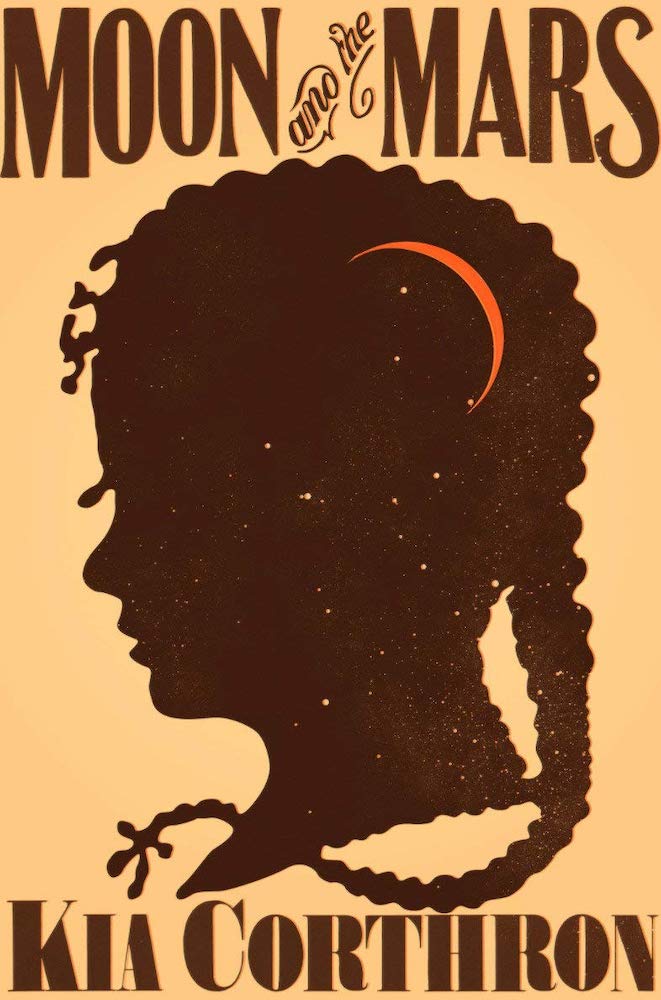

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America Los Angeles speaks with Kia Corthron, author of Moon and the Mars (Seven Stories Press, 2021).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I grew up in a working-class town in the valley of the Maryland Appalachians, a 10-minute walk from West Virginia. My mother was also born and raised there, and most of her formal education was pre-Brown v. Board of Education at the county segregated Black public school. The area was a good 95 percent white.

When my sister Kim and I were small, one of my mother’s former teachers from the African American elementary—an elderly Black woman—gave us big boxloads of ancient kids’ chapter books, which thrilled us. One of the novels I picked was Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter. I’d never heard of it. I was delighted by the title character’s glad game! How she brought joy to all the local townspeople (who were all white)! And then, in the 32nd and final chapter, the penultimate page of the book, a Black character appears. Pollyanna has been seriously injured, but suddenly there seems to be a real possibility of healing, and everyone is so happy, “Even Black Tilly who washes the floor, looked through the piazza window and called me ‘Honey, child’ when she wasn’t crying too much to call me anything.”

Kids, I hope, are more sophisticated now, but this was the ’70s in the sticks. A complete shot to my 10-year-old gut: the first time I felt betrayed by a book. Porter wrote a sequel, and several other female authors took the reins for a total of 14 in the series, but I never read another. Though, in writing this, I just discovered that the very next writer after Porter—who penned the third through sixth books—was Harriet Lummis Smith, who in 1890 became the first African American public school teacher in Boston, a racially integrated system. (For the record, in the portraits I can find of Smith, she looks fair enough to pass, but I don’t know if those images have been doctored.) So perhaps all these decades later, for academic reasons, I may go back to the glad game after all.

“When weaving nonfiction elements into an invented narrative, unless it’s a time travel book and the point of the story is to rewrite history, I believe it’s a matter of ethics to be historically accurate in portraying real characters. That doesn’t mean a living or dead icon can’t interact with fictional characters. . . . But unless the characterization is so outlandish that it is obviously untrue, I find it problematic—unjust—to just make up stuff about a real person even if they are long dead.”

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I have strong opinions about this, but they will be peppered by all the “unless” exceptions to my rule. When weaving nonfiction elements into an invented narrative, unless it’s a time travel book and the point of the story is to rewrite history, I believe it’s a matter of ethics to be historically accurate in portraying real characters. That doesn’t mean a living or dead icon can’t interact with fictional characters. There’s no deception in that; the reader is aware that this is a novel, that the author created the conversation. But unless the characterization is so outlandish that it is obviously untrue, I find it problematic—unjust—to just make up stuff about a real person even if they are long dead, particularly negative stuff, for the sake of entertainment or alleged literary value.

