The PEN Ten: An Interview with Victor LaValle

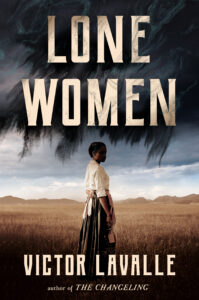

In Lone Women, a master of magical suspense, Victor LaValle, immerses readers in the 20th century American Western frontier. Inspired by a book about real women homesteaders, LaValle has crafted a propulsive, genre-bending novel. Featuring a cast of pioneering women, the novel explores the weight of secrets, the power—good and bad—of inheritance, and what happens when you confront the past.

PEN America’s Program Director, Literary Programs and Emerging Voices, Jared Jackson, speaks with author Victor LaValle, his former graduate school professor, about the nuances of history, universality of shame, and the long arc of the writer’s life (Amazon, Bookshop).

1. You’re a busy man. What is your writing practice like? Did it change at all as you were working on Lone Women, and balancing everything else in your life—family, teaching, an Apple TV adaptation of your previous novel The Changeling, to name a few?

I used to be busy in bad ways. Now, thankfully, I’m busy in good ways. For me, the child of a very practical, hard-working mom, that means being productive. What were the bad ways I used to be busy? It might mean checking the Amazon ranking for my most recent novel, or scouring Goodreads to see if anyone was writing reviews. Not to mention watching movies when I should’ve been writing and so on. So I was always busy but it wasn’t worth very much. These days I have a lot of projects bubbling and I feel pretty damn tired at times, but the difference is that I’ve created something by the end of it. A comic, a novel, a script for a television show. Those things might not even ever be released (TV being particularly fickle) but when I’m done I’ve still created something. Which has been so much better for my mental well-being than spending any time seeing what others think of the things I’ve created. So that’s the heart of my writing practice: make more work. It wasn’t the family or teaching that were taking up my time, in fact both are truly nourishing. It was that other stuff. And I’ve cut it all down by about 60%!

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

This answer has changed over time. When I wrote my first novel, The Ecstatic, I felt pretty brazen about the truth. By that I mean that I wrote about my family, some of it unflattering, and felt no qualms about airing that dirty laundry, that truth. It hurt my mother a lot. It would’ve hurt my sister too but, to her credit, she’s never read a page of my fiction. At the time I felt the right to share all this personal information because I was working through my own understanding of my family history. But I was writing without perspective, only a few years out from the events depicted in the novel. I didn’t understand, fully, how I felt about that time and I really didn’t understand the perspectives of the other people who went through it with me. Without that perspective I couldn’t possibly write the truth because I didn’t know it yet. These days I try to let a story sit with me a while before I share it with others, let alone publish it. Does that guarantee that I’m telling the truth? No. But maybe it gets me closer to it.

“The biggest trick for me is that I have good reasons for the secrets being kept, or withheld. What I want most is for the reader to think back and understand how or why someone would keep a secret. This requires my secrets being pretty good ones.”

3. What has felt like the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

See my answer above! I don’t wish I could take my first novel back. I’m incredibly proud of it. But I am glad I haven’t written another one quite like it again. It was a novice’s book, in all the best ways and some of the worst.

As for the most daring, I tried to write very honestly about marriage and child rearing in The Changeling. In particular, the distance that can set in between spouses when a child first enters the home. That felt like something daring to admit to. Some readers have let me know how much it meant to see that aspect of life in the book so I’m glad I did it.

4. During a conversation between two characters in Lone Women, Grace Price and Jerrine Reed, the latter says, “We applaud ambitious women.” The novel is made up of ambitious and varied lone women making their claim on unforgiving terrain. When did you know this would be your cast? How did the characters come to you, and how did you set out rendering them on the page?

Lone Women was inspired by a work of non-fiction, Montana Women Homesteaders: A Field of One’s Own, edited by Sarah Carter. That book is, as the title suggests, all about women homesteaders. So that defined my cast, but to find the particular people I read more. I learned about Bertie (Birdie) Brown, a real woman homesteader in Montana. She’s the only cast member based on a real historical figure. There wasn’t much known about her except for where she lived, how she made her living (selling moonshine) and how she died. For the others I fashioned composites from the many women I learned about in my research. And last I added just a drop of inspiration from real people that I know and love.

5. Notably, Lone Women leaves the familiar landscape of New York City featured in many of your books for 1915 Montana. What led you to exploring the early 20th century American West?

I published The Changeling in 2017 and felt I’d burned out my New York battery. I poured everything I love and hate about my hometown into that book, like Sauron did when he made the one Ring. The idea of starting a new book in the same place felt dull as hell. I was casting about for somewhere else. Maybe another country? Or another planet? But then I remembered that book about Montana women homesteaders. How about if I just wrote about another part of this country? A place that felt like the exact opposite of New York City, the plains of Montana.

