The PEN Ten: An Interview with Emma Ramadan

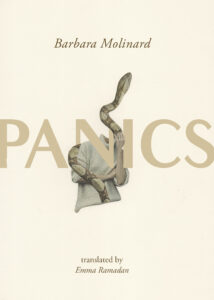

Panics, or Viens in the original French, is the only book Barbara Molinard published. She was a fervent writer who destroyed all she wrote–this recueil survived as a result of the unrelenting insistence from her husband Patrice Molinard and friend Marguerite Duras that she ought to share her work. These stories, translated by Emma Ramadan, winner of the 2021 PEN Translation Prize among other accolades, explore the doorways between the absurd and the mundane, between the conjured and the lived. Emma’s translation not only made the text accessible to English readers for the first time but sparked a new edition of Viens, allowing French readers to discover a work that may have otherwise been lost.

In conversation with Lili Stern, Literary Awards Assistant, for this week’s PEN Ten Emma Ramadan discusses Molinard’s work and the art of translation.

1. Emma, you have such an extended and impressive portfolio of translations, most of which are novels when it comes to full-length works. Did you find that there was a difference in translating a collection of short stories? Were there any stories in particular that you felt drawn to or that posed any difficulties?

Translating short stories is different from translating a novel because there is no arc, no build, no resolution. It’s many tiny worlds captured in one book, and as a translator I try to find the through-line, the quality that makes them resonate with each other and exist in conversation with each other, and really lean into that thing. In Panics, it was the shared experience of Barbara Molinard’s characters, that they are all slightly off-kilter and seem unable to fit themselves inside of the same reality as everyone else. It was also Molinard’s style, of course— her tone, the frantic, obscured narrative voice, the small caps and repeated semicolons. “Taxi” and “The Meeting” were the most challenging stories to translate because they didn’t quite fit into that mold—but that is also what brings vibrancy to a collection, when they cannot all be neatly mapped onto a particular mode of storytelling.

2. Could you talk a bit about Barbara Molinard and writing as an exorcism of sorts?

What’s interesting about Barbara Molinard is that it seems writing was meant to be a form of exorcism for her, that is likely what she wanted or hoped for, but it never quite worked. She tore up her writing and began again, and whatever it was that she was trying to expel remained. Maybe it is too tall a task to rid ourselves of something simply by putting it down on paper. Annie Ernaux has talked about writing as a form of experiencing or living the event, rather than eliminating or expelling it (I am very much paraphrasing from memory here), and maybe that was the case for Molinard as well.

“There is something in these stories that is often written about but rarely captured with such poignancy—the frightening dips from reality to irreality, from normalcy to utter alienation, the hinges suddenly coming off of your world. I wanted that exact feeling to be accessible to readers in English.”

3. These stories can really best be described as haunting. What was it like for you to read this for the first time? Did you always know this was something you wanted to put into English?

I felt very haunted by these stories before I had even read them; from the time I read Marguerite Duras’s preface to the book and knew they existed, I felt I needed to read them, I had an inkling that I would catch a vague glimpse of myself in them, and when I finally had the book in my hands and read the first story, “The Plane from Santa Rosa,” my hunch was confirmed. More broadly, there is something in these stories that is often written about but rarely captured with such poignancy—the frightening dips from reality to irreality, from normalcy to utter alienation, the hinges suddenly coming off of your world. I wanted that exact feeling to be accessible to readers in English.

4. Could you speak a bit more about the new French edition of Viens?

Éditions Cambourakis in Paris, a wonderful publishing house that publishes a lot of work in translation, released the new French edition of Viens to coincide with the English-language publication in September 2022. The book’s cover is a drawing by Molinard herself, and this is the first time the book has been in print in French in decades. I know it touched Molinard’s daughters enormously for their mother’s work to be back in print. Perhaps other readers will stumble upon it, as I did, and find it changes their lives in some way, too.

5. In the translation community, there seems to be a lot of discourse over translators’ names being excluded from book covers, which came up quite a bit during deliberations for our awards. I’d love to hear your thoughts on it and on the necessary recognition of the translator’s work.

