Ukrainian Culture Under Attack

Erasure of Ukrainian Culture in Russia’s War Against Ukraine

On War and Cultural Erasure, by PEN America President Ayad Akhtar >>

WATCH: PEN America’s video coverage of Ukrainian Culture Under Attack >>

PEN America Experts:

Managing Director, PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center

Summary

On October 10, Victoria Amelina, a prize winning author, sent out a series of urgent tweets. “I’m in Kyiv and alive,” she started off, explaining that she was filming Russian strikes on Kyiv as best as she could. She tweeted out a list of the buildings damaged or destroyed during the attack, including the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, the Khanenko Museum, Kyiv Picture Gallery, National Philharmonic of Ukraine, Maksymovych Scientific Library, and Kyiv City Teacher’s House. Her anguish at these losses and her understanding of why they had been targeted was crystal clear: “I know they want us, Ukrainian writers, to disappear . . . they target Ukrainian culture.”

Culture—past, present, and future—is on the front lines of the brutal war on Ukraine and cultural erasure is a central tactic of Russia’s campaign of aggression and violence in Ukraine, which has gone on for over eight years. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s repeated false claims that a distinct Ukrainian history, language, and culture do not exist, serve as one of his central justifications for waging war on and occupying Ukraine. He seeks not only to control Ukrainian territory, but to erase Ukrainian culture and identity, and to impose Russian language, as well as a manipulated, chauvinistic, militaristic version of Russia’s culture, history, and worldview, on Ukrainian people.

Our culture and our physical survival are intertwined—they go hand in hand.

Oleksandra Yakubenko, Artists at Risk Connection’s (ARC) Ukraine Protection Program

Oleksandra Yakubenko, currently working on PEN America’s efforts to support Ukrainian artists at risk and an expert on Ukrainian culture, thinks that Putin’s efforts to destroy Ukrainian culture have had the opposite effect. She explained how her Ukrainian identity was “reawakened” in 2014 in the aftermath of the Maidan Revolution that ousted President Viktor Yanukovych—what Ukrainians call the Revolution of Dignity—and following Russia’s occupation of Crimea and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Since then, she noticed “cultural life just bloomed and bloomed.” She ascribed this strengthening, in part, to the vitality of Ukraine’s cultural sector and their participation in and support for democracy and human rights, and later the war effort. She now believes that “our culture and our physical survival are intertwined—they go hand in hand.”1Oleksandra Yakubenko, telephonic interview with staff of PEN America, October 31, 2022

In an interview from July 2022, the Ukrainian novelist, poet, and essayist Yuri Andrukhovych shared similar views on Ukrainian culture and writing as a bulwark against Russian aggression: “It’s quite ironic that each attempt Russia has made to destroy Ukrainian culture has had the opposite effect . . . There is now a widespread tendency among Ukrainians to speak entirely in Ukrainian . . . New poems, novels, stories, essays, etc. will be written in Ukrainian, and of course they will be read and discussed. It is the best way to overcome the Russian aggressors and to survive in that humanitarian catastrophe they have brought upon us.”2Kate Tsurkan, “Writers Are the Middlemen Between the Human Race and Immortality”: A Conversation with Yuri Andrukhovych,” Los Angeles Review of Books, July 26, 2022, lareviewofbooks.org/article/writers-are-the-middlemen-between-the-human-race-and-immortality-a-conversation-with-yuri-andrukhovych/

Russia has carried out extensive, coordinated actions to marginalize, undermine, and ultimately eliminate the tangible and intangible manifestations of Ukrainian culture since its illegal occupation of Crimea, and parts of Luhansk and Donetsk.3In February 2014, unlawful, so-called self-defense units, aided by Russian security forces, seized administrative buildings and military bases across Crimea and installed a pro-Russian leadership. Also in 2014, Russia-backed armed insurgents seized control of many cities and towns in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Ukrainian government forces had been fighting against the separatists for control since 2014. See: “Conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas: A Visual Explainer,” International Crisis Group, accessed September 25, 2022, crisisgroup.org/content/conflict-ukraines-donbas-visual-explainer Russia’s actions, which included damaging important cultural buildings and undermining the teaching of and in Ukrainian in those territories, now serve as a blueprint for their cultural erasure efforts in areas they have invaded and occupied since the full-scale war against Ukraine began on February 24, 2022. They have been supplemented by physical destruction of cultural infrastructure on a massive scale.

This is not the first time that the Russian government has sought to destroy Ukrainian culture. Ukrainian thinkers, writers, linguists, artists, and scholars over the last three centuries have faced Imperial Russian and Soviet efforts to deny, assimilate, and eliminate their culture and language. Olesya Khromeychuk, a historian and director of the Ukrainian Institute in London, detailed efforts by various Russian tsars to eliminate Ukrainian culture, including banning Ukrainian-language publications, prohibiting cultural societies, and exiling or imprisoning public intellectuals. She explained that “writers, poets, and artists became the figures who shaped national identity.”4Olesya Khromeychuk, “Putin Says Ukraine Doesn’t Exist. That’s Why He’s Trying to Destroy It,” The New York Times, November 1, 2022, nytimes.com/2022/11/01/opinion/ukraine-war-national-identity.html

Deliberate attacks on culture, including efforts to erase culture, by state and non-state actors, are not new.5UN Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights, “Report on the intentional destruction of cultural heritage as a violation of human rights” A/71/317, August 9, 2016, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/thematic-reports/a71317-report-intentional-destruction-cultural-heritage-violation-human The bombing of Guernica, a Basque town in northern Spain, by the German air force in support of General Franco during the Spanish Civil War; the systematic destruction of Polish libraries and archives by the Nazis during World War II; attacks on cultural heritage sites, including Palmyra in Syria, by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) are among the better-known efforts to destroy and erase culture during wars. In 2016, the International Criminal Court (ICC) handed down its first conviction of a war crime “consisting in intentionally directing attacks against religious and historic buildings in Timbuktu, Mali.”6“ICC Trial Chamber VIII declares Mr. Al Mahdi guilty” International Criminal Court, September 27, 2016, icc-cpi.int/news/icc-trial-chamber-viii-declares-mr-al-mahdi-guilty-war-crime-attacking-historic-and-religious

The occupation and war have wrought an incalculable toll on Ukraine’s cultural voices, creators, and workers. They are amongst the thousands killed and injured by Russian attacks, or detained and threatened by Russian forces. Many have fled their homes and communities to reach safety; they have lost loved ones, homes, and precious possessions. They have been cut off from their creative communities and colleagues, and they have seen their studios, galleries, and exhibition spaces destroyed, damaged, and closed. The need to focus on survival has frequently taken precedence over creative work and even when Ukrainian culture is not being deliberately targeted, the war has deeply disrupted creative production.

Russian bombardments and other attacks have destroyed and damaged hundreds of places where Ukrainians enjoy and experience culture, sites small and large, local and national, from community cultural houses to fine art museums. Some of these attacks were deliberate, targeted attacks, such as on Mariupol’s Academic Regional Drama Theater, which was sheltering hundreds of civilians, including children, when Russian aircraft dropped two bombs on it in March 2022. In the Kyiv region, in the first days of the Russian assault, a Russian missile struck the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum, setting it on fire, the only building in the village to be struck during that time.

Russian forces have also repeatedly and indiscriminately attacked densely populated areas using explosive weapons and cluster bombs, which have been banned by an international treaty. These attacks have caused widespread death and injury, as well as massive destruction and damage to civilian infrastructure, including cultural heritage sites, book printing houses, libraries, and places of spiritual interest. The damage and destruction cannot be seen as simply incidental, collateral damage resulting from Russian military operations targeting Ukrainian military targets. Rather, the magnitude of the destruction suggests a deliberate campaign to destroy civilian infrastructure, rendering some cities barely habitable, and an attempt to destroy civilian morale.

Both the targeted and indiscriminate attacks carried out by the Russian military against civilian infrastructure in Ukraine are violations of International humanitarian law (IHL) and, per the findings of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine, actions by Russian forces amount to war crimes.7“Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine (Advance Unedited Version),” A/HRC/49/71, October 18, 2022, ohchr.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/A-77-533-AUV-EN.pdf The conduct of Russia’s military and occupation forces also violates international human rights law, including Ukrainians’ right to culture.

Russia has carried out extensive, coordinated actions to marginalize, undermine, and ultimately eliminate the tangible and intangible manifestations of Ukrainian culture since its illegal occupation of Crimea, and parts of Luhansk and Donetsk.

