The PEN Ten: An Interview with Fatimah Asghar

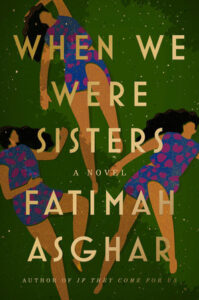

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Associate Director, World Voices Festival and Literary Programs, Sabir Sultan speaks with Fatimah Asghar, author of When We Were Sisters (One World, 2022). Amazon, Bookshop. Fatimah will be on a national book tour starting October 17th.

1. You are a poet, a director, a screenwriter, and a novelist – how do you know when a story requires a certain form? Do you find one form more natural than the others?

I think that, like everything, my idea of form is relational. For example, I’ve been writing poems for fifteen years now, and probably more seriously for eleven years. So I’ve been in a relationship with poems for eleven years. Right now, I’m noticing that my relationship to poetry is very different from my relationship to it when we first started—when I was honeymooned by it and completely obsessed. I feel now my relationship to poetry is one I know is there, that I can depend on, but where I also see the poems coming slower to me. For example, in the last two years I think I’ve written less than seven poem drafts. Whereas that might have thrown me into an identity crisis a few years ago, right now I just feel comfortable in that relationship and how it’s revealing itself to me. I trust my relationship to poetry even as it ebbs and flows—is the baseline of love where my writing stems from, and it is what allows me to explore other genres. I’ve only had a relationship to fiction for four years, when I first started writing When We Were Sisters. I think the same is true for directing. Those forms are a lot newer to me, they’re constantly surprising me and showing me what is possible.

As for how do I know what is what? I listen.

2.In When We Were Sisters you make use of poetic devices and verse throughout the novel. What led to that choice? Could verse accomplish something prose could not?

This was an incredibly difficult book to write and quite honestly one of the hardest artistic projects that I have undertaken. My friend (and incredible accomplished artist) Krista Franklin, told me that I needed to write the book however it was coming, even if I needed to cross things out or erase or scribble. And so, that’s what I did. I wrote the book how it came, and I worked to not be self-conscious of the myriad ways that it needed to reveal itself.

“I think it’s important for us to keep making stories that actually have nuanced portrayals of the communities that we come from, and also break the burden of needing our voices to be ‘representational’ and instead just be able to be.”

3. Much of the novel takes place in the apartment building Kausar’s uncle owns and that she and her sisters reside in. Why did you choose that space as the main setting?

So much of this novel to me revolves around what is unsaid, what is happening behind closed doors. And so therefore, so much of the novel takes place in the house because that’s where things are happening, where they’re alone, and where they are making a life for themselves outside of the eyes of everyone else.

4. Kausar and her sisters, Aisha and Noreen’s, lives are so entwined in each other growing up, but as they grow older they each build private lives from the others. How do they navigate love and loneliness in the context of each other?

I think that’s the thing about the siblings in this book—at one point they are all so close and enmeshed it’s as though they share the same skin. And as life goes on everyone moves into their own lives. We mostly see this from Kausar’s perspective, who struggles with wanting freedom and then also navigating the loneliness that comes from her self-estrangement, and the deep love that she feels towards her sisters, even from afar. Kausar’s response to navigating this—not only with her sisters but with her romantic partners—is to disappear. To move far away. And because of that, she extends her own loneliness out more than she needs to.

5. Through If They Come for Us, Brown Girls, Ms. Marvel, and When We Were Sisters you have created a breadth of works that depict Americans of South Asian descent. What would it have meant to you to have stories like yours available to you when growing up?

Thank you so much, that’s kind of you. I did not create Ms. Marvel though, I wrote on the show, but she was a character that was in existence long before I helped work on her.

I know that if I had stories like this growing up it would have changed my life. I never got to see South Asian or Muslim people in roles on TV or even that much in literature. When I did they were often stereotypical, or reduced to being nurses, doctors, gas station workers or terrorists. That’s so harmful when the majority of the stories that have people who look like you don’t look anything at all like your family, friends or community. I think it’s important for us to keep making stories that actually have nuanced portrayals of the communities that we come from, and also break the burden of needing our voices to be ‘representational’ and instead just be able to be.

