Treating Online Abuse Like Spam

How platforms can reduce exposure to abuse while protecting free expression

PEN America Experts:

Program Manager, Cybersecurity Research at Consumer Reports

Assistant Professor, Computer Science & Engineering at UC San Diego

Director, Digital Safety and Free Expression

Summary

Online abuse is a widespread and very real problem. According to a 2021 study by the Pew Research Center, nearly half of Americans have experienced online harassment,1Emily Vogels, “The State of Online Harassment,” Pew Research Center, January 13, 2021, pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/; see also Kurt Thomas et al., “SoK: Hate, Harassment, and the Changing Landscape of Online Abuse,” 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, May 2021, 247-267, ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9519435. which can damage mental health, cause self-censorship, and even put lives at risk. For public-facing professionals—such as journalists, scholars, politicians, and creators—the rates of exposure are even higher. Yet technology companies, including social media platforms, are not sufficiently investing in mechanisms that alleviate the harms of online hate and harassment. They remain overly reliant on reactive solutions, which require users to encounter online abuse–often repeatedly–before it can be addressed, rather than investing in solutions that proactively reduce exposure to abuse while protecting free expression.

In this report, we set out to explore an innovative idea that first emerged in 2018: What would happen if technology companies treated online abuse more like spam? In other words, what if platforms empowered individual users with a mechanism that automatically detected potentially abusive content proactively and quarantined it, so that users could then choose to review and address it—or ignore it altogether? We examine the pros, cons, and nuances involved in this proposal, from both a technical and sociocultural standpoint. We conclude with a detailed set of recommendations outlining how technology companies can implement proactive abuse mitigation mechanisms like the one proposed here. We intend this report to guide technologists, policy experts, trust and safety experts, and researchers who are committed to reducing the negative impacts of online abuse in order to make online spaces safer, more equitable, and more free.

Introduction

Online abuse chills free expression

Online abuse is making public discourse, so much of which now plays out in digital spaces, less equitable and less free. Malicious actors, ranging from disaffected trolls to state-sponsored cyber-armies, deploy violent threats, hateful slurs, sexual harassment, doxing, and other abusive tactics to intimidate, discredit, and silence their targets.2In this report, we use the terms “online abuse” and “online harassment” interchangeably; PEN America defines these terms as the “pervasive or severe targeting of an individual or group online through harmful behavior.” “Defining ‘Online Abuse’: A Glossary of Terms,” Online Harassment Field Manual, PEN America, onlineharassmentfieldmanual.pen.org/defining-online-harassment-a-glossary-of-terms/.

These tactics are pervasive. According to a 2021 study from the Pew Research Center, 41% of regular users in the U.S. have experienced online harassment, and the volume and severity of such attacks are increasing. People are often targeted because of their profession, identity, and/or political beliefs.3Emily Vogels, “The State of Online Harassment,” Pew Research Center, January 13, 2021, pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/; see also Kurt Thomas et al., “SoK: Hate, Harassment, and the Changing Landscape of Online Abuse,” 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, May 2021, 247-267, ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9519435. Online abuse disproportionately impacts those whose voices have been historically marginalized: women,4Marjan Nadim and Audun Fladmoe, “Silencing Women? Gender and Online Harassment,” Social Science Computer Review 39, no. 2 (July 30, 2019), 245-258, journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0894439319865518; see also Emily Vogels, “The State of Online Harassment,” Pew Research Center, January 13, 2021, pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/. people of color,5Maeve Duggan, “1 in 4 Black Americans Have Faced Online Harassment Because of Their Race or Ethnicity,” Pew Research Center, July 25, 2017, pewresearch.org/short-reads/2017/07/25/1-in-4-black-americans-have-faced-online-harassment-because-of-their-race-or-ethnicity/; see also Emily Vogels, “The State of Online Harassment,” Pew Research Center, January 13, 2021, pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/. LGBTQ+ individuals,6Abreu, R.L., & Kenny, M.C., “Cyberbullying and LGBTQ Youth: A Systematic Literature Review and Recommendations for Prevention and Intervention,” Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11(1) (2017), 81-97. doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0175-7. and members of religious or ethnic minorities.7Niloufar Salehi et al., “Sustained Harm Over Time and Space Limits the External Function of Online Counterpublics for American Muslims,” ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 7, no. 93 (April 2023), 1-24, dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3579526; Brooke Auxier, “About One-in-five Americans Who Have Been Harassed Online Say It Was Because of Their Religion,” Pew Research Center, February 1, 2021, pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/02/01/about-one-in-five-americans-who-have-been-harassed-online-say-it-was-because-of-their-religion/. It is particularly pernicious for people who need to have an online presence to do their jobs, including journalists,8Ferrier, M.P.B. (2018). “Attacks and Harassment: The Impact on Female Journalists and their Reporting,” TrollBusters and the International Women’s Media Foundation, https://www.iwmf.org/attacks-and-harassment/; Lucy Westcott, “‘The threats follow us home’: Survey details risks for female journalists in U.S., Canada,” Committee to Protect Journalists, September 4, 2019, cpj.org/2019/09/canada-usa-female-journalist-safety-online-harassment-survey/; Julie Posetti and Nabeelah Shabbir, “The Chilling: A Global Study On Online Violence Against Women Journalists,” International Center for Journalists, November 2, 2022, icfj.org/our-work/chilling-global-study-online-violence-against-women-journalists; Michelle Ferrier and Nisha Garud-Patkar, “TrollBusters: Fighting Online Harassment of Women Journalists,” Mediating Misogyny (2018): 311-332. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72917-6_16. academics and researchers,9Atte Oksanen, Magdalena Celuch, Rita Latikka, Reetta Oksa, and Nina Savela, “Hate and Harassment in Academia: The Rising Concern of the Online Environment,” Higher Education 84 (November 23, 2021): 541–567, doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00787-4; Naomi Nix, Joseph Menn, “These Academics Studied Falsehoods Spread by Trump. Now the GOP Wants Answers,” The Washington Post, June 6, 2023, washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/06/06/disinformation-researchers-congress-jim-jordan/; Bianca Nogrady, “‘I Hope You Die’: How the COVID Pandemic Unleashed Attacks on Scientists,” Nature, October 13, 2021, nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02741-x. and content creators.10Kurt Thomas, Patrick Gage Kelley, Sunny Consolvo, Patrawat Samermit, and Elie Bursztein, “‘It’s Common and a Part of Being a Content Creator’: Understanding How Creators Experience and Cope with Hate and Harassment Online,” CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, no. 121 (April 27, 2022), 1-15, dl.acm.org/doi/fullHtml/10.1145/3491102.3501879.

Online harassment is an especially prevalent problem for women journalists—a 2022 study from UNESCO and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) found that 73% of women respondents had experienced it. Such tactics can take a serious toll on mental health, and, in some cases, even migrate offline. As part of the aforementioned study, 20% of women journalists reported that they had been attacked offline in incidents connected to online abuse. Given the severity and level of risk, online harassment can be extremely effective in stifling free expression, with targeted individuals censoring themselves, leaving online platforms, and sometimes even leaving their professions altogether.11Julie Posetti and Nabeelah Shabbir, “The Chilling: A Global Study On Online Violence Against Women Journalists,” International Center for Journalists, November 2, 2022, icfj.org/our-work/chilling-global-study-online-violence-against-women-journalists; “Online Harassment Survey: Key Findings,” PEN America, 2017, pen.org/online-harassment-survey-key-findings/; Michelle Ferrier and Nisha Garud-Patkar, “TrollBusters: Fighting Online Harassment of Women Journalists,” Mediating Misogyny (2018): 311-332. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72917-6_16.

Technology companies are backsliding

Social media platforms—such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), and YouTube, where so much of the abuse unfolds—are not doing enough to protect and support their most vulnerable users. In the aforementioned 2021 Pew Research Center study, more than half of Americans saw online harassment as a major problem, yet only 18% felt that social media platforms were doing a good or excellent job of addressing it.12Emily A. Vogel, “The State of Online Harassment,” Pew Research Center, January 13, 2021, pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/americans-views-on-how-online-harassment-should-be-addressed/.

There is a great deal that platforms can do to mitigate online abuse while protecting free expression. They can strengthen harassment, hate speech, and bullying policies by keeping up with ever-evolving tactics.13Platforms use a variety of different terms in their policies—primarily “harassment,” “cyberbullying/ bullying,” and “hateful conduct/hate speech.” In this report, we use the terms “online abuse” and “online harassment,” except in cases where we are discussing a platform’s specific policy, in which case we use the terminology used by that platform in that policy. They can improve the implementation of their policies by bolstering behind-the-scenes content moderation by both human moderators and automated systems, including by creating more flexible and effective harassment reporting processes.14“Shouting into the Void: Why Reporting Abuse to Social Media Platforms is So Hard and How to Fix It,” PEN America, June 29, 2023, pen.org/report/shouting-into-the-void/. They can create proactive tools that shield users from the worst abuse, improve reactive tools that allow users to block, mute, and otherwise take action on abusive content, and introduce more effective accountability tools, such as escalating penalties for repeated policy violations and nudges that prompt users to rethink potentially abusive content before they post.15“No Excuse for Abuse: What Social Media Companies Can Do Now to Combat Online Harassment and Empower Users,” PEN America, March 2021, pen.org/report/no-excuse-for-abuse/.

Over the past decade, many platforms had actually started to reform their policies and add new product features to reduce abuse, albeit only after significant advocacy from affected users and civil society (non-governmental organizations, community groups, and special interest groups). To give just one example, Twitter (now X) only introduced an in-app “report abuse” function in 2013, seven years after the company launched and only after public outcry, including a petition that garnered over a hundred thousand signatures to protest coordinated online attacks against prominent women.16“Twitter Unveils New Tools to Fight Harassment,” CBS News, March 28, 2021, cbsnews.com/video/twitter-unveils-new-tools-to-fight-harassment/; Keith Moore, “Twitter ‘Report Abuse’ Button Calls After Rape Threats,” BBC News, July 27, 2013, bbc.com/news/technology-23477130; Alexander Abad-Santos, “Twitter’s ‘Report Abuse’ Button Is a Good, But Small, First Step,” The Atlantic, July 31, 2013, theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/07/why-twitters-report-abuse-button-good-tiny-first-step/312689/.

