Shannon Hale’s heartfelt children’s book Pretty Perfect Kitty-Corn has one simple message: Everyone makes mistakes, and we all deserve to be loved regardless.

The message is delivered to young readers by two best friends, Unicorn and Kitty. Kitty is working on a portrait of Unicorn when Unicorn accidentally sits in some paint, but Kitty shows him that it’s no cause for shame.

Recently, the book caused quite a stir in a Texas school district because Unicorn, a male character, is depicted with eyelashes and a purple mane, and because the story features his “paint bum.” The controversy came as a shock to Hale, who had set out to write an innocent, lighthearted tale about friendship. She had no intention of making a point about gender in Pretty Perfect Kitty-Corn — though this wasn’t the first time in her career that she’s had to confront the discomfort that arises when boys have feminine traits or interests.

In conversation with PEN America, Hale talks about pushing back against that discomfort and encouraging boys to read books that center female characters. She explains how she imbues all of her books with compassion and why her experiences as a mother have made her only a fiercer advocate for the freedom to read.

Hale knows that creators of children’s literature and those pushing for bans can’t agree on much. Still, she thinks that both groups share the same core goal: to make kids feel safe and loved. Even if they’ll never see eye to eye, she hopes they can find ways to recognize and honor one another’s humanity — and, by doing so, help create the kind of gentle, humane world they all want for their children.

Your children’s book Pretty Perfect Kitty-Corn was challenged by a parent in a Texas school district due to fear that the unicorn it features, which has a purple mane and visible eyelashes, might cause confusion about gender and identity. What was your initial reaction to hearing that news?

Shock. I never saw that coming. Those books sprouted directly out of my friendship with my co-creator LeUyen Pham. At no point in the making of these books did Uyen and I discuss using these stories for any sort of gender or sexuality agenda. We just wanted delightful, adorable, funny, heartfelt stories about two friends who are very different on the surface but get each other deep down.

I recall that the decision to make Unicorn male was simply that we don’t usually get to see male unicorns, and boys deserve to get some unicorn representation too. And eyelashes? Both male and female horses have eyelashes (and Unicorn’s are simply a band of black delineating his eye). I never anticipated that would be an issue. But the fearful response to the book betrays a deep discomfort among many people about male characters having any characteristics deemed to be “feminine.”

I also co-create the Princess in Black chapter books, about Princess Magnolia who loves wearing pink dresses and attending parties, and she also loves putting on black boots, cape and mask and battling monsters. We published nine books with great success, and I never heard anyone complain that her booted-and-caped identity was inappropriate and harmful to kids. But book 10 features Prince Valerian, who loves wearing shiny armor and battling foes but also loves becoming the Prince in Pink by putting on a rose-colored prince suit and decorating for parties. This is the exact same situation as Princess in Black but with a male character, but the response was markedly different. I’ve been called horrible names. Recently in my home state, a group of people successfully lobbied a bookstore chain to cease carrying that book entirely. Again we see a deep fear in some about a male character showing any traits associated with femininity, even while they praise a female character showing traits associated with masculinity. This is fascinating to me, and I hope we can all notice this with curiosity and love for all involved.

I also hope people will stop calling book creators “groomers,” “pornographers,” and “pedophiles” for simply showing more than one way to be a boy. We risk diluting the meaning of those words and making real problems worse by throwing around terms injudiciously.

The local school library advisory council voted unanimously to remove the book because the unicorn accidentally sits in paint and feels ashamed about his “paint bum.” Council members said they objected to the book’s depiction of “the genital region,” especially as “a source of shame.” What do you make of their concerns?

First, I’m troubled by the council’s repeated use of the word “genitals” to refer to the buttocks. A unicorn’s rear end is not an external organ of reproduction. Again, let’s be clear on our terms.

We sought out to tell a story about deep embarrassment, and how kids can worry that their friends won’t like them anymore if they are caught doing something embarrassing. Not noticing a stain on the backside of your pants? That’s a common human experience. Bums are something all people have, so it seems very innocent to me. And kids think bums are funny, which they are! I understand they have concerns, but I hope that they will reconsider. Best practices in healthcare and child development have shown again and again that understanding bodies and having names for body parts is healthy. We don’t need to shy away from the fact that all people (and unicorns! and kitties!) have bottoms.

