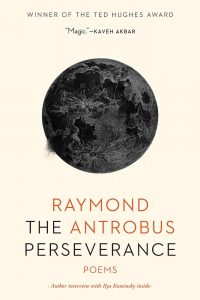

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Raymond Antrobus, author of The Perseverance (Tin House, 2021).

1. How can writers affect resistance movements?

Honestly, I’m not sure they can—at least not on their own. I agree with the Toni Morrison quote about our culture needing fewer famous individuals and more famous movements. I think the most practical change I’ve witnessed has been in the classroom: getting students reading and thinking outside of their usual curriculum. Also, getting people to write about who they are in the world and articulating what they may be up against.

I did some work for English PEN in London a few years back. All my students were in the United Kingdom as refugees and asylum seekers. I met up with them once a week for three months to engage in poetry lessons. At the end, many of those students had written poems about their lives and were invited to the UK Parliament to showcase their writing. These stories were put in front of policymakers who were moved by the stories they heard that day.

At the most, those young writers stopped a bomb being dropped; at the least, they were given a platform and were heard and seen—not just by the political powers in that room but by their peers and family, who got to learn something new about them. These opportunities can make real change by nurturing confidence and talent and building creative and conscious communities anywhere, from classrooms to prisons to parliaments.

2. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

George Orwell’s travel writing had a direct and immediate effect on me as a young reader. Down and Out in Paris and London and Burmese Days blew my teenage mind. As soon as I had opportunities to travel, I started journaling on the trips inspired by those books. That same year, I noticed a book of poems called Jamaica: An Epic Poem by Andrew Salkey. This book-length poem sat on both my parents’ shelves (they lived separately), and I dipped into it over the years. I understood very little of it, but there were parts I found deeply moving—just in the energy of its language and the way it weaved in and out of time, place, and dialect.

“When my poetry became public, I felt it had to serve other functions if I expected to have readers. I had to align myself with schools of thought, with history and language. Writing poetry became about joining a conversation, a lineage of other voices.”

3. How does your writing navigate truth? Do you think poetry, as a genre, has a distinct capacity to engage with hidden truths?

I’m not sure. That’s a lot of pressure to put on poetry. Something can be false and emotionally true, and we all know why that’s dangerous given the times we’re living through.

4. The poems in The Perseverance draw on a number of your life experiences as a Jamaican British person who is deaf. Has processing your own life through writing allowed you to glean any new perspectives on your past? Do you find autobiographical writing to be a therapeutic practice, or more of a duty that can be heavy and frustrating?

Hmm. . . I think writing poetry at first was a therapeutic practice, as was my journaling and “travel writing,” but that was all private. When my poetry became public, I felt it had to serve other functions if I expected to have readers. I had to align myself with schools of thought, with history and language. Writing poetry became about joining a conversation, a lineage of other voices.

5. What’s something about your writing habits that has changed over time?

I was mentoring a young poet earlier today, and they were talking about how they only write poetry when they’re sad. There was a time when I would’ve strongly identified with this, but that’s not the case nowadays. Writing only when I was sad was probably less me practicing a craft than it was managing my emotions. My early poems all probably had the same tone—introspective, angry, heroic—and my writing now engages with literature as well as my own life. That’s a significant change.

“Writing only when I was sad was probably less me practicing a craft than it was managing my emotions. My early poems all probably had the same tone—introspective, angry, heroic—and my writing now engages with literature as well as my own life. That’s a significant change.”

6. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

This is a very broad question, and I don’t like giving individual names because I always leave out someone important. . . But honestly, the genre is in a good place because of how much poetry brilliance is in the world right now—everywhere. Earlier this year, I was one of the virtual tutors for the Obsidian Foundation, a retreat for Black poets from the diaspora. I was invited by Nick Makoha (a brilliant British Ugandan poet). There were poets from across Europe, the Caribbean, and North America as participants. The talent was off the charts, and I’m incredibly excited about the work that will be forthcoming from that community.

7. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I have been rereading the collected poems of Juan Ramón Jiménez and Emily Dickinson recently. I had been mostly reading contemporary poets lately and felt a need to read something outside of that for escapist reasons. Some poetry collections that have been inspiring me are A Woman Without a Country by Eavan Boland, Other Exiles by Kamau Brathwaite, and Supplying Salt and Light by Lorna Goodison. Next, I plan to read Your Crib, My Qibla by Saddiq Dzukogi.

