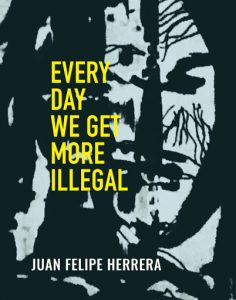

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jenn Dees speaks with Juan Felipe Herrera, author of Every Day We Get More Illegal (City Lights Publishers, 2020).

1. Why do you write?

1. Why do you write?

Poetry is where I live. It is where I discover and jot down insights that come to me and demand a home. As you know, poems have a habit of disappearing in a flash. What’s odd is that writing is more than writing—it provides something that moves and encourages personal, cultural, and universal forces to seek a new orientation, as the great Chinese essayist Lu Chi would suggest. It also bends time. With the poem, I can design a little corner for my families that have passed to live on, and for those brutalized by society to continue and be honored—to generate kindness.

2. How can writers affect resistance movements?

Writers are part of everything, as is everyone else. However, we choose to pause and take note, rethink, meditate, and most of all, to respond with wiggly words. This is one of the most important things social beings can practice—to participate in, provide, and exhibit new ideas in new ways, in compact social space, a page, or an audience. “Impact” takes time. For the poet, “impact” is most present in a “reading.” A “reading” creates a collective “communitas”—that is, an almost-ecstatic binding sense of community, as anthropologist Barbara Myerhoff wrote in the ’70s when describing the early stages of social movements.

“Writing is more than writing—it provides something that moves and encourages personal, cultural, and universal forces to seek a new orientation, as the great Chinese essayist Lu Chi would suggest. It also bends time. With the poem, I can design a little corner for my families that have passed to live on, and for those brutalized by society to continue and be honored—to generate kindness.”

3. What is the relationship between poetry and protest?

They are the same. And they are different. The poem can become the charter, the proclamation, the manifesto. It can contain key phrases, icons, master symbols, and condensed stories of the history before, during, and after the protests—all of this is possible with a poem and the poet. The key is for the poem to call for nonviolence and unity. A poet is always protesting—with her previous conceptions of self, family, nature, forced identity, history, the social constructions of cultural value systems and language itself, time itself—she seeks an entire radical new galaxy.

4. What is your favorite bookstore or library?

All multicultural bookstores, women’s bookstores, LGBTQ+ bookstores, and used-book bookstores, since I was in middle school in San Diego. Bookworks in SF during the ’80s. Prairie Lights in Iowa City and the one and only City Lights in San Francisco’s North Beach (since I was a teen Beatnik)—my favorites.

The Library of Congress, during my time as U.S. Poet Laureate, became my second home—and it’s a vast resource for all. In the Hispanic Division, I was treated to Lorcas’s chapbooks, Cervantes’s early editions of Don Quixote (including the pirated version), early photos of Jorge Luis Borges, recordings from the ’50s of Angel María Garibay Kintana (translator and historian of Nahuatl poetry; my uncle Roberto Quintana had the same voice and style). Not to mention recent recordings of Miguel Leon-Portilla, another key Nahuatl thought and culture historian and pace-setter of the Chicano/Latinx cultural “Renaissance” of the late ’60s. The Prints and Photographs Division was a vast and incredible resource of images, silk screens, a painting by Rembrandt, and it even included the presidential campaign poster of “Abram” Lincoln (the entire name, “Abraham,” was too long for the design!). I thank all the librarians of these divisions. Did I tell you that the Laureate space is nestled in the Poetry and Literature Center? And I didn’t get to the American Folk Life Center, the Rare Books Division and. . . well, I just love libraries.

“The poem can become the charter, the proclamation, the manifesto. It can contain key phrases, icons, master symbols, and condensed stories of the history before, during, and after the protests—all of this is possible with a poem and the poet. The key is for the poem to call for nonviolence and unity. A poet is always protesting—with her previous conceptions of self, family, nature, forced identity, history, the social constructions of cultural value systems and language itself, time itself—she seeks an entire radical new galaxy.”

5. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today?