“I didn’t change my identity in order to write the book, of course, but I had to be aware of my identity, my lens, and learn new ways of perceiving, of seeing, if I was going to do right by the women in the book.”

6. Lone Women opens with: “There are two kinds of people in this world: those who live with shame, and those who die from it.” What interests you about shame, and how did it become the catalyst for the novel?

I come by shame the old-fashioned way, I was raised with it. I’d guess that nearly everyone is. The reason for shame may change, but the idea of keeping secrets, about some familial or personal flaw that must be hidden, that seems damn near universal to me. There are very few feelings that you can guarantee nearly everyone has known. Hell, I’d bet more people are familiar with shame than with love, sadly. When you’ve got an experience that is likely to connect with so many, then you’ve got the chance to dive into a powerful current.

7. Secrets, good and bad, feature prominently in the novel. When characters use them for bad, many times its withholding information in order to manipulate other characters and bend them toward their will. As a modern master of suspense, on a craft level, how do you avoid withholding facts to solely manipulate the reader, and rather manage the flow of information that creates the tension and suspense of later reveals?

This takes many drafts! I loathe stories where information is withheld simply to extend the mystery. Like when two characters that should state their points of view clearly in a scene are given some contrived reasons for not doing so. There can be real reasons for this, of course: someone too afraid to confess their love for another; someone who hopes to avoid hurting another person’s feelings, etc. But the contrived reasons are grating when they happen. So the biggest trick for me is that I have good reasons for the secrets being kept, or withheld. What I want most is for the reader to think back and understand how or why someone would keep a secret. This requires my secrets being pretty good ones. And that’s where the drafts come in. Sometimes the secrets are terrible, the kind of thing no one would fret about sharing. I delete those.

8. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

My identity, or identities, is the filter through which I perceive reality. They’re like the lens on a camera, they help determine the kind of picture you take. For this book I had a chance to interrogate one of my primary filters, that of a heterosexual man. In my early drafts of my story, I had the wrong filter on when writing Adelaide and the other women. There were so many assumptions I made, so many blind spots, that only became clear as I shared my work, my plans with my wife and my agents, all of whom are women. I didn’t change my identity in order to write the book, of course, but I had to be aware of my identity, my lens, and learn new ways of perceiving, of seeing, if I was going to do right by the women in the book.

“What are the stories—the myths—that we begin to learn from our earliest days? And how is the relation of that history shaped by the people who share it? To think even more broadly we have to look at television and film, the lens through which so many people, in this country and around the world, understand American history.”

9. A refrain in Lone Women is: “History is simple. The past is complicated.” For many characters in the novel, this rings true. In what ways did you want to confront the distinction between history and the past? Does one allow us to “see” better than the other?

I wanted to dive into that distinction, history and the past. This, too, came about because of all the reading I was doing for the novel. So many nooks and crannies of the past were being revealed to me. They were, of course, written in history texts but they weren’t a part of what might be called popular history, generalized history. That’s the distinction I found interesting. What are the stories—the myths—that we begin to learn from our earliest days? And how is the relation of that history shaped by the people who share it? To think even more broadly we have to look at television and film, the lens through which so many people, in this country and around the world, understand American history. Where are all the non-white people? They’re gone. Or, if they do appear, it’s not how they would’ve seen themselves. They’re threats or servants and little else. I hoped my novel would complicate the picture of one place, during one time period, and maybe make people reconsider what they swear they know.

10. Your writing has changed over time, leaving behind the more literary realism of your earlier books to focusing on a blend that has been categorized as magical suspense. You’re also a creative writing professor. What advice do you have for emerging writers as they navigate the long game that is writer’s journey and their own creative interests?

One of the hardest things for me to imagine, as a newer writer, was the whole idea of a career, of longevity. When I published my first book, a collection of stories called slapboxing with jesus, I felt that the success, or lack thereof, would determine everything that happened for the rest of my writing life. The book was published. Yay! It enjoyed some good reviews and I traveled the country a bit doing book events. Great! But if I’m being honest, I also wanted that book to make me a million dollars and famed far and wide in the literary world. It did not manage those last two things. And at 27 I decided my writing career had tanked. What a waste. Oh well.

I look back on that poor, naive, egotistical version of myself and I want to give him a smack. I want to tell him that the arc of a writing life is long and rarely straight. The folks who hit big early may flame the fuck out, and the ones who keep at it, quietly and seriously, may find their careers grow in surprising ways but, more important than either of those possibilities is the drive to keep practicing the art that brings a sense of satisfaction. That’s the only part the writer controls.

Victor LaValle is the author of seven works of fiction: four novels, two novellas, and a collection of short stories. His novels have been included in best-of-the-year lists by The New York Times Book Review, Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, The Nation, and Publishers Weekly, among others. He has been the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, an American Book Award, the Shirley Jackson Award, and the Key to Southeast Queens. He lives in the Bronx with his wife and kids and teaches at Columbia University.