Ukrainian writers, poets, artists, and cultural defenders demonstrate remarkable resilience and resistance in the face of this brutal conflict and attack against their Ukrainian culture. Many draw strength from their connections to Ukrainian culture and are actively seeking new ways to produce and promote culture. Writers are writing wartime diaries. There are literary readings in bookstores against the backdrop of air-raid sirens, and concerts in metro stations doubling as bomb shelters. “Good Evening (Where Are You From?),” also known by its popular name, “Good evening, we are from Ukraine,” is a song by the electronic duo ProBass and Hardi. It was released just before the start of the war, and it now plays in bomb shelters; the phrase is printed on T-shirts and trends on Twitter, and is often used by officials, including Vitaliy Kim, the governor of the southern region of Mykolaiv, when they address the Ukrainian people, signifying and strengthening Ukrainian resilience. Many believe that the survival of Ukraine as a country and people is inextricably linked with the survival of its culture, and they carry that burden with them. Tamara Shevchuk, a painter, graphic designer, and art teacher, works in a village in the Kyiv region that was occupied by the Russians for 24 days. She said: “War does not spare anyone, and the cultural front is just as important as the military one.”8Tamara Shevchuk, interview on file with PEN America

The Ukrainian government and civil society are working to protect and preserve Ukrainian culture, with the support of the international community, which has responded to Russia’s war with economic, political, financial, and military support for Ukraine, including notable efforts to protect cultural heritage and support cultural workers. However, traditional approaches to cultural preservation in wartime have focused mostly on tangible, physical manifestations of culture—protecting works of art or artifacts and prominent buildings. The 1954 Hague Convention includes a narrow definition of culture entitled to protection, namely movable or immovable property, and that which is specifically “of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people.”

War does not spare anyone, and the cultural front is just as important as the military one.

Tamara Shevchuk, painter, graphic designer, and art teacher

However, culture comprises significantly more than just the buildings we can visit and the objects we can admire. The concept of “heritage” is also a limiting one, in that it denotes a cultural past without reference to the present or future. Culture comprises peoples’ beliefs, customs, mythology, knowledge, traditions, and perspectives on the past, present, and future, as manifested in its art, literature, music, dance, religion, and other forms. Culture unites and gives words and expressions to shared feelings and experiences. As this report demonstrates, these crucial aspects of Ukraine’s culture are under direct attack and facing serious threats.

Ukraine’s international partners and anyone supporting Ukrainian efforts to survive as an independent, democratic nation must move beyond a narrow definition of cultural heritage, and instead take an expansive and people-centered view to ensure Ukrainian culture can flourish for generations to come. This means paying greater attention to the survival and well-being of those who create, inspire, and develop culture in all of its varied forms. Equally important are those who curate, care for, and preserve Ukrainian culture: museum workers, curators, archivists, librarians, and others.

As the Ukrainian government, its international allies, and multilateral institutions plan for the future phases of this war and its aftermath, cultural vitality and continuity should be an explicit point of emphasis, aiming to ensure that Russia’s war on Ukrainian culture does not succeed.

Destroying our culture is the purpose of everything the Russians are doing. Culture and language strengthen our nation, they remind us of our history. That’s why the Russians are shelling our monuments, our museums, and our history. That’s what they’re fighting with. They want to destroy everything and substitute our history.

Marjana Varchuk, director of communications at The Khanenko Museum

A War of Cultural Erasure

President Putin, senior Russian officials, government think tanks, and pro-government public intellectuals have repeatedly denied that Ukraine exists as a nation or that Ukrainians have an identity and culture distinct from that of Russia and Russians. This claim has been used to justify the war and occupation and negate Ukraine’s claim to sovereign nationhood. This rhetoric dates back to Russian Imperial and Soviet times. During Soviet rule Ukrainians were subjected to a deliberate attempt to destroy them as a nation that included efforts to suppress their language.

Marjana Varchuk, the director of communications at The Khanenko Museum in Kyiv, which was partially damaged in an airstrike on October 10, 2022, agreed. She said: “Destroying our culture is the purpose of everything the Russians are doing. Culture and language strengthen our nation, they remind us of our history. That’s why the Russians are shelling our monuments, our museums, and our history. That’s what they’re fighting with. They want to destroy everything and substitute our history. In fact, the main problem is our common post-Soviet period heritage, when the Ukrainian language was banned for 70 years. At least 400 years before that, the Ukrainian language, literature, theater, everything associated with our history, was banned and destroyed by the Russians who substituted the truth with a lie.”9Marjana Varchuk, in person interview with consultant of PEN America, October 11, 2022

In the current context, Russian denialism re-emerged prominently 14 years ago, in relation to potential NATO membership for Ukraine, which the Russian government has always vehemently opposed. During a 2008 NATO Summit, Putin said, “Ukraine is not even a state! What is Ukraine? Part of its territory is Eastern Europe, and part, and a significant one, was donated by us.”10“Блок НАТО разошелся на блокпакеты [The NATO Bloc broke up into bloc packages],” Kommersant, April 7, 2008, hkommersant.ru/doc/877224. For one compilation of relevant statements see: Clara Apt, “Russia’s Eliminationist Rhetoric against Ukraine: A Collection,” updated August 1, 2022, justsecurity.org/81789/russias-eliminationist-rhetoric-against-ukraine-a-collection/

After Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014, Putin justified the action by claiming Crimea is “an inseparable part of Russia” that reflects Russia and the region’s “shared history and pride.”11Vladimir Putin, “Address by President of the Russian Federation,” Kremlin Website, March 18, 2014, en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20603 At the same time, the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (RISS), a think tank under the Russian presidential administration, published a collection of essays titled Ukraine is Russia, which was “dedicated to the concept of unity of the Russian world” and describes “Ukrainian-ness” as “a peculiar South Russian” regional concept.12“An Independent Legal Analysis of the Russian Federation’s Breaches of the Genocide Convention in Ukraine and the Duty to Protect,” New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy and Raoul Wallenberg Center for Human Rights, May 2022, newlinesinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/English-Report.pdf

In a July 2021 essay published on the Kremlin website, Putin claimed that there is no historic basis for the “idea of Ukrainian people as a nation separate from the Russians,” that Russians and Ukrainians are “one people,” and that no Ukrainian nation existed prior to Soviet Russia’s creation of it. In Putin’s view, everything and everyone identified as Ukrainian is effectively fiction, which must be eliminated, and Ukraine must be returned to the so-called “Russian World.”13Vladimir Putin, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” Kremlin website, July 12, 2021, en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181 See also analysis by Maria Domańska, “Putin’s article: ‘On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians,’” Center for Eastern Studies, July 13, 2021, osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2021-07-13/putins-article-historical-unity-russians-and-ukrainians

To further delegitimize Ukrainian national identity and culture and justify the invasion, Russia resorted to the demonization of Ukrainian culture by evoking Nazism. Putin and the pro-Putin ideological elite have described Ukrainian political leadership and Ukrainian people as “Nazis,” with Russia originally describing its military goal to “denazify the country.”14Timofei Sergeitsev, “Что Россия должна сделать с Украиной?” [What Should Russia Do with Ukraine?], RIA Novosti, April 3, 2022, ria.ru/20220403/ukraina-1781469605.html “Address by the President of the Russian Federation,” Kremlin website, February 24, 2022, en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67843 See also the analysis by historian Timothy Snyder, “Russia’s Genocide Handbook,” April 8, 2022, snyder.substack.com/p/russias-genocide-handbook In this grotesquely contorted framing, Ukrainian culture develops and nourishes “Nazism” by a so-called “systemic glorification of Nazism” through rituals, literature, history, culture, and media.15Full text:“Осуществляется системная героизация нацизма и практикуется антисемитизм — и не только в форме ритуалов (например, известных гитлеровских факельных шествий с нацистской символикой), но и в качестве включения биографий нацистских преступников времен войны и их версии исторических событий в обязательные общеобразовательные программы, культурную политику, контент СМИ.” Timofei Sergeitsev, “Какая Украина нам не нужна(The Kind of Ukraine We Do Not Need),” Ria Novosti, April 10, 2022, ria.ru/20210410/ukraina-1727604795.html See also “Именно через культуру и образование была подготовлена и осуществлена глубокая массовая нацификация населения.” “The deep, massive Nazification of the population was carried out specifically through culture and education…” Timofei Sergeitsev, “Что Россия должна сделать с Украиной? (What Should Russia Do with Ukraine?).”

Russia has made clear that the elimination of culture is an explicit target of its campaign in Ukraine and has used this specious charge of “Nazism” as justification: “Denazification of the mass of the population consists in re-education, which is achieved by ideological repression (suppression) of Nazi attitudes and strict censorship: not only in the political sphere, but also necessarily in the sphere of culture and education.”16Ibid. This will include “the withdrawal of Ukrainian educational materials, the establishment of pro-Russian memorials, commemorative signs, monuments, and imposition of a Russian information space. Ukrainians should be punished for understanding that they exist as a separate people and for participating in Ukrainian cultural life, including by death, imprisonment, or sentences in labor camps.”17Ibid.

Russia’s leadership has further sought to justify its actions in Ukraine with false claims of widespread and pervasive attacks and discrimination against Ukraine’s Russian speakers, a population that Russia regards as ethnically Russian (of note, Putin’s claim that Ukrainian Russian speakers possess an ethnic identity distinct from their neighbors contradicts his assertion that all Ukrainians are ethnically indistinguishable from Russians). Putin has falsely alleged that the Ukrainian government sought to “root out the Russian language and culture” and that “people who identify as Russians and want to preserve their identity, language, and culture are getting the signal that they are not wanted in Ukraine.”18Vladimir Putin, “Address by the President of the Russian Federation,” Kremlin website, February 21, 2022 en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67828

The Russian occupation has completely transformed political, civic, educational, and cultural life in Crimea.

