The PEN Ten: An Interview with Sunu Chandy

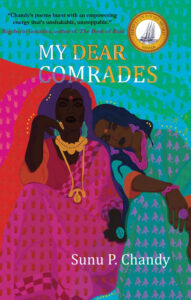

In her debut collection of poems, My Dear Comrades (Regal House Publishing), Sunu Chandy draws from her many disciplines–poetry, law, activism–to invite the reader into a space that resists boundaries while living among them. Her world is one of community and reflection, tender moments with loved ones, occasional brick walls, and a dedicated practice of surfacing suppressed voices, including her own. Chandy both celebrates her identity as a queer South Asian woman while also shining light on the attacks on LGBTQ+ and communities of color today.

In conversation with U.S. Free Expression Programs Manager Hannah Waltz for this week’s PEN Ten, Chandy discusses the poetics and politics of intersectionality, how her poetry and legal arguments interact, and the joy of others finding solidarity in her writing. (Politics & Prose, Bookshop)

Photo credit: Fid Thompson

1. This collection of poems, My Dear Comrades, beautifully resists summary as it spans great lengths of time and theme. When you started drafting the book, did you have a sense that it would be so expansive?

It’s hard to pin down any particular moment as to when this book began. I have been writing poems since high school, and over the years that was done more and more in community with other writers, including through an MFA program at Queens College, CUNY. During the pandemic, with necessary encouragement and the best kind of peer pressure from a terrific virtual writing community (Unicorn Authors Club), I gathered together some of my poems from before, during and after my MFA. With the coaching of Minal Hajratwala, who leads that group, I considered possible structures and groupings, and as importantly started to face my fears of whatever fallout might come from putting my poems out into the world. It was only then that I could seriously consider the possibility of publishing a full collection of poetry. Some of the poems reach back to early experiences living in New York City as a young civil rights lawyer, and some stretch into more recent times such as parenting a tween during the global pandemic or racial justice activism around removing Confederate statues from our town squares. One of the three sections of the book focuses on my journey to becoming a parent through both fertility struggles and the range of experiences involved with creating a family through adoption. While the timeframes and the themes are wide-ranging, the poems also frequently connect to broader social justice movements and a search for belonging and acceptance in a range of settings. Another arc in the book is from the first poem’s narrow guarded opening, where we must pretend in some ways to pass through to just watch someone seek individual economic gain as compared to the very last poem, a community poem.

2. You are a civil rights attorney, a social justice activist, and a poet. How do these disciplines and parts of your life interact with and inform each other?

First, as a writer in these spaces I aim to be both direct and nuanced. I appreciated that one of my favorite poets, Aracelis Girmay, used the word “lucid” to describe my work. I would imagine that this is an unusual adjective to use when describing either legal writing or poetry. In these spaces, either legalese or more flowery or abstract language may be what is expected on the page, or frankly, what’s seen as “interesting,” “valuable” or “sophisticated.” Amidst those dynamics, I seek to convey legal arguments and write poems with a clarity that can also hold interesting dynamics and difficult contradictions. In this time, we must be bold as we share what we experience as honestly as we can, and how that ties to what needs to change. At the same time, there is also a strategy and an art to conveying a message in a way that can be heard, perhaps with humor, or through first finding spaces of connection. I really enjoy figuring out how different communities use language and the real work of finding just the right word to convey a precise sentiment, and that goes for both legal briefs and poems. There’s a note at the end of the book about my WhatsApp messages with my cousin Saira in Kerala, India. We had a lovely discussion regarding how best to translate the word “comrade” into Malayalam. This exchange took me back to my MFA Craft of Literary Translation class with Professor Roger Sedarat. In that class we engaged in many negotiations regarding how words in varying languages may or may not carry the same tone or nuance, and considered what that means for our work to understand each other across identities and cultures.

“And there is always a question of shame in the background too, and what retaliation may come from sharing these stories. Through this book, I found a way to manage what I was going to share through these pieces, and when and how to best share that with others.“

3. You have been politically active since you were a teenager. How do you think writers can affect resistance movements? How can writers foster anti-racism, anti-sexism, anti-homophobia, etc. in their communities?