At the end of the book, the unicorn realizes that he doesn’t have to be embarrassed about sitting in paint. He understands that his best friend, Kitty, will accept him even if he has paint on his horn, ears, hooves, and tail, too. What did you hope this story would teach young children?

I always hope any book leaves room for kids to find whatever story or meaning they most need at that time. Looking at my own kids, I hope they know that they are lovable and worthy no matter what happens to them, what choices they make, and what other people think about them. If not met with compassion, embarrassment in anyone can turn to shame (a belief that we, deep down, are unlovable or a bad person). I take great pains and much joy imbuing my books with compassion. All people — and all characters — make mistakes. And we all deserve to be loved.

Best practices in healthcare and child development have shown again and again that understanding bodies and having names for body parts is healthy. We don’t need to shy away from the fact that all people (and unicorns! and kitties!) have bottoms.

A few of your other books were banned before Pretty Perfect Kitty-Corn. Friends Forever, a graphic novel you wrote about an eighth grader with depression who’s learning to love herself, has been banned numerous times over the years. How did you think the book might support its readers? Why do you think it became a target for bans?

Friends Forever, in fact, is about me. It’s a memoir. So it’s especially heartbreaking for me that this book has been banned. To say that my own lived experience is inappropriate for kids at my same age is very strange. 13 is the age most often left out of young people’s literature. It’s a transition age, landing between middle grade and young adult, and I feel passionately that all kids deserve to read books about themselves, whatever times and ages they are currently going through.

I think the book is honest about how it can feel to be 13 while also being kind and gentle. There is a scene (taken directly from my middle school journal) about a party I went to where a boy brought wine coolers and passed them around, and I didn’t drink any. Some adults are uncomfortable with any alcohol in children’s books. But kids today are first offered alcohol at ages younger than this. And they are more likely to say no if they’ve read a book where they got to watch a character go through that awkward experience first. Middle school is a messy, stressful, strange time. Banning books that look with compassionate honesty at this age doesn’t make the age any easier to live through, and instead it denies kids one tool that might help them survive it gracefully and make informed choices that will serve them well in the long term.

In the past, you’ve spoken up about the dangers of teaching boys that books with feminine titles and subjects, such as your Newbery Honor winner Princess Academy, aren’t meant for them. You even wrote your own picture book on the topic. Over time, have you seen gendered expectations about which readers might be drawn to certain stories evolve? How can we continue to teach kids that books are for everyone?

I still hear this sentiment all the time. “No, not that book. It’s a girl book.” In fact, I’ve heard it more than ever the past couple of years. There seems to be a renewed push from many quarters to protect boys from having to read about and learn empathy for girl characters, as if that experience might taint them somehow or change them into someone they’re not. But books don’t have the power to change who we are at our core. They can, however, help us understand and have empathy for people different from us. And reading books about people like us can help us process our own struggles and work through things that confuse and trouble us.

I recommend that adult gatekeepers don’t try to tell kids what books are for them or not for them. If recommending books to a boy, for example, maybe include at least one that’s about a female main character, without qualifying that recommendation. Just show that it’s okay to care about and read about a girl. Because it really, really is. What a gift for boys to learn to understand and empathize with half the human race.

Banning books that look with compassionate honesty at this age doesn’t make the age any easier to live through, and instead it denies kids one tool that might help them survive it gracefully and make informed choices that will serve them well in the long term.

