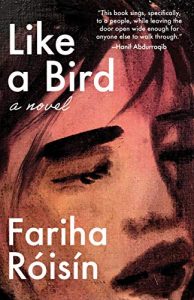

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Katie Zanecchia speaks with Fariha Róisín, author of Like a Bird (The Unnamed Press, 2020).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

Wow. This is a big question. I’m thinking very surface level about the books that impacted me as a kid: I used to love The Clan of the Cave Bear, The Lord of the Rings (I changed my name to Arwen when I was 11 and demanded everyone called me that), and The Chronicles of Narnia series—but I think the first time I was really struck by anything was when I read White Teeth at 11. I met Zadie Smith a couple of years ago and told her that to read about the existence of a Bangladeshi—in popular culture, as a young person who had no other representation—was so necessary for me. I clung to it. I think it made me realize I could exist; I could have a story. I started writing Like a Bird a year later.

2. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

I recently read Sultana’s Dream by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, a Muslim Bangladeshi, who wrote this feminist utopia in 1905. I was so floored by her prescience, by her futurity. It also pained me to think of how we quash women of their brilliance. Rokeya wasn’t allowed to go to school; to be a writer, I assume, was an abstract privilege in that sense. I think about erasure a lot and talk about this with my friend Tanaïs often. I’m a Muslim, Bangladeshi queer woman—all of those identities are constantly being dimmed and silenced. The South Asian diaspora mainly represents high-caste Indians and Hindus. So, I don’t feel represented by them at all. As a country, Bangladesh is currently underwater, and with climate change will it even survive in 40, 50 years? Futurism, as Octavia Butler showed us, is necessary for our survival. When you’re a people who are not remembered, to find artifacts and mirrors is a psychic reckoning. Finding this book was a reminder that a torch has been lit, and we have a duty to continue to bear it, for the freedom of all those who are voiceless. To remember us, to remember who we are. To know that there is an archive.

“If people read Like a Bird and believe in the possibility to heal, especially and primarily survivors of all abuse—if they can walk away and understand that they are their own compass, their own map, the keepers of their own story, their own truths—then I feel like we can get closer to toppling patriarchy. Because my own abuse has made me a warrior. It’s made me learn how to fight.”

3. So much of Like a Bird takes the reader wandering through New York City. What is your favorite bookstore, library, or place to wander?

I love this concept of flâneur/flânerie, and in so many ways that was how I got to understand and know New York—by walking through the cobbled streets, past the pristine ivy and the cement against the Hudson River, the East River. The first time I moved to NY, I was 19—and back in those days, I would walk around the still-grungy LES or ungentrified Williamsburg. So much of my life in NY was informed by the music I was listening to on my headphones—the likes of The Velvet Underground, Radiohead, Beach House, Nina Simone. Or the books by Susan Sontag and Toni Morrison I’d read in Cafe Reggio. Then, I got really fond of walking through Brooklyn. A couple of months ago, I walked with my friend from Dumbo to Crown Heights, right to the edge of Brownsville, and it was sublime. My favorite places in NY are the nooks: I love the secrets of the city, the mystery, when it feels like it’s talking directly to you, when it lets you in on its magic.

4. One of the early questions in the novel centers on the definition of freedom and the existence of boundaries. What does freedom mean to you generally, and also in the context of creativity and craft? What boundaries do you hope this novel tears down or builds up?

Because Like a Bird is a book about surviving a rape, societally I hope to initiate more conversations—to eventually topple patriarchal notions—about the responsibility that we have to each other. Men need to start considering how they have bought into patriarchy, and how they benefit from it. Writing—especially writing that is considered and revolutionary—is about the future. How do we want to evolve? For me, the best kind of writing both contends with this, and leaves us with hope to continue toward something bigger. James Baldwin was profoundly good at this, of pointing out our failures, and asking more from us. As was June Jordan, Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, Sylvia Wynter.