Absolutely, writers can play a crucial role in social change including highlighting examples of fighting injustice and humanizing the harms at stake which can help to change hearts and minds. In My Dear Comrades, I have several poems that touch on civil rights including a range of gender justice fights. For example, one of my poems is about a young South Asian woman who fights back through a legal case after facing sexual harassment at work. More recently, after the fall of Roe and the federal Constitutional right to an abortion, I felt moved to write a newer poem about my fertility journey and a related D & C. So many people are facing these situations today and medical providers in some states are afraid to care for people, even when patients are in life threatening situations. Anything we can do to humanize these harms in this moment is so crucial, in addition to bringing legal claims. Similarly, following the resurgence of #metoo, I have felt compelled to write additional poems about surviving sexual harassment. I have also risked including poetry in unusual legal settings like my farewell party when I left a civil rights leadership position in a large agency. I understood that to read a LGBTQ+ related poem and a poem that touched on language justice in a room with political appointees who were literally rolling back our rights in that moment was nothing short of a defiant protest. In that setting, I needed to be out as a queer person, and make clear that they could not also deny our humanity as they harmed us, if nothing else. I have also appreciated another lawyer telling me that my poem would move her law firm colleagues to better understand the need for racial and other kinds of diversity, far more than a bar graph or a chart. Finally, on the broader topic of art and resistance, I have to also give a shout-out to my super fantastic cover artist, Ragni Agarwal. Her brilliant representation of women of color and bodies of all sizes are also part of changing our culture to become more inclusive and joyful.

4. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today?

In our domestic context, the biggest threat to free expression is coming from a range of forces that are working aggressively to roll back baseline protections relating to our very bodies as women and queer people, and the broader work for racial and other inclusion that we have fought over decades to secure. So many of our communities feel under attack, and are under attack right now. In so many ways, our opponents have gone on the offensive. They’ve gone on the offensive to take LGBTQIA+ stories out of our schools, to take Black history and racial analysis out, to exclude transgender students from medical care or school sports, to shun LGBTQIA+ families by not allowing anyone to say gay. To quote the name of an important new coalition, we collectively need to be “Greater Than Hate” and come together to fight against these forces that harm all of us. Many of us fought so hard to have diversity training, and a greater understanding of racial and other diversity when hiring or creating our school environments. And now we are on the precipice of having baseline programs that allow some consideration of race in admissions, likely being chipped away at or ended by the radical and lawless majority on this Supreme Court. I have a poem towards the end of my collection called, “Tell us your reason for canceling,” that touches on these crucial questions. The title is based on an Expedia customer survey that I had to complete before getting my money back when I decided we would not enjoy staying in a Virginia hotel that until recently was named for a Confederate leader. Needless to say, that option wasn’t on the survey as a choice, but we know how to write things in.

5. How does your identity shape your writing? And what did you learn or discover about yourself in writing this book?

As a queer South Asian woman, many of my poems concern my identities directly, and for other poems it’s more in the background. My identities influence how I process the world and the encounters that I face which are then reflected in some of my poems. For example, as a woman of color, I do write directly about racism and sexism, and how I am perceived in the elevator of certain white neighborhoods, or in courtrooms. As a queer person I have a poem about being kicked out of a taxi cab, and others that touch on the lack of family acceptance. As the kid of South Asian immigrants, some of my poems are about growing up in a Christian Malayalee family. In these ways, my poetry is often bound up with my identities and how they operate together and in relation to other people. What I discovered about myself while writing this book was that I could take my questions and anxieties about sharing my work in stages and address them one by one in time, and that these worries didn’t need to stop me in my tracks as a writer. Specifically, as a parent I kept getting stopped at the question of whose stories are these, and whether I had the right to share my experiences of family building with the world. And there is always a question of shame in the background too, and what retaliation may come from sharing these stories. Through this book, I found a way to manage what I was going to share through these pieces, and when and how to best share that with others. I also discovered that many readers appreciate being reflected in these pieces, as women of color lawyers, as South Asian LGBTQIA+ folks and so on, because then they, and I, feel greater solidarity and less alone.

“I hope that this book helps to reflect that as LGBTQIA+ people, and as women, and as people of color, we must have a society where we can control our bodies, and who we love.”

6. The arc of queerness portrayed in these poems–coming out to your family, traveling with an early partner, going to dyke bars, marrying your wife, adopting your daughter–it’s as heartening as it is heart-wrenching. What do you hope your readers take from this representation of LGBTQIA+ life?

