Temperature Check, Vol. Nine: The Election Issue

A responsive series from PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, featuring original creative reportage by incarcerated writers, accompanied by podcast interviews with criminal justice reform experts on the pandemic’s impact in United States’ prisons.

Volume 9.0 Table of Contents

- Introduction: Frances Keohane

- Dispatch: Corey “Al-Ameen” Patterson

- Podcast: Manhattan DA Candidate Lucy Lang

- Advocacy, Action and Resource Roundup

Introduction To Volume 9.0:

The Election Issue

Dear Readers,

Our country prides itself on its symbiotic social contract: an agreement between state and individuals, whereby citizens who breathe American air; who live or work or raise their families on American soil; who support this country financially, emotionally, and culturally are in return granted certain rights. One of these rights is the ability to vote, to have a voice in what might otherwise seem like a political void, to ensure that those in power uphold and maintain the integrity of our social quilt.

Yet today, over six million American citizens are stripped of their right to vote through felony disenfranchisement laws. And, more alarmingly, more than half of these individuals have already completed their sentence.

This introduction to issue 9 of Temperature Check takes up a bit more space to inform on the historical and modern consequences of voter suppression in carceral settings.

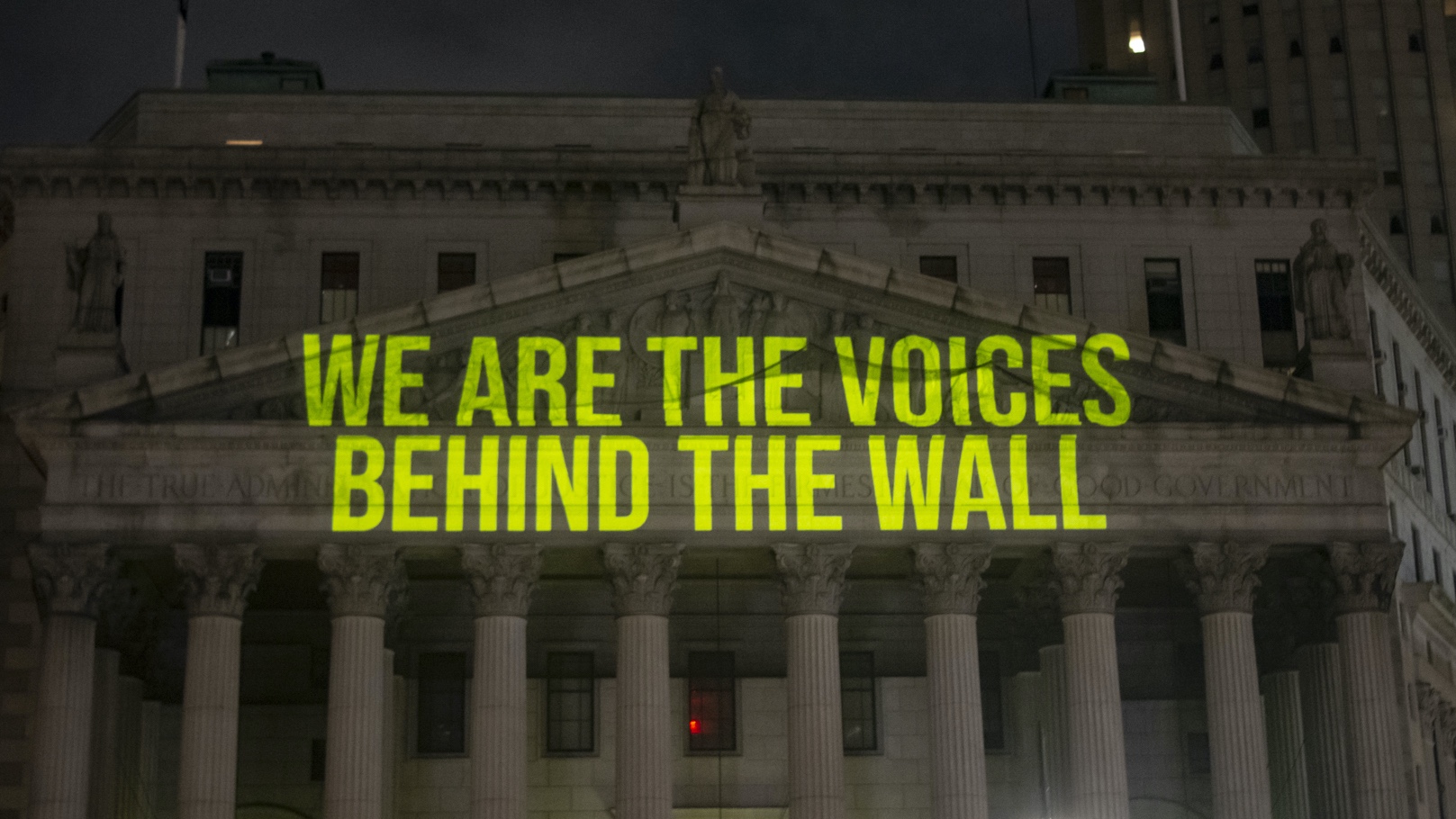

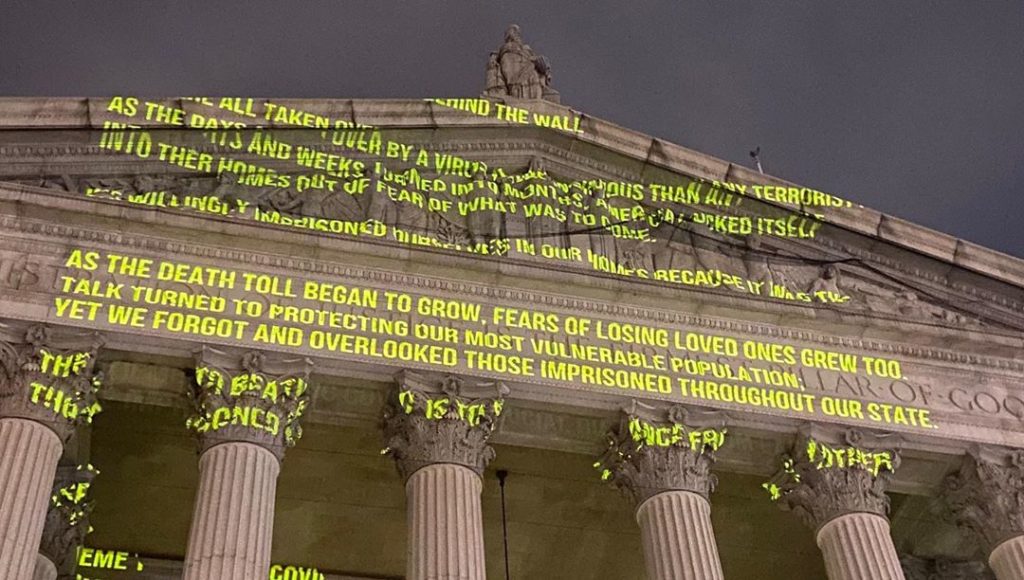

Writing projected on the New York State Supreme Court building in Manhattan. Photo by Chemistry Creative

Voter disenfranchisement has deep and racialized roots in our country. It gained popularity as a political weapon after the Civil War, as states—particularly those in the South—enacted felony disenfranchisement provisions that passed strategically through the cracks of the newly-ratified 14th and 15th amendments. These laws fundamentally and intentionally dampened the political power of newly-enfranchised racial minority groups.

