The PEN Ten: An Interview with Gina Chung

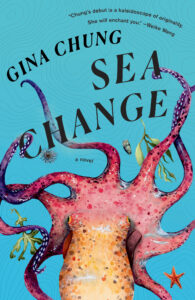

Gina Chung’s Sea Change is one of the most anticipated debuts of 2023. Its heroine, Ro, finds her own way into adulthood as she tries to make sense of her scientist father’s absence, her best friend’s upcoming wedding, and her ex-boyfriend’s new life—on Mars—all under the watchful eye of her closest companion, a giant Pacific octopus named Dolores. Sea Change is a funny, sweet, and deeply felt novel from an exciting new literary talent.

In conversation with Literary Awards Program Director Donica Bettanin, Gina — a former PEN America colleague — discusses the grounding power of nature in her work, a lifetime of reading, and this summer’s signature cocktail. (Amazon, Bookshop)

1. Sea Change introduces its protagonist, Ro, at a time when her closest companion is a giant Pacific octopus: the irresistible and inimitable Dolores. Can you share a bit about your own relationship with the natural world, and how it informs your writing?

I find the natural world to be very grounding. Living in New York City as I do now, I don’t get too many opportunities to spend extended amounts of time in nature, but even just being in the presence of trees or plants in a park or community garden calms me. As human beings, we tend to think of ourselves as being separate from or outside of nature, but thinking and writing about the natural world reminds me that we are actually a part of it. I really enjoy writing about animals in particular because they’re so much more honest than we are about what they need and want, and they have a completely different relationship to time and place than we do.

2. The novel positions an intimate portrait of Ro between the mysterious depths of the ocean and the tantalizing new frontiers of space. What led you to these two extremes? What role did research play in making them so real to the reader?

I’m both intrigued and terrified by the ocean and outer space. There’s so much we don’t know about both realms! I’m also similarly fascinated and confused by people like Ro’s father and her ex-boyfriend Tae, who give up so much of their lives to explore and chart the unknown. It takes so much courage and curiosity to boldly go where no one, or at least very few people, have gone before, and while part of me admires that impulse, I also can’t help but wonder about the people they might leave behind, like Ro. Regarding research, I did quite a bit when it came to writing about the day-to-day of Ro’s work at the aquarium—I watched a lot of YouTube videos to learn more about how aquarists interact with the creatures they care for, particularly octopuses, and read anything I could find online about giant Pacific octopuses in particular. But in terms of writing about the Bering Vortex, I mostly drew upon what I imagined a place like this might look and feel like. I liked the idea of it being a kind of no-man’s-land, transfigured by climate change and pollution into a zone outside the bounds of normal laws of nature and physics. I was also inspired by Karen Russell’s beautiful short story, “The Gondoliers,” which explores the seascape of a postapocalyptic, speculative Florida.

“I really enjoy writing about animals in particular because they’re so much more honest than we are about what they need and want, and they have a completely different relationship to time and place than we do.“

3. Ro’s childhood reverberates through the novel. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I was a voracious reader from an early age, and the moment I realized that books were things one could aspire to write, I was determined to become a writer myself. One early experience I recall was when I was quite young and got into trouble with my parents for cutting my hair one day, something I didn’t think I deserved to get in trouble for since it was my own hair, after all. I wrote a short story about the experience, and ended up writing about a little girl whose hair has the power to grow back magically, no matter how short she cuts it, and how this power becomes a huge burden to her. I forget how it ends, though I don’t think it had a happy ending. I showed the story to my parents, who were impressed enough (and probably a little disturbed, to be honest) with it to forget about scolding me. I think language has so much power when it comes to helping us organize and shape our thoughts and feelings, or, in younger me’s case, helping us to persuade or move others.

4. If you could claim any writers from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be?

I owe a huge debt to Maxine Hong Kingston and Amy Tan, whose seminal classics The Woman Warrior and The Joy Luck Club were among the first books I ever read that showed me a version of my own experiences as an Asian American woman and daughter of immigrants. Their facility and playfulness with language and their depictions of fierce and fearless women continue to inspire me every day. Mia Yun’s House of the Winds was the first American novel I ever encountered that depicted the life of a Korean family, and I treasure how beautifully it renders the complexities of family dynamics and how it travels between the boundaries of what is remembered and what is imagined. Edward P. Jones’s Lost in the City and Gloria Naylor’s The Women of Brewster Place are two incredibly important touchstones for me, for their keenly observed and deeply moving portraits of everyday life in the context of a specific community, which is something that really interests me as a writer. And the gentle weirdos and outsiders of Banana Yoshimoto’s work, especially Kitchen, have an enduring hold on me, because I’m always interested in the people who live on the fringes of society and deal with life’s loneliness in surprising, unexpected ways.

5. There are a lot of phases to publishing a book that not everybody knows about. Was there a point you would say was the most surprising or challenging for you as a debut author?

I think the most surprising thing for me as a debut author was realizing just how much additional work there is in putting out a book! Between handing in your manuscript to your publisher and publication day, there are so many intermittent stages and cycles of revisions, edits, copyedits, and proofreading, not to mention the work you also do with your marketing and publicity team to publicize the book, which can include brainstorming ideas for outreach, posting about your book on your social media channels, reaching out to your community and contacts about it, writing pieces in support of your book, etc. I’ve worked in book publishing before in both editorial and publicity, so not all of these stages were necessarily surprising for me, but it was still an adjustment being on this side of the desk, and realizing just how much being an author, especially in today’s day and age, can also feel like running your own business at times.