You named it accurately. Yes, it does feel heartening and heart-wrenching, both. I hope readers see the sorrow, the love, the care, and the fun that is part of this all, and connect to the humanity there. In our broader society, even in my lifetime I have lived through decades of reaching some seeming progress, for example, with LGBTQIA+ workplace civil rights protections confirmed through the Supreme Court’s Bostock case, and parallel to that I have enjoyed some increasing degrees of family acceptance. At the same time, so much discrimination and isolation remains. In our country this has now taken the form of not allowing LGBTQIA+ related books or content in some schools, even when these have been, and are, life lines for so many of us. Without seeing ourselves reflected in schools, I fear that we will have increased mental health challenges and a feeling like there is no space to hold us in this world even though we have existed for all of time in every culture and community. I have a newer poem that honors Urvashi Vaid, a fierce South Asian LGBTQIA+ and economic justice leader in this country who passed away in 2022. Many of us are carrying on the work in honor of her fighting spirit. And as an ally to the trans community, and a board member of the Transgender Law Center (TLC), I have to lift up that this is a time of immense outrage and activism given all of the bills that are passing in some states that don’t allow families to make their own gender affirming healthcare decisions. And of course this gender policing and control over our bodies is not solely for trans folks as such rules will harm anyone who dares to be their true selves and not precisely fit within some typical gender stereotypes. We also have to acknowledge that as with most areas, the safety that we have or don’t have as queer people is frequently tied to our race, economic privilege, and geographical location. While being out in a poetry book might feel risky to me for myriad reasons, I am also aware of my immense privilege in terms of my education, my age, my job, and because I am living in a progressive city like Washington, DC, where we have terrific local laws, but where we still need statehood. I also hope that being out as a South Asian person in this book can be helpful to those in our community who might feel alone. Ultimately, I hope that this book helps to reflect that as LGBTQIA+ people, and as women, and as people of color, we must have a society where we can control our bodies, and who we love.

7. I love that you invoke the names and works of so many wonderful writers throughout the book. If you could claim any writers from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be?

I was moved by the writings of many women of color writers during my college years and beyond. I will never forget when I came across the writings of Meena Alexander (Fault Lines) in a library when I was a college intern in DC as she was the first Malayali feminist author that I had come across. I also was so moved by the stories in The Alchemy of Race and Rights by Patricia Williams, who is now a law professor at Northeastern Law School. I will also never forget hearing June Jordan speak so much truth in Boston, and I want to name her clear spoken and stunning, “Poem about My Rights.” I adore the poetry of Naomi Shihab Nye. I particularly love Nye’s poems when she reflects the world we seek to build like the story she tells in “Gate A-4.” One of the first collections of poetry that I owned in college was “Circles on the Water” by Marge Piercy. I carried that book everywhere and appreciated her poems about nature and social justice and I will never forget the first poem that I opened the book to, “To Be Of Use.” There are so many incredible women poets, poets of colors, LGBTQIA+ poets and those of us at the intersections of these identities writing today. I am grateful for this current day community as much as I am for these literary ancestors. I am writing both in the tradition of the women of color writers in “This Bridge Called My Back” and the South Asian women who contributed to “Good Girls Marry Doctors,” edited by Piyali Bhattacharya. It’s hard to have the nerve to actually repeat this next part and so I kept stalling, but in her blurb on the back of my book, Arcelis Girmay included two names that floored me. She said my poems remind her of the work of Martín Espada and Audre Lorde. I read Zami by Audre Lorde in college in addition to her poems, and was truly blown away by her brilliance and truth telling. And I love the stories that Espada tells in his poems, and that we are both alumni of Northeastern Law School. I would say that I am writing in the company of all of these writers who have and continue to take risks and push past their fears in order to collectively create the lives of freedom and dignity that we all deserve.

8. You really know how to harness the power of extended metaphor; see: “Teaching My Daughter How To Re-Cap the Toddler Toothpaste” and “Grade Four Peaches.” Can you talk about your relationship to metaphor and how it became such a powerful instrument for you?

I would imagine that this is somewhat common among poets, but I am continually thinking in metaphors. I find that including metaphors in my poems comes naturally to me and often results in a more powerful and interesting story than referencing the thing directly. On my daughter’s recent middle school report card the teacher noted that she did best on recognizing poetic devices during this unit (lol). As you might guess, we practiced looking for these devices in poems at home, and she found some extended metaphors in my book. The first poem in my collection, “Just Act Normal,” is also an extended metaphor. This poem marks a relatively silly border crossing, but the process of embodying that waiting for the “guard” and trying to “get away” with something gives the reader a small taste of the anxiety folks must feel who are trying to get to safety and away from dictators, gender based violence, climate disasters, persecution for being LGBTQIA+, and/or economic hardships. How many contingencies refugees must come up with, and how many risks must they take in the process, given no other choices. This was a short opening poem that most directly raises immigration rights, yes, but also gestures to other contexts where some of us may try to “pass.” We may perhaps try to pass as straight, as not-disabled, as white, or in any way that hides who we are because we are afraid, and we know there are reasons to be afraid in some contexts. These are daily decisions for some, and I should also name that some that don’t even have that choice as highlighted in my piece, “Too Pretty.” This poem is both contained in my new book and published on-line in The Quarry by the poetry and social justice organization, Split This Rock.