Industry incentives for effectively addressing online abuse are mixed. On the one hand, government initiatives to regulate social media platforms are on the rise globally. The EU Digital Services Act (DSA), for example, which was passed in 2022, now requires social media platforms and search engines to “identify, analyse, and assess systemic risks that are linked to their services.”17 “DSA: Very Large Online Platforms and Search Engines,” European Commission, August 25, 2023, digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/dsa-vlops#:~:text=This%20means%20that%20they%20must,consumer%20protection%2 0and%20children’s%20rights. The U.K. Online Safety Act, passed in 2023, establishes a duty of care for online platforms to protect their users from harmful content.18“Online Safety Act: Explainer,” U.K. Department for Science, Innovation & Technology, May 8, 2024, gov.uk/government/publications/online-safety-act-explainer/online-safety-act-explainer. At the same time, because sustaining user attention and maximizing engagement underpins the business model of most social media companies, they build their platforms to prioritize immediacy, emotional impact, and virality, which often serves to amplify abusive behavior.19Amit Goldenberg and James J. Gross, “Digital Emotion Contagion,” Harvard Business School, 2020, hbs.edu/faculty/Publication%20Files/digital_emotion_contagion_8f38bccf-c655-4f3b-a66d-0ac8c09adb2d.pdf; Luke Munn, “Angry By Design: Toxic Communication and Technical Architectures,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7, no. 53 (2020), doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00550-7; Molly Crockett, “How Social Media Amplifies Moral Outrage,” The Eudemonic Project, February 9, 2020, eudemonicproject.org/ideas/how-social-media-amplifies-moral-outrage.

Unfortunately, over the past two years, technology companies have been backsliding, making their priorities abundantly clear. In 2023, among industry-wide layoffs of nearly 200,000 tech-sector employees, platforms significantly or entirely slashed their trust and safety teams, which are primarily responsible for combating online abuse.20“The Crunchbase Tech Layoffs Tracker,” Crunchbase News, news.crunchbase.com/startups/tech-layoffs/; Vittoria Elliot, “Big Tech Ditched Trust and Safety. Now Startups Are Selling It Back As a Service,” WIRED, November 6, 2023, wired.com/story/trust-and-safety-startups-big-tech/. Some platforms have even rolled back, or threatened to remove, vital anti-harassment mechanisms. X, for example, rolled back its deadnaming policy and weakened its block button.21Emma Roth and Kylie Robison, “X will let people you’ve blocked see your posts,” The Verge, September 23, 2024, theverge.com/2024/9/23/24252438/x-blocked-users-view-public-posts; Nora Benavidez, “Big Tech Backslide: How Social Media Rollbacks Endanger Democracy Ahead of the 2024 Elections,” Free Press, December 2023, freepress.net/big-tech-backslide-report; Leanna Garfield and Jenni Olson. “All Social Media Platform Policies Should Recognize Targeted Misgendering and Deadnaming as Hate Speech,” GLAAD, March 5, 2024. glaad.org/social-media-platform-policies-targeted-misgendering-deadnaming-hate-speech/. Meta recently loosened its hate speech policies to allow more abusive content targeting women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and immigrants and significantly scaled back its platform-wide automated moderation systems in favor of user reporting. Experts predict that these changes will increase the proliferation of hate and abuse on Meta’s platforms and put an even greater onus on its users to navigate such content on their own.22Sarah Gilbert, “Three reasons Meta will struggle with community fact-checking,” MIT Technology Review, January 29, 2025, technologyreview.com/2025/01/29/1110630/three-reasons-meta-will-struggle-with-community-fact-checking/; Justine Calma, “Meta is leaving its users to wade through hate and disinformation,” The Verge, January 7, 2025, theverge.com/2025/1/7/24338127/meta-end-fact-checking-misinformation-zuckerberg.

Proactive vs. reactive mechanisms for addressing abuse

Today, platforms are overreliant on features that address online abuse reactively, such as reporting and blocking, which require users to encounter abuse–often repeatedly–in order to mitigate it. The problem is that frequent exposure to online harassment can have serious consequences. A study by UNESCO found that online abuse negatively impacted the mental health of its targets, with 26% of subjects reporting depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other stress-related ailments like sleep loss and chronic pain.23 Julie Posetti, Nabeelah Shabbir et al., “The Chilling: Global Trends in Online Violence Against Women Journalists,” UNESCO, April 2021, 12, unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377223.

In extreme cases, targeted individuals have contemplated and even died by suicide.24 Jackson Richman, “Taylor Lorenz Breaks Down on MSNBC Sharing Experience Being Targeted Online, Contemplated Suicide,” Mediaite, April 1, 2022, mediaite.com/tv/taylor-lorenz-breaks-down-on-msnbc-sharing-experience-being-targeted-online-contemplated-suicide/; Ben Dooley and Hikari Hida, “After Reality Star’s Death, Japan Vows to Rip the Mask Off Online Hate,” The New York Times, June 1, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/06/01/business/hana-kimura-terrace-house.html. The psychological toll has also been shown to cause some public-facing professionals, like journalists, to leave their jobs.25Katherine Goldstein, “When Harassment Drives Women out of Journalism,” International Women’s Media Foundation, 2017, iwmf.org/2017/12/when-harassment-drives-women-out-of-journalism/. It is imperative that technology companies invest in measures that not only address abuse reactively but also reduce users’ exposure to abuse proactively.

Treating online abuse more like spam?

One innovative proposal to proactively reduce exposure to online abuse—explored by technology journalist Sarah Jeong in her 2015 book “The Internet of Garbage”—is to treat it more like spam.26Annalee Newitz, “What if We Treated Online Harassment the Same Way We Treat Spam?” Ars Technica, June 23, 2016, arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2016/06/what-if-we-treated-online-harassment-the-same-way-we-treat-spam/; Sarah Jeong, “The Internet of Garbage,” Forbes, 2015, republished on Vox, 2018, cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12599893/The_Internet_of_Garbage.0.pdf. This idea is inspired by email filters, which have largely been successful in relegating spam to separate folders that users can choose whether or not to interact with. Free expression nonprofit PEN America resurfaced Jeong’s idea in its 2021 report “No Excuse for Abuse,” proposing that platforms give individual users access to a sophisticated mechanism that proactively detects potentially abusive content and quarantines in a centralized area, where users could review the content and decide how to address it—or ignore it altogether.27Viktorya Vilk, Elodie Vialle, and Matt Bailey, “No Excuse for Abuse: What Social Media Companies Can Do Now to Combat Online Harassment and Empower Users,” PEN America, March 31, 2021, pen.org/report/no-excuse-for-abuse/. In order to operate with some degree of automation, such a system would need to be powered, at least in part, by artificial intelligence (AI) and/or large language models (LLMs).28Shagun Jhaver et al., “Designing Word Filter Tools for Creator-led Comment Moderation,” 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, no. 205 (April 2022), 1-21, dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3491102.3517505; Deepak Kumar, Yousef AbuHashem, and Zakir Durumeric, “Watch Your Language: Investigating Content Moderation with Large Language Models,” Human-Computer Interaction (cs.HC), January 2024, arxiv.org/abs/2309.14517.

Most major social media platforms already rely on a combination of automation and human moderation behind the scenes to proactively identify certain kinds of harmful content in order to reduce its reach, label it, hide it behind screens, or delete it altogether—for all users.29Viktorya Vilk, Elodie Vialle, and Matt Bailey, “No Excuse for Abuse: What Social Media Companies Can Do Now to Combat Online Harassment and Empower Users,” PEN America, March 31, 2021, pen.org/report/no-excuse-for-abuse/; email to PEN America from Reddit spokesperson, March 2025; email to PEN America from Meta spokesperson, January 2023. Detecting and adjudicating potentially abusive content at a global scale across hundreds of languages and sociopolitical contexts is inherently challenging and complex. An enormous amount of potentially abusive content is perceptual, contextual, and falls into a gray area, with users disagreeing about whether certain content crosses the line into abuse according to their own individual experience and understanding. Platform-driven moderation systems can and do make mistakes, sometimes failing to protect users from abuse while simultaneously suppressing free expression.

One of the primary benefits of the aforementioned innovative proposal is that it gives individual users access to some of the powerful tools that platforms are already using, thereby giving users more control over the content they see and interact with. Some users may not want to see any potentially abusive content at all, while others may, for example, need to sift through banal personal attacks in order to track credible death threats. The point, however, is that users themselves should be able to exercise significantly more agency over their own social media experience.

What you will find in this report

In this report, PEN America has joined forces with Consumer Reports, the nonprofit research, testing and advocacy organization, to explore in greater depth what would happen if technology companies treated online abuse more like spam. Like Jeong, we use the comparison with spam not literally, but as metaphor for the idea of platforms giving individual users more robust automated mechanisms to proactively detect potentially abusive content and quarantine it, so that users could choose whether to review, address it, or ignore it. In Section I, we map out how a mechanism like this could work. In Sections II and III, we explore whether the technology to automatically detect abusive content currently exists, analyzing in-platform and third-party tools that already perform some of these functions and examining how this landscape is evolving with the advent of LLMs and generative AI (GenAI) technologies. In Section IV, we examine why users do not already have access to more robust mechanisms to proactively detect and isolate abusive content, including platform incentive structures and priorities. In Section V, we discuss the challenges of proactively detecting and quarantining abusive content, from implicit bias to explicit censorship, and map out ways these challenges can be addressed. In Sections VI and VII, we end with an exploration of the advantages of treating online abuse more like spam and provide a detailed set of recommendations outlining how technology companies can put such proactive anti-abuse measures into practice.

We intend this report to guide technologists, policy experts, trust and safety experts, and researchers in the technology, civil society, and academic sectors who are looking for solutions to better protect and support people facing online abuse. It is important to note that we intend this proposal to be one intervention among many that platforms deploy to reduce online harassment and hate. A user-driven mechanism like the one that we propose here cannot—and should not—replace platform-driven content moderation. This would unduly place the onus on individual users, instead of on well-resourced and powerful platforms and their own internal content moderation teams. We need both individualized tools that allow users to shape their online experiences and rigorous platform-driven content moderation efforts to ensure that online spaces are truly safe, equitable, and free.

Section I: Taking Inspiration From Spam to Reduce Exposure to Online Abuse

In the early days of email in the 1990s, people were bombarded with spam. Within a decade, all major email providers had integrated spam filters that automatically identified junk mail and isolated it in designated spam folders to keep it from cluttering inboxes.30Lindsay Tjepkama, “A (Brief) History of Spam Filtering and Deliverability,” Emarsys, December 19, 2013, emarsys.com/learn/blog/a-brief-history-of-spam-filtering-and-deliverability-gunter-haselberger/#:~:text=The%20late%201990s% 20%2F%20early%202000s,keywords%2C%20patterns%20or%20special%20characters.

With the advent of social media, spam detection was also integrated into platforms to reduce the visibility of junk in feeds, direct messages (DMs), etc. Although there are key differences that make filtering online abuse significantly more difficult than filtering spam—which we explore in detail in Section V—lessons could be learned from the world of spam, where automated filtering has largely been a success.

