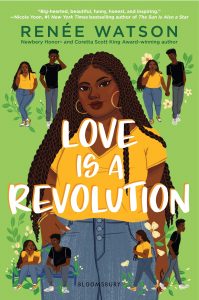

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Renée Watson, author of Love is a Revolution (Bloomsbury YA, 2021).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I was introduced to poetry as a young girl, and I think it really shaped the way I saw myself. You can’t read Nikki Giovanni, Maya Angelou, Lucille Clifton, and Eloise Greenfield and not feel powerful, beautiful, and worthy. Their poetry was such a gift to me as a little Black girl growing up in Portland, OR. I needed their affirmations.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I believe fiction can be a way of processing reality. All of my fiction is anchored in something I’ve witnessed, something I’ve experienced, or even something more distant, like a statistic or a news article I’ve read. That’s one way I think about grounding my work in truth, but writing from a true place for me is more about creating stories that resonate with my readers so that even if they’ve never been in that particular circumstance, they know that feeling.

“All of my fiction is anchored in something I’ve witnessed, something I’ve experienced, or even something more distant. . . but writing from a true place for me is more about creating stories that resonate with my readers so that even if they’ve never been in that particular circumstance, they know that feeling.”

When I think about writing realistic fiction for teens, specifically Black girls, I see my writing as a way of saying, “I see you. Yes, what you’re experiencing in real life is really happening—here is a way to cope, here are characters going through what you are going through, and here is how they are dealing with it.” Writing realistic fiction for young readers also allows me to write the world that is and also as it could be.

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I start most of my writing by making lists in my journal. I spend a lot of time getting to know my character and her world before I actually start writing the story. I interrogate her, asking what her fears are, who loves her, who doesn’t, who makes her smile, who makes her want to hide, what does she want, and what’s in the way of getting what she wants. Once I have a sense of these answers, I start writing.

I always start off handwriting and then eventually, I type it out. When I’m feeling stuck, I go back to my journal and handwrite. That usually helps me get unstuck. There is something about pen to paper that makes me more vulnerable. And that vulnerability, in turn, helps me get back to the heart of the story and reconnect to my inspiration.

When it comes to maintaining inspiration, I often turn to photography and music to take in a different way of storytelling—to fill the well, so to speak. I have to say sometimes—a lot of times—I don’t feel inspired to write. But I have to. Writing is hard, and there are always reasons not to write, always distractions. So instead of waiting for the inspiration to strike, I’ve worked on being disciplined. I set a schedule for myself and block out time to write. Sometimes, those writing sessions are magical, and I am in the zone and it’s all coming together. But sometimes, the words come slow, and I doubt myself or get lost in my own plot. All of it is a part of the process, and I am committed to the process.

4. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I just finished The Selected Works of Audre Lorde, edited by Roxane Gay. Up next is One of the Good Ones by Maika and Maritza Moulite.

“I spend a lot of time getting to know my character and her world before I actually start writing the story. I interrogate her, asking what her fears are, who loves her, who doesn’t, who makes her smile, who makes her want to hide, what does she want, and what’s in the way of getting what she wants. Once I have a sense of these answers, I start writing.”

5. In Love is a Revolution, the protagonist Nala, a plus-size teen, struggles with issues of self-confidence and often compares herself to others, but her beauty and love of her body are never questioned—to her or others. Moreover, the popular girls—against whom she compares herself—are driven and intelligent, rather than shallow, unlike the popular girls we might be used to seeing in young people’s literature. In your writing process, how did you decide which YA conventions to adhere to and which to forgo?

Deciding to push back against some of the troupes of teen rom-coms was very intentional. I wanted a dark-skinned Black girl with a big body to be the desired one, not the side character. It was important for me to have body diversity in the book. In Love Is a Revolution, the characters—like people in real life—come in a variety of sizes. Still, weight is not the focus of the story. Nala has things to work on, but it’s inward work. I wanted to show what it can look like to have big, Black girls at peace with their skin tones and size in a world that often shames and degrades girls who look like them. It felt radical to let these girls exist without apologizing for their bodies.

I also wanted to show the nuances of relationships girls have with each other. The “mean” girls are self-righteous in their convictions. Because of their age, they are overzealous when it comes to their activism. That choice provides less room to paint the characters as bad or good, right or wrong. All of the characters in the story have moments when they shine and moments when they can do better. Life is messy, and love is complicated. I wanted to get at that.

6. Along with being a writer, you’ve been an educator for the last two decades, teaching theater and creative writing. How does teaching inform your writing, either in practice or content?