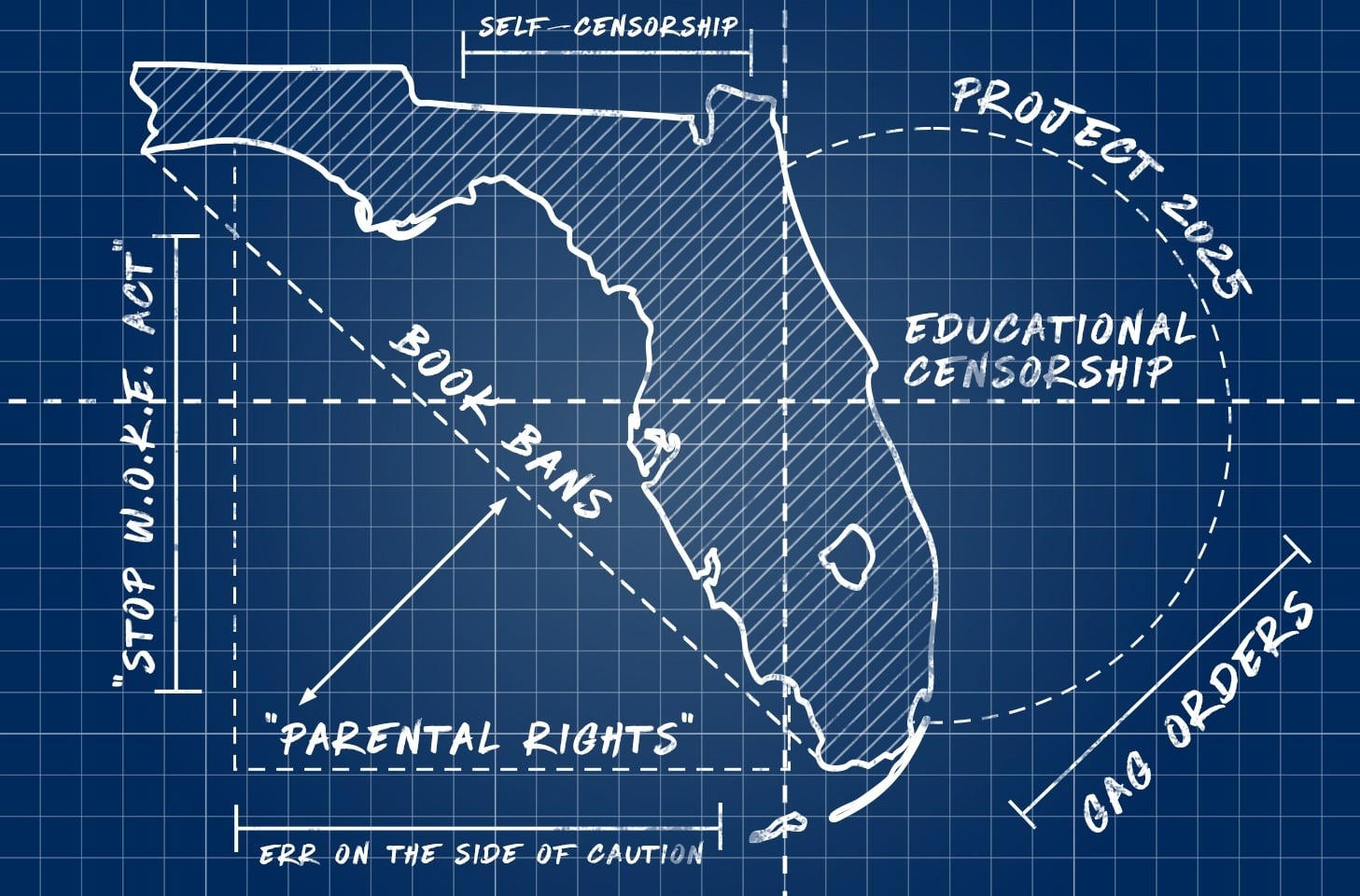

You began advocating against book bans before your own books were ever affected by them. When did you first hear about literary censorship in the U.S., and what drew you to become such a vocal proponent of the freedom to read?

I had an active blog in the 2000s, and often blog readers would ask my opinion about different books. Did I think that Bone should be banned because it showed one (adult) character smoking? Did I think Wimpy Kid inappropriate for kids because the character was self-centered and often rude? Did Harry Potter promote witchcraft and so was anti-Christian? And so on. I think I had a reputation of being a “clean” author and “safe for kids” so adults often assumed I had strict ideas about what should and shouldn’t be in books.