In my first novel, The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter, famed African American union organizer A. Philip Randolph comes to dinner in the home of my fictional characters, an event that clearly never took place outside of the book. But my characterization of Randolph is truthful, at least insofar as are the biographies I’d read of him. If an author penned a story wherein Harriet Tubman could sprout wings and fly, carrying slaves to freedom, I’d have no problem with the premise because it’s so obviously and deliberately absurdist. On the other hand, if an author were to take a real historical figure and, with no shred of evidence, present him as, say, a pedophile—that, I would find dodgy, to say the least. (I didn’t provide an example in the last instance because I wouldn’t want to suggest a lie that might inadvertently plant itself in the minds of anyone reading these words.)

3. What is your favorite bookstore or library?

The flagship New York Public Library—the “lions” library! I love sitting and writing in the reading rooms: the enormous main one on the top floor, but also smaller ones tucked in the lower levels.

I have several favorite indie bookstores, but I want to give a particular shoutout to Word Up Community Bookshop in Washington Heights—an easy stroll from my Harlem apartment—run by a collective of 60-plus neighborhood volunteers. My editor Veronica Liu was the founder and is currently the general coordinator.

4. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I had just finished Richard Powers’s The Overstory—most of which I found breathtaking, making me see trees differently and new—before heading to Vermont for a week visiting friends. I brought another book with me—well-written but drove me crazy because it played with confusing fiction and memoir in a way that left me feeling manipulated, so I put it down and replaced it with a loan from my friends’ shelves: The Best American Short Stories 1990. As far as I got, it was excellent. Now that I’m back in New York, I just started Brit Bennett’s The Mothers.

“For artists working in fiction, we have more protection as our work is addressing what has been exposed rather than participating in the exposure itself. We also have the option to present thinly veiled fact as fiction. The greater peril is self-censorship, which often starts with self-denial.”

5. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

In the United States, I believe it’s the accelerated and abusive application of the Espionage Act, starting with the Obama administration, to target journalists and whistleblowers. The purported reasoning is to protect U.S. military, but as evidence indicates, in reality it’s about punishing those who expose American government transgressions or military atrocities.

Among the most famous cases (all under Obama) are Chelsea Manning, imprisoned for seven years for her military leak to WikiLeaks (founder Julian Assange has also been charged), which included video of U.S. helicopter troops in Baghdad firing on journalists and other civilians; Edward Snowden, now in asylum in Russia, a civilian contractor who released data revealing the National Security Agency’s program of widespread surveillance of Americans; and Reality Winner, who served five years in prison after releasing NSA in-house documents reporting on Russian attempts to interfere with the 2016 U.S. presidential election. It appears that the government is betting on a chill factor to silence others who dare consider laying bare American wrongdoing.

For artists working in fiction, we have more protection as our work is addressing what has been exposed rather than participating in the exposure itself. We also have the option to present thinly veiled fact as fiction. The greater peril is self-censorship, which often starts with self-denial. Regarding the previous paragraph, for example, there are many who gave President Obama a pass, or just turned a blind eye, to improprieties that would have outraged them had the same transgressions been committed by his predecessor or his successor.

6. Moon and the Mars features characters both fictional and historical, and boasts an impressive bibliography. How does research drive or inform your storytelling?

History very much informed my narrative in Moon and the Mars. I’d settled on the years 1857 through 1863 for the body of the book because I wanted Seneca Village to be a part of the story—it no longer existed after 1857—and I wanted to include the draft riots of 1863. Each year would represent a section, with several chapters in each section. My process can be outlined through the following steps: 1) Peruse annual national and local headlines, 2) decide which of those events would be significant in the lives of my protagonist Theo—a half-Black, half-Irish girl growing from childhood to adolescence—and her family and friends, 3) make decisions about how to divvy up this information into chapters, 4) focus on the notes I just prepared for the next chronological chapter, and 5) write that chapter.

I provided certain literary quirks to clarify the historical moment: newsboys calling headlines, newspaper clippings (which I could insert word-for-word as work published before 1926 is in the public domain), postings, and letters.

I was very focused on details: Was that idiom invented yet? Exactly how long would it take a letter to get from there to here? Sometimes I could find the answer, and sometimes—after laborious effort—I couldn’t. That’s when I would have to piece together something that would make sense based on the facts I had. Very rarely I would fudge a bit, such as the Barnum’s American Museum performers working in the summer of 1860—they weren’t necessarily all there at that time—but I clarify my poetic license in the book’s afterword.

7. What is the most surprising thing you discovered in the process of writing Moon and the Mars?

7. What is the most surprising thing you discovered in the process of writing Moon and the Mars?

Everything! Well—a lot about New York and the country, from 1857 to 1863. For instance, there were numerous cigar factories in Manhattan and Brooklyn with plenty of female laborers, and Black men tended to be paid significantly more than white men because of skills handed down and shared over generations from former Southern tobacco slaves.