In its 2021 report “No Excuse for Abuse,” PEN America—building on an idea sketched out in technology journalist Sarah Jeong’s 2015 book “The Internet of Garbage”—recommended a mechanism that would “proactively filter abusive content (across feeds, threads, comments, replies, direct messages, etc.) and quarantine it in a dashboard, where [users could] review and address [the content] as needed with the help of trusted allies.”31Viktorya Vilk, Elodie Vialle, and Matt Bailey, “No Excuse for Abuse: What Social Media Companies Can Do Now to Combat Online Harassment and Empower Users,” PEN America, March 31, 2021, pen.org/report/no-excuse-for-abuse/. In other words, technology companies could take inspiration from email spam folders to reduce individual users’ exposure to hate and harassment on social media platforms, in email, and beyond. Below we outline how such a mechanism could work in three phases—detection, review, and action—and offer more detailed recommendations in Section VII.

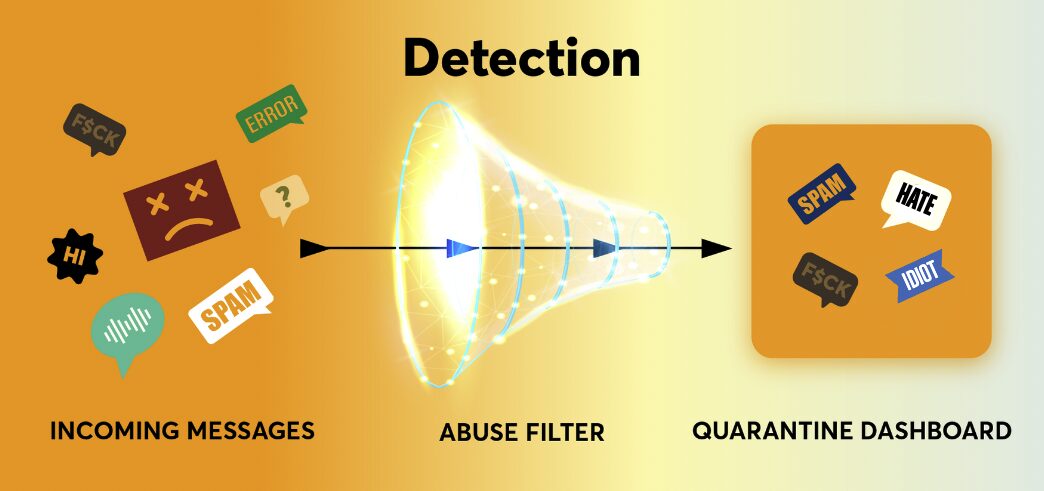

Detection

In the detection phase, a filter automatically reviews incoming content, identifies potential abuse, and determines whether such content should be made visible to the impacted user (via their regular feeds, channels, etc.) or hidden from the impacted user and sent to a user-accessible quarantine area instead. The crux of this step is how automated filtering would work, which could rely on anything from user-created word filters and community-driven models to personalized, machine learning solutions. We detail what kinds of automated filtering are currently technically feasible, as well as their advantages and challenges, in Section V.

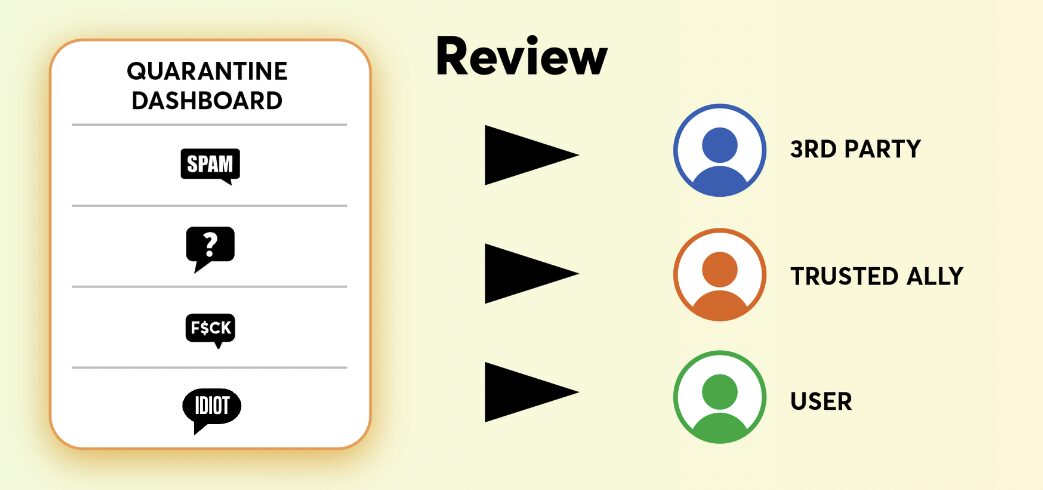

Review

In the review phase, content that has been filtered into the quarantined area is organized into a centralized user-facing interface, such as a dashboard. The user can then choose to review all quarantined content in the dashboard and decide what to do with it. In this dashboard, users could also have the option to blur quarantined content by default so that they are not immediately confronted with abuse, but instead opt into seeing it. To further reduce the psychological toll, users could be given the option to “friendsource” the quarantined content by delegating access to their dashboard to a friend or other trusted third party, such as an employer or civil society organization, who could help review and take action.32Kaitlin Mahar, Amy X. Zhang, and David Karger, “Squadbox: A Tool to Combat Email Harassment Using Friendsourced Moderation,” 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, no. 586 (April 2018), 1-13, homes.cs.washington.edu/~axz/squadbox.html.

Action

In the action phase, the user or their trusted allies could address the abusive content, including marking the content as not abusive to remove it from quarantine and ensure it appears on their feed, timeline, DMs, etc.; reporting the content if it violates platform policies; blocking or muting the accounts behind the abusive content; or otherwise leveraging in-platform features to address it. Even if the user does not take explicit action on the abusive content quarantined in their dashboard, that content has automatically been detected and documented, which is a critical step in enabling targets of abuse to protect themselves and exert agency over their experiences.

To be clear, with this proposed mechanism, potentially abusive content that has been automatically detected and quarantined does not automatically disappear from view for all users of the platform; it is hidden only from the targeted user’s view via their main feeds, DMs, channels, etc. The targeted user can access all quarantined content at any time, via their dashboard, and remove it from quarantine or otherwise address it as needed.

Section II: Does the Technology to Automatically Detect Online Abuse Currently Exist?

In order to detect spam, abuse, and other forms of harmful content, technology companies rely on a combination of human and automated review and moderation. For automation, platforms rely on AI technologies. AI, in the words of John McCarthy, who coined the term, is “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines, especially intelligent computer programs”33John McCarthy, “What Is Artificial Intelligence?” Stanford University Department of Computer Science, November 12, 2007, formal.stanford.edu/jmc/whatisai.pdf.—making computer systems that are able to perform tasks commonly associated with human intelligence. Most automated detection systems today that analyze text-based content (whether spam or abuse) rely on some form of Natural Language Processing (NLP)—a specific branch of AI that primarily focuses on giving computers the ability to process and take action on human language.

AI is not new, and neither is NLP. Theoretical interest in AI and NLP emerged in the 1940s and 1950s, and the technologies behind AI and NLP, like deep learning, have existed for a decade.34Gil Press, “A Very Short History of Artificial Intelligence (AI),” Forbes, December 30, 2016, forbes.com/sites/gilpress/2016/12/30/a-very-short-history-of-artificial-intelligence-ai/; “Natural Language Processing,” Stanford University, 2004, cs.stanford.edu/people/eroberts/courses/soco/projects/2004-05/nlp/overview_history.html; Keith D. Foote, “A Brief History of Deep Learning,” DATAVERSITY, February 4, 2022, dataversity.net/brief-history-deep-learning/. Social media companies are already deploying a range of these technologies to automatically detect harmful content, including online abuse, on their platforms—and have done so for years.35Rem Darbinyan, “The Growing Role of AI in Content Moderation,” Forbes, June 14, 2022, forbes.com/councils/forbestechcouncil/2022/06/14/the-growing-role-of-ai-in-content-moderation/; email to PEN America from Reddit spokesperson, March 2025; email to PEN America from Meta spokesperson, January 2023.

Most automated detection technologies are used to facilitate content moderation behind the scenes. The automated detection technology is controlled by employees of platforms or third-party companies rather than being made available to individual users.

Technology companies have gradually integrated features that leverage automated detection to give users more control over their individual experiences. Most social media companies now allow users to manually hide or mute certain kinds of content that they do not want to see in their own feeds, DMs, comments, etc.—though each platform’s features are distinct in their functionality and terminology. On most platforms, users can manually set keywords so that responses to their content containing those keywords are automatically concealed under a “hidden replies” cover, which other users then need to click through to reveal the response. This is distinct from allowing users to delete responses to their own content altogether, which makes the content invisible for all users.36Kaya Yurieff, “Twitter Now Lets Users Hide Replies to Their Tweets,” CNN, November 21, 2019, cnn.com/2019/11/21/tech/twitter-hide-replies/index.html. A few platforms have also given users access to a handful of preset filters that reduce the visibility of sensitive or otherwise harmful content. Below we map out the relevant features we could find across multiple major social media platforms:

X (formerly Twitter) allows users to manually mute entire accounts, individual posts, and replies to their posts. Users can also manually mute content by keyword, emoji, or hashtag. They cannot mute DMs, but they can hide DM notifications.37“How to mute accounts on X,” X, accessed March 10, 2025, help.x.com/en/using-x/x-mute; “How to Use Advanced Muting Options,” X, accessed March 10, 2025, help.x.com/en/using-x/advanced-x-mute-options. In terms of automated filters set by the platform (rather than manual filters set by users), Twitter (now X) introduced a “quality filter” in 2016, which automatically removes “lower-quality content” (e.g., duplicate posts) from users’ notifications.38“About the Notifications Timeline,” X, accessed August 7, 2024, help.x.com/en/managing-your-account/understanding-the-notifications-timeline; Michael Burgess, “Twitter Introduces ‘Quality Filter’ to Tackle Harassment, ” WIRED, August 19, 2016, wired.com/story/twitter-quality-filter-turn-on.

Facebook offers no exact equivalent to X’s (formerly Twitter’s) manual muting features, but users can “snooze” accounts or groups for 30 days, mute other users’ stories, and permanently unfollow posts without unfriending accounts.39 “How Do I Unfollow a Person, Page, or Group on Facebook,” Facebook, accessed July 18, 2024, facebook.com/help/190078864497547; “Mute or Unmute a Story on Facebook,” Facebook, accessed July 18, 2024, facebook.com/help/408677896295618. Users can also select keywords to be blocked from appearing in comments on their profiles.40Email to PEN America from Meta spokesperson, January 2023. From the standpoint of automated filters set by the platform (rather than manual filters set by users), Facebook allows users to “filter for profanity,” but again only on pages and profiles set to Professional Mode rather than for all users.41“Manage Comments with Moderation Assist for Pages and Professional Mode,” Facebook, accessed August 12, 2024, facebook.com/help/1011133123133742; “Turn Comment Ranking On or Off for YourFacebook Page,” Facebook, accessed July 18, 2024, facebook.com/help/1494019237530934.