“In my love note to my younger self, I would say, some things will get easier, and some may get harder, but just keep going. There will always be a community of activists, advocates, and artists who are inspiring each other and fighting for change, so find your people and your joy in the midst of it all.”

9. Your writing addresses that which is outside of our control, like natural disasters, death, sexuality, the pandemic, fertility. How does writing help you navigate these things?

I have written poems over the years to help me to grapple with hard questions or experiences. This is often how I try to make sense of things, or more often, come to some recognition, or perhaps even peace, that there is no making sense of it. This can include both how marginalized communities are treated in our society, and also the harms that we do to each other. These poems are sometimes a container for these immense experiences and a way to process the many nuances within them. During the pandemic it has been intense to be working at an organization that fights for the rights of caregivers and women in the workplace as we were also living through many of these challenging experiences. Similarly, in the poem “Symmetry” I describe listening to an affirmative action oral argument on-line in real time, while my daughter was taking her standardized tests virtually on the other side of the wall. The poem centers on the handout from the school saying we are not allowed to help our children. This handout became a symbol in my poem to challenge the ludicrous implication that all kids have equal access to tutoring, resources, educational settings that meet their needs or family support. This poem is sort of an updated counterpart to my original poem from long ago that centers on similar themes, “The candidate should hail from a well-regarded law school.”

10. In the spirit of the poem “To Satya, From Satya,” in which you find a Valentine your daughter addressed to herself, what would you say to your young self if you could write her a love note?

This question makes me smile. I would tell her that she’s got this, and that she will find her people. What comes to mind too is that I would likely warn her that it gets better and then, it does not get better, and so on. I would tell her that life goes on with these rolling hills, and that’s just the deal. Certainly, at this age I do feel far more freedom to be myself. I am grateful to have so many of my dreams realized in terms of becoming a parent, having a supportive partner, having a job that is the kind of work I wanted to do when I went to law school, and to have such a vibrant community of poets and other creative writers in my life. At the same time, last night at dinner my daughter asked if I saw the news regarding Uganda and LGBTQIA+ folks being imprisoned. And of course we don’t need to go that far away to feel unsafe as some of my trans friends are making plans about what they may need to do to leave this country. It’s a joyful, horrific, time in America, and I know many of us are fighting back with legal actions, with our creative writing, and so much more. In my love note to my younger self, I would say, some things will get easier, and some may get harder, but just keep going. There will always be a community of activists, advocates, and artists who are inspiring each other and fighting for change, so find your people and your joy in the midst of it all. A friend was telling me recently that she will have to use her school break for caregiving duties, and my one advice to her was to build in some fun too. There is no “someday” when all the work is done. I would tell my younger self, that as Oliver Burkeman writes, we have 4000 weeks in this life if we are lucky, and it serves us well to remember that as we go through our days. And this is actually not so different from the question that Mary Oliver posed to us long ago in her “The Summer Day” poem: ”Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?/ Tell me, what is it you plan to do / With your one wild and precious life?”

Sunu P. Chandy (she/her) lives in Washington, D.C. with her family, and is the daughter of immigrants to the U.S. from Kerala, India. Sunu’s work can be found in publications including Asian American Literary Review, Beltway Poetry Quarterly, Poets on Adoption, Split this Rock’s online social justice database, The Quarry, and in anthologies including The Penguin Book of Indian Poets, The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood and This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation. Sunu earned her B.A. in Peace and Global Studies/Women’s Studies from Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, her law degree from Northeastern University School of Law in Boston and her MFA in Creative Writing (Poetry) from Queens College/The City University of New York. Sunu started out as a union-side labor and employment lawyer and then worked as a litigator with EEOC for 15 years in NYC. Sunu is currently the legal director of the National Women’s Law Center and serves on the board of the Transgender Law Center. She was included as one the 2021 Queer Women of Washington and one of Go Magazine’s 100 Women We Love: Class Of 2019.