As many others have said before me much more articulately, putting a translator’s name on the cover doesn’t fix all the other issues surrounding how literary translation work is undervalued and undermined, but it is a cost-free and effective way to acknowledge the role and importance of the translator. The myth that “translations don’t sell” and that the average reader will turn their nose up at a book if they see it is a translation has been disproven time and time again with various bestsellers (Elena Ferrante, Stieg Larsson, Peter Wohlleben, Haruki Murakami, among others) and buying into that idea only perpetuates the idea, when it would be quite easy instead to unravel and dispel it. It’s time to move on from that nonsense now—we should all be doing our part to rob that myth of its power.

“Putting a translator’s name on the cover doesn’t fix all the other issues surrounding how literary translation work is undervalued and undermined, but it is a cost-free and effective way to acknowledge the role and importance of the translator. The myth that “translations don’t sell” and that the average reader will turn their nose up at a book if they see it is a translation has been disproven time and time again.”

6. We receive a lot of questions about how to “make it” in this field. What is some advice you’d give an aspiring translator?

Choose and pitch projects that speak to you personally and urgently. If you care about it, others will too. Don’t try to pick a book simply because the author has an impressive resume, or because it won an award—none of that matters when you’re on draft 8 and your 30th pitch letter. What matters is why it moved you in the first place, and your belief that it will move others. That’s what makes all the time and effort worth it. It took me nearly two years of pitching Panics to place it, and it was because of my passion for the book that I was able to be patient and not lose faith.

7. You won the 2021 PEN Translation Prize for A Country for Dying: A Novel by Abdellah Taïa. How did this recognition affect you and your work?

To be recognized by an organization with the caliber and reputation of PEN is an enormous accomplishment and point of pride for me, and has tangibly translated (pun intended) into more translation work and the ability to get the ear of more publishers for projects I’d like to pitch. More importantly, I was thrilled for Abdellah Taïa that his wonderful novel was recognized—it got the book into the hands of many more readers, and for that I am very grateful. That is the ultimate goal of translation, after all.

8. What, to you, is a good translation?

I won’t speak to “good,” because there are many kinds of “good,” but after more than ten years of translating, I have decided my favorite kind of translation is one in which you can feel the translator has lived inside of that book, and that book has lived inside of them. When a translator is able to discover something of themselves through the book, when they are better for having translated it and the book is better for having had them as translator. When the two feed and feed off of each other.

“My favorite kind of translation is one in which you can feel the translator has lived inside of that book, and that book has lived inside of them. When a translator is able to discover something of themselves through the book, when they are better for having translated it and the book is better for having had them as translator.”

9. Do you have any exciting projects being published that we should keep an eye out for?

My most recent translation is Moroccan author Kaoutar Harchi’s autobiography As We Exist, published by Other Press, and my next translation is Lebanese author Lamia Ziadé’s personal and historical narrative My Port of Beirut, forthcoming May 2023 from Pluto Press.

10. You’ve said before that you’re obsessed with Marguerite Duras. How did this literary love affair begin?

In my senior year of high school, my AP French Literature class had to read Duras’s novel Moderato Cantabile and absolutely none of us understood anything of what was going on. Our poor French teacher kindly wrote summaries of each chapter for us. Even then, I felt so far away from comprehending it, and yet if I squinted, I thought I caught a glimmer of myself in the main character, and in the writer who had created that character. I knew I needed to find a way to get close to that part of myself, through Duras’s writing. Today I’m teaching that book (in the English translation by Richard Seaver) to high schoolers in a real full-circle moment, and I identify with the main character less but admire and savor the novel just as much—for what Duras does with motif and language, how she wields subtlety to lay bare something so extreme. And I’m learning new things about it from my students, too, which is really a dream.

Emma Ramadan is an educator and literary translator from French. She is the recipient of the PEN Translation Prize, the Albertine Prize, two NEA Fellowships, and a Fulbright. Her translations include Abdellah Taïa’s A Country for Dying, Kaoutar Harchi’s As We Exist, Barbara Molinard’s Panics, and Marguerite Duras’s The Easy Life.