Instagram, unlike Facebook and X, automatically detects and then hides comments containing offensive words, phrases, and emojis by default, and users have the option to click to reveal the hidden content. Users can manually add additional words or phrases using the “hidden words” feature.42“Hide Comments or Message Requests You Don’t Want to See on Instagram,” Instagram, accessed June 24, 2024, help.instagram.com/700284123459336; Email to PEN America from Meta spokesperson, January 2023. Instagram also enables users to manually mute posts or stories and to mute accounts.43 “Mute or Unmute Someone on Instagram,” Instagram, accessed July 18, 2024, help.instagram.com/469042960409432. In terms of platform-set automated filters (rather than user-set manual ones), users can turn on “advanced comment filtering,” which will detect and filter additional comments that meet Instagram’s criteria for potentially objectionable content.44“Hide Comment or Message Requests You Don’t Want to See on Instagram,” Instagram, accessed August 2, 2024, help.instagram.com/700284123459336. Instagram also introduced a feature called “limits interactions,” initially only for influencers, in 2021. Limit interactions allows influencers to automatically limit interactions from recent followers, everyone except close friends, or all users to prevent unwanted accounts from responding to their stories, tagging or mentioning them, commenting on their posts, and remixing their content; in 2024, they made this feature available to all users.45“Temporarily Limit People From Interacting with You on Instagram,” Instagram, accessed August 7, 2024, help.instagram.com/4106887762741654/?helpref=uf_share.

TikTok does not automatically filter or hide abusive content by default. Instead, users can opt into several automated filtering modes: restricted mode, which hides “mature and complex” content, and comment care mode, which hides comments from strangers (people who neither follow a user or are followed by them) and comments that are similar to others that a user has previously disliked, reported, or deleted.46“Countering Hate Speech and Behavior,” TikTok, accessed June 25, 2024, tiktok.com/safety/en/countering-hate; “Comment Care Mode,” TikTok, accessed August 19, 2024, support.tiktok.com/en/safety-hc/account-and-user-safety/comment-care-mode. Users can manually add keyword filters, which automatically detect and hide comments with the keyword(s). Users can also opt in to automatically hiding all comments and then manually approving each comment to make it visible.47 “Countering Hate Speech and Behavior,” TikTok, accessed June 25, 2024, tiktok.com/safety/en/countering-hate.

The in-platform features outlined above go some way toward enabling users to approach abusive content more like spam, in that users can leverage automated detection technologies to reduce their own exposure. However, there are some important differences in what we are proposing. Currently, to automatically filter content for their own accounts, users often have to choose between hiding/muting content manually or switching on preset filters. In-platform features that allow users to manually set their own keywords, emojis, hashtags, etc., offer more transparency and control but are also more labor-intensive. Most preset filters, on the other hand, are binary and a black box; users can turn the feature either on or off, but they cannot fine-tune it or easily see everything that has been filtered out.48Leigh Honeywell, interview by Yael Grauer, Consumer Reports, December 9, 2021. All of these features are piecemeal, idiosyncratic, and spread out across multiple different sections of platform apps and websites.

In recent years, several social media companies have been experimenting with significantly more robust, flexible, and transparent mechanisms that allow users to automatically detect and filter out abusive content, which we outline below:

Facebook’s Moderation Assist: In 2021, Meta piloted the new Moderation Assist feature on specific parts of Facebook.49Leah Loeb, “Facebook Introduces Comment Moderation and Live Chat for Creators,” Hootsuite, December 10, 2021, blog.hootsuite.com/social-media-updates/facebook/facebook-comment-moderation-live-chat-for-creators/. Page admins or those with profiles in Professional Mode can manually fine-tune a range of criteria to detect and filter out certain content (e.g., if the comment contains a given keyword, or if the commenter doesn’t have any friends or followers).50 “Manage Comments with Moderation Assist for Pages and Professional Mode,” Facebook, accessed June 24, 2024, facebook.com/help/1011133123133742. Those who use Moderation Assist have access to a Professional Dashboard, where they can review hidden comments and decide how to address them, as well as access their moderation activity log. At present, the Moderation Assist feature is not available to every user on the platform.51“Manage Comments with Moderation Assist for Pages and Professional Mode,” Facebook, accessed June 24, 2024, facebook.com/help/1011133123133742; email to PEN America from Meta spokesperson, January 2023.

YouTube’s Channel Comments and Mentions: Since at least 2020, YouTube has allowed users who post videos to review and moderate every comment made in reply to their videos or on their channel. Users choose their own criteria to automatically detect comments and hold them for review before publication. Users can choose to not hold any comments for review, hold “potentially inappropriate comments,” hold a broader range of “potentially inappropriate comments,” or hold all comments.52“Learn About Comment Settings,” YouTube Help, accessed July 23, 2024, support.google.com/youtube/answer/9483359?hl=en#zippy=%2Con; Jordan, “Potentially inappropriate comments now automatically held for creators to review,” YouTube Help, accessed July 23, 2024, support.google.com/youtube/thread/8830320/potentially-inappropriate-comments-now-automatically-held-for-creators-to-review?hl=en.

All incoming comments are then automatically analyzed according to users’ settings and divided into two folders. In one folder are comments that the platform has deemed acceptable and automatically published. In the second folder are comments that the platform has held for review, which the user then manually approves or rejects for publication. This system automatically detects potentially harassing or otherwise unwanted comments, and the user can adjust, to some degree, the strictness of the filter.53“Review and Reply to Comments,” YouTube Studio App Help Centre, accessed June 18, 2024, support.google.com/youtubecreatorstudio/answer/9482367?hl=en-IN&co=GENIE.Platform%3DDesktop#:~:text=Check%20com ments%20on%20your%20videos%20and%20channel&text=From%20the%20left%20menu%2C%20select,by%20YouTube%20a s%20likely%20spam.