Cultural Destruction and Erasure Between 2014 and 2022

Attacks on Culture in Crimea

Russia’s assault on Ukrainian territory did not begin in February 2022, but eight years earlier, with the illegal occupation of Crimea in February 2014. Its campaign against Ukraine’s culture began then as well. Russia occupied Crimea after the Revolution of Dignity, also known as the Maidan Revolution, which led to the ousting of the Russian-backed Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych. These protests, which were part of the Euromaidan starting in November 2013, were catalyzed by President Yanukovych’s decision not to enter into a free trade agreement with the European Union.

Russia now administers Crimea as a region of the Russian Federation, based ostensibly on a sham referendum held by local authorities that took place without the authorization of the Ukrainian government and that went unrecognized by the international community.19“Rights in Retreat: Abuses in Crimea,” Human Rights Watch, November 17, 2014, hrw.org/report/2014/11/17/rights-retreat/abuses-crimea It has installed Russian governance structures and the Russian ruble as the official currency. Crimea’s residents were forced to accept Russian passports and residents were conscripted into the Russian armed forces. The Russian occupation has completely transformed political, civic, educational, and cultural life in Crimea.

The Russian authorities have taken various steps to eradicate Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar culture since 2014. They have harassed and threatened people who produce and protect culture, tried to quash the use of Ukrainian and Tatar languages in schools and in the media, and damaged important cultural heritage sites.

Russian authorities have repeatedly harassed and threatened people associated with the Ukrainian Cultural Center, an NGO established in Simferopol in May 2015 to support Ukrainian culture, history, and language. The Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) and prosecutors interrogated staff members, searched their homes, and, in some cases, confiscated their computers and books.20Halya Coynash, “Russian FSB terrorizes another Ukrainian activist in occupied Crimea,” Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, February 12, 2019, khpg.org/en/1549897598 “Persecution of Ukrainian Cultural Center activist in Crimea,” The Crimean Human Rights Group, August 29, 2018, https://crimeahrg.org/en/persecution-of-ukrainian-cultural-center-activist-in-crimea/ Many of those associated with the center have fled Crimea for their safety.21Coynash, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group.

Russia has further harassed, threatened, arrested, disappeared, and prosecuted writers, journalists, and others who voiced their opposition to its occupation. As of June 2022, Russia had imprisoned 162 Ukrainian journalists, activists, writers, and others on politically motivated charges and detained them in Crimea or illegally transferred them to the Russian Federation, according to the Mission of the President of Ukraine in Crimea.22Mission of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, “Freedom of Expression,” on file with PEN America. The majority, 103 people, are Crimean Tatar.23Ibid.

Vladyslav Yesypenko, a journalist and recipient of the 2022 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award is among the imprisoned.24“2022 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award Honoree Vladyslav Yesypenko,” PEN America, accessed August 15, 2022, pen.org/2022-pen-barbey-freedom-to-write-award-honoree-vladyslav-yesypenko/ The FSB detained Yesypenko in March 2021 immediately after attending an event in honor of Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko in Simferopol. He was tortured in detention and, in February 2022, sentenced to six years in prison.25”2022 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award Honoree,” PEN America.

Yesypenko’s arrest after participating in a Shevchenko memorial event links to a long history of resistance associated with the national poet. In the 1960s, Ukrainians peacefully demonstrated against the Soviet regime by gathering at monuments to Shevchenko on March 9 and 10 to commemorate his life.26Shevchekno was born on March 9, 1814 and died on March 10, 1861. See: Yaro Bihun, “Washingtonians Honor Shevchenko with a Gathering at His Monument,” The Ukrainian Weekly, March 13, 2020, ukrweekly.com/uwwp/washingtonians-honor-shevchenko-with-a-gathering-at-his-monument/ They would read poems, sing Ukrainian songs, and lay flowers. These gatherings required courage as they could, and frequently did, lead to persecution.

In this spirit, residents of Crimea gathered near monuments to Shevchenko to mark the 200th anniversary of his life on March 9, 2014, and to protest the Russian occupation. Small protests have continued annually, although the Russian authorities prohibited the gatherings and prosecuted participants, including for flying the Ukrainian flag or singing the national anthem.27See, for example, Halya Coynash, “Ukrainian anthem prohibited as ‘provocation’ on Shevchenko anniversary in Russian-occupied Crimea,” Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, March 10, 2020, khpg.org/en/1583795393. And Halya Coynash, “Honouring Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko banned in Russian-occupied Crimea,” Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, March 3, 2016, khpg.org/en/1456950004 Occupying authorities eventually started organizing their own “official” events near the monuments in order to elevate Russian culture and preempt the Crimean cultural gatherings. They displayed Russian flags, gave speeches, and described Shevchenko as “a Russian writer” and “a unifying image of the three Slavic peoples.”28“Under the tricolor and with “self-defense.” In Simferopol, the memory of the Ukrainian Kobzar was honored (+ photo), KrymRealii, March 19, 2019, https://ru.krymr.com/a/news-v-v-simferopole-pochtili-pamyat-ukrainskogo-kobzarya/29812137.html

Russian authorities have also attempted to suppress the use of Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian languages in schools. Officials have pressured children and their parents not to request Crimean Tatar- or Ukrainian-language instruction,29Halya Coynash, “Russia uses threats and intimidation to drive Crimean Tatar language out of schools in occupied Crimea,” Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group,” May 21, 2019, khpg.org/en/1558108888 and instruction in these languages, especially Ukrainian, has decreased.30“No Ukrainian-language media school has remained in Crimea,” The Crimean Human Rights Group, March 14, 2019 crimeahrg.org/en/no-ukrainian-language-media-school-has-remained-in-crimea/ In 2017, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) expressed concerns about “restrictions faced by Crimean Tatars and ethnic Ukrainians in exercising their economic, social, and cultural rights, particularly the rights to work, to express their own identity and culture, and to education in the Ukrainian language.”31UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, “Concluding Observations on the sixth periodic report of the Russian Federation,” E/C.12/RUS/CO/6, October 16, 2017, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/concluding-observations/committee-economic-social-and-cultural-rights-concluding-5

Russian authorities have banned access to independent media and Ukrainian- and Crimean Tatar-language broadcasts, replacing the content with Russian programming and a pro-Russian Crimean Tatar-language station.32“Pro-Russian Crimean Tatar TV Channel Starts Satellite Broadcasting,” RFE/RL, April 1, 2016, ferl.org/a/crimea-pro-russian-tatar-tv-station/27648579.html The Crimean Human Rights Group has reported numerous efforts to block popular Ukrainian online media. In April 2021, they reported that 22 Ukrainian websites were completely unavailable in Crimea.33“At Least 12 Crimean Providers Blocking Ukrainian Websites in Crimea,” The Crimean Human Rights Group, April 4, 2021, crimeahrg.org/en/at-least-12-crimean-providers-blocking-ukrainian-websites-in-crimea/ They have also documented various efforts to jam Ukrainian FM radio station signals, again limiting access to Ukrainian media in Crimea.34“Jamming of Ukrainian FM Radio Station Signal in North of Crimea Amplified Again,” September 30, 2021, crimeahrg.org/en/jamming-of-ukrainian-fm-radio-station-signal-in-north-of-crimea-amplified-again/

Russian occupation authorities are also undertaking large-scale construction at the ancient archaeological complex of Tauric Chersonese located near Sevastopol, a landmark which Putin ordered to be put under direct Russian control in 2015. The site is a city founded by Greeks in the fifth century B.C., which stood until the 15th century, and contains ruins and artifacts from the Greek, Roman, and Byzantine periods.35“Ancient City of Tauric Chersonese and its Chora,” UNESCO, accessed September 25, 2022, whc.unesco.org/en/list/1411/ It is included in the UNESCO World Heritage List.36“Ancient City of Tauric Chersonese and its Chora,” UNESCO. Russian authorities have conducted illegal excavations, added buildings and infrastructure directly on top of some ruins, and developed entertainment venues at the site to attract visitors, in an effort to create “one of the largest [Russian] federal cultural centers,” according to one of the officials involved in the development.37“Chersonese: “Orthodox Mecca” with opera and ballet on ancient ruins,” Krym Realii, July 29, 2020, ru.krymr.com/a/hersones-pravoslavnaya-mekka-s-operoj-i-baletom-na-drevnih-ruinah/30755245.html Putin has referenced the site as part of messaging aimed to falsely suggest deep historical ties between Russian and Crimea, describing the site as a “”Russian Mecca” from which a unitary Russian national state, and, in fact, the Russian nation emerged.”38“…было создано “единое национальное Русское государство и, по сути, русская нация.” “Putin Proposes to Create a Russian Mecca in Chersonese,”Interfax, August 18, 2017, https://www.interfax.ru/russia/575482; “Irretrievable losses of ancient Chersonese,” Krym Realii, October 8, 2019, https://ru.krymr.com/a/bezvozvratnye-poteri-drevnego-hersonesa/30204032.html (all accessed September 25, 2022). Putin’s claim is linked to the baptism of Kyivian prince Volodymyr the Great in Chersonese in 988, bringing Christianity to the Slavic people in Kyivan Rus, which is distinct from the development of Christianity in Muscovy, the predecessor to the Russian empire.

