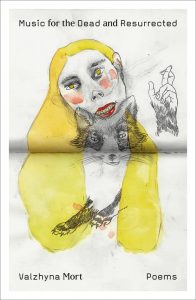

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Polina Sadovskaya speaks with Valzhyna Mort, author of Music for the Dead and Resurrected (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020).

1. Music plays a central role in your new book. I cannot help but think of the current revolution in Belarus where music is also extremely important. Closely watching this protest since the beginning, it seems to me that it is really music that managed to unite the people of Belarus like never before. For instance, people have sung Belarusian lullaby “Kupalinka” as a form of protest, and musicians have gone from neighborhood to neighborhood every night to lift the spirit of peaceful protesters. What sort of power is music for the Belarusian people right now?

Belarusian poet and musician Uladzimir Liankevich was among many people detained for singing “Kupalinka” on the street. At his trial, when asked to explain why he was singing a song—because right now, singing a song is enough of a reason to be arrested in Belarus—he said that when he sings, he is not afraid.

“Kupalinka” was written by Michas Czarot, a poet who was arrested in 1937 for “anti-governmental activity.” He wrote his last poem on the wall of his prison cell while waiting for his execution. People might not remember this, but language does remember where it comes from.

Why is the authoritarian government afraid of people singing together? Perhaps it sees singing as a training in solidarity, a training in community. The policy of our authoritarian government has always been to disenfranchise the society—to generate mistrust—which makes solidarity impossible. Singing together is an important communal exercise in trust and unity. Communal singing generates strength that’s impossible to achieve with normal speech, because in singing, we become one body with others.

Why sing at the protests? Why not stop at just chanting? Because Belarusian protests aren’t political. They are a people being born as one community for the first time in 250 years. So, it is indeed a lullaby for a newborn nation.

“Why sing at the protests? Why not stop at just chanting?Because Belarusian protests aren’t political. They are a people being born as one community for the first time in 250 years.”

2. Many of the poems in your book sing as well, and there is even your own lullaby. What sort of power is music for you?

Music for the Dead and Resurrected explores the connection between music and trauma. Many people think of music as something ambiguous, but for me, it’s the opposite. Music tells us precisely what words fail to say. I love the way Felix Mendelssohn puts it: “What the music I love expresses to me are thoughts not to indefinite for words, but rather too definite.”

I walk through the fog of memory, through the fog of imagination, from non-history, from the darkness of the self, toward clarity. And for that, I need a supreme language—which, for me, is music. What is music? Sounds, available to all of us, arranged in a pattern of themes, variations, and repetitions. This pattern is utter magic. Word order in a poem is the same magic. This order creates a space we experience by walking from word to word, from one stanza/room to another. Unlike architects, poets build solely in the air, with breath. It’s a space of reverie we have to create because our physical spaces are not enough. Our hearts are multidimensional.

I spent my childhood in the kitchen, listening to my grandmother’s stories of survival. And the radio was always on—it had to be on because she thought of a radio as a source of emergency information: Wars are announced on the radio. But the war was over, and the radio played Bach, Scriabin, Grieg, Mozart, and gradually, I grew to associate these composers with my grandmother’s voice, with the stories of Belarusian survival. Gradually, I’ve also realized how much this music helped me to cope with my grandmother’s stories.

“Many people think of music as something ambiguous, but for me, it’s the opposite. Music tells us precisely what words fail to say. . . [It’s] sounds, available to all of us, arranged in a pattern of themes, variations, and repetitions. This pattern is utter magic. Word order in a poem is the same magic. This order creates a space we experience by walking from word to word, from one stanza/room to another.”

3. Back to writers and their role in the resistance movement. How can writers in modern Belarus affect change? Can you name a few writers who are doing so?

When Uladzimir Liankevich was arrested with Hanna Komar for singing in the street, people started saying, “The police is going after poets now!” But Uladz wanted everybody to understand that he was arrested not because he was an artist. He was arrested because anybody walking freely in the streets can be arrested. Poet Dmitry Strotsev is in jail for two weeks because he was photographed on the street showing a victory sign with his fingers. Before that, he had never missed a protest, and every week, he’d post new poems—short, poignant lyrics that try to make sense of the Belarusians reality.

Let’s remember that in Poland, Anna Swir waited for 30 years to write her short, record-keeping poems that resemble small photographic squares of the occupied Warsaw. Both timeframes are valid. A poet doesn’t have to be relevant to the moment, yet they always are.