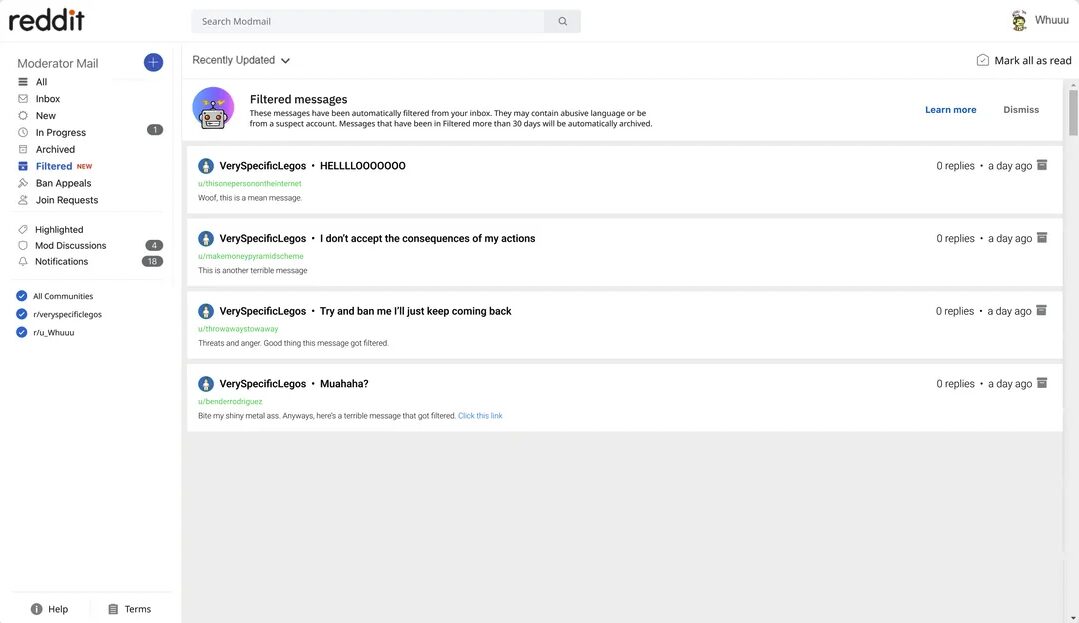

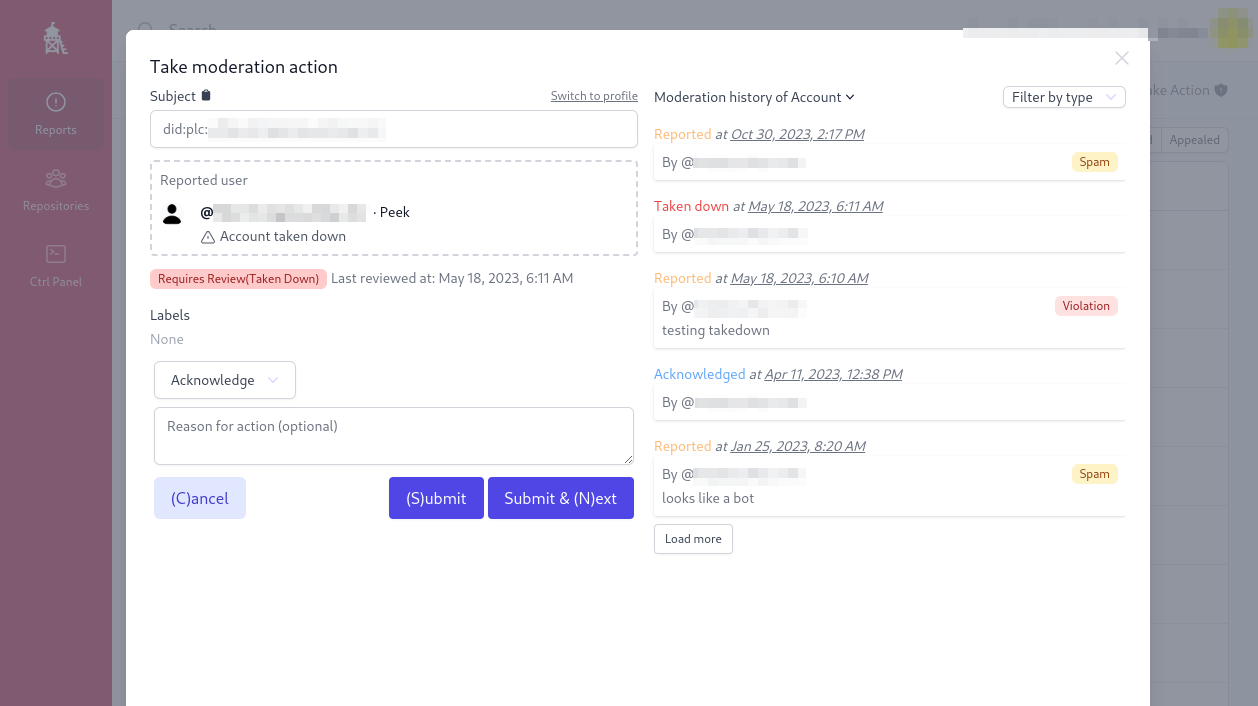

Reddit’s Harassment Filter and Modmail Folder: Reddit offers multiple automated harassment detection tools—several specifically to subreddit moderators, rather than to all users.54Chase DiBenedetto, “Reddit Introduces an AI-powered Tool That Will Detect Online Harassment,” Mashable, March 7, 2024, mashable.com/article/reddit-ai-harassment-filter; email to PEN America from Reddit spokesperson, March 2025. The Harassment Filter automatically detects content that is likely to be considered harassing under the platform’s policies. Moderators can then review the flagged content and either approve it to be posted to the community thread or remove it. Moderators are able to refine the Harassment Filter by toggling between filtering fewer comments with more accuracy or filtering more comments with less accuracy. For additional fine-tuning, moderators can also manually add up to 15 keywords that the algorithm will not filter out.55“Harassment Filter,” Reddit, accessed June 25, 2024, support.reddithelp.com/hc/en-us/articles/238562096 38932-Harassment-filter. In addition, Reddit also offers moderators the Modmail Folder. This feature automatically redirects potentially harassing modmail from a moderator’s general inbox to a filtered folder. The Modmail Folder was designed to give moderators greater control over when they view and interact with potentially abusive content. Additionally, they can manually report harassing modmail messages missed by the filter and move into the regular inbox any non-harassing modmail messages that have been erroneously filtered out.56“Modmail Folders,” Reddit, accessed June 25, 2024, support.reddithelp.com/hc/en-us/articles/15484158762260- Modmail-folders#h_01G8YBFB9VYVREXYWH1SCDP141; email to PEN America from Reddit spokesperson, March 2025.

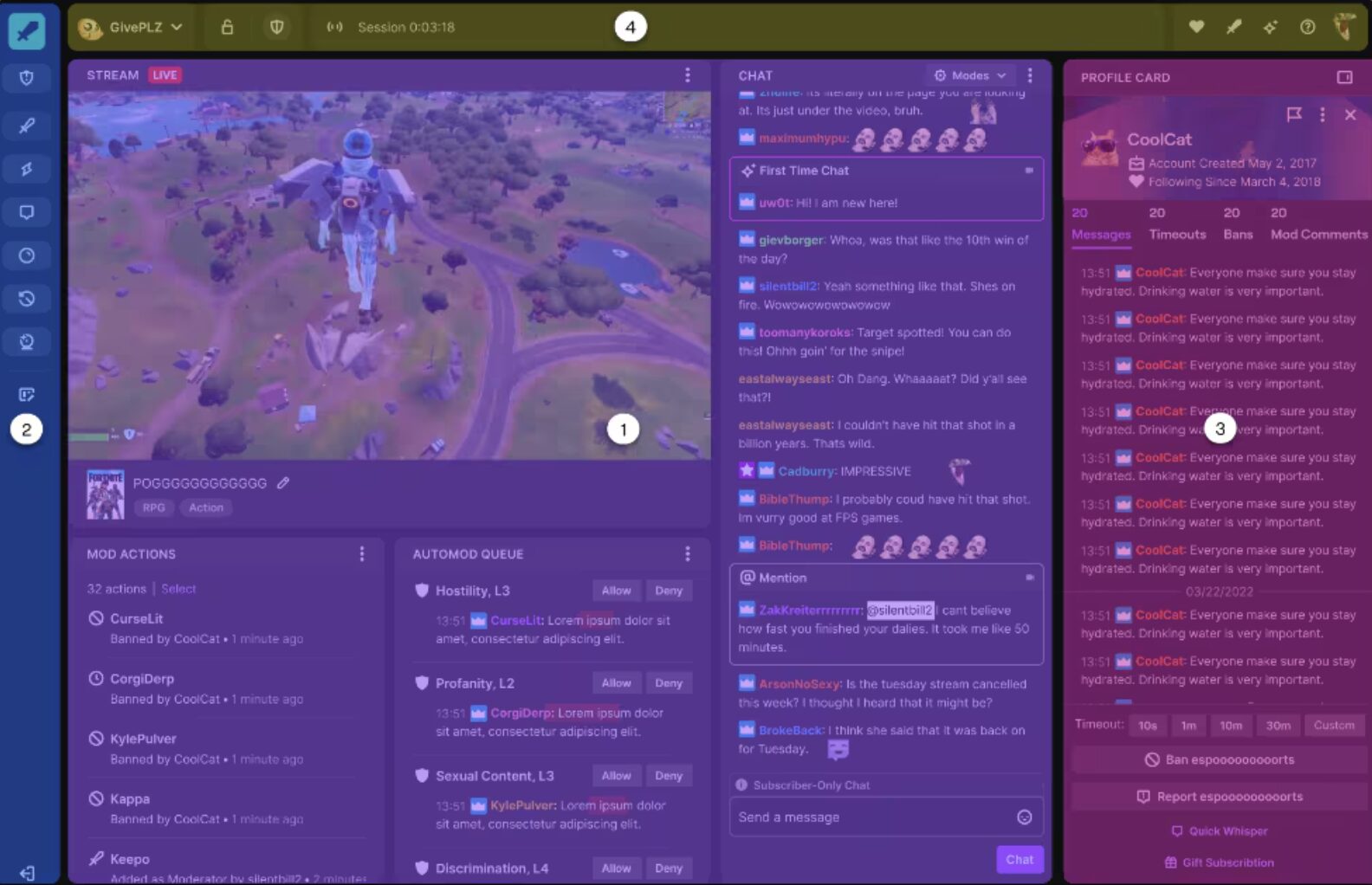

Twitch: Since 2016, Twitch has offered a feature called AutoMod, which uses AI and NLP to flag and quarantine potentially offensive or abusive content shared on livestream chats.57Andrew Webster, “Twitch introduces a new automated moderation tool to make chat friendlier,” The Verge, December 12, 2016, theverge.com/2016/12/12/13918712/twitch-automod-machine-learning-moderation-tool. Streamers can customize the sensitivity of AutoMod across four levels of severity: Level One, for example, only filters out discrimination, whereas Level Four addresses discrimination, sexual content, profanity, and most forms of hostility.58“How to Use AutoMod,” Twitch, accessed February 24, 2025, help.twitch.tv/s/article/how-to-use-automod?language=en_US.

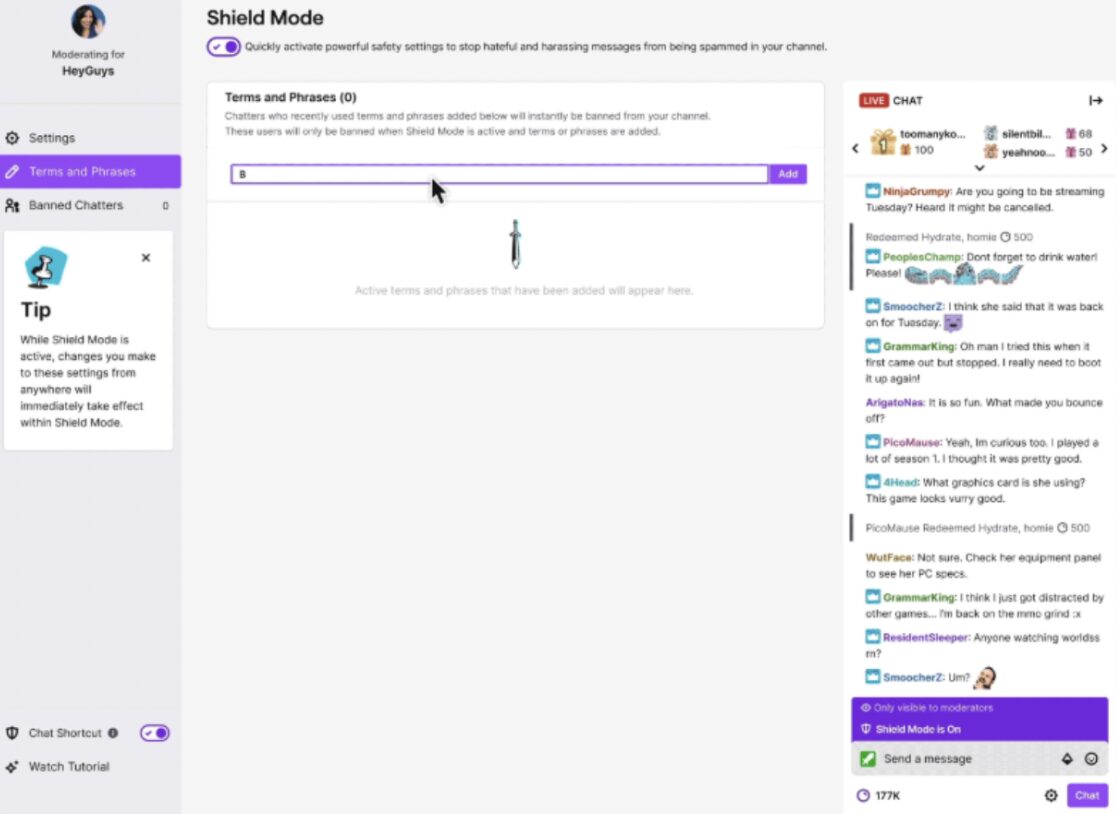

Streamers can then review the quarantined content, and decide to allow or prevent the message to be posted to the public chat. The platform also offers Friendsourcing, where streamers call on friends or fans to help moderate their chats through AutoMod.59Nicole Carpenter, “Moderators are the unpaid backbone of Twitch,” Polygon, October 20, 2023, polygon.com/23922227/twitch-moderators-unpaid-labor-twitchcon-2023. Streamers can deploy AutoMod in conjunction with other moderation features through Shield Mode, which allows streamers to build a custom set of moderation tools under one centralized shield that can easily be toggled on and off as needed.60“Protect Your Channel With Shield Mode,” Twitch, November 30, 2022, safety.twitch.tv/s/article/Protect-your-channel-with-Shield-Mode?language=en_US; email to PEN America from Twitch spokesperson, March 2025.