Specific Efforts to Eradicate Crimean Tatar Culture

Russian efforts to eradicate culture in Crimea have included systematically eliminating the identity, language, and culture of the Crimean Tatar community.39See for example, the extensive human rights monitoring of the situation in Crimea by Crimea SOS, including Persecutions in Crimea in the Context of a Full-Scale Russian Invasion of Ukraine, June 16, 2022, krymsos.com/en/represiyi-v-krymu-v-umovah-povnomasshtabnoyi-vijny-rosiyi-proty-ukrayiny/; ongoing documentation by the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, khpg.org/en/page_1; as well as, for example, “Ukraine: Fear and Repression in Crimea,” Human Rights Watch, March 18, 2016, =hrw.org/news/2016/03/18/ukraine-fear-repression-crimea and other Human Rights Watch reports. The Crimean Tatars are indigenous Muslims who have suffered a long history of repression, violence, and persecution, including mass deportation from Crimea by the USSR after World War II. Alim Aliyev is a Ukrainian-Crimean Tatar human rights defender, journalist, deputy general director of the Ukrainian Institute, and board member of PEN Ukraine. He provided a stark description of Russian efforts to destroy Ukrainian and Tatar culture: “Attempts are being made to turn the people of Crimea into speechless citizens of Russia by changing their identity. Languages have been banned and cultural heritage destroyed.”40Alim Aliyev, “Halting the Wheel of History,” Eurozine, July 4, 2022, eurozine.com/halting-the-wheel-of-history/

Shortly after the occupation began, the authorities also banned41See Alexander Winning, “Crimean Tatars commemorate Soviet deportation despite ban”, Reuters, Reuters, may 18, 2014,https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-ukraine-crisis-crimea-tatars/crimean-tatars-commemorate-soviet-deportation-despite-ban-idUKKBN0DY0H320140518 the large public gatherings traditionally held by Crimean Tatars every year to remember and mark the anniversary of the Sürgün, or Stalin’s mass deportation of the Crimean Tatar people in May 1944.42Yegveny Matyushenko, “Genocide of Crimean Tatar people: Ukraine honors memory of victims,” May 18, 2021, unian.info/society/genocide-of-crimean-tatar-people-ukraine-honors-memory-of-victims-11423263.html

Russian occupying forces have systematically attacked Crimea’s cultural heritage, taking over 4,095 sites of national and local importance and including them in Russia’s cultural heritage protection system. In some cases, this has resulted in significant harm to protected cultural sites.43Mission of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, “Informational and analytical note on the situation with cultural and archaeological heritage in the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol,” on file with PEN America. The occupying authorities have also unlawfully transferred artworks and artifacts from Crimea for exhibitions in numerous cities in Russia, and undertaken unauthorized archaeological excavations or mounted construction initiatives on archaeological and cultural heritage sites, including some dating to medieval and ancient times.44“Cultural Heritage of Crimea,” Crimean Institute of Strategic Studies, “culture.crimea.ua/ua/home.html (accessed September 25, 2022). These activities may infringe on the article 9 of Second Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention, which prohibits such activity except where it is necessary to “safeguard, record or preserve cultural property.”

Among the architectural monuments on which Russian authorities have undertaken concerning construction work is the famous 16th-century Khan’s Palace, or Hansaray, a significant emblem of Crimean Tatar culture. Experts have criticized the construction as threatening the monument’s conservation. What Russian officials claim is “restoration” work to preserve the palace, instead, has involved the removal of original oak ceiling beams and handmade roofing tiles, and damage to wall frescoes.45Halya Coynash, “Renowned Crimean Tatar civic activist jailed after exposing Russia’s destruction of 16th century Khan’s Palace,” Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, February 18, 2022, khpg.org/en/1608810100 Experts claim the contractors hired to do the work do not have restoration experience, and there is no evidence that necessary expert assessments were conducted.46“Elena Removskaya, ’Vandalism masquerades as restoration.’ New contractors from Russia in the Khan’s Palace,” Krym Realii, February 17, 2021, ru.krymr.com/a/novye-podriadchiki-dla-hanskogo-dvorca-rossiyskaya-restavraciya/31106315.html?fbclid=IwAR3BK03lJgyzZuGUIg0id78hDpUpleYeUw2CnJJk57C_pz_OgT-_nhYgrsk In a media interview, Crimean Tatar rights lawyer Emil Kurbedinov described the construction as “an unjustified attack on the historical heritage of the Crimean Tatars, a site of cultural heritage.”47“Facelift Or Farce? ‘Restoration’ Of Palace Shocks Crimean Tatars,” RFE/RL, February 18, 2018, rferl.org/a/crimea-khan-s-palace-restoration-bakhchisary-shock-tatars-persecution-unesco/29046866.html In February 2022, Russian authorities jailed Crimean Tatar civic activist and architect Edem Dudakov, who had been following the construction work closely, after he posted messages on Facebook criticizing the construction work.48Coynash, “Renowned Crimean Tatar civic activist jailed after exposing Russia’s destruction of 16th century Khan’s Palace.”

Attacks on Culture in Donetsk and Luhansk

Following the ouster of President Yanukovych and the unlawful occupation of Crimea, armed groups, backed by Russia, seized administrative buildings in several locations in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. In April 2014, they announced the establishment of the “Donetsk People’s Republic” (“DPR”) and the “Luhansk People’s Republic” (“LPR”), and took control of cities, towns, and villages in the regions.49“‘You Don’t Exist’: Arbitrary Detentions, Enforced Disappearances, and Torture in Eastern Ukraine,” Human Rights Watch, July 21, 2016, hrw.org/report/2016/07/21/you-dont-exist/arbitrary-detentions-enforced-disappearances-and-torture-eastern Russia expanded its campaign to erase Ukrainian culture, history, and language to these occupied territories, and to forcibly replace them with Russian language and Russian and Soviet history and culture. This effort has taken place in tandem with unchecked human rights abuses, including unlawful arrests, torture, sexual violence, disappearances, and looting of private property; threats against local officials, journalists, activists, and citizens, severely restricted communication; as well as—since February 2022—targeted and mass killings.50Since February 2022, there has been extensive documentation of human rights abuses in Russian-occupied territories recaptured by Ukraine, carried out by Ukrainian and international human rights organizations, and news media. For example, “Ukraine: Apparent War Crimes in Russia-Controlled Areas,” Human Rights Watch, April 3, 2022, hrw.org/news/2022/04/03/ukraine-apparent-war-crimes-russia-controlled-areas For documentation beginning in 2014, see: above, “Raw Fear in Separatist-Controlled Donetsk,” Human Rights Watch, November 28, 2016, hrw.org/news/2016/11/28/raw-fear-separatist-controlled-donetsk “Ukraine: Torture, Ill-Treatment by Armed Groups in the East,” Human Rights Watch, July 5, 2021, hrw.org/news/2021/07/05/ukraine-torture-ill-treatment-armed-groups-east Since 2014, Russian occupying forces have also blocked Ukraine’s cellphone network, internet, and media in areas they control. See: Adam Satariano, “How Russia Took Over Ukraine’s Internet in Occupied Territories,” New York Times, September 9, 2022, nytimes.com/interactive/2022/08/09/technology/ukraine-internet-russia-censorship.html

As part of this campaign, Russian forces have attacked writers, artists, and cultural workers who have spoken out against Russian occupation; imposed restrictions on displays of Ukrainian art, music, and other forms of culture; spread pro-Russian propaganda; deliberately destroyed cultural monuments; and controlled and manipulated the education system.

Russian forces have attacked writers, artists, and cultural workers who have spoken out against Russian occupation; imposed restrictions on displays of Ukrainian art, music, and other forms of culture; spread pro-Russian propaganda; deliberately destroyed cultural monuments; and controlled and manipulated the education system.

Repression of Artists, Writers, and Cultural Workers as a Tactic of Cultural Erasure

Since the unlawful occupation in 2014, writers, artists, and other cultural figures, especially those who criticize the occupation or separatist forces, have been illegally detained, imprisoned, and tortured in an effort to silence them and to stop them from writing and producing creative works.