In 1859, just 13 months before the start of the Civil War—and thus, so “late in the day” that many people hoped slavery was grinding to a halt—a two-day auction of more than 400 people from the same plantation constituted what is considered the largest single sale of enslaved Americans in history. In the Five Points slum district of lower Manhattan, there was much social intermingling of Irish and African Americans, such as in the dance halls. A merging of African stomp traditions and Irish stepping eventually came to be known as “tap dance.”

8. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

During the pandemic, I read quite a few excellent novels—three of which I unequivocally loved, finding them, as I say of all my favorite reads, “good to the last drop”: Deb Olin Unferth’s brilliant, quirky, animal-radical Barn 8; Sarah Waters’s meticulous and exquisite page-turning The Paying Guests; and Douglas Stuart’s delicate, intimate, and harrowing debut Shuggie Bain. Unferth and Waters were new to me, so I plan on catching up, and I am eagerly awaiting Stuart’s sophomore.

Meanwhile, I have my old standbys: Viet Thanh Nguyen (especially The Sympathizer and The Refugees), Jesmyn Ward (especially Salvage the Bones and Men We Reaped), and for nonfiction, Robin Kelley (mostly anything, but certainly Freedom Dreams, Hammer and Hoe, and Thelonious Monk).

“History very much informed my narrative in Moon and the Mars. I was very focused on details: Was that idiom invented yet? Exactly how long would it take a letter to get from there to here? Sometimes I could find the answer, and sometimes—after laborious effort—I couldn’t. That’s when I would have to piece together something that would make sense based on the facts I had.”

9. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

People who loved this book are going to dismiss me as a literary dolt resistant to experimentation, but Michael Ondaatje’s Divisadero drove me nuts! For the record, I’m a big Ondaatje fan, starting with the early, spare stuff: The Collected Works of Billy the Kid and the stunning Coming Through Slaughter. The memoir Running in the Family is also truly elegant.

But Divisadero! The first half: I was riveted. It felt like my thrill-ride virgin voyage with Jane Eyre—nothing wrong with a good old-fashioned page-turner! As I read, integrating my established fandom with my current exhilaration, I consciously anticipated: Divisadero is going to be one of my all-time favorite novels! And then, with the rising action rushing to a heart-thumping climax. . . everything stops. The story completely changes, going all intellectual on me with some quiet, internal, unrelated meditation that continues for the remainder of the book!

I’m polite, so if I ever met Mr. Ondaatje, I’m sure I would just tell him how much I love his work—which, for the most part, is true. But in my fantasyland, the conversation would go: “Michael, if I may call you that: Please go back to the first half of Divisadero and finish it!”

10. Your work is known for its dialogue and use of dialect, as well as nonverbal languages such as Black American Sign Language. What draws you to languages?

I was a playwright decades before I began writing novels, so instinctually, I create characters fundamentally through their speech.

There are four protagonists in The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter, one of whom is a white deaf man who becomes involved with a Black deaf woman. He discovers, through her, that there is Black sign language, which like Black English, is not a different language but a variation on the same tongue. In the novel, I also make verbal distinctions in the hearing characters between childhood and adulthood and between working and educated classes. And there is the protagonist with shining potential—the eighth grade valedictorian—who suffers unforeseen life setbacks and regresses in his elocution.

Early on, I’d fiddled with a chapter or two of what would become Moon and the Mars, not having yet decided if I would follow through with this idea for a novel. There was a lot of history to grasp, so I set aside those initial creative forays and dove full-scale into research. Among the dialogue challenges I had laid out for myself: Irish immigrants of the mid-19th century (most intimidating!); an escaped Black slave (as an African American writer, I felt more at home here—still, I wanted at all costs to avoid cliché); a biracial girl brought up in both communities; that same child growing from seven years to 13, her parlance maturing with both age and education.

Months went by, and while continuing to absorb fascinating 18th-century happenings, it occurred to me that it was high time I started applying those facts to my story. I knew full well that I needed to write my characters’ voices in order to hear them and hone them, and still I persisted in my procrastination, checking out yet another historically relevant library book. Then one morning, instead of opening a search engine, I reached for my notebook and began to take those cautious first committed steps into the novel, which starts with Theo’s words: “Mutt I am.” I wrote Theo’s family and Theo’s friends, and as I’d anticipated, their vernacular was, at first, amiss. But I knew their voices were only patiently waiting to be revealed, and with every draft, I moved exponentially closer.

Kia Corthron’s debut novel, The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter, was the winner of the 2016 Center for Fiction First Novel Prize and a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. She was the 2017 Bread Loaf Shane Stevens Fellow in the Novel. She is also a nationally and internationally produced playwright. For her body of work for the stage, she has garnered the Windham Campbell Prize for Drama, The Horton Foote Prize, the United States Artists Jane Addams Fellowship, the Flora Roberts Award, and others. She was born and raised in Cumberland, MD, and lives in Harlem, New York City. Moon and the Mars is her second novel.