Bluesky, which launched as an independent entity in 2021, was built from its inception to enable a “stackable” approach to moderation. This means that the platform not only makes use of its own internal moderation teams but also supports the integration of third-party moderation for users. In other words, users who want additional protection from potentially abusive content can set up additional moderation services on top of what Bluesky already offers. Bluesky open-sourced Ozone, its internal moderation tool, in March 2024. This allows individuals and/or teams to set up their own specific preferences to label, triage, and escalate potentially abusive content. Furthermore, Ozone can operate not just on Bluesky but also on any platform that uses the AT Protocol, a communication standard that enables the creation of decentralized social networking platforms; in other words, a user could set up Ozone on Bluesky and then use it across other decentralized platforms.61The Bluesky Team, “Bluesky’s Stackable Approach to Moderation,” Bluesky, March 12, 2024, bsky.social/about/blog/03-12-2024-stackable-moderation; Richard Ernszt, “What is AT Protocol (Authenticated Transfer Protocol)?” Comparitech, November 25, 2024, comparitech.com/blog/vpn-privacy/what-is-at-protocol/.

These newer mechanisms demonstrate that platforms can, in fact, automatically detect and quarantine abusive content. By empowering users to fine-tune how strictly they want to filter content, Bluesky, Twitch, and Reddit’s features provide particularly helpful models. According to Reddit, takeup rate for and satisfaction with both the Harassment Filter and Modmail Filter are very high among community moderators.62 In a March 2025 email to PEN America, a Reddit spokesperson reported that 72% of the largest Reddit communities have adopted the Harassment Filter, and 95% have adopted the Modmail Filter, and both have received generally positive feedback from moderators. Many moderators highlight that the filters surface inappropriate content that may otherwise go unnoticed, which helps keep communities safer without increasing the time or energy spent on moderation. Twitch has reported similarly high adoption and approval ratings of AutoMod and Shield Mode.63 In an email to PEN America, a Twitch spokesperson reported that 80% of channels use AutoMod and Shield Mode, up from 20% in 2022. Bluesky also serves as a useful model because it was set up from the get-go to enable a mix of both internal features and third-party moderation to reduce online abuse.64The Bluesky Team, “The AT Protocol,” Bluesky, October 18, 2022, bsky.social/about/blog/10-18-2022-the-at-protocol. That said, the existing features on most major social media platforms do not provide such flexible and accessible solutions. Only a limited subset of YouTube and Reddit users, for example, can leverage the kinds of fine-tuning features that we advocate for here, and neither platform offers a centralized dashboard in which any individual user can review all of the different types of content that has been filtered out on that user’s account across all of the different parts of the platform (including comments, replies, tags, and DMs).

Because no social media company (or email provider, for that matter) has yet integrated a sufficiently robust, comprehensive, user-friendly mechanism to detect and quarantine abusive content that is available to all users, third-party technology companies have stepped up. These tools have different functions and strengths in allowing individual users to limit their exposure to harassment, but none yet offers the full range of protections we envision.

Block Party: In 2021, software engineer and entrepreneur Tracy Chou launched a third-party application that users could plug into Twitter (now X) to reduce exposure to abusive content. Block Party automatically detected abusive content via heuristics rather than machine learning (by, for example, restricting mentions from strangers) and quarantined it into “lockout folders” for later review.65Tracy Chou, “Meet the App Developer Creating a Simple Tool That Could Slay All Online Trolls,” BBC Science Focus Magazine, June 19, 2021, sciencefocus.com/future-technology/bullying-how-to-slay-the-social-media-trolls. Higher tiers of Block Party also gave users the ability to assign helpers to assist with monitoring, muting, or blocking abuse.66Block Party, blockpartyapp.com/; “Product FAQ,” Block Party, accessed August 12, 2024, blockpartyapp.com/faq/#what-does-a-helper-do. Unfortunately, this specific Block Party tool is no longer available due to X’s ongoing changes to Application Programming Interface (API) access and pricing. Instead, Block Party has pivoted to empowering users to tighten their privacy and safety settings across multiple major social media platforms.67Sara Keenan, “Privacy Party Is Block Party’s Bold Response To Twitter’s API Changes: The New Haven For Online Privacy,” People of Color in Tech, March 12, 2024, peopleofcolorintech.com/articles/privacy-party-is-block-partys-bold-response-to-twitters-api-changes-the-new-haven-for-online privacy/.

Squadbox: In 2018, MIT’s Computer Science and AI Laboratory piloted a thirty-party application that users could plug into their email account to reduce exposure to abusive emails. The platform enabled Friendsourcing: A user could designate a “squad” of supporters to review and manage hateful or harassing email content on their behalf.68“Squadbox Team,” Squadbox, accessed September 3, 2024, squadbox-dev.csail.mit.edu/#team. All emails, aside from those sent by verified contacts, were automatically forwarded to squad supporters who could either quarantine messages or forward them to the targeted individual.69Katilin Mahar, Amy X. Zhang, David Karger, “Squadbox: A Tool to Combat Email Harassment Using Friendsourced Moderation,” CHI 2018: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, no. 586 (April 21, 2018): 1-13, doi/10.1145/3173574.3174160. The tool is currently in a redevelopment and testing phase.

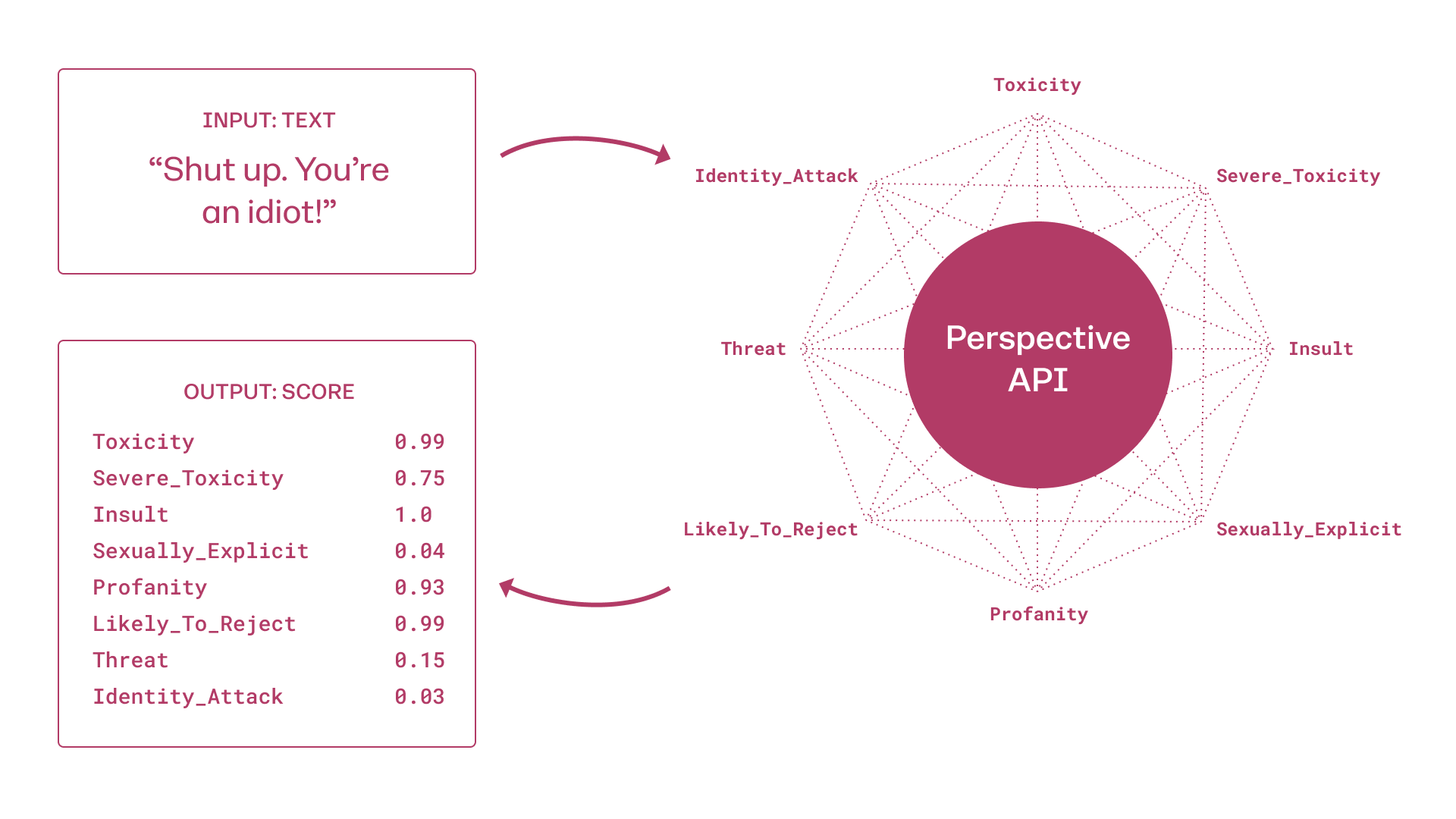

Perspective API: Launched by Google’s Jigsaw and Counter Abuse Technology teams in 2017, Perspective API is a free and open-source Application Programming Interface (API), which software developers can use to build a tool. It is designed for communications-focused companies, such as media organizations, rather than for individual users. Perspective API can be integrated into the backends of these companies’ websites to provide their human moderators with support to more effectively moderate comments and/or to encourage individual users to reconsider posting “toxic” comments.70“About the API FAQs,” Perspective, accessed September 3, 2024, support.perspectiveapi.com/s/about-the-api-faqs?language=en_US. When it launched in 2017, Perspective API used machine learning to automatically detect toxic content, which Jigsaw defined as a “rude, disrespectful, or unreasonable comment that is likely to make someone leave a discussion.”71“How It Works,” Perspective, accessed September 3, 2024, perspectiveapi.com/how-it-works/. According to a Jigsaw spokesperson, the newest iterations of Perspective API leverage AI to power the integration of customizable attributes that help community managers configure their own detection rules based on their own norms and guidelines.72Email to PEN America from Google/Jigsaw spokesperson, March 2025.

TRFilter: In 2022, the Thomson Reuters Foundation launched TRFilter based on an open source tool built by Google’s Jigsaw team called Harassment Manager, which uses Perspective API to help users to automatically detect and document the harassment they received online, built initially for Twitter (now X).73“Thomson Reuters Foundation Launches New Tool to Protect Journalists Against Online Violence,” Trust.org, June 30, 2022, accessed September 4, 2024, trust.org/i/?id=097399b5-492a-4587-89d2-d94d0a0eb259. This tool enabled journalists to automatically detect and document abusive content on Twitter (now X), as well as to automatically mute, block, and save comments en masse—with light touch manual review—and to hide abusive content to avoid exposure.74Marina Adami and Eduardo Suárez, “Many Journalists Come Under Attack: TRF Launches Free Tool to Monitor Online Abuse,” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, July 19, 2022, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/news/many-journalists-come-under-attack-trf-launches-free-tool-monitor-online-abuse. Similar to Block Party, TRFilter can no longer function as designed due to X’s changes to API access and pricing.75David Cohen, “Thomson Reuters Foundation, Google’s Jigsaw, Twitter Take Steps to Protect Journalists,” Adweek, June 30, 2022, adweek.com/media/thomson-reuters-foundation-googles-jigsaw-twitter-take-steps-to-protect-journalists/; Ester Sun, “Digital Tool Helps Shield Journalists from Online Violence,” Voice of America, July 15, 2022, voanews.com/a/digital-tool-helps-shield-journalists-from-online-violence/6660881.html.