I loved engaging in these discussions and so appreciated the questions. My advice to parents then, as well as now, is to let your kids pick what books interest them, and then read those books too as often as you can. The discussions you have together will be invaluable, for both of you. Banning books doesn’t solve anything, especially in an age where the internet exists. Having discussions can help you both understand each other. And if you have strong moral objections to something a character does, that’s a great way to talk about it.

Teens know about sex. They know about abuse. They know a little bit about a lot of things. Reading good books and talking with adults they trust is far more enlightening and fortifying than pretending these subjects don’t exist.

How have your experiences as a parent and an author shaped your advocacy?

I was against book banning before I had kids. Authors tend to be pro-reading, so that’s not surprising. I was curious to see if my feelings would shift as a parent, especially as my kids grew older. But now with three teens and a young adult, I’m more in favor of the freedom to read than ever. I feel for my fellow parents. It’s a scary world. There’s no way to parent perfectly, no way to know exactly the right thing to do and say, and the stakes feel insurmountably high. I feel so much compassion for the parents who are understandably scared and trying to make what feels like a safe space for their kids to grow up. But from my point of view, robust libraries and the freedom to read will accomplish that goal much more profoundly than censorship. Parenting is hard, so use books as part of your team.

You’ve emphasized repeatedly that although parents should have a say in what their own kids read, they shouldn’t be able to restrict the books available to other kids. Can you tell us more about that belief?

I’m from Utah, where we can have some pretty strong feelings about the government trying to restrict the ways we parent. For example, Utah was the first state to pass a free-range parenting law, protecting parents from the crime of “child neglect” for allowing their kids to walk to school alone, for example, or to play outdoors or stay home alone, as long as the situation doesn’t pose substantial risk of harm. Why should a state legislator or school board council member who doesn’t know me or my child get to micromanage how I parent?

In this country, people are allowed their personal religious, political, and moral beliefs but can’t force others to adopt them. No one can be forced to read a book they don’t want to, and they never could. Parents have always had the option of opting their child out of an assigned school book, for example. But allowing a few people to dictate which books are available to all doesn’t make sense. I’m continually shocked that my state is the fourth worst in book banning. I sometimes hear people saying that it’s not actually book banning because people can still legally buy those books themselves. I agree with Laurie Halse Anderson that this is an elitist argument. Most children only have access to books in their school libraries. Banning books from schools and libraries has massive consequences. And it’s not only anti-Utahn, it’s anti-American.

I feel so much compassion for the parents who are understandably scared and trying to make what feels like a safe space for their kids to grow up. But from my point of view, robust libraries and the freedom to read will accomplish that goal much more profoundly than censorship. Parenting is hard, so use books as part of your team.

If you could speak directly to the organizations and individuals banning books, what would you tell them?

I would love these organizations and individuals to know that children’s book creators want the same things that they want. A safe world for kids. Protection from abuse. Peace, love and understanding. We just see things very differently. From their point of view, it may look like the banned books are threatening kids and encouraging abuse. From where I stand, the books are a soft, safe place for a kid to land, something to hold their hand, help them feel seen and better understand the world. There’s a lot of awful stuff in this world and people who want to hurt kids. Children’s book creators like us are trying to help the best ways we can. We see books not as part of the problem but a huge part of the solution.

These organizations and individuals are absolutely free to disagree with my opinions and keep their own, but I hope they understand that we’re coming from a good place. I hope that the violent, divisive, fearful rhetoric can tone down, and that they can remember we’re human beings with beating hearts and families we love, and we are doing our best. And I know that they are also human beings with beating hearts and families they love, and they are doing their best too. We can disagree, but if at the same time we can honor each others’ humanity, the world instantly becomes a more loving and kind place for all our kids.

Use books and discussions about books with your kids as one of the best tools in your parenting toolbelt. And please, be kind to yourselves! We all sit in paint sometimes. And we all still deserved to be loved.