In July 2014, occupation forces in Donetsk detained Serhiy Zakharov, who has been dubbed “the Banksy of Donetsk” for his irreverent street art, after he created and displayed public art mocking and criticizing the local authorities. “DPR” militants detained him and held him captive in his studio for over a month. He was repeatedly beaten and subject to mock executions. He wrote and illustrated a graphic novel describing his experience and that of other captives.51“’Донецький Бенксі’ готує книжку-комікс про своє перебування в полоні бойовиків [‘Donetsk Banksky’ is preparing a comic book about his captivity by militants],” Novoe Vremya, August 25, 2016, https://nv.ua/ukr/ukraine/events/donetskim-benksi-gotuje-knizhku-komiks-pro-svoje-perebuvannja-v-poloni-bojovikiv-65811.html (accessed September 9, 2022). Donetsk occupiers also illegally detained poet, writer, scientist, and public activist Ihor Kozlovsky for nearly two years from 2016 to 2017.52Kozlovsky Ihor, PEN Member, PEN Ukraine, accessed September 16, 2022, https://pen.org.ua/en/members/kozlovskyj-igor

The Ukrainian author and journalist Stanislav Aseyev, who reported on local developments for international news outlets under a pen name, Vasin, was detained in Donetsk in 2017 and illegally held for nearly two and a half years.53Aseyev’s memoir is The Torture Camp on Paradise Street. Andrew D’Anieri, “New book recounts prisoner torture in Russian-occupied eastern Ukraine,” Atlantic Council, November 16, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/new-book-recounts-prisoner-torture-in-russian-occupied-eastern-ukraine/ See also: “Militants of the People’s Republic of the People’s Republic of Ukraine are looting in the occupied center of modern art ‘Isolation,’” Lb.Ua, June 11, 2014, lb.ua/culture/2014/06/11/269435_boeviki_dnr_maroderstvuyut.html He wrote a book, The Torture Camp on Paradise Street, about his detention and abuse, in which he described the prison as “akin to a concentration camp where torture, humiliation, rape of both women and men, as well as forced hard physical labor are the rules of the day.”54Stanislav Aseyev and Andreas Umland, “‘Isolation’: Donetsk’s Torture Prison,” Harvard International Review, December 4, 2020, hir.harvard.edu/donetsks-isolation-torture-prison/

Since 2014, many writers, artists, and cultural workers have been forced to leave Russian-occupied territories or areas of active conflict for their own safety, escaping military conflict or repression or both, relocating to other locations in Ukraine and abroad.55Blair A. Ruble, “Providing Humanitarian and Creative Sanctuary for Artists in Ivano-Frankivsk,” Wilson Center, September 9, 2022, wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/providing-humanitarian-and-creative-sanctuary-artists-ivano-frankivsk Many have continued their creative work in very difficult circumstances,56Jane Arraf, “Lviv Reopens Galleries to ‘Show We are Alive,’” New York Times, May 7, 2022, nytimes.com/2022/05/07/world/europe/lviv-art-galleries.html but others have struggled to do so.

I realized that only one thing cannot be taken away from me by force: language and the ability to write.

Iya Kiva, poet

Iya Kiva, a poet, fled Donetsk in 2014 after the Russian invasion. She described being displaced in Ukraine and finding meaning as a writer during the war: “Left without a home, without property, without any prospects for the future, I realized that only one thing cannot be taken away from me by force: language and the ability to write . . . The most difficult thing for me was to convince myself that words, voice, poetry, [and] literature are still important. That they have not lost their meaning, but rather changed their meaning . . . The war speaks for itself so loudly and convincingly that all words next to it seem like incomprehensible noise . . . However, this is actually the task of literature in war, to restore weight to words—words of peace and love, so that all our testimonies outweigh the language of war.”57Iya Kiva, interview with staff of PEN America, August 2022 (email).

From 2010 to 2014 the Izolyatsia Foundation: Platform for Cultural Initiatives operated on the site of a former insulating materials factory. During the first years of the foundation, more than 20 art projects were created. Well-known Ukrainian and foreign artists including Cai Guo-Qiang, Daniel Buren, Borys Mykhailov, and Lozano-Hemmer worked there, alongside promising young Ukrainian artists like Zhanna Kadyrova, Apl315, Roman Minin, Ivan Svitlychny, Gamlet Zinkivsky, and others.

On June 9, 2014, armed representatives of the “DPR” invaded the Foundation and converted it into a training facility for “DPR” fighters; a depot for automobiles, military technology, and weapons; a prison; and a secret torture facility. Former prisoners have remarked that the Izolyatsia buildings were not equipped to serve as a prison, and that its conditions more closely resembled those of a concentration camp. Prisoners were forced to work for the wardens, who regularly used physical violence, and were deprived of food, water, and medical care.58D’Anieri, “New book recounts prisoner torture in Russian-occupied eastern Ukraine,” Atlantic Council.

The Manipulation of Culture and Identity Through Education

Russian and separatist forces use education as a key vehicle for Russification efforts in occupied regions. Following their takeover in the “DPR,” separatist authorities attempted to return the region to a Russian and Soviet system of education, prohibiting teaching in Ukrainian in schools.59Illya Trebor, “How Education is being Re-shoveled in Donetsk,” Radio Svoboda, September 23, 2014, https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/26602689.html (accessed September 14, 2022). Teachers were given the option of retraining to teach in Russian,60Halya Coynash, “Russia-controlled Donbas ‘republics’ remove Ukrainian language from schools,” The Ukrainian Weekly, September 27, 2019, ukrweekly.com/uwwp/russia-controlled-donbas-republics-remove-ukrainian-language-from-schools/ but teachers of Ukrainian language and literature in the “DPR” and “LPR” lost their jobs. At the university level, “DPR” authorities dismissed rectors of several universities and eliminated the department of Ukrainian history.61Illya Trebor, “How Education is being Re-shoveled in Donetsk,” Radio Liberty.

Seizure and Destruction of Books

The cultural erasure campaign has also involved seizing and destroying Ukrainian literature and Ukrainian-language books. Beginning in March 2022, occupying authorities seized or destroyed Ukrainian history books and literature they deemed to be “extremist” from public libraries in cities and towns in the occupied territories of Luhansk, Donetsk, Chernihiv, and Sumy, according to the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine. This included books about Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity in 2013-2014, Ukrainian liberation movements, Ukraine’s military operations against separatists in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, and, in some locations, the nonfiction book, The Case of Vasyl Stus, about a Ukrainian poet who was imprisoned by the Soviet regime.62Jon Jackson, “Ukraine Claims Russian Military Police Are Destroying Their History Books,” Newsweek, March 24, 2022, newsweek.com/ukraine-claims-russian-military-police-are-destroying-their-history-books-1691559 “Russians Confiscating and Destroying Ukrainian Literature and History Textbooks,” Chytomo, March 25, 2022, https://chytomo.com/en/russians-confiscating-and-destroying-ukrainian-literature-and-history-textbooks/ On the Holodomor: “Worldwide Recognition of the Holodomor as Genocide, Holodomor Museum, holodomormuseum.org.ua/en/recognition-of-holodomor-as-genocide-in-the-world/

Also in March, separatist authorities in the “DPR” announced the seizure of books on history, politics, Ukrainian national movements, state symbols of Ukraine, and religion in 70 libraries.63“Терористи «ДНР» вилучають «екстремістську літературу» з окупованих міст [‘DNR’ Terrorists Remove ‘Extremist Literature,’ from occupied territories], Chytomo, May 25, 2022, chytomo.com/terorysty-dnr-vyluchaiut-ekstremistsku-literaturu-z-okupovanykh-mist/

In the small town of Borova, in the Kharkiv region, local officials reported in July that “Ukrainian state symbols and Ukrainian textbooks are being destroyed in schools.”64Borova Ukrainian local council, Telegram channel, July 25, 2022, t.me/borova_gromada/1115 Occupying forces replaced seized books with textbooks imported from Russia, including those that teach students that Russia is their homeland and that although many ethnic groups exist in Russia, there is no distinct Ukrainian cultural identity.65Petro Andriushchenko, advisor to the Ukrainian mayor of Mariupol, Telegram channel, September 13, 2022, t.me/andriyshTime/2890

Ukrainian Culture on the Frontlines

Russia launched a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. The war has caused untold suffering to the Ukrainian people, undermining their rights to life and physical security, and infringing on their access to housing, health care, education, food, and water. Russian attacks have also damaged vital infrastructure and inflicted enormous damage on Ukraine’s environment. As of November 14, 2022, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has verified a total of 16,631 civilian casualties, with 6,557 civilian deaths since February 24, 2022. The majority of civilian casualties were caused by the use of explosive weapons with wide area effects, “including shelling from heavy artillery, multiple launch rocket systems, missiles, and air strikes.” OHCHR believes the actual number of casualties, including deaths, is likely much higher.66OHCHR, “Ukraine civilian casualty update,” November 14, 2022, https://www.ohchr.org/en/news/2022/11/ukraine-civilian-casualty-update-14-november-2022

Since the outbreak of conflict in 2014 and particularly since the 2022 invasion, Ukraine has experienced massive population displacement: As of October 21, 2022, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that more than 6.2 million Ukrainians are internally displaced, while 7.7 million more have fled the country, overwhelmingly to Poland, Slovakia, Moldova, and Romania.67UNHRC, “Ukraine Situation Flash Update #33”, October 21, 2022, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/96361

The conflict has also had a devastating impact on the Ukrainian cultural community. Writers, artists, and cultural workers are among those killed and seriously injured. Others have given up their cultural work and joined the military forces to defend Ukraine, where some have lost their lives and others continue to fight.68Kateryna Volkova, “Life As a Book Publisher in Wartime Ukraine,” Literary Hub<, May 12, 2022, lithub.com/life-as-a-book-publisher-in-wartime-ukraine/ “People of Culture Taken Away by the War,” PEN Ukraine Last Updated October 24, 2022, pen.org.ua/en/lyudy-kultury-yakyh-zabrala-vijna Jason Farago, “The War in Ukraine is a True Culture War,” New York Times, Updated July 17, 2022, nytimes.com/2022/07/15/arts/design/ukraine-war-culture-art-history.html PEN Ukraine’s webpage, “People of Culture Taken Away by the War,” most recently updated on October 24, 2022, documents 31 civilian artists, writers, and other cultural workers killed as a result of Russian military attacks as well as a number of cultural figures killed in combat while defending Ukraine.69“People of Culture Taken Away by the War,” PEN Ukraine. Their loss is incalculable.