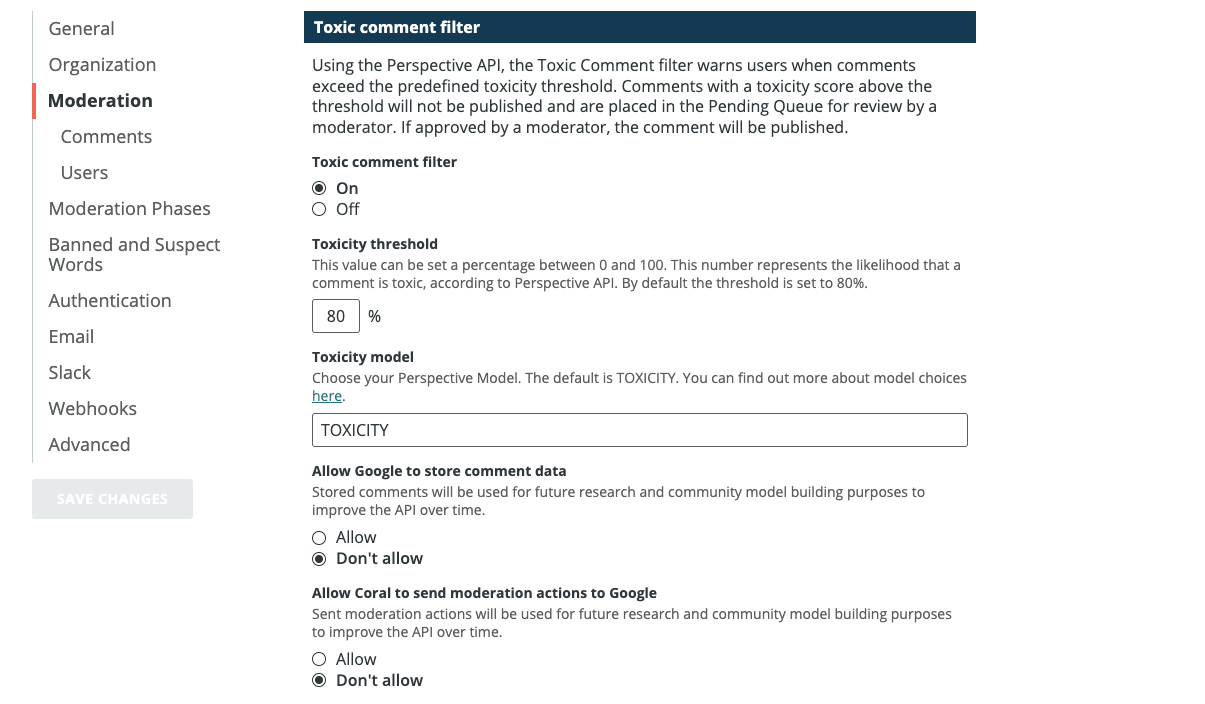

Coral: Coral was initially launched in 2014 as The Coral Project by the Mozilla Foundation, in collaboration with the Knight Foundation, The New York Times, and The Washington Post, and it is now part of Vox Media. Coral is a commenting platform designed for media organizations (rather than individual users) to publish and moderate comments, reviews, and Q&As on their websites and apps.76“The Coral Project Is Moving to Vox Media,” Mozilla Blog, January 22, 2019, blog.mozilla.org/en/mozilla/the-coral-project-is-moving-to-vox-media/#:~:text=Since%202015%2C%20the%20Mozilla%20Fou ndation,%2Dcentered%2C%20open%20source%20software. Coral uses many different types of computer intelligence to help with moderation, and offers easy integrations with third-party AI software; one example of this is Coral’s optional integration with Perspective API (described above) to calculate a “Toxicity Threshold” that organizations can use to identify and remove abusive comments.77“Toxic Comments,” The Coral Project, accessed September 4, 2024, legacy.docs.coralproject.net/talk/toxic-comments/. While Coral does leverage AI to facilitate automated detection, the tool was always built with the intention of keeping humans in the loop: “We do AI-assisted human moderation,” says Andrew Losowsky, who oversees the Coral platform. “Humans are ultimately the main moderators.”78 Andrew Losowsky, interview by Yael Grauer, Consumer Reports, and Viktorya Vilk, PEN America, January 5, 2022.

While each of these third-party tools approximate the idea of treating online abuse like spam, none do exactly what we propose. Two of them, Perspective API and Coral, are built for use by organizations rather than individuals. Of the three built for individual use—Block Party, Squadbox, and TRFilter—none are currently operational as originally intended.

What we propose is that platforms integrate a mechanism that combines aspects of all of the in-platform features and third-party tools described above in order to provide users with greater control over the content they see. Platforms can build this mechanism themselves or they can ensure free and open access to their API so that third-party companies can build such a mechanism; what is important, however, is that the mechanism be secure and directly and smoothly integrated into the platform’s primary user experience. We offer detailed recommendations for how to build such a mechanism in Section VII. New technologies like large language models (LLMs) and generative AI (GenAI) are a significant advancement in the field of NLP and could be further harnessed to improve automated abuse detection, which we explore in the next section.

Section III: What Role Can LLMs and GenAI Play?

LLMs and GenAI—two relatively new technologies that exploded in popularity since the release of ChatGPT in November 2022—represent a significant advancement in the capabilities of AI to analyze existing content and to generate new content.79Bernard Marr, “A Short History Of ChatGPT: How We Got To Where We Are Today,” Forbes, May 19, 2023, forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2023/05/19/a-short-history-of-chatgpt-how-we-got-to-where-we-are-today/. It is therefore important to consider how these technologies may impact both the prevalence of online abuse and its detection.

LLMs are the most current version of NLP systems that can effectively analyze and generate human language text. At a high level, the way LLMs work is by scanning enormous amounts of available text, usually from across the web—including news articles and social media—and using that data to train the algorithms that power the model. The model can then, when fed new information, analyze text, make predictions, or even generate new text. LLMs excel at pattern recognition and are rapidly becoming more sophisticated, powering chatbots like ChatGPT.80“What are Large Language Models (LLMs)?” IBM, accessed September 11, 2024, ibm.com/topics/large-language-models.

Unlike traditional AI systems that are designed to recognize patterns and make predictions, GenAI can generate new content in response to prompts—in the form of text, images, audio, videos, computer code, and beyond. Like LLMs, GenAI relies on models trained on enormous amounts of data, mostly from the web.81Nick Routley, “What is generative AI? An AI explains,” World Economic Forum, February 6, 2023, weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/generative-ai-explain-algorithms-work/.

Over the past two years, GenAI has become significantly more convincing, affordable, and accessible, powering systems like DALL-E.

In PEN America’s 2023 report, “Speech in the Machine,” the authors took the view that AI technologies are not inherently good or bad for free expression, but that “what matters is who uses them, how they are being used, and what stakeholders can do to shape a future in which new technologies support and enhance fundamental rights.” This includes the social media sphere. On the one hand, LLMs and GenAI can be harnessed to supercharge disinformation and online abuse campaigns because they can generate more text, audio, and video content that looks and sounds more convincingly human, in more languages, faster. On the other hand, these technologies can also be used to facilitate the detection of abusive or otherwise harmful content in order to more effectively and efficiently address it.82Summer Lopez, “Speech in the Machine: Generative AI’s Implications for Free Expression,” PEN America, July 21, 2023, pen.org/report/speech-in-the-machine/.

Researchers have started exploring how LLMs and GenAI could help proactively detect harmful content. Recent research from Stanford University, UC San Diego, and the University of Buffalo demonstrated that LLMs can achieve significantly better accuracy in automatically detecting abusive content online than state-of-the-art non-LLM models, especially in the context of Standard American English.83Deepak Kumar, Yousef AbuHashem, Zakir Durumeric, “Watch Your Language: Investigating Content Moderation with Large Language Models,” ArXiv, September 25, 2023, arxiv.org/pdf/2309.14517; Kenyan Guo et al., “An Investigation of Large Language Models for Real-World Hate Speech Detection,” ArXiv, January 7, 2024, arxiv.org/pdf/2401.03346. The model performed better at automatically detecting content that violates platform policies when it was provided with the full context of a conversation, which represents a significant step forward. This early research suggests that automated systems to detect abuse might soon benefit from LLMs in specific contexts. In fact, Reddit has already incorporated LLMs into its Harassment Filter for moderators (for more, see Section II), and a handful of moderators are already reporting improved performance for specific categories of harm.84“Harassment Filter,” Reddit, support.reddithelp.com/hc/en-us/articles/23856209638932-Harassment-Filter; email to PEN America from Reddit spokesperson, March 2025.

Nevertheless, LLMs still have significant room for improvement before they can effectively facilitate automated abuse detection across a broader range of contexts, languages, and types of media because of implicit bias and other challenges (discussed in detail in Section V). They are also still prohibitively expensive to train, let alone deploy, maintain, and retrain to ensure accuracy over time, which poses a significant barrier to their widespread adoption.85Craig Smith, “What Large Models Cost You – There Is No Free AI Lunch,” Forbes, January 1, 2024, forbes.com/sites/craigsmith/2023/09/08/what-large-models-cost-you–there-is-no-free-ai-lunch. So while LLMs and GenAI have the potential to supercharge online abuse, as well as to improve its automated detection, the degree to which they will be helpful or harmful remains to be seen.

Section IV: Why Don’t Platforms Do More to Reduce Exposure to Online Abuse?

The technology to treat online abuse more like spam exists. While detecting and filtering abuse is considerably more challenging than detecting and filtering spam—as discussed in detail in the next section—it is doable. In fact, platforms have been using the baseline technology that enables the automated detection of potentially harmful content for years for their own internal content moderation systems. Platforms like YouTube, Reddit, Twitch, and Bluesky, as outlined in Section II, are experimenting with giving users access to limited aspects of such technology, but no platform has yet built a robust, comprehensive mechanism akin to the one we propose.

Most of the sources we interviewed agreed that taking inspiration from spam to reduce exposure to online abuse was well worth trying. Given that this idea has been around for at least seven years, why haven’t some of the wealthiest technology companies—which are routinely criticized for inadequately addressing abuse on their platforms—implemented it?

