Scholar-Author Imani Perry on Listening Deeply, Turning 50, Writing About Historical Atrocities and Being a Mother

Prize-Winning Author of South to America is Featured Speaker in Finale of Birmingham Reads, PEN Birmingham’s Collective Reading Experience of Her Book

By Suzanne Trimel

(BIRMINGHAM, AL)— Imani Perry, the prize-winning author and scholar, returned to her birthplace on Wednesday evening for a conversation at the historically-black Miles College that was both the finale of PEN America’s citywide Birmingham Reads project and a homecoming to the city where she has said her heart lies.

Perry, who teaches African American studies at Princeton, mentioned as she began her talk that her mother taught at the 125-year-old Miles College when she was pregnant with her. “So it feels like a place that is one of the sites of my own beginning.”

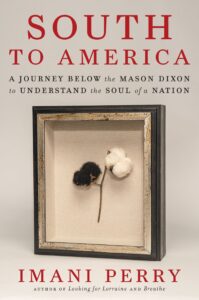

PEN America’s Birmingham Reads project encouraged the city to read together Perry’s National Book Award-winning title South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation. It is a highlight of the PEN Across America program, which brings the PEN mission to 10 chapters across the country.

Students, faculty, and readers who joined PEN America’s collective reading heard Perry’s thoughts— on the first day of Black History Month —on wide-ranging subjects: the moment that unexpectedly changed her life (winning the PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award in 2019); why listening deeply to others and especially elders is key to a writer’s success; why she still grapples with the meaning of turning 50; why the tradition of “black folks holding onto things” has had a big impact on scholarship, and more.

She said she debated going to the 2019 PEN America Lit Awards ceremony in Manhattan because she could not imagine she’d win. “When they called my name, I was stunned. That moment changed my life,” she said of her first book prize. South to America has been longlisted for this year’s PEN/John Kenneth Galbraith Award for Nonfiction. The winner will be announced March 2.

She said she debated going to the 2019 PEN America Lit Awards ceremony in Manhattan because she could not imagine she’d win. “When they called my name, I was stunned. That moment changed my life,” she said of her first book prize. South to America has been longlisted for this year’s PEN/John Kenneth Galbraith Award for Nonfiction. The winner will be announced March 2.

The conversation was intimate, much like a family member or friend sharing confidences, affectionate advice and sympathetic insights.

Ashley Jones, the Alabama poet-laureate and co-director of the PEN-Birmingham chapter, introduced the event, noting that the chapter—along with PEN Across America’s nine others—mobilize people to defend free expression and free speech on their home ground while also celebrating local literary achievement and creative expression. PEN America’s national reach to fight against attacks on free expression has been ignited over the last year and a half in the face of escalating censorship nationwide from book bans and educational gag orders. PEN America has been at the forefront of documenting both.

Perry’s book, chosen last August by the chapter, was a natural fit for the series, which drew more than 100 readers to probe the mix of themes she writes about: hip hop, race, racism, and slavery; atrocities and resistence; the South’s relationship to “Americanness” and her own beloved grandmother.

Inspired by Albert Murray’s 1971 memoir-travelogue “South to a Very Old Place,” Perry visited over a dozen Southern cities and towns, looking at history and today’s realities.

On stage at the college’s historic Brown Hall, Birmingham-based teaching artists Tania De’Shawn and Brianna Jordynn Wright served as Perry’s interlocutors, drawing questions from the author’s experiences in the classroom, as writer, as a mother and daughter, and a noted scholar of African American history, literature, culture and thought. Afterward, the audience had their turn at questions.

A sampling follows:

How does South to America relate to the 1619 Project?

“I think of them as kindred spirits. The 1619 Project is an intervention into telling the history in a more rigorous and truthful way, than the official story that marginalizes and erases black life from that story and also eliminates the harm [that resulted].”

Is telling the history of the South a burden?

“For me, it’s a responsibility but not a burden. It brings us to an understanding of how do you live a life of meaning and purpose? How do you bear witness to the truth as you see it.”

What makes you feel most respected?

“Listening deeply. To me, writing is an invitation to listen. And it creates a ‘sympathetic vibration,’ as in music when you are playing and someone facing you is playing and makes the strings on the other instrument tremble. Listening has that same possibility. You have to be open to hearing that. We often don’t listen, particularly to people who are deemed not important in our society.”

Nothing is exactly how it appears in the South: What does our culture’s duality reveal about us?

“In the [current] battles over what we are going to teach, the reality is the story itself is the conflict. Who matters and who doesn’t? These are issues that have been struggled over for hundreds of years. That’s what the duality teaches us.”

What role do you think HBCUs play in preserving Black history and artifacts?

“A huge role,” Perry said, noting her own research with a Harvard colleague to digitize the historic journals of Black teachers, which offer new insights into the history of Black education. “Institutions and professional organizations have held onto papers that other people didn’t think were important and it turns out they can be instrumental to historians and researchers.”

She also talked about the artifacts of Black history and culture that are in private hands that have been valuable to scholars; for example, the historian David Blight gave a talk in Savannah, GA, about Frederick Douglass where he met a surgeon and collector who stunned him by showing him Douglass’ family scrapbooks that were part of his collection. The scrapbooks became a seedbed for Blight’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2018 biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.

“The tradition of black folks holding onto things because they knew they were important means a lot to history and scholarship,” Perry said.

What does she hope readers will take away from South to America?

“I hope that it opens more conversations and contemplations,” noting that a student of hers of Chinese background relayed that her grandparents lived for years in Georgia but never talked about their lives there. The student read South to America and began to open conversations with her grandparents about the South.

How did Zora Neale Hurston influence her?

“There are so many books about traveling through the South. Almost none are by women, and fewer are by Black women because of the real worry about safety. Zora showed immense courage in moving through the South and also the Caribbean and seeing the connections between the two. She figured out how to talk to people. She went as an anthropologist. She really transformed anthropology, how you talk to people in a way that is effective. The way she placed value on recording folk songs is as important as her intellectual work. My first book was on hip hop and I also feel able to move between being a scholar and being a creative writer.”

From a student who wants to be a writer: How can you write about home?

“Keep it small. One of the best writing lessons is to remember that stories are intimate. Keep [the focus] small and specific because you can be overwhelmed if you think about everything. Be attentive– a kind of love. Locate your attention in a loving gaze.”

Watch a recording of the event here: https://www.facebook.com/MilesCollege/videos/6031756243574966