Russian military attacks have damaged or destroyed hundreds of cultural buildings and objects, including museums, theaters, monuments, statues, places of worship, cemeteries, historical buildings, libraries, archives, as well as schools and universities.

Damage to and Destruction of Cultural Heritage

The destruction of Ukrainian cultural infrastructure and cultural heritage sites has been a significant component of Russia’s assault on Ukraine since February 2022. Russian military attacks have damaged or destroyed hundreds of cultural buildings and objects, including museums, theaters, monuments, statues, places of worship, cemeteries, historical buildings, libraries, archives, as well as schools and universities. Russian attacks have also damaged or destroyed local cultural centers (“houses of culture”), concert venues and stadiums, and other locations where people access culture in their communities.

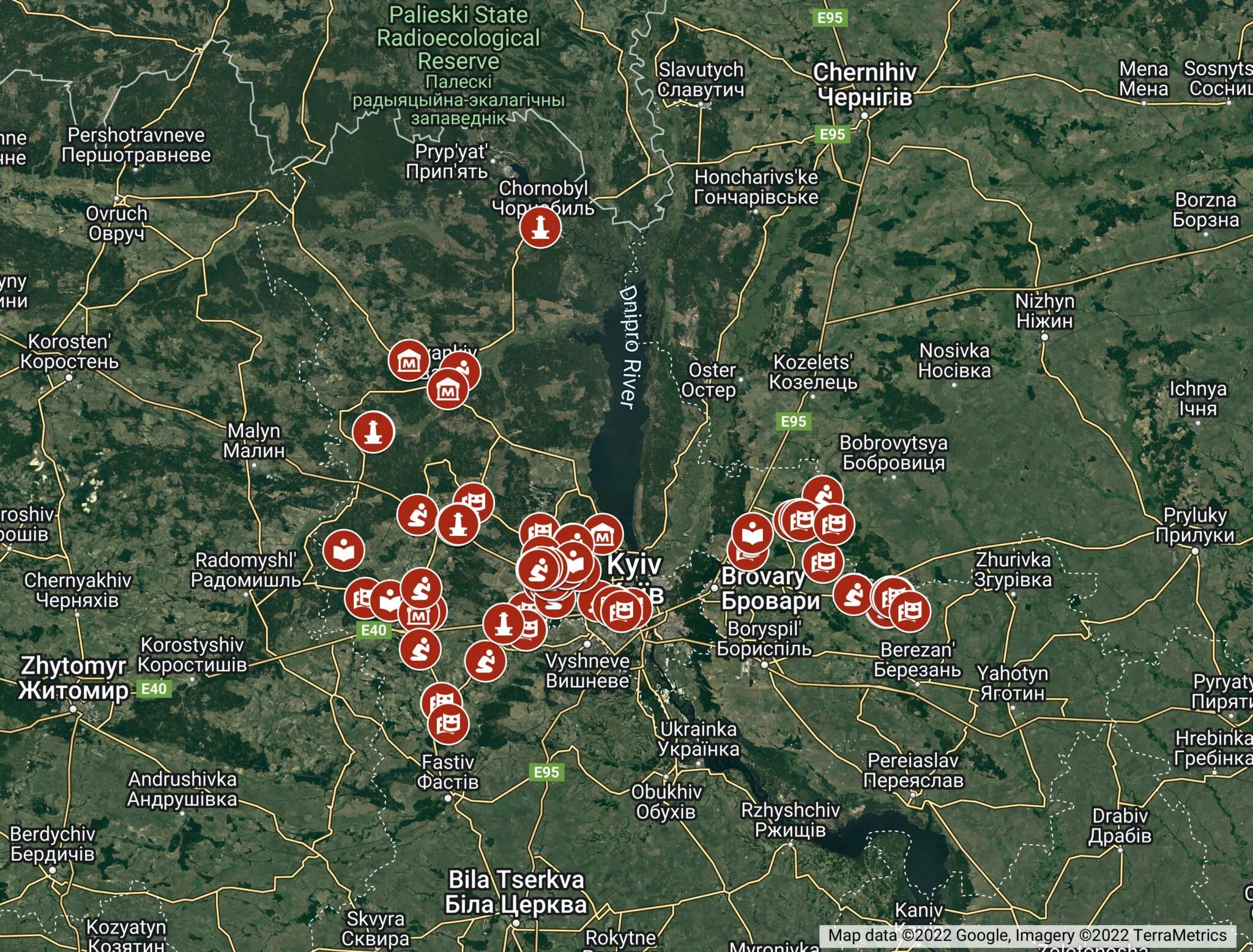

As of November 17, 2022, the Ukrainian government has documented 529 damaged and destroyed “objects of cultural heritage and cultural institutions of Ukraine” in 11 regions.70“Destroyed Cultural Heritage of Ukraine,” Ministry of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine, regularly updated, accessed November 17, 2022, culturecrimes.mkip.gov.ua/ As of October 31, UNESCO has verified damage to 210 sites, including 91 religious sites, 15 museums, 76 buildings of historic or artistic significance, 18 monuments, and 10 libraries.71“Damaged cultural sites in Ukraine verified by UNESCO,” UNESCO, October 24, 2022, unesco.org/en/articles/damaged-cultural-sites-ukraine-verified-unesco

It describes its methodology as: “UNESCO is conducting a preliminary damage assessment for cultural properties [as defined by the 1954 Hague Convention] by cross-checking the reported incidents with multiple credible sources.”

The United States-based Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab (CHML) and the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative (SCRI) have been monitoring 28,000 cultural sites in Ukraine through a combination of remote sensing, open-source research, and satellite imagery.72“Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Potential Impact Summary,” Virginia Museum of Natural History, Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab, and Smithsonian Institution, Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative, May 9 2022, hub.conflictobservatory.org/portal/sharing/rest/content/items/6b7c5f0225f64d82b33c2abf63fe72f5/data Researchers identified over 458 incidents of potential damage to cultural heritage sites from February 24 to May 9, 2022, including archaeological sites, arts centers, monuments, memorials, museums, places of worship, libraries, and archives. They found that memorials and places of worship have sustained the highest rates of potential impact and that incidences were most frequent in or near the cities of Mariupol and Kharkiv.73“Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Potential Impact Summary.” They subsequently confirmed damage to 104 sites through analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery and a review of open-source news and social media.74“Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Potential Impact Summary.”

In some cases, the damage or destruction to cultural sites was likely a result of indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks by the Russian forces. Russia’s military operation has been characterized as regular and repeated sweeping attacks on densely populated civilian areas resulting in massive damage to civilian houses, hospitals, schools, and other civilian infrastructure, as well as deaths and injury.75As documented by Ukrainian and international human rights organizations. See for example, “No mercy for civilians: Troubling accounts from the MSF medical train in Ukraine,” MSF, June 22, 2022, msf.org/data-and-patient-accounts-reveal-indiscriminate-attacks-against-civilians-ukraine-war Russia has utilized explosive weapons with wide-area affects such as air-dropped bombs, missiles, heavy artillery shells, and multiple launch rockets. It has also used cluster munitions that typically open in the air and send dozens, even hundreds, of small bomblets over an extensive area.76In a July report, an OSCE-appointed expert mission found: “the magnitude and frequency of the indiscriminate attacks carried out against civilians and civilian objects, including in sites where no military facility was identified, is credible evidence” that Russian armed forces disregarded “their fundamental obligation to comply with the basic principles of distinction, proportionality and precaution that constitute the fundamental basis of IHL.” Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, “Report on Violations of International Humanitarian Law, War Crimes, Crimes against Humanity Committed in Ukraine April 1-June 25, 2022,” July 14, 2022, osce.org/files/f/documents/3/e/522616.pdf

These attacks, whether targeted or the result of indiscriminate assaults on civilian infrastructure, are prohibited under international law, and may constitute war crimes, as described in more detail below. Bellingcat, an independent forensic research organization, conducted an in-depth analysis of attacks on five cultural sites in Ukraine using open-source information. They determined that while “it is often hard to conclusively establish intent behind . . . attacks that have led to the damage or destruction of cultural sites . . . the sheer number of cultural sites damaged or under threat indicates that it is highly unlikely they are being excluded from Russia’s bombardment.”77“Report on Violations of International Humanitarian Law, War Crimes, Crimes against Humanity Committed in Ukraine April 1-June 25, 2022,” The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) has also raised concerns about the “large-scale destruction of civilian objects.”78“Report on Violations of International Humanitarian Law, War Crimes, Crimes against Humanity Committed in Ukraine April 1-June 25, 2022,”

Targeted Attacks

Local Museums

In a June report, CHML, SCRI, and University of Maryland’s Center for International Development and Conflict Management (CIDCM), identified 10 sites, including four local museums, that sustained damage that cannot be explained by their proximity to potential military targets,79“[D]amaged cultural heritage sites distant (>3km) from ongoing conflict activity, Ukrainian bases or stationary military assets, and dual-use transportation infrastructure (e.g., train stations, railways, airfields, and airports) are unlikely to be damaged as a consequence of military activity. “Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Potential Impact Summary.” suggesting that the sites may have been specifically targeted. The damage to and destruction of these small, local museums represent a particular cultural loss to local residents, which may be irreplaceable if their holdings are not fully cataloged.

