are mutually exclusive. If you want to believe in something, you must stop thinking and questioning, and logical explanations are never enough. Questioning existence is the field of philosophy.

10. What has been your experience of having your work translated? What is it like to see your writing printed in a different language?

I must say that it is strange and a little frightening. I write local details that are not known in other cultures. So I always wonder whether people from different cultures understand me—many different idioms, different lifestyles. Then, I think about the foreign writers that I adore. It’s a relief. If the story, the writing style, and the translation are good, it’s possible to reach most people’s hearts and minds.

An example: Surprisingly, one of my novels, Bliss, became a bestseller in China. I gave many interviews in Beijing and Shanghai, and all the journalists there said they loved the book. Some of them told me that they found elements close to Chinese reality. I was surprised and asked what these were. The answer was very interesting: They said the novel described a country (Turkey) torn between tradition and modernity, exactly like China is.

I must add that the translators are doing an important job. If the translation is not good, it’s impossible to reach these readers. Luckily, I’m a fortunate writer in that sense. I have first-class translators in English, French, German, Italian, and many other languages. I used to have bad experiences as well, but they are rare.

Zülfü Livaneli is Turkey’s bestselling author, a celebrated composer and film director, and a political activist. Widely considered one of the most important Turkish cultural figures, he is known for his novels that interweave diverse social and historical backgrounds, figures, and incidents, including the critically acclaimed Bliss (winner of the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Award), Leyla’s House, My Brother’s Story, and The Eunuch of Constantinople, which have been translated into 37 languages, won numerous international literary prizes, and been turned into movies, stage plays, and operas.