The highest tiers of power often can be against free thinking and inclusive expressive culture. We need to further open the doors for multicultural, multilingual, and LGBTQ+ voices. A significant project could be the translation of early cultural texts of as many ethnic groups as possible in the United States. For example, the poetry of Nezahualcoyotl (1402–1472), the Mexica prince of Texcoco—near what is now called Mexico City. Poems for the Mexica contained insights and ethical values regarding our role on earth, offerings to life—given the impermanent meters of our existence. We need to ask ourselves, “What are my sources? Where are they? How do I and friends translate them?”

6. How does your identity shape your writing?

The historical experience of Latinx people, Native, and people of color fuels what we want to say—what you and I want to say. It is true for all groups. However, the question of power is always at play. Power gnaws at us, from every corner of our day-to-day life. Division, hate, anger, war, racism, denial, and life suppression based on misperceptions, disinformation, mytho-violence, and screwy media cuts through our lives. Identity is a call to freedom. Writing is that call.

7. What advice do you have for young writers?

Think of writing as you. Writing is not outside of you. Most important are your ways of speaking; your language(s); your home-talk, stories, songs, and chants; your group’s style and speech flavors. Start with your way. Then, include others’ ways. The library is your experimental station. Tour and taste as many materials as possible. Select your favorite book sections—visual art, philosophy, original, rare texts (Darwin’s notebooks, for example). Notice the world, the people in this world, quandaries, questions, images, lives, voyages, maps, sketches, lifestyles of the 11th century, the Chinese Star Charts of the 1200s. Kickstart your super-self! And write with its many fun, deep, flying powers. Embrace humanity—with five words.

A poet is a wanderer, a mountain climber with invisible peaks and imaginary trails. Carry a raggedy notebook, tablet, sketchpad, colored pencils, old-school fountain pens. Be the new techno-word-monster of the world! Your mantra: “I have a beautiful voice, and you have a beautiful voice.”

“Language contains live links to our ancestors, to their source teachings, to the now and the pre-future. Without language, we lose ourselves and drift away to a partial and frozen sense of identity and an archipelago of abandonment and invisibility.”

8. Your collection references writers from all over the world, including Elias Canetti, Bashō, and Nelson Mandela. What do these writers mean to you?

8. Your collection references writers from all over the world, including Elias Canetti, Bashō, and Nelson Mandela. What do these writers mean to you?

They are all bold, brave, perceptive, and extremely open to a much bigger world than themselves. They were walkers through society, nature, and culture. They gained deep knowledge; observed quietly (some loudly); noticed the tiny things, the incredible things; found their purpose—writing, meditating on their outscape and inscape, reflecting on suffering and oneness. They were concerned with unlocking the ways of society, power, nature, and the world. And they did.

9. Why do people need stories?

To continue their story as members of a social and cultural orb. To respond to the overarching stories of who we are, to generate dialogue—the key to peace and vibrant world humanity.

10. You work in both Spanish and English, and also reference languages that have been lost. What do you believe languages contain, and what do we lose when they are no longer spoken?

Language contains live links to our ancestors, to their source teachings, to the now and the pre-future. Without language, we lose ourselves and drift away to a partial and frozen sense of identity and an archipelago of abandonment and invisibility.

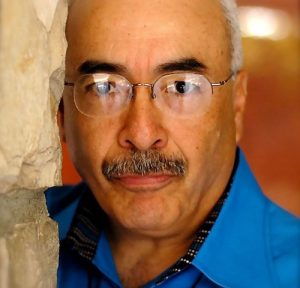

Juan Felipe Herrera was the 21st U.S. Poet Laureate from 2015 to 2017, the first Latino to receive this honor. The son of migrant farm workers, he was educated at UCLA and Stanford University, and received his MFA from the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His numerous poetry collections include Notes on the Assemblage (2015), 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border: Undocuments 1971-2007 (2007), Half of the World in Light: New and Selected Poems (2008), and Border-Crosser with a Lamborghini Dream (1999). Notes on the Assemblage was named a best book of the year by The New Yorker, The Washington Post, Library Journal, NPR, and BuzzFeed. In addition to publishing more than a dozen collections of poetry, Herrera has written short stories, young adult novels, and children’s literature.