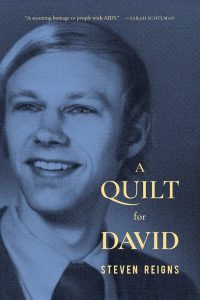

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America Los Angeles speaks with Steven Reigns, author of A Quilt for David (City Lights Publishers, 2021).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

At 16, my friend slipped me Anaïs Nin’s Delta of Venus. She said, “It’s the best smut you’ll ever read.” She was right! But what moved me more than those sexy stories was the preface. It was an excerpt from the diary of this—to me at the time—unpronounceably-named writer. She wrote about the importance of nuance and poetry.

I wanted to know more about her and soon picked up her published diaries. I found Nin’s writings at an ideal time in my life, as she wrote about relationships, living as a writer, and pushing through insecurities.

2. How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

My momentum with A Quilt for David wasn’t hard to maintain. Research has a scavenger hunt feel to it that’s exciting. Personal interviews were incredibly interesting as I talked to people who were directly involved. What kept me inspired to research and write was the question that got me started in the first place: What really happened in that dental office?

“I love writers and see us as having a great impact on culture. Journalists educate on what is really happening, novelists and poets give us an emotional experience to relate to and reflect on, historians tell us about the past and allow us to see warnings and patterns, academic writing helps us examine the messaging we are given.”

3. How can writers affect resistance movements?

I love writers and see us as having a great impact on culture. Journalists educate on what is really happening, novelists and poets give us an emotional experience to relate to and reflect on, historians tell us about the past and allow us to see warnings and patterns, academic writing helps us examine the messaging we are given.

4. What is your favorite bookstore or library?

City Lights Bookstore has always held a special place in my heart, and I go often during my frequent trips to San Francisco. As bookstores’ poetry shelves shrink, City Lights still has an entire floor devoted to my beloved form. Their devotion to arts, world literature, and progressive politics is impressive. The massive public support of their fundraiser during the pandemic attests to the vital place City Lights fulfills. It’s a historic literary institution.

I want to also note the importance of the used and remaindered books sold at libraries. The funds from these sales usually benefit nonprofits that help support library programming. I don’t use an electronic reader and love picking up these books to read while traveling or at the beach or in the bath.

“Writing is how I found my voice. The page is where I felt safest to express my lived experiences and how I felt. Those early writings were confrontational and confessional, which required me to push through fear. . . . I tell my students that feeling fear while writing is a sign you’re doing it well. A big part of poetry is saying the unsaid.”

5. Your book unearths an important story of bias and false accusation during the early years of the global AIDS epidemic. Here we are in the midst of a very different epidemic. Has this project impacted your experience of this moment?

I’ve been deep in this project for 10 years and have seen how fear feeds hysteria and misinformation. It’s important to think critically about reports of “super spreaders.”

At the start of the Black Lives Matter protests, there were articles and social media posts positioned to blame new COVID cases on the protesters. They were fueled by bias and not scientific data. America has a long history of creating scapegoats that conveniently coincide with who they hate. Catherine O’Leary, when anti-Irish sentiment was at its height, was blamed for the Great Chicago fire of 1871. A local journalist later admitted to fabricating his reporting on her cow kicking over a lantern. With David Acer, homophobia automatically made it easier for the public to believe an avowed virgin over a gay man in 1991.

6. What surprised you during your process of writing and research?

6. What surprised you during your process of writing and research?

When researching, I put an ad in the local Stuart, FL paper with my phone number looking to talk with patients, friends, and colleagues of Dr. David Acer. I was shocked by how many people called to give me their opinion, despite having no personal knowledge of him. Some didn’t even live in the area at that time. That level of hubris was a surprise to me.

I think we’re in a moment where people feel emboldened without actually doing the work or research or any study of craft. This is seen in the arts. Writer Justin Sayre once quipped, “Instagram doesn’t make you Avedon.” We’re seeing this unfold now with non-scientists dispensing anti-vaccine information.

7. What is the role of fear in your writing life? Of love?

Writing is how I found my voice. The page is where I felt safest to express my lived experiences and how I felt. Those early writings were confrontational and confessional, which required me to push through fear. That sense of daringness was thrilling, and I soon extended it to publishing. I tell my students that feeling fear while writing is a sign you’re doing it well. A big part of poetry is saying the unsaid.

“I identify as a gay man. The experience of growing up as an outsider positioned me to be an observer. I think everything I do is informed by my gay sensibility.”

8. How does your identity shape your writing?

I identify as a gay man. The experience of growing up as an outsider positioned me to be an observer. I think everything I do is informed by my gay sensibility.

9. What advice do you have for young writers?

There is value in writing, even if it’s never published. Everyone on a dance floor is there for the love of dance. Not everyone will be a professional dancer. The same is true of writing. There is a reward and joy to the writing itself. Publication or prizes isn’t necessarily where one finds happiness or worth.

10. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

For the past 16 years, I’ve taught a free autobiographical poetry writing workshop to LGBTQ seniors. We’re in a youth worshiping culture that doesn’t encourage disclosure or creativity. For my LGBTQ elder students, moving beyond those restrictions and writing about their lives is a bold task. Their writings excite me in each and every class. I think in those workshops, they’re creating some of the most important writings today.

Steven Reigns is a Los Angeles poet and educator and was appointed the first poet laureate of West Hollywood. Alongside over a dozen chapbooks, he has published the collections Inheritance and Your Dead Body is My Welcome Mat. Reigns holds a BA in creative writing from the University of South Florida, a master’s in clinical psychology from Antioch University, and is a 14-time recipient of the Los Angeles County Department of Cultural Affairs’ Artist-in-Residence Program’s grants. He edited My Life is Poetry, showcasing his students’ work from the first-ever autobiographical poetry workshop for LGBT seniors. Reigns has lectured and taught writing workshops around the country to LGBT youth and people living with HIV. He is currently touring The Gay Rub, an exhibition of rubbings from LGBT landmarks, and facilitates the monthly Lambda Lit Book Club. His newest collection, A Quilt for David, is out now from City Lights Publishers, the product of 10 years of research regarding dentist David Acer’s life.