The lyrical voice is the voice that says, “There is still so much to understand.” It also says, “It’s okay to lose control of your heart.” Our state said, “You have your food and bed, what else do you want?” And the people answered from the streets by quoting from poet Yanka Kupala: “To be called people.” It’s a poem first published in 1908. A call and response, some say it has the rhythm of a marching and chanting crowd. I agree. But I have also recited it to myself many times these days, in moments of defeat and fear, and I discovered that this poem is not only for the marches. It’s also for the prayer after you return from the march into a dark apartment and find yourself, after the exultation of solidarity, alone and broken.

“Belarusian bones are unburied bones. Walking in those woods, one finds personal objects with inscriptions scratched upon them—words speaking to us, the living. Belarusian bones are speaking bones. Belarusian bones are also scattered bones—there was so much forced dislocation, from World War I to the Soviet Labor camps. A bone is indeed ‘a key to my motherland.’ A bone is also an answer to the question, ‘Where am I from?’”

4. Belarus is—or was until recently—that place which I can call, in your own words, a place “known for being unknown.” For many people in this part of the world, it is hard to explain the Belarusian narrative. For some, it’s even hard to identify Belarus on a map. In your book, there is the repeated question: “Where am I from?” Is this how you feel? Is it that this constant denial of your birthplace by the West makes you also question its existence?

We are the Wakanda of Europe, aren’t we? The gaze of this question is my own. I spent 1/3 of my life with my grandmother sitting me down in the kitchen and telling me the stories of loss and survival in the Stalinist ’30s, during World War II, in the post-war Soviet Belarus. In school, I sat in history classes wondering why the stories of my family had no place in official narratives. I sat in literature classes, my mind wandering through the streets of Moscow and St. Petersburg following the characters of Dostoyevsky or Chekhov. But never Minsk. I was four when a nuclear accident at reactor No. 4 caused the Chernobyl disaster. Seventy percent of the radiation fell on Belarus. Words like “zone” and “cesium” entered our everyday vocabulary. Chernobyl acquired a fairy-tale quality in my childish imagination. I learned to see the invisible—radiation—in every apple, every tree leaf. We, kids, told stories of horrible monsters birthed by Belarusian mothers.

I was 10 when the Soviet Union officially dissolved—yet its collapse is ongoing, taking decades and generations to arrive and reach its completion. I came of age at the time when Belarus started to exist as an independent country, yet my parents were very Soviet people and struggled to start their lives anew. My grandmother, my intimate interlocutor, felt great love for Stalin. I used to ask her, “But why, grandma? Every single sad story you tell, Stalin is responsible for it.” She would get mad at me for saying such things, and I stopped. Instead, I asked, “Where am I from?”

5. There is a line in the book that describes Belarus: “A bone is a key to my motherland.” This line made me think of how not too many people actually understand the strength of Belarusian people. For many, it is hard to understand how it is possible to see your loved ones being fired, threatened, arrested, and even tortured, and then continue going to the streets with flowers, songs, and funny protest signs. What kind of bones are these—Belarusian bones?

Belarusian bones are restless bones. Bones of mass graves, bones picked up from the ground by the living. Many poems in the book speak about Kurapaty, a wooded area on the outskirts of Minsk where many great people were executed by NKVD less than 100 years ago. We know nothing about these people: Who were they? Why were they killed?

Belarusian bones are unburied bones. Walking in those woods, one finds personal objects with inscriptions scratched upon them—words speaking to us, the living. Belarusian bones are speaking bones. Belarusian bones are also scattered bones—there was so much forced dislocation, from World War I to the Soviet Labor camps. A bone is indeed “a key to my motherland.” A bone is also an answer to the question, “Where am I from?”

“We think of memory as something in the past, but memory isn’t organized temporally. Memory organizes itself around poetic associations, images, around ‘how it feels.’ It brings the living and the dead together by making them share one breath. Poetry is medicine: It heals that invisible, ripped things inside us.”

6. One of the books by Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich is called the Unwomanly Face of War. The current resistance, on the other hand, has a very womanly face. Svietlana Tsikhanouskaya, a woman, is the real president according to the opposition. Women’s marches are held regularly on the streets of Belarusian cities and include Nina Baginskaya, a 73-year-old legend of Belarusian protest. In a traditionally masculine culture, how and when did women get to the forefront of the protest?