“What happens when individuals actually listen to their bodies rather than impose their own wills over it? But sometimes my characters are not at that point yet, they’re on their way there. So you see them at various stages of listening and not listening.“

6. Throughout your works, and in When We Were Sisters you explore the relationship between individuals and their bodies. What interests you about the body?

The body is everything. Historically I’ve had a hard time with my body, because of the kinds of violence it has faced. It’s been easier for me to dissociate from my body rather than to fully feel it. At the same time, nearly everything is colored by the body—how you move through the world, how people treat you and interact with you, how you interact with yourself. And so even in the moments that I’ve tried to erase myself from my body or dissociate from it, it still remains a consistent presence that refuses to be erased.

And so over the last few years I’ve really been trying to be kinder to my body and to develop a relationship to it that feels good. And to listen to it. And I think that’s why that’s so important to explore in my work: what happens when individuals actually listen to their bodies rather than impose their own wills over it? But sometimes my characters are not at that point yet, they’re on their way there. So you see them at various stages of listening and not listening.

7. What has felt like the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I do think this book is one of the most daring things I’ve done. As for something I can take back, I don’t think so, but there are definitely things that I have outgrown. There’s a lot of stuff that I’ve written that I look back on and I’m like—oh yeah, I remember when I felt that way, and now I see things differently. But I think that’s kind of the thing when you treat yourself with kindness; you just are able to be like—yeah that’s where I was at that moment and that’s what I had the ability to do and articulate. And I learned from that. Now, I’m at a different place. And that can be beautiful. That can be a: wow, look how much I’ve grown rather than a: wow look how dumb I was.

8.How did you find out When We Were Sisters was longlisted for the National Book Award in fiction? How did you feel?

I was in LA at the time and so I was on Pacific Time and it was 7am when the news came out. I woke up an hour and a half later and my phone was like blowing up—I had many missed calls from my friends and editor and agent and like 200 text messages, mostly from my group chats. And I was like very groggy and like—what is going on? It took me a while to understand what was happening—to be honest I don’t know that I still fully understand it—but I feel really humbled and grateful and just very honored to have the book recognized in this way.

“There’s only things that you can write. Find those things. And it might not be until much later in life. And that’s okay.”

9. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

It’s so different honestly! Sometimes I’m working on a project and it’s all I’m doing all day, or for weeks or for months. With the novel it was: wake up and write every morning, try and edit in the afternoon. When I’m on set for directing sometimes it’s 12 hour days. It can be a lot. And sometimes I’m just like—no. I can’t. And I don’t.

10. What advice do you have for young writers?

You have to just practice, and you have to get good at listening to your own voice and developing out your own voice. There will be moments where you might stray from that, and that’s okay—you don’t need to beat yourself up over it. But you do need to just gently guide yourself back to your own listening. There’s only things that you can write. Find those things. And it might not be until much later in life. And that’s okay.

Fatimah Asghar is an artist who spans across different genres and themes. Their first book of poems If They Come For Us explored themes of orphaning, family, partition, borders, shifting identity, and violence. Along with Safia Elhillo, they co-edited Halal If You Hear Me, an anthology for Muslim people who are also women, trans, gender non-conforming, and/or queer. The anthology was built around the radical idea that there are as many ways of being Muslim as there are Muslim people in the world. They also wrote and co-created Brown Girls, an Emmy-nominated web series that highlights friendship among women of color. Their debut lyrical novel, When We Were Sisters, explores sisterhood, orphaning, and alternate family building, and is forthcoming October 2022. While these projects approach storytelling through various mediums and tones, at the heart of all of them is Fatimah’s unique voice, insistence on creating alternate possibilities of identity, relationships and humanity then the ones that society would box us into, and a deep play and joy embedded in the craft.