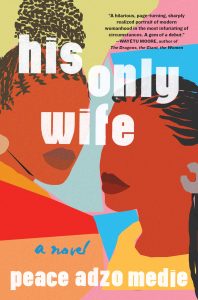

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Peace Adzo Medie, author of His Only Wife (Algonquin Books, 2020).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I’ve been impacted by many books, but one that has profoundly impacted me as a writer is Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. After reading it as a teenager, I began to think seriously about how I could use words to create images and to effectively show the reader what I was thinking. Before then, my focus had been on producing fiction to entertain myself.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I’m very interested in presenting the truth of people who are not centered in mainstream narratives. But I’m also fascinated by how we construct our version of truth, by how two people can have the same experience and not only describe it differently but also believe that their version is the only truth. The novel I’m currently working on excavates this phenomenon.

“In the social sciences, we know. . . that our identities matter for our research: They matter for what we research, how we conduct our research, and how we write our findings. In the same way, I think our identities matter for the stories we tell and how we tell them.”

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

Before I begin writing a book, I spend months—and sometimes years—thinking about characters and plot. In fact, I like to think that a lot of my writing happens in my head and I spend a great deal of time with characters and their stories in my thoughts, before I write anything down. But because I also work on multiple research projects, on which I also publish—so far, a book and several academic journal articles—I tend to switch back and forth between thinking about fiction and nonfiction. Therefore, there are long periods when I don’t focus on fiction.

However, when I’m able to think and write about fiction, I very much enjoy it. I began writing fiction for myself when I was about 10 years old, because I ran out of books to read. I discovered that I enjoyed it almost as much as I enjoyed reading. Therefore, I think the pleasure I get out of writing fiction is what enables me to maintain my momentum and interest—and is the reason I’ve been writing for almost 30 years, even though most of what I’ve written has not been read by anyone.

4. How can writers affect resistance movements?

An important role that writers can play is in documenting resistance movements. This can ensure visibility, facilitate recognition, and bring marginalized voices to the center.

5. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I recently read Ocean Voung’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, and now I’ve just begun Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other.

“Stories serve so many purposes. We need them because they document our truths, they magnify our dreams, they teach, they entertain, they inspire. Stories allow us to peek into the lives of others, and they also allow us to see ourselves.”

6. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

My identify plays a huge role in my writing. I’m Black, Ghanaian, and a woman, and one of the reasons I wrote His Only Wife was that I was hungry for stories of Black women just living their lives and doing regular things. In the social sciences, we know—although some continue to resist this truth—that our identities matter for our research: They matter for what we research, how we conduct our research, and how we write our findings. In the same way, I think our identities matter for the stories we tell and how we tell them.

7. Why do you think people need stories?

Stories serve so many purposes. We need them because they document our truths, they magnify our dreams, they teach, they entertain, they inspire. Stories allow us to peek into the lives of others, and they also allow us to see ourselves.

8. Establishing authority is arguably the first and most important task of the writer. The first sentence in your debut novel, His Only Wife, states: “Elikem married me in absentia; he did not come to our wedding.” It’s confident, creates a sense of urgency, and answers the question: “Why should I keep reading?” Is this how you always envisioned beginning the novel? What tone did you want to set for the rest of novel with this sentence?

8. Establishing authority is arguably the first and most important task of the writer. The first sentence in your debut novel, His Only Wife, states: “Elikem married me in absentia; he did not come to our wedding.” It’s confident, creates a sense of urgency, and answers the question: “Why should I keep reading?” Is this how you always envisioned beginning the novel? What tone did you want to set for the rest of novel with this sentence?

I had a variation of this opening line early on in the writing process, even before I completed the first chapter. Although characters and plots change when I begin writing—mostly because the characters tend to grab the story and run away with it—I always knew that Afi’s marriage to Elikem would be unconventional and even turbulent. I, therefore, wanted to set this tone early on in the book, to hint to the reader that this relationship was going to be a bit unusual and that there were going to be bumps along the way.

“Respect is important and something that is very much needed in society, but has been constructed by some to mean submission and self-denial, especially in regard to young women. It has therefore been used to box women in, to limit them, and to shut them up. Furthermore, young women are constantly being told to respect men, but society rarely puts the same pressure on men to respect young women. So, partly to oppose this, I decided to write about ‘disrespectful’ women.”

9. The novel features three women—Afi, the narrator, Evelyn, and Muna—whose relationships with each other I won’t reveal to readers, but I mention because despite three different life tracks and opinions about each other, the characters are connected through their fierce independence as women. Whether a character has always been this way or took time to grow into it, their stance is a rooted resistance against cultural norms. Can you discuss the importance of giving space to voices like theirs—women who speak freely about their wants and desires—which range from human decency and respect, to sex and financial prosperity?

Women who resist cultural norms in a variety of ways are everywhere, and in writing them, I’m simply reflecting reality, which is an important thing to do. I especially wanted to write about such women because in Ghana, and in most places in the world, they face a lot of backlash. I, therefore, wanted to normalize the act of resisting, of defying. In fact, in Ghana, women who push back against cultural norms are often described as “disrespectful.” Respect is important and something that is very much needed in society, but has been constructed by some to mean submission and self-denial, especially in regard to young women. It has therefore been used to box women in, to limit them, and to shut them up.

Furthermore, young women are constantly being told to respect men, but society rarely puts the same pressure on men to respect young women. So, partly to oppose this, I decided to write about “disrespectful” women. I think such narratives are important because hopefully, they will help to normalize women who resist ideas and practices that are harmful to them or put them at a disadvantage.

10. Following Global Norms and Location Action: The Campaigns to End Violence Against Women in Africa, which was published in March, His Only Wife is your second published book this year. In what ways does your scholarly work inform your fiction, if at all? Does fiction influence your scholarly writing? How does each form feed your intellectual and creative curiosity?

My fiction, including His Only Wife, is very much influenced by my scholarly research and writing. Much of my scholarly work focuses on gender, politics, and armed conflict. A big part of this is understanding the ways in which gender norms shape women’s lives, beginning with the home and extending to women in political office. My book, Global Norms and Local Action: The Campaign to End Violence against Women in Africa, is about how post-conflict states respond to violence against women.

For the research project on which the book is based, I conducted interviews with a range of people, including survivors of intimate partner violence in Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire. I was struck by how pressure from relatives and friends contributed to some women staying in relationships with violent partners. This got me thinking about the reasons that women enter and stay in romantic relationships and influenced my writing of His Only Wife. While there is no physical violence in Afi and Elikem’s relationship, it is very much a story about a woman facing some pressure to get married and then trying to make that marriage work.

One way in which fiction has influenced my scholarly writing is by helping me to better communicate my ideas. I began writing fiction many years before I began writing research articles and books, and I think that long process of learning how to write about fictional characters and their lives has strengthened my writing skills in ways that have been beneficial for my scholarly work. Both forms of writing enable me to explore the themes that interest me.

Peace Adzo Medie is a Ghanaian writer and senior lecturer in Gender and International Politics at the University of Bristol in England. Prior to that, she was a research fellow at the University of Ghana. She has published several short stories, and her book, Global Norms and Local Action: The Campaigns to End Violence Against Women in Africa, will be published by Oxford University Press in 2020. She is an award-winning scholar and has been awarded several fellowships. She holds a Ph.D. in public and international affairs from the University of Pittsburgh and a BA in geography from the University of Ghana. She was born in Liberia.