These racialized laws and their consequences are still pervasive today. Only two states, Maine and Vermont, allow citizens behind bars to vote. Thirty-one states continue to disenfranchise people after their release from prison, restricting those on parole or probation—who are living, working, paying taxes, and contributing to communities across America—from voting.

Many states also reserve the right to vote only for those who can afford it—a practice declared unconstitutional by numerous civil rights organizations—espousing laws that require individuals to pay all legal financial obligations before regaining the right to vote.

One such legal battle is being waged now in Florida. There, in November 2018, Amendment 4 passed with overwhelming support, restoring voting rights to 1.4 million formerly incarcerated Floridians. Less than a year later, in June 2019, Governor DeSantis signed into law Senate Bill 7066, which prohibited returning citizens from voting until they paid off all legal financial obligations imposed by a court before conviction.

And just last month, after an arduous legal battle concerning the bill’s constitutionality, the Eleventh Circuit court upheld DeSantis’s decision. With major consequences for this year’s election, the act disenfranchises more than 774,000 Floridians who are otherwise eligible to vote. Explore this edition’s advocacy section to see how you can help with voter enfranchisement—in Florida, and in your own state.

Much like prisons, voting laws across the country are far from uniform. Each state has its own regulations, most of which are convoluted and poorly understood. Confusion among voters and officials alike about individual voting rights has led to widespread de facto disenfranchisement, and the jail system is among the most stealthy perpetrators.

To learn more about voter disenfranchisement in jails, read Corey Al-Ameen Patterson’s essay, “An Act to Increase Voter Registration and Participation,” featured below.