The lineage of Black American writers is so potent and powerful because they wrote out of convention, but spoke to the ailments that are pervasive and noxious with us. The fact that I can read Ruth Wilson Gilmore and believe in abolition, of its possibility and necessity, is why writing is so important. If people read Like a Bird and believe in the possibility to heal, especially and primarily survivors of all abuse—if they can walk away and understand that they are their own compass, their own map, the keepers of their own story, their own truths—then I feel like we can get closer to toppling patriarchy. Because my own abuse has made me a warrior. It’s made me learn how to fight.

5. Your writing often focuses on colonization, and the contemporary manifestations of systemic racism and a deep-rooted history of occupation—of culture, of identity, of body—and Like a Bird is no exception. How do you hope this novel contributes to anti-colonial work?

My mind reverberates to the beat of anti-colonial thought and perspective. I’m so lucky to have been raised by a father that made me hyperaware of colonization, and though I—like (maybe) a lot of nonwhite kids that grew up in mainly white spaces—acquiesced to whiteness, I was also always quite suspicious of it as well. In Australia, I was aware of participating in settler violence/colonialism—and Like a Bird, I should mention, was written first in Sydney, and was initially set there—and had an understanding that I live on stolen land, and I wanted that to be palpable in Taylia’s conception and mind. For me, I can’t live without that understanding. It is my entire compass. I hope this book allows people to think more deeply about the lives of nonwhite folks.

My friend Aria Aber, who blurbed the book and was one of the first people to read the final version, pointed out that there’s no real main white character except Taylia’s mother. I didn’t write to or for whiteness, and I certainly didn’t write to fit into it either. That was a risk I had to take to be true to myself as a thinker, but also the story. I wrote a character, like myself, that is very suspicious of the structures of power and hopes for a future beyond it.

“That’s the power of truth: When you listen to yourself, it can guide you to a universe where you can win, whatever that looks like. I haven’t won a lot in my life, so there’s no reason for me to have ever believed I’d get this far. . . For me, the relationship between truth, history, and dreams is that I listened to the truth—my truth, the truth of this story—despite the trauma of my personal history to navigate and participate in my own dream-making.”

6. The power of history, memory, and our dreams—how they manifest physically and spiritually—feature prominently in this novel. In fact, you write of Taylia: “My dreams became a portal to my own survival.” How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth, history, and dreams?

6. The power of history, memory, and our dreams—how they manifest physically and spiritually—feature prominently in this novel. In fact, you write of Taylia: “My dreams became a portal to my own survival.” How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth, history, and dreams?

Well, my own dreams are a portal to my own survival. I dreamt the story of Like a Bird when I was 12, and I started writing it immediately. I still remember the morning after very clearly. So basically, it’s been a part of my life since I was a child, for more than half of my life. I wasn’t a particularly loved or cared for kid, and I definitely wasn’t supported. The most support I ever got was when my father got a colleague who was an English professor at the University of Technology Sydney to read the book when I was 16. . . just as I was about to graduate high school. I’m pretty sure it was because he thought I was full of shit and wanted me to stop focusing on writing and become a lawyer. I don’t know why I continued on the journey of finishing this book—what kind of audacity kept me going? Maybe just that I believed in myself—in the dream—I guess.

That’s the power of truth: When you listen to yourself, it can guide you to a universe where you can win, whatever that looks like. I haven’t won a lot in my life, so there’s no reason for me to have ever believed I’d get this far. I still don’t really see it as much of an achievement. I’m a Capricorn; I’ll probably die thinking I could’ve tried harder. For me, the relationship between truth, history, and dreams is that I listened to the truth—my truth, the truth of this story—despite the trauma of my personal history to navigate and participate in my own dream-making. I think I’ve always known I’m not lucky. So, I had to be a hard worker to make my dreams come alive instead.