One of the museums identified in the report by CHML, SCRI, and CIDCM is the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum, established in 1981 and located about 50 miles north of Kyiv. Their holdings include art and artifacts relevant to the history and culture of the village of Ivankiv. On February 26, Russian troops shelled the museum, and no other targets in Ivankiv. At the time of its destruction, the museum served as a repository for a collection of paintings by Maria Prymachenko, a Ukrainian painter and former resident of the Ivankiv district. Prymachenko’s paintings were rescued by local citizens.

Similarly, a Russian missile strike on May 6 hit the Hryhoriy Skovoroda National Literary Memorial Museum in the Kharkiv region and caused a fire, according to CHML, SCRI, and CIDCM.80“Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Potential Impact Summary.” See also the analysis by Bellingcat of the attack on the Skovoroda museum.

Skovoroda was an 18th-century Ukrainian poet, philosopher, and teacher, and he has a prominent legacy, with several Ukrainian universities named after him and his image appearing on the 500 hryvnia note. Volodymyr M. Lopatko is an assistant professor of civil engineering and architecture at Kharkiv National University of Civil Engineering and Architecture and was interviewed by a videographer working with PEN America. He described Skovoroda: “The point is . . . [in the 18th century] it was difficult to talk about rights. Skovoroda came up with a peculiar language . . . he wrote fables. And he could explain these relationships using allegory, birds, [and] animals. He had a mystical and religious belief in the equality of people . . . And his idea that all unequal people should be equal became the basis of his religious and mystical idea of humanity.”81Volodymyr M. Lopatko, in person interview with videographer of PEN America, October 10, 2022 Lopatko also explained the importance of the site: “There are not many places in the world where one can find so much information about Skovoroda.”82Lopatko, interview with PEN America.

Although manuscripts and other items in the museum’s collection had been removed to protect them, the building sustained significant damage. Lopatko explained efforts to save the building: “There is no roof, but we are trying to cover the walls with cellophane.”83Lopatko, interview with PEN America. Poignantly, a statue of Skovoroda survived the attack almost unscathed.84Torsten Landsberg, “Who was Ukrainian philosopher Hryhoriy Skovoroda?” DW, May 12, 2022 dw.com/en/who-was-ukrainian-philosopher-hryhoriy-skovoroda/a-61760549 “Ukraine’s Zelenskiy ‘speechless’ after shelling destroys museum dedicated to poet,” Reuters, May 7, 2022, reuters.com/world/europe/shelling-destroys-museum-dedicated-famous-ukrainian-philosopher-regional-2022-05-07/

The CHML, SCRI, CIDCM report also identified the City Museum in Rubizhne that houses a collection of art and artifacts relevant to local history and culture, as a targeted attack. It was struck by Russian forces during fighting in March 2022 in the Luhansk region.85“Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Potential Impact Summary.”

Similarly, the Izyum Local Lore Museum in the Kharkiv region was struck in late February or early March. The museum was established in 1920 to “preserve the historical and cultural heritage and spread knowledge” through a collection of books, paintings, and works of art relevant to the history of the region.86“Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Potential Impact Summary. See also, the museum website: “Izyum Local Lore Museum named after M.V. Sibilova,” accessed September 12, 2022, kultura-izyum.gov.ua/uk/site/kraeznavchii-muzey.html” According to the museum’s website, it was destroyed once before, during World War II, with significant losses to its collection.87Izyum Local Lore Museum named after M.V. Sibilova.

Monument to Shevchenko in Borodianka

In Borodianka, a town near Kyiv, Russian shelling heavily damaged a monument to Taras Shevchenko. The statue remained standing despite the damage. Following the town’s liberation by Ukrainian forces in early April, Yaroslav Holubchyk, an artist from Kyiv, wrapped a big gauze bandage around the bust’s giant head as an impromptu art project called “The Healing of Shevchenko.”88Scott Detrow, Kat Lonsdorf, Noah Caldwell, and Nikolai Hammar, “This is what one town in Ukraine looks like after Russian troops withdrew,” National Public Radio, April 9, 2022, npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2022/04/09/1091740132/ukraine-russia-borodyanka

Mariupol Drama Theater

From the start of Russia’s 2022 invasion, the Russian military has relentlessly shelled the port city of Mariupol.89“Mariupol: Key moments in the siege of the city,” BBC, May 17, 2022, bbc.com/news/world-europe-61179093 On March 16, Russian aircraft dropped two 500kg bombs on the Academic Regional Drama Theater in Mariupol, where hundreds of residents were sheltering. The bombs caused the roof and large parts of the walls to collapse.90“Ukraine: Deadly Mariupol Theater Strike a Clear War Crime by Russian Forces,” Amnesty International, June 2022, amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/06/ukraine-deadly-mariupol-theatre-strike-a-clear-war-crime-by-russian-forces-new-investigation/ The Russian word for “children” appeared written twice in large Cyrillic script in front of and behind the theater, clearly visible to aircraft, indicating that children were sheltering in the building. According to the Mariupol City Council, approximately 300 people died in the attack.91Mariupol Ukrainian Local Council, Telegram Channel, March 25, 2022, ht.me/mariupolrada/8999 An expert mission under the auspices of the OSCE concluded that: “[T]his incident constitutes most likely an egregious violation of IHL and those who ordered or executed it committed a war crime.”92Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, “Report on Violations of International Humanitarian Law, War Crimes, Crimes against Humanity Committed in Ukraine Since February 24 2022,”, April 12, 2022, osce.org/files/f/documents/f/a/515868.pdf, Amnesty International also determined the attack to be a war crime: Amnesty International, “Ukraine: Deadly Mariupol Theater Strike a Clear War Crime by Russian Forces.” https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/06/ukraine-deadly-mariupol-theatre-strike-a-clear-war-crime-by-russian-forces-new-investigation/ In the context of other seemingly targeted attacks on cultural institutions, it seems likely that the theater was targeted for its cultural significance.

Indiscriminate and Disproportionate Attacks

Indiscriminate attacks by Russian forces have decimated cultural infrastructure and heritage across Ukraine, causing destruction and damage to museums, libraries, and historically important buildings.

Kuindzhi Art Museum

One of the sites examined by Bellingcat was the Kuindzhi Art Museum in Mariupol. During the Russian siege of the city,93“Mariupol: Key moments in the siege of the city,” BBC, May 17, 2022, bbc.com/news/world-europe-61179093 an airstrike damaged the landmark Art Nouveau building on March 20, 2022, destroying some artworks.94Tessa Solomon, “Mariupol Museum Dedicated to Ukrainian Painter Reportedly Destroyed in Russian Airstrike,” ArtNews, March 24, 2022 artnews.com/art-news/news/kuindzhi-art-museum-destroyed-ukraine-war-1234622834/ The museum commemorates the work and life of Arkhip Kuindzhi, a prominent landscape painter of Greek descent who was born locally. The museum contained works by other 20th-century Ukrainian painters as well as a library and historical archive. A nearby museum of local lore was also damaged by Russian attacks.95Maxim Edwards, “Clues to the Fate of Five Damaged Cultural Heritage Sites in Ukraine,” Bellingcat, June 7, 2022, bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2022/06/07/clues-to-the-fate-of-five-damaged-cultural-heritage-sites-in-ukraine/

Attacks on Buildings With Religious or Spiritual Significance

Dozens of churches, mosques, synagogues, cemeteries, and other buildings with religious and spiritual significance have been damaged and destroyed since February 2022. The Ukrainian government has documented at least 160 attacks on religious sites.96“Places of Worship: Destroyed Cultural Heritage of Ukraine,” Ministry of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine, as of September 17, 2022 (regularly updated) culturecrimes.mkip.gov.ua/?paged=17&cat=3 The Sviatohirsk Lavra, a historic Orthodox Christian cave monastery complex built between the 17th and 19th centuries in the Donetsk region, came under repeated attacks between March and June.97Maxim Edwards, “Clues to the Fate of Five Damaged Cultural Heritage Sites in Ukraine.” According to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, at the time of an air attack on March 12, 520 people were sheltering at the monastery and some were injured by shrapnel.98Maxim Edwards, “Clues to the Fate of Five Damaged Cultural Heritage Sites in Ukraine.” The historic wooden All Saints’ church in the complex was burned completely, apparently having been struck by artillery.99Maxim Edwards, “Clues to the Fate of Five Damaged Cultural Heritage Sites in Ukraine.” Ukraine’s Minister of Culture Oleksandr Tkachenko said that there were monks and nuns, as well as about 300 others, seeking shelter in the complex at the time of the strike.100OSCE, “Report on Violations of International Humanitarian Law, War Crimes, and Crimes Against Humanity Committed in Ukraine, April 1 to June 25, 2022.”