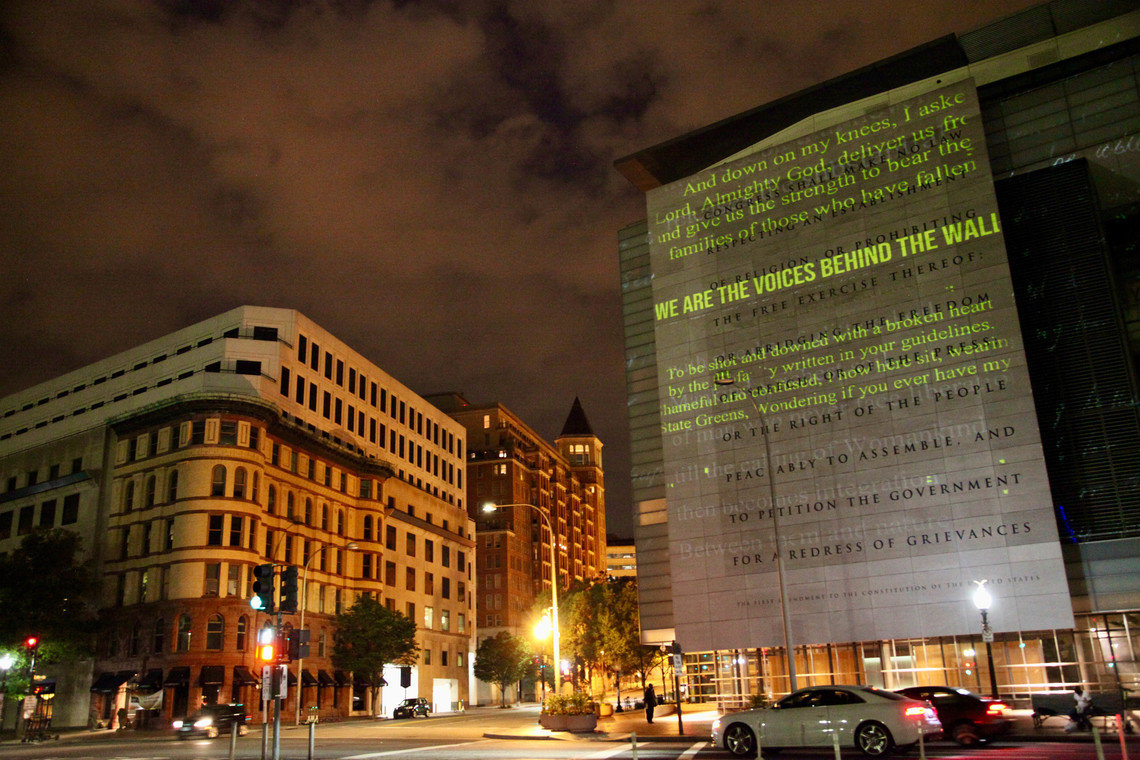

A projection on the former Newseum building in Washington, D.C. Photo by Chemistry Creative

Given the nearly ubiquitous practice of disenfranchising those behind bars, it seems strange to count incarcerated men and women in a district where they have no political voice. But that’s exactly what the federal government does, roping incarcerated individuals into the population counts of the districts where the prison is located, rather than the communities in which they grew up or would now choose to live.

“Prison gerrymandering,” the term for this method of conducting the census, has considerable political and ethical implications. Rural, predominantly white prison towns receive extra political representation because their population numbers are augmented by those incarcerated—a disproportionate number of whom are Black and Latinx, and come from urban areas.

Though the national scale is certainly an arena of great importance, it is often the elections at the local level that determine the trajectories of our day-to-day lives. In this edition of Temperature Check, we spoke to Lucy Lang, a candidate for Manhattan district attorney. She reminded us of the importance of voting in local elections and affirmed that indeed, felony voter disenfranchisement laws may perhaps have the greatest consequences in these battles for local political turf.

As Ms. Lang emphasizes, it is in these local elections that we cast ballots for the legislative, executive, and judicial authorities that control the gears of the justice system. Thus, it is even more crucial that justice-involved individuals, who have experienced the system firsthand, be able to have and use their political voice in these elections.

So, if you, reader, have the ability to make your political voice heard, use it—not just for yourself, but also for the six million others who cannot.

Thank you for engaging.