7. You dedicate the book to survivors. What is the relationship between truth, memory, and survival?

In the realm of survival, “truth” and memory are complicated. We live in a society that is obsessed with a woman’s testimonial but still largely denies her any reprieve by humiliating her with disbelief, and she doesn’t get support from the justice system and society, either. The “truth” behind her words—without regarding how trauma creates a murky vision—is wildly misogynistic and profits only abusers. Many of us don’t remember because we don’t want to, not because we can’t. Then, when you can’t, you also feel like you’ve failed yourself, so it’s an endless loop that predicates history and memory as being a token of truth. Michaela Coel created one of the most incredible stories by making It May Destroy You (I mean, what a title) because it was made for survivors, by a survivor. She captured the hubris, the pain, the psychosis, the memory loss, and then the keen splices of remembrance that initiate survival. It’s such a phenomenal, integral piece of work. I hope Like a Bird can contribute to that kind of canon, one where survivors are both their own storytellers and the keepers of their truths.

8. Your art and storytelling traverse several different mediums, from a novel like this to poetry and podcasting. How can writers affect resistance movements?

I think of Aracelis Girmay who writes, “& so to tenderness I add my action.” There’s such a kindness to resistance because you’re asking for more, for a better society—you’re not settling for mediocrity. The best writing doesn’t settle, it pushes. For me, work that just shadows or mimics is uninteresting and also selfish. . . the market is saturated, so what do you have to offer? What a beautiful gift, to give society a resolution for revolution. To say: No. To say: Center your heart. To fight for Black liberation, for the end of capitalism, white inferiority, patriarchy, is to ask for humans to seek evolution. Writers have an immense responsibility to usher us into a better life.

“The thing is, I have nothing to lose. I’m a Bangladeshi Muslim queer—the game was never, ever made for me to win. So, I may as well say what I need to say.”

9. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

The biggest threat to free speech is white inferiority, capitalism, and patriarchy. When older writers and thinkers complain about “cancel culture,” what they’re really exposing is their own fragility. The irony is the pretense of “free speech” or “free expression” today. If J.K. Rowling is going to be transphobic, does she not understand that the natural cause-and-effect of that is that people will call her a TERF? Because that’s free expression, and it’s also a fact. People in power love posturing and demanding that they speak, even when they have literally nothing of value to say or share, other than hateful platitudes. It’s so boring to me. The establishment relies on the status quo because it benefits from it.

I remember growing up and reading Marty Peretz literally say Islamophobic and anti-Arab things, and then getting rewarded by being a Harvard professor or a consultant to Al Gore in the Middle East. It made me think that I’d never be allowed to be a writer because the writing world clearly didn’t want someone like me in it when the (former) publisher of The New Republic was saying such things. I’m pro-Palestinian and those are my politics, and there’s been plenty of times that I’ve been told by an older artist friend that I shouldn’t be open about my politics. The thing is, I have nothing to lose. I’m a Bangladeshi Muslim queer—the game was never, ever made for me to win. So, I may as well say what I need to say.

10. You write in Like a Bird, “I longed for family, I always had. But I don’t know if I ever really believed that I’d get it from my parents.” How do community and family support your work and writing process?

I don’t talk to my mother anymore, so there’s that. It’s not easy. Last year—the year my first book, How to Cure A Ghost, came out—was the first year I stopped talking to her. It felt painful because I suffer from a void, a darkness that subsumes me at times. I’ve had to unlearn the need for validation, which I suffer from because I was never satiated, I was never told I was good enough. I was never told I was good at all. At anything. Any writer can understand the isolation of writing, and to again feel the isolation of not being able to share this with my mother, will forever hurt me. But I have no choice. That’s my truth, and I must respect that.

My father supports my work, and he now tells me he’s proud of me. My sister too, though she’s often told me not to write about her. . . my girlfriend has said the same as well. I have good friends though—really incredible ones—that hold me, especially when I can’t see myself. That’s what I need more than anything. When I forget who I am, I need someone who loves me and is invested in me to hold my hand and show me a mirror, to gesture with kindness and say, “Look. Look at yourself. Look at what you’ve achieved. Look at how far you’ve come.”

Fariha Róisín is an Australian-Canadian writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, Al Jazeera, The Guardian, VICE, Fusion, The Village Voice, and elsewhere. Her work often explores Muslim identity, race, pop culture, and film. It also examines the intersection of being a queer Bangladeshi navigating a white world. She is the author of the poetry collection How to Cure A Ghost and the guided journal Being in Your Body. Like a Bird is her first novel.