In July 2022, occupying forces in Mariupol set fire to the book collection of the Russian Orthodox Church of Petro Mohyla, which contained “several unique copies of Ukrainian-language publications.”101“In Mariupol, occupiers burned all the books from the library of the church of Petro Mohyla,” Holodomor Museum, June 27, 2022, holodomormuseum.org.ua/en/news/in-mariupol-the-occupiers-burned-all-the-books-from-the-library-of-the-church-of-petro-mohyla/ Petro Andriushchenko, advisor to the mayor of Mariupol, Telegram channel, June 25, 2022, t.me/andriyshTime/1593 The church served as an important center for Ukrainian culture, as well as a charitable center. The destruction and confiscation of books pose a particularly severe threat to unique, rare, and archival documents, which often exist only in their original.

Local Cultural Centers

Russian attacks have also damaged dozens of local cultural centers (“houses of culture”), music venues, and stadiums that function as important community and cultural spaces.

On May 20, 2022, the community cultural center in Lozova, near Kharkiv, called the Palace of Culture, received a direct hit. According to the government, at least seven people, including an 11-year-old child, were injured. The executive director of the center, Victor Haraschuk, had fortuitously sent most of his staff home an hour before the strike. He returned to the center after the attack and confirmed the number of injuries and said that “they were simply thrown back by the blast wave.”102Victor Haraschuk, interview with videographer of PEN America, October 9, 2022

The center, the only major cultural institution in the area, housed an auditorium, a lecture hall, three dance halls, a gym, a large library, and multiple rooms for classes and club meetings.103“Strike Devastates Palace of Culture in Ukrainian City of Lozova,” Yahoo News, May 20, 2022, news.yahoo.com/strike-devastates-palace-culture-ukrainian-162610156.htmlTaylor Dafoe, “Kharkiv’s Palace of Culture Was Destroyed by a Russian Missile Attack, Leaving Eight Injured,” Artnet News, May 24, 2022, news.artnet.com/art-world/a-ukrainian-palace-of-culture-in-kharkiv-destroyed-2120574

In an interview with a videographer working with PEN America, Haraschuk described the importance of the center to the community: “It was a cultural center of our urban community, the heart of our city. There is not a single person who is not somehow connected with the Palace of Culture. Either their children studied here, or they themselves worked or studied here. Everyone knew the Palace of Culture. This is the soul of our city . . . The Palace is important for the city; the city needs it very much. Now we have nothing, no halls or theaters. It was the crucial center of culture.”104Haraschuk, interview. Haraschuk estimated that about 70 percent of the center’s equipment had been damaged or completely destroyed, including stage and sound equipment. Staff members were also not able to save any books.105Haraschuk, interview.

Haraschuk could not understand why the Palace of Culture was struck: “There was no military here, nothing related to the military. We had only a small tractor we used to transport scenery for Palace maintenance. That’s all. I don’t understand why this happened. Maybe because it is a very beautiful, freestanding building.”106Haraschuk, interview. PEN America could not confirm whether this was indeed a targeted attack.

Human Rights Watch documented two Russian strikes on the Derhachi cultural center. The first, on May 12, 2022, pierced the building’s roof and injured two volunteers who were preparing food and other aid for local residents. The second, in the early morning hours of May 13, 2022, struck while 21 people were sheltering there overnight.107“Ukraine: Unlawful Russian Attacks in Kharkiv,” Human Rights Watch, August 16, 2022, hrw.org/news/2022/08/16/ukraine-unlawful-russian-attacks-kharkiv

Everyone knew the Palace of Culture. This is the soul of our city . . . The Palace is important for the city; the city needs it very much. Now we have nothing, no halls or theaters. It was the crucial center of culture.

Victor Haraschuk, executive director of the Palace of Culture

Bellingcat recorded damage to several cultural centers in Mariupol in the Donetsk region on March 16 2022; in Irpin on March 24, 2022; and in Chuhuyiv in the Kharkiv region on July 25, 2022.108“Civilian Harm in Ukraine,” Bellingcat, as of September 19, 2022 (regularly updated), accessed September 17, 2022, ukraine.bellingcat.com/ The Ukrainian government has also documented dozens of strikes to cultural centers.109“Destroyed Cultural Heritage of Ukraine,” Ministry of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine, as of September 17, 2022, culturecrimes.mkip.gov.ua/

Libraries and Archives

The Ukrainian government has documented damage and destruction to at least 49 libraries and archives.110“Libraries, Destroyed Cultural Heritage of Ukraine,” Ministry of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine, as of September 17, 2022, culturecrimes.mkip.gov.ua/?paged=4&cat=7 In an August media interview, Oksana Boyarynova, a member of the Ukrainian Library Association Board, reported that 2,475 libraries, out of about 15,000 across the country, are currently closed due to damage, funding, or staff being forced to leave their jobs and homes due to the war. She said that 21 libraries have lost their entire collections.111Jane Bradley, “How Ukraine’s Librarians Mobilized to Fight the Russian Culture War,” The Scotsman, August 7, 2022, scotsman.com/news/world/how-ukraines-librarians-mobilised-to-fight-the-russian-culture-war-3796419

The city of Chernihiv was subject to an intense siege by Russian forces from February 24 until their withdrawal from northern Ukraine in early April.112Maxim Edwards, “Clues to the Fate of Five Damaged Cultural Heritage Sites in Ukraine,” Bellingcat, June 7, 2022, bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2022/06/07/clues-to-the-fate-of-five-damaged-cultural-heritage-sites-in-ukraine Joshua Yaffa, “The Siege of Chernihiv,” NewYorker.com, April 15, 2022, newyorker.com/news/dispatch/the-siege-of-chernihiv Russian attacks decimated the striking Gothic Revival Youth Library, also known as the Tarnovsky Building, causing extensive damage to its roof and walls.113“Chernihiv Library for Youth,” Ukrainian Institute, accessed September 17, 2022, ui.org.ua/en/sectors-en/museum-of-ukrainian-antiquities-2/ The building formerly housed the Museum of Ukrainian Antiquities: Founded in 1902 by Vasyl Tarnovsky, it was one of the first and one of the most well-known museums in Ukraine. The collection had been transferred to the city historical museum and the building subsequently functioned as a library for children and youth, including at the time of the attack. The Ukraine Institute describes the damage as “an irreparable loss of the cultural and historical heritage of Ukraine.”114“Chernihiv Library for Youth,” Ukrainian Institute.

Also in the Chernihiv region, Ukraine’s Ministry of Justice, citing the head of the State Archival Service of Ukraine, reported that Russian attacks destroyed the Security Service archives, which included the former Soviet secret police (NKVD) documents related to Soviet repression against Ukrainians.115Denys Dratsky, ed., “Russian occupiers launch war on Ukrainian history, burning books, and destroying archives,” Euromaidan Press, April 2, 2022, euromaidanpress.com/2022/04/02/russian-occupiers-launch-war-on-ukrainian-history-burning-books-and-destroying-archives/ Approximately 13,000 files were destroyed, representing a devastating loss to historians and to the victims whose stories the documents held.116“Russians in Ukraine Burn Books, Destroys Libraries, Archives, Theaters,” Poland Daily Live, April 30, 2022, youtube.com/watch?v=k-5oAbxu7j0

Russian forces attacked Bucha, a small city outside of Kyiv, committing grave human rights abuses, including mass killings of civilians. They also destroyed the archives of the Ukrainian politician and Soviet-era dissident, politician, and publicist, Vyacheslav Chornovil.117“In Bucha, Russian invaders destroyed the Vyacheslav Chornovil Archive,” Ukrinform, April 4, 2022, ukrinform.ru/rubric-culture/3462256-v-buce-rossijskie-zahvatciki-unictozili-arhiv-vaceslava-cornovila.html SPILKA News, “The occupiers attacked the archive of Vyacheslav Chornovil,” Telegram Channel, April 19, 2022, t.me/spilkanews/669 As a defender of Ukrainian cultural rights and free expression, Chornovil publicized the Soviet repression of Ukrainian intellectuals in 1966; headed the Ukrainian Helsinki monitoring group; edited the Ukrainian Herald, an illegal underground newspaper; and was head of the Ukrainian national-democratic liberation movement in the late ’80s and ’90s. Chornovil was sentenced to Soviet prison three times before emerging as a prominent political leader after Ukraine’s independence.118Peter Marusenko, “Vyacheslav Chornovil obituary,” The Guardian, April 15, 1999, theguardian.com/news/1999/apr/16/guardianobituaries The National Union of Journalists reported that significant parts of Chornovil’s archive were lost, as well as books from the Chornovil Foundation and 60 copies of the complete works of Chornovil. Nearly all of the archives of Mykola Plahotniuk, a fellow dissident, located in the same house, were also destroyed.119“In Bucha, Russian invaders destroyed the Vyachislav Chornovil Archive,” Ukrinform, and “The occupiers attacked the archive of Vyacheslav Chornovil,” Telegram Channel.