In solidarity,

Frances Keohane, PEN America

Prison and Justice Writing Fellow 2020

The PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Team:

Caits Meissner, Program Director

Robert Pollock, Program Manager

Mery Concepción, Volunteer Coordinator

Frances Keohane, 2020 Program Fellow

Nicolette Natale, Works of Justice Podcast Producer

Jenna Bao, Fall 2020 Program Intern

Dispatches From Inside

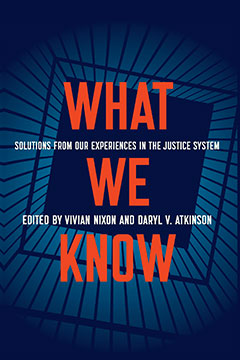

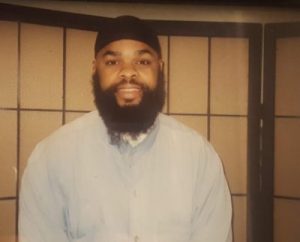

Our election issue dispatch comes from Corey “Al-Ameen” Patterson, whose essay, “An Act to Increase Voter Registration and Participation,” appears in What We Know: Solutions from Our Experiences in the Justice System. This book, recently published by our friends at The New Press, features specific policy suggestions for criminal justice reform by those closest to the issue: currently and formerly incarcerated writers, scholars, and leaders. We’re proud to share that the book is co-edited by PEN America Writing For Justice Fellow Vivian Nixon, alongside Daryl V. Atkinson, and features contributions from four other members of our fellowship and Prison Writing Program.

Patterson was born and raised in Boston, MA. At MCI-Norfolk, where he is currently serving time, Patterson is vice-chair of the African American Coalition Committee. A strong advocate for the voting rights of incarcerated people across the country, Patterson coordinated a coalition of prisoner suffrage advocacy groups to push for a 2020 ballot initiative that would fight against de facto disenfranchisement in jails. In his essay, Patterson shares his own experience with the suppression of his suffrage and details how his bill, “An Act Increasing Voter Registration and Participation and to Help Prevent Recidivism,” will prevent others from facing the same.

Patterson was born and raised in Boston, MA. At MCI-Norfolk, where he is currently serving time, Patterson is vice-chair of the African American Coalition Committee. A strong advocate for the voting rights of incarcerated people across the country, Patterson coordinated a coalition of prisoner suffrage advocacy groups to push for a 2020 ballot initiative that would fight against de facto disenfranchisement in jails. In his essay, Patterson shares his own experience with the suppression of his suffrage and details how his bill, “An Act Increasing Voter Registration and Participation and to Help Prevent Recidivism,” will prevent others from facing the same.

An Act to Increase Voter Registration and Participation

by Corey Al-Ameen Patterson

Around seven weeks before the 2008 presidential election, I found myself in the back of a Suffolk County prisoner transport van headed to the Boston Municipal Court Department, Dorchester Division, to be arraigned on new criminal charges. Though I had bail money, it didn’t matter. Because I was already out on bail, a new arrest gave the court full discretion to revoke the bail I previously posted and detain me, usually no longer than a period of sixty days. In routine fashion, as I expected, the judge took full advantage of this discretion and sat me down for the full two months. Come election night, the only silver lining was that my cell door was positioned directly in front of the television suspended from the wall in the recreation area. It was there, from behind the glass window on my cell door, I witnessed Barack Obama become the first black man to become president of the United States. Whenever I recall this (and I do quite often), I cannot help feeling ashamed that I lost my opportunity to cast a ballot for the country’s first black president—especially as a black man myself. What makes looking back at this experience most painful is knowing now, as I did not know then, that I was legally still eligible to vote even while incarcerated.

Fast forward ten years later, Massachusetts State Rep. Russell Holmes visited MCI-Norfolk, and sat in our African American Coalition Committee (AACC) board meeting. After the meeting he was so impressed with the vision, solidarity, and professionalism of our group that he promised to file the legislation we planned to draft. The civic engagement department, headed by Derrick Washington, came up with the idea of proposing legislation that would make criminal detention facilities responsible for helping eligible voters in their custody obtain absentee ballots. As fate would have it I was assigned the task of drafting the legislative text. I had missed the chance to vote for Obama myself, but this was my chance to make a difference for many others who would otherwise have identical experiences in the future. This legislation would raise voter participation among incarcerated citizens, especially for those in pretrial detention centers, since these facilities house the highest number of eligible voters. In 2008 I was eligible to vote—I was twenty-one, a U.S. citizen, and a pretrial detainee yet to be convicted (actually I was never convicted in the case the judge revoked my bail on because the charges were eventually dismissed)—but I didn’t know it. Think about all the incarcerated citizens nationwide who don’t know they can vote. If all detention facilities were obligated by law to provide new detainees with knowledge about their voting rights during orientation and help them obtain absentee ballots, just as they are obligated to administer TB tests or flu shots, without a doubt most people would take advantage.