“I write and read to find connection, to feel a sense of recognition or discovery on the page, and that impulse, for me, is inextricably tied to hope.”

6. Sea Change reminds the reader that to love is to risk loss, and that “There’s no way to rehearse for heartbreak, no matter how much you might walk around expecting it.” And yet, the book and Ro’s capacity for growth are profoundly hopeful. How did you keep in touch with that thread of hope as you wrote?

I wrote the first draft of Sea Change in fall of 2020, when loss and heartbreak were very much on my mind. Writing through those feelings into a fictional narrative was incredibly cathartic, but it was also quite intense, and getting out of my own head helped—going for long walks, moving my body, or just reminding myself to pay attention to natural phenomena outside of the hamster wheel of anxiety in my own brain. I’m not a naturally optimistic person, but I can’t help but feel a sense of hope when I spend time outdoors in nature, or with the people I love, and witness firsthand our capacity, as humans, for resilience and care. As writers, I think we have to keep that thread of hope alive. I write and read to find connection, to feel a sense of recognition or discovery on the page, and that impulse, for me, is inextricably tied to hope. It’s such a wild and moving experience to encounter someone else’s words in the world, and to realize that they have managed to articulate an experience or emotion that you didn’t realize you shared in common. That type of encounter on the page makes me feel better able to hope for a better, more just and connected world.

7. What do you read (or not read) when you’re writing?

I’m pretty much always reading, no matter what type of writing project I have going on, and I’m one of those terribly unfocused readers that always has anywhere from five to ten different books going at once. I’m particularly inspired by writing that pays close attention to language, to the way sentences move and feel on the page, and to writing that feels deeply physical and embodied, and anchors me in a specific point-of-view or time and place. When I’m in the thick of a writing project, I also find it helpful to read or revisit books or pieces that I feel are emotionally in conversation with whatever it is I’m working on, because it helps to remind me of how I want a reader to feel when they’re reading my work.

8. What is your favorite bookstore or library?

The first bookstore I ever imprinted on was my beloved childhood Border’s (RIP) at the Garden State Plaza, the mall that I grew up near in New Jersey. I always felt so safe there, and once I got old enough to roam the mall on my own (a huge milestone in any suburban childhood) my mother could literally drop me off there for hours while she took care of her own shopping and errands, and still find me on the floor among the shelves later. I still feel that same feeling of safety and enchantment in every beloved reading space I frequent. I have far too many favorite present-day bookstores to choose from, but I do want to give a shout out to the Brooklyn Public Library at Grand Army Plaza, one of my favorite library branches in the city, where I love getting lost in the stacks and whose golden doors startle me with their beauty every time I see them. I also spent a lot of aimless, yet formative afternoons at the Paramus Library near where I grew up, with piles and piles of books in my arms, and I have such fond memories of those days.

“In some ways, it already feels like Sea Change belongs more to the world now than it does to me. Letting go and watching her begin her journey into the world is one of the most challenging yet beautiful things I have ever gotten to experience as a writer.”

9. Writing is often a private and intimate process. On March 28, Sea Change will also belong to readers. How have you prepared for that?

I’m both incredibly anxious and excited about it. To be honest with you, I don’t think I have prepared for it all that well! But my heart is very full when I think of all the love and support my book has received already. I’m deeply grateful for every kind note or review I’ve received from early readers of the book. In some ways, it already feels like Sea Change belongs more to the world now than it does to me. Letting go and watching her begin her journey into the world is one of the most challenging yet beautiful things I have ever gotten to experience as a writer.

10. Ro’s signature drink is the sharktini: gin, Mountain Dew, and jalapeño. Was this your invention? Will the sharktini be the drink of the summer for 2023?

It absolutely was my own invention, and I’m relieved and happy to say that after having made and tasted them myself, sharktinis are actually pretty good! I thought it would be funny for Ro to have a go-to drink that would be relatively easy to make at home, and the inclusion of Mountain Dew also felt like a fun callback moment for millennials like myself, given the association that that drink tends to have for our generation. My publisher, Vintage Books, actually made the sharktini the signature drink at a media lunch that they held in the lead-up to publication, which was extremely cool. And yes, I think we should call it now—Summer of 2023 is the Summer of the Sharktini!

Gina Chung is a Korean American writer from New Jersey currently living in Brooklyn, New York. A recipient of the Pushcart Prize, she is a 2021-2022 Center for Fiction/Susan Kamil Emerging Writer Fellow and holds an MFA in fiction from The New School. Her work appears or is forthcoming in The Kenyon Review, Catapult, Gulf Coast, Indiana Review, Idaho Review, The Rumpus, Pleiades, F(r)iction, and Wigleaf, among others, and has been recognized by several contests, including the American Short(er) Fiction Contest, the Los Angeles Review Literary Awards, and the Ploughshares Emerging Writer’s Contest.

Gina Chung is also a former member of the Communications team at PEN America.