I read this title as a confrontation: You think that the face of the war is unwomanly, but in fact, the war has a woman’s face and a woman’s voice. Belarusian writer Ales Adamovich wrote his books about war because he couldn’t forget his mother’s face. A woman telling a story of her survival at the opening of a war memorial inspired him to write in his polyphonic style. Svetlana Alexievich is a student of Adamovich. When Alexievich started interviewing women veterans of World War II, what she heard from them was a new language—not the agreed-upon clichés. These women didn’t dare to repeat the official narrative of heroism, courage, and sacrifice because they thought it belonged only to men—male soldiers. To describe their experience, women had to invent their own language, and as a result, they were able to explain what it was like to experience the war as a human being.

If we look at the history of activism in Belarus, we will see that it has never been “a traditionally masculine culture.” The only thing that was traditional was describing it that way. Now that there is so much visibility, everybody sees the women who have always been there. While here in the States, “babushka” is a character for a comedy sketch, the babushka of our nation—Nina Baginskaya—has been standing in front of rows of armor-clad police, alone, year after year, for decades.

7. You once said, “Poetry is the language the dead use to help us forget that they are dead.” In your book, you remember the dead, you speak with the dead, and you resurrect the dead with words and melodies. For this, you go back to the past, but in the past, the history is “a closed-down shop.” Do you think that poetry can help open that shop?

No, but I think that it can help us cope with the fact that it’s closed. We think of memory as something in the past, but memory isn’t organized temporally. Memory organizes itself around poetic associations, images, around “how it feels.” It brings the living and the dead together by making them share one breath. Poetry is medicine: It heals that invisible, ripped things inside us. Derek Walcott wrote, “The classics can console but not enough.” I won’t speak for the English-language classics, but when it comes to Belarusian, Polish, and Russian poetry. . . I’m a reader because our poetry has been consoling me. It wakes up a feeling inside me, a kind of a feeling I would never dare to approach without poetry.

“I write in English to make the Belarusian experience visible in it. . . [and] I write in Belarusian because, to put it briefly, it’s the most badass language I know.”

8. Music for the Dead and Resurrected is written in English. You also write in Belarusian. Can you explain the difference between these two languages for a poet, and why it is important for you to write in both languages?

8. Music for the Dead and Resurrected is written in English. You also write in Belarusian. Can you explain the difference between these two languages for a poet, and why it is important for you to write in both languages?

Music for the Dead and Resurrected was written in two languages. I write in English and Belarusian at once, making changes back and forth, making it impossible for a single language to lay claim to originality. Neither of my poetry languages is my mother tongue, since—like most people in Belarus—I grew up speaking Russian, which was my stepmother’s tongue and a colonial heritage. I can translate from Russian, I can have sex in Russian, but I cannot write a poem in Russian.

I think of all three languages as one: a storage of linguistic material. I don’t believe in translation. I believe in moving through this storage room, listening carefully.

I write in English to make the Belarusian experience visible in it. Also, I write in English because the tradition that allows me to grow as a poet today is the reparative, postcolonial English-language poetics of M. NourbeSe Philip, Robin Coste Lewis, Saidiya Hartman, Claudia Rankine, Carolyn Forché, Don Mee Choi, Ilya Kaminsky, and Natalie Diaz. I’m equally inspired by multilingual writers like Uljana Wolf and Eugene Ostashevsky. These writers have created a space within English from where I too can speak. These are writers who confront English, and this is what I do too: I confront English about my absence in its global idea of itself.

I also draw on the polyphonic Belarusian anti-literary prose tradition of Ales Adamovich and Svetlana Alexievich and on the anti-literary poetics of Polish poets like Czesław Miłosz, Wislawa Szymborska, and Anna Swir.

I write in Belarusian because, to put it briefly, it’s the most badass language I know.

9. You dedicate this book to your daughter Korah. How old is she now? What do you want her to get from this book?

Korah is eight, and I want her to have my voice asking, “Where am I from?” as a kind of home.

10. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

Lots of things moved me from a young age: music, opera, books, apple trees, the geometry of our apartment, snow, my grandmother’s body, my parents’ love, stories of children—like me—being tortured during World War II and how they would never give up the location of partisans. Since a young age, I wondered whether I’d be able to tolerate torture.

I took buses and trolleybuses around Minsk, and the rhythm of bus stops—people getting on and off—played an important role in shaping me as a poet. The book that comes to my mind right now is Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Blue Bird.

Valzhyna Mort is the author of Factory of Tears and Collected Body. She has received the Lannan Literary Fellowship, the Bess Hokin Prize, the Amy Clampitt Residency, the Gulf Coast Prize in Translation, and the Glenna Luschei Prairie Schooner Award. Born in Minsk, Belarus, she writes in English and Belarusian.