Continue reading “An Act to Increase Voter Registration and Participation”

Works of Justice Podcast Interview: Manhattan DA Candidate Lucy Lang on the Importance of Local Elections

To learn about how local officials within the criminal justice system can be actors—if unlikely ones—in expanding the rights of justice-involved individuals, we spoke to Lucy Lang.

The former director of John Jay’s Institute for Innovation in Prosecution and a candidate in the race for Manhattan district attorney, Lang has a reputation for being a leader in reform. In this episode, she helps us understand the scope and significance of the district attorney’s work—particularly in the era of COVID-19, when the leadership of criminal justice officials is paramount in ensuring the safety of individuals behind bars and of their communities on the outside. In doing so, Lang reminds us of the importance of voting in local elections. Echoing our own mission at PEN America, Lang also speaks about the intersection of public policy and writing: how storytelling can be a tool for advocacy and empowerment.

Listen to the 40-minute conversation on our Works of Justice podcast:

Click here to access the transcript or listen on Apple Podcasts Spotify Google Play

“The Writing on the Wall” art installation on the New York State Supreme Court building in Manhattan. Photo by Chemistry Creative

Advocacy, Action and Resource Round-Up

FELONY DISENFRANCHISEMENT LAWS

-

Learn about and support the Democracy Restoration Act, federal legislation that seeks to restore voting rights in federal elections to disenfranchised Americans. Contact your representative and both of your senators, urging them to co-sponsor H.R. 196 and S. 1068.

-

Learn where your state currently stands in its felony disenfranchisement laws, and support legislation in your state to restore voting rights. For example:

- California: Proposition 17, which you can vote for in November, proposes a state constitutional amendment that would restore voting rights to over 50,000 Californians on parole for a felony conviction.

- Florida: Learn about and participate in initiatives undertaken by the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, a powerful grassroots organization “dedicated to ending the disenfranchisement and discrimination against people with convictions.” Help Floridians exercise their constitutional right to vote by contributing to pay off their court debt.

- New York: Support A. 4987 and S. 1931 legislation, which, like Proposition 17 in California, would restore voting rights to individuals on parole.

- Washington: Support HB 2292 and SB 6628 legislation, which would automatically restore voting rights to individuals on community supervision (probation and parole).

-

Find and contact state and federal representatives, and let them know that you believe felony disenfranchisement laws are anti-democratic and discriminatory.

-

Volunteer with local/community organizations that help with voter registration, that advocate for changes to and/or the eradication of felony disenfranchisement laws, and/or that work to educate people with convictions about their rights. Check your local ACLU chapter or organizations such as All Voting is Local.

PRISON GERRYMANDERING

-

Learn about where your state currently stands in its prison gerrymandering laws, and discover if your state has an active campaign against prison gerrymandering on the Prison Policy Initiative’s Prison Gerrymandering Project’s Take Action page.

-

View your state’s active legislation concerning prison gerrymandering, and find and contact state and federal representatives to urge them to support the legislation.

-

Subscribe to the Prison Policy Initiative’s Prison Gerrymandering Newsletter to stay informed about the issue.

A page from Matthew Wilson’s graphic novel on the Department of Justice’s Robert F. Kennedy Main Justice Department Building in Washington, D.C. Photo by Chemistry Creative

GENERAL ELECTION

-

Become a poll worker, ensuring the integrity of the election. The record shortage of poll workers this year could force the closure of many voting precincts, causing confusion, long voter lines and delays, and reduced voter turnout.

-

Help increase election turnout in 2020 by handwriting letters to voters in the state of your choice through Vote Forward.

-

Educate yourself about who is on your local ballot, and what they stand for on Ballotpedia.

DISTRICT ATTORNEYS

-

Learn more about the district attorney’s role through the ACLU’s “District Attorney 101: The Power They Wield” or their California campaign, “Meet Your DA.”

-

Learn from public defenders about how decisions made by district attorneys impact the citizens in their communities.

-

Engage with Community Justice Exchange’s “Abolitionist Principles & Campaign Strategies For Prosecutor Organizing” to learn how abolitionists electorally organize for “non-reformist” reform prosecutors.

COVID-19 IN PRISON

-

Learn about the issues related to the spread of COVID-19 behind bars in the Prison Policy Initiative’s comprehensive COVID-19 and the criminal justice system informational page.

-

Explore the COVID-19 resources page on the Prison Advocacy Network’s website, where there is ample information about appeals, compassionate release, and ways for you to get involved, regardless of your professional capacity.

-

Mourning Our Losses is an organization that compiles obituaries for those who died of COVID-19 in prisons and jails—both incarcerated individuals and correctional officers—to “restore dignity to the faces and stories behind the statistics of death and illness from behind bars.” Read the moving obituaries.