Teaching makes me a better writer. Having to break down the craft of writing for my students has absolutely made me think about the choices I make in my own work. Some things come naturally to me, and so it’s helpful to unpack how I do what I do. The more I teach, the more I learn about myself.

In a very practical way, teaching young people gives me a close-up view of their lives. I learn so much about how teens are navigating home life, school life, community activism—so many of my stories are inspired by the young people in my life.

7. Love is a Revolution is a love story covering—and often challenging—concepts of romantic love, familial love, and self-love. What do you think is the greatest misconception surrounding love that we’re most often taught as teens through film, literature, and other media geared toward young people?

7. Love is a Revolution is a love story covering—and often challenging—concepts of romantic love, familial love, and self-love. What do you think is the greatest misconception surrounding love that we’re most often taught as teens through film, literature, and other media geared toward young people?

We teach young people that love is easy. That it is a fluffy word—heart emojis and flowers. But love is hard work. To truly love a person or a community requires perseverance, grace, patience, and forgiveness. It is being able to deeply care and critique at the same time. And so, if that is what it takes to love others, the work to love oneself is tremendous. Self-love is not only about making time for pampering or quoting affirmations. Loving yourself is hard work. Self-love means not giving up on yourself, and offering yourself grace, patience, and forgiveness. To care for and critique yourself. I don’t think we say this enough, especially not to young people.

8. Have you ever written something you wish you could take back? What is the most daring thing you’ve put into words?

I haven’t wished I could take something back, but I have wished I had written more. After publishing This Side of Home, I realized I had more to say. The story follows identical twin sisters who are adjusting to their gentrifying neighborhood. The sisters deal with microaggressions, interracial dating, and racial tension at their school. I realized after writing it, that I really wanted to explore those themes even more—specifically how it all plays out in Portland, OR.

I wrote Piecing Me Together as a companion novel to This Side of Home. Instead of interracial dating being the focus in the novel, Piecing Me Together goes into interracial friendship, with an emphasis on class. Craft-wise, it felt daring because I experimented with chapter lengths (chapter one is only two sentences; some chapters are lists). I also decided not to give the main character a romantic love interest, which felt like breaking an unspoken YA rule. To date, writing Jade’s story is the most vulnerable writing I’ve done. There were scenes that I wrote and after writing them, I’d think, “Am I really going to let her say that? Admit that?”

“Find your people. Writing is very isolating, and you will need one or two people to lean on, share work with. You will need them to cheer you on when you want to give up.”

9. What advice do you have for young writers?

I often tell young writers to be excellent when no one is looking. Now is the time to focus on craft, to experiment and find your voice while there is no contract, no big readership. I think it’s important to enter the industry having a sense of self and a clear vision of what kind of work you want to create.

My other advice is to find your people. Writing is very isolating, and you will need one or two people to lean on, share work with. You will need them to cheer you on when you want to give up.

10. Why do you think people need stories?

We need stories because we all need to be seen, validated. I have a few of my favorite quotes hanging up in my writing space. One that reminds me of why storytelling is important is a quote by James Baldwin: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

Renée Watson is a New York Times bestselling author, educator, and community activist. Her young adult novel, Piecing Me Together (Bloomsbury, 2017) received a Coretta Scott King Book Award and John Newbery Medal. Her children’s picture books and novels for teens have received several awards and international recognition. She has given readings and lectures at many renown places including the United Nations, the Library of Congress, and the U.S. Embassy in Japan and New Zealand. Her poetry and fiction centers around the experiences of Black girls and women, and explores themes of home, identity, and the intersections of race, class, and gender.

Her books include young adult novels, Love is a Revolution, Piecing Me Together, This Side of Home, and Watch Us Rise (co-written with Ellen Hagan). Her middle-grade novels include the Ryan Hart series (Ways to Make Sunshine and Ways to Grow Love), Some Places More Than Others, Betty Before X (co-authored with Ilyasah Shabazz), and What Momma Left Me. Her picture book, Harlem’s Little Blackbird: The Story of Florence Mills, received several honors including an NAACP Image Award nomination in children’s literature.

One of Watson’s passions is using the arts to help youth cope with trauma and discuss social issues. Her picture book, A Place Where Hurricanes Happen, is based on poetry workshops she facilitated with children in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Watson was a writer-in-residence for over 20 years teaching creative writing and theater in public schools and community centers throughout the nation. She founded I, Too Arts Collective, a nonprofit that was housed in the home of Langston Hughes from 2016 to 2019. Watson is on the Writers Council for the National Writing Project and is a member of the Academy of American Poets’ Education Advisory Council. She is also a writer-in-residence at the Solstice Low-Residency Creative Writing Program of Pine Manor College.

Watson grew up in Portland, OR, and splits her time between Portland and New York City.