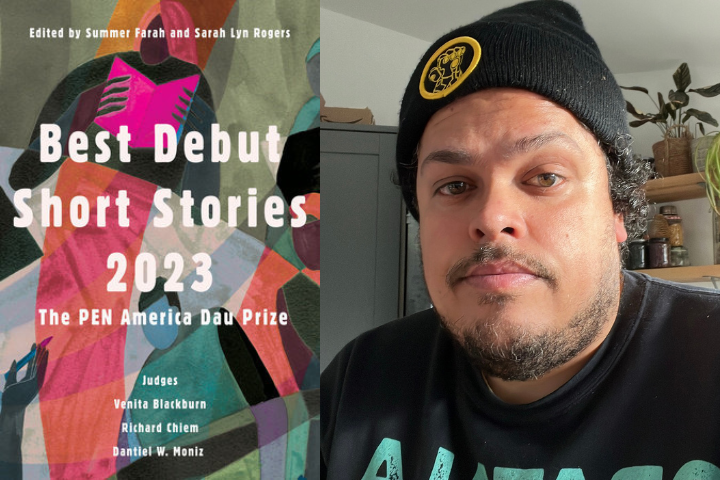

Stephenjohn Holgate | 2023 PEN/Robert J. Dau Prize Winner

In the coming weeks, we will feature Q&As with the contributors to this year’s Best Debut Short Stories anthology, published by Catapult. These stories were selected for the 2023 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers by judges Venita Blackburn, Richard Chiem, and Dantiel W. Moniz.

Stephenjohn Holgate was born in Port Antonio, Jamaica and moved to the UK when he was eight years old. After reading English Literature at Oxford University, he completed an MA in Classical Acting and worked as an actor for a number of years. He is a member of Writing West Midlands Room 204 development scheme and is one of the winners of the Bridport Prize’s first Black Writer’s Residency. His short story “The Skull of an Unnamed African Boy” was longlisted for the 4th Estate 4thWrite Short Story Prize 2023. He is in the process of relocating to Aotearoa/New Zealand while looking for a home for a collection of short stories and a novel.

“Delroy and the Boys” was originally published in West Trade Review.

Here is an excerpt:

When I reach round to the ballroom where everything taking place I see Tony and Earl lean up against one of the pillars looking into the main area and Tony smiling big big. So I lean up my bicycle by the coconut tree and go over to them. When I look in is a troupe of dancers doing something that I think is supposed to be kumina. Black, gold and green costumes, woman with their hair tie up and hands holding up their skirt. But they look bored. Really bored. And I can see why. The musician them just going through the paces, no liveliness on the drums at all at all. Like the drums themselves drink a white rum and done for the night. When I look over on the musicians I see Bongo there betwixt everybody, looking foolish.

What inspired you to write “Delroy and the Boys”? Where did the idea come from?

It was the start of the pandemic and I was playing a lot of Capoeira Angola music, berimbau, pandeiro, atabaque, and I had just got back into writing fiction. So I was thinking about music and I was reminded of going to a Jolly Boys concert in Shepherds Bush, London. The Jolly Boys are a mento group from the same little corner of Jamaica that I am from and they have been performing for years with new members coming and going. Most of the members were in their 70s and 80s when I saw them. They had found international fame late in life with a mento version of Amy Winehouse’s Rehab. After the concert, I ended up backstage and having a drink with one of the original members of the group, Joseph “Powda” Bennett, who was reserved until realizing we knew people in common. Then he became talkative and warm. Years later I would see a video of him when he was much younger being interviewed and there was yet another side to him on display: tough, thoughtful, very serious about the music he was playing.

This struck me as something really interesting: continuing to pursue an art form with no view of the future, with nothing more than a strong belief in the importance of that craft and work. I had seen a similar thing with great musicians in Capoeira. With this idea of the importance of art I wanted to explore the little victories in life. Because a world tour is rarely on the minds of most musicians, but a moment of success in the face of danger? Those moments are special.

At the same time Jamaican music has always been outward looking: from the sound systems of the 1950s playing American Rhythm and Blues records that people brought back after they’d gone to perform migrant farm work, to the fact that I’ve heard reggae versions of almost every pop song imaginable, so I wanted to explore that in some way. A thing that often surprises people is that Jamaicans love country music. Kenny Rogers is very popular. I wanted to include something that acknowledged that.

Tell me about how language, music, and community come together in this story.

It’s difficult to convey just how pervasive music is in the daily life of Jamaica. I’ve just been for a walk through the streets of Birmingham and there are few cars playing loud music, no sounds of speakers from corner shops, no-one walking the street singing to themselves. Not many people walking at all. Whereas music in Jamaica is at least as important as language. I wanted that to be felt in the piece. And after eighteen years or so of playing Capoeira music, I’m really aware of how important each member of a band is, how they have to operate as a little community, but also, how there are often at odds with each other even as they create something that is enjoyed or experienced as something more unified. I’m quite interested in the tensions of these things, how we are pulled in many different directions as the different bits of ourselves, musician, worker, lover and so on, come into conflict.

And the language of mento, the language of Powda when he relaxed into speaking with me, the language of Jamaicans in my family thirty or forty years on from leaving the island to live in Florida or Canada or the UK is Patwah. So even when we try to bridge the gaps between Patwah, Jamaican English, and other world Englishes, there is a Jamaican syntax than asserts itself and organizes our thoughts, one that affects the cadence and structures of our stories and I wanted to explore that and how it might inform how the story was told.

What do you hope readers take away from your story?

A sense of joy in the little victories in life. Life is hard and difficult and relentless and it’s easy to miss just how ridiculous it is. So, I’d like them to take away laughter and joy. Alongside love that’s the best of what we have in our short time.

What advice would you share with aspiring writers?

Keep writing. It seems silly, but it’s probably the most important thing. Keep writing and finish your writing. I always wanted to write fiction, but after doing a degree in English I felt as though I was sort of unworthy of it, or that the words I had and the order in which I would arrange them would be insufficient. It took me twenty years to get over that block, but I feel as though I am well over it now.

How has the PEN/Robert J. Dau Prize affected you?

It came at a necessary moment. I’d started writing again and was having little external validation. I was quite happy with how the writing itself was developing, but I also wondered if I was engaging in an act of self-delusion. But winning the prize has put me in touch with a group of wonderful writers and I no longer feel deluded. There’s a sense of validation.