8. Your poem “Sound Machine” discusses the power and burden of language, among many other things. You examine the weight behind your father’s middle name “Osbert,” a name derived from Old English that he kept hidden his entire life because he believed it was given with the intention to “bleach him, / darkest of his five brothers.” In the literary world, language is so often celebrated as a tool of empowerment, but we seldom discuss its capacity to oppress and perpetuate violence against historically marginalized people—a point that is so centered in your work. What steps should today’s writers take to ensure that they’re not contributing to injustices that can be compounded by abuses and misuses of language?

8. Your poem “Sound Machine” discusses the power and burden of language, among many other things. You examine the weight behind your father’s middle name “Osbert,” a name derived from Old English that he kept hidden his entire life because he believed it was given with the intention to “bleach him, / darkest of his five brothers.” In the literary world, language is so often celebrated as a tool of empowerment, but we seldom discuss its capacity to oppress and perpetuate violence against historically marginalized people—a point that is so centered in your work. What steps should today’s writers take to ensure that they’re not contributing to injustices that can be compounded by abuses and misuses of language?

You could probably have a whole literary career examining that one question. I don’t know, I guess because the people I grew up around and the people I learned the most from aren’t writers themselves—they have no stake in the literary world—so I see this could be more of a question about who gets to tell their stories, who gets prized, who gets sidelined?

I don’t think my work is that revelatory; I think it is pretty specific. I grew up in Hackney in the ’90s when it was one of the poorest areas of London, I was raised by an English socialist-minded mother and a Black Jamaican Rastafarian, and I was part of many different worlds—even at school, between the hearing part of my education and the D/deaf part. If I’m finding language for my fullest and most honest self, then most of that is showing up in the work, which in turn means my work is examining the language that has both empowered and harmed people I love and people I identify with. That answers how I came to write a poem like “Sound Machine.”

“If I’m finding language for my fullest and most honest self, then most of that is showing up in the work, which in turn means my work is examining the language that has both empowered and harmed people I love and people I identify with.”

9. The narrator in many of your poems experiences mishearing, resulting in lines that are the product of omissions and adaptations from the original speaker. As a genre that allows for flexibility in traditional sentence structures and sounds, poetry seems uniquely equipped to describe the subversion of normative language structures and the complicated relationship that D/deaf people have to language. Can you imagine The Perseverance existing as a work of nonfiction or any other literary form?

Yes, I love this question. I went through a phase of reading James Joyce, and he has mishearings and misunderstandings all over the place in his prose. He does little to “correct” himself—sometimes he delves further into his confusion, and the prose sometimes ends up demonstrating the discovery of itself. So in short, yes, I could’ve written this book in other forms, but my most natural mode is poetry. I will always be a poet first.

Having said that, there are other versions of this book: There’s an audio version of The Perseverance, there’s the published collection, and then there’s the live version that I perform with a BSL interpreter and friend of mine, Anna Kitson. The poems are different in all of these forms.

10. Aside from being a writer, you’re a founding member of Chill Pill and Keats House Poets Forum, two event series and literary communities for poets. What do you think is the greatest takeaway from having a community of fellow writers to engage with? How has this community changed for you during the pandemic?

Yes, I organized poetry showcases and workshops for a decade in London. That time was nurturing two things: a writing community and an audience for poetry. In a way, they were the kind of practice that Toni Morrison spoke about—movements over individuals. Chill Pill and Keats House Poets Forum are both poetry collectives that served different purposes. Keats House Poets was funded by the Keats House Museum, aimed at getting young writers to engage with the poetry and life of John Keats.

Keats is largely misunderstood as a figure. He was a working-class, Cockney-speaking young man. He was loathed by the literary critics of his time because of his so-called “lowly English.” Now, Keats is acclaimed and paraded by all the elite institutions, and his working-class roots are often erased.

Chill Pill is a bit more grassroots in that it was just friends of mine getting together and putting on poetry showcases in theaters, bars, and festivals around the United Kingdom. That time taught me a lot, and I have friendships that have lasted to this day, out of that. During the pandemic, I’ve been more engaged with friendships and just checking in with people that I hadn’t spoken to in years. It’s not easy keeping connections with people, and that work is important too.

Raymond Antrobus FRSL was born in London to an English mother and Jamaican father. He was awarded the 2017 Geoffrey Dearmer Prize, judged by Ocean Vuong, as well as the 2019 Sunday Times/University of Warwick Young Writer of the Year Award. His second full-length collection of poems, All the Names Given, is forthcoming from Tin House and Picador in 2021. Antrobus currently lives in Oklahoma City.