Building robust anti-harassment mechanisms—particularly proactive detection and quarantine measures—requires significant investment of time, energy, money, and staff. According to nearly all of our sources, many of whom have worked in the technology industry, investing in tools to alleviate online abuse is simply not a high priority for most major technology companies. “You need people [i.e., staff] to solve this problem and you need to really invest in it,” says Caroline Sinders, founder of human rights design agency Convocation Design + Research. “And companies don’t seem to want to do that.”86Caroline Sinders, interview by Yael Grauer, Consumer Reports, December 14, 2021.

Indeed, most major technology companies added abuse mitigation mechanisms only retroactively, after years of intense activism and public pressure. As mentioned in the introduction, Twitter (now X) did not integrate a reporting button until 2013, seven years after the app launched in 2006, and only after public outcry.87Alexander Abad-Santos, “Twitter’s ‘Report Abuse’ Button Is a Good, But Small, First Step,” The Atlantic, July 31, 2013, theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/07/why-twitters-report-abuse-button-good-tiny-first-step/312689/; Abby Ohlheiser, “The Woman Who Got Jane Austen on British Money Wants To Change How Twitter Handles Abuse,” Yahoo News, July 28, 2013, news.yahoo.com/woman-got-jane-austen-british-money-wants-change-024751320.html. In 2017, more than 13 years after it was created, Facebook finally allowed users to quarantine direct messages sent from abusive accounts without having to block the abusive user;88Antigone Davis, “New Tools to Prevent Harassment,” About Facebook, December 19, 2017, about.fb.com/news/2017/12/new-tools-to-prevent-harassment/. the platform only allowed users to report abuse on someone else’s behalf in 2018.89Antigone Davis, “Protecting People from Bullying and Harassment,” About Facebook, October 2, 2018, about.fb.com/news/2018/10/protecting-people-from-bullying/. When Instagram launched in 2010, users could report abuse only through a separate form and were advised to manually delete abusive comments;90“User Disputes,” Wayback Machine, October 18, 2011, accessed February 16, 2021, web.archive.org/web/20111018040638/help.instagram.com/customer/portal/articles/119253-user-disputes. it did not introduce a mute button until 2018.91Megan McCluskey, “Here’s How You Can Mute Someone on Instagram Without Unfollowing Them,” TIME, May 22 2018, time.com/5287169/how-to-mute-on-instagram/. Twitch launched Shield Mode, a customizable safety feature, only after prominent livestreamers staged a virtual walkout in response to prolific “hate raids”—extreme, coordinated abuse campaigns—that had occurred a year prior.92Ash Parrish, “After weeks of hate raids, Twitch streamers are taking a day off in protest,” The Verge, August 31, 2021, theverge.com/2021/8/31/22650578/twitch-streamers-walkout-protest-hate-raids; Jon Fingas, “Twitch’s new ‘Shield Mode’ is a one-button anti-harassment tool for streamers,” Engadget, November 30, 2022, engadget.com/twitch-shield-mode-anti-harassment-180003661.html.

The negligence of technology companies runs deeper than indifference. Many researchers have made the case that the incentives to meaningfully reduce the amount of hateful and harassing content on social media platforms are misaligned. There is broad consensus that user engagement is a critical component to platform success because it drives ad revenue. Researchers have highlighted how technical architecture, which is fundamentally focused on boosting engagement, can increase abusive behaviors online.93Luke Munn, “Angry by Design: Toxic Communication and Technical Architecture,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7, no. 53 (July 2020): doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00550-7. The result of such incentives, Kent Bausman, PhD, a sociology professor at Maryville University in St. Louis, said in a 2020 Forbes article, is that social media “has made trolling behavior more pervasive and virulent.”94Peter Suciu, “Trolls Continue to be a Problem on Social Media,” Forbes, June 4, 2020, forbes.com/sites/petersuciu/2020/06/04/trolls-continue-to-be-a-problem-on-social-media/.

Several of our sources concurred, arguing that because publicly held companies are driven by increasing profit for shareholders, they are unlikely to engage in steps that reduce online abuse if creating a safer, less toxic space for users would significantly impact their bottom line. “These companies are for profit companies,” says Susan McGregor, a research scholar at Columbia University’s Data Science Institute. “Most of them are publicly held. They have a legal obligation to maximize their profitability in the absence of regulation to the contrary … to protect their shareholders’ interest. … Speech that is abusive and harassing towards an individual or a group on social media is abuse and harassment, as far as the targets are concerned. To platforms that host it, it looks like engagement, and engagement equals advertisers.”95Susan McGregor, interview by Yael Grauer, Consumer Reports, December 2, 2021.

We encountered a different perspective from trust and safety professionals who have worked in the tech industry to develop and enforce policies that define acceptable behavior and content online.96“About Us,” Trust & Safety Professional Association, October 14, 2022, tspa.org/about-tspa/. Many trust and safety experts argue that effective content moderation and anti-abuse mechanisms should be aligned with platforms’ growth incentives. The Trust & Safety Professional Association, for example, states, “Content moderation is also a required business investment to ensure the desired traffic and growth to the platform…. as it directly influences user trust and brand reputation, which in turn influences growth and revenue.”97“What is Content Moderation?” Trust & Safety Professional Association, September 19, 2022, tspa.org/curriculum/ts-fundamentals/content-moderation-and-operations/what-is-content-moderation/.

Some research also suggests that a safer, more inclusive online environment is more sustainably profitable than an economy of abuse. A 2018 report found that women were 26% less likely to use the internet than their male counterparts, with many women citing safety concerns, including online abuse, as a reason they limit their internet usage.98Oliver Rowntree, “The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2018,” GMSA, February 2018, gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/GSMA_The_Mobil e_Gender_Gap_Report_2018_32pp_WEBv7.pdf. A 2023 study by the National Democratic Institute found that efforts to create a more safe and inclusive environment, particularly for marginalized groups like women, can lead to better reputation and greater brand loyalty for a company. According to the study, some companies, like Bumble, have taken harm reduction more seriously because it is tied directly to brand and overall financial outcomes.99Theodora Skeadas and Kaleigh Schwalbe, “Technology Companies Must Make Platforms Safer for Women in Politics,” Technology Policy Press, August 22, 2023, techpolicy.press/technology-companies-must-make-platforms-safer-for-women-in-politics/.

“In the context of commercial platforms, revenue and growth pressure is the primary driver … and those pressures lead towards moderation,” says Yoel Roth, technology policy fellow at UC Berkeley and formerly head of Trust and Safety at Twitter (now X). “Advertisers are a profoundly influential force on the decisions that ad-supported platforms make. If your goal is safety, advertisers are pretty much on the same page and have … actually pushed companies to do more.”100Yoel Roth, interview by Yael Grauer, Consumer Reports, and Deepak Kumar, PEN America and University of California San Diego, December 19, 2023. In other words, too much abusive and harmful content may drive both users and advertisers away from the platform, therefore undercutting companies’ growth and profit goals.

We have seen this effect borne out recently with X. In October 2022, tech entrepreneur Elon Musk bought Twitter and soon renamed the platform X. Under the guise of saving money and protecting free speech, X, under the leadership of Musk, drastically cut the company’s Trust and Safety staff, restored alt-right accounts that had previously been banned for violating platform policies on hate and harassment, and weakened the platform’s popular block feature.101Jyoti Mann, “Layoffs, Long Hours and RTO: All the Changes and Controversies in the 12 Months Since Elon Musk Bought X,” Business Insider, July 27, 2023, web.archive.org/web/20240102033411/https://www.businessinsider.com/elon-musk-twitter; Chris Vallance and Shayan Sardarizadeh, “Tommy Robinson and Katie Hopkins Reinstated on X,” BBC, November 6, 2023, bbc.com/news/technology-67331288; Robert Hart, “Elon Musk Is Restoring Banned Twitter Accounts–Here’s Why the MostControversial Users Were Removed and Who’s Already Back,” Forbes, August 18, 2023, forbes.com/sites/roberthart/2022/11/25/elon-musk-is-restoring-banned-twitter-accounts-heres-why-the-most-controversial-users-were-suspended-and-whos-already-back/; Emma Roth and Kylie Robison, “X will let people you’ve blocked see your posts,” The Verge, September 23, 2024, https://www.theverge.com/2024/9/23/24252438/x-blocked-users-view-public-posts.

Hate and harassment drastically spiked on the platform; studies from the Center for Countering Digital Hate have shown that X failed to remove 86% of tracked hate speech posts, that posts involving anti-Black slurs rose a staggering 202%, and that anti-LGTBQ+ extremists gained followers at quadruple the pre-Musk rate.102“The Musk Bump: Quantifying the rise in hate speech under Elon Musk,” Center for Countering Digital Hate, December 6, 2022, counterhate.com/blog/the-musk-bump-quantifying-the-rise-in-hate-speech-under-elon-musk/; “X Content Moderation Failure,” Center for Countering Digital Hate, September 2023, counterhate.com/research/twitter-x-continues-to-host-posts-reported-for-extreme-hate-speech/. X has since seen a 59% decrease in advertising revenue because a significant number of advertisers became increasingly reluctant to buy ads on the platform in part out of fear that their brands would appear next to hateful or harassing content that could tarnish their reputation.103Ryan Mac and Tiffany Hsu, “Twitter’s U.S. Ad Sales Plunge 59% as Woes Continue,” The New York Times, June 5, 2023, nytimes.com/2023/06/05/technology/twitter-ad-sales-musk.html.

Technology companies have historically underinvested in trust and safety teams and are increasingly downsizing them further. X, for example, has cut 43% of its Trust and Safety staff since 2022.104Ben Goggin, “Big Tech companies reveal trust and safety cuts in disclosures to Senate Judiciary Committee,” NBC News, March 29, 2024, nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/big-tech-companies-reveal-trust-safety-cuts-disclosures-senate-judicia-rcna145435. As Anika Navaroli, senior fellow at Columbia Journalism School and former senior policy official at Twitter (now X) and Twitch, said, “Even when trust and safety was at its heyday, we still didn’t have the investment and the resources for folks to be able to say, we’re going to take this engineering team off of building this product that we think is going to bring in all of this revenue, so that you can think about abuse. … it doesn’t get to the bottom line.”105Liz Lee and Anika Navaroli, interview by Deepak Kumar, PEN America and University of California San Diego, May 7, 2024.

This is underscored by the fact that platforms regularly insist that their trust and safety teams calculate and demonstrate a positive return on investment (ROI) to justify the cost of programs and features to reduce harm, which many trust and safety professionals have noted is a difficult calculation and may not always offset the costs of developing robust moderation and safety systems.106Alice Hunsberger, “Don’t fall into the T&S ROI trap,” Everything in Moderation, April 8, 2024, everythinginmoderation.co/trust-safety-roi-trap/.

During the tech recession of 2023, major companies like Meta, Amazon, Alphabet, and X (formerly Twitter) all drastically cut the size of their trust and safety teams further.107Hayden Field, “Tech Layoffs Ravage the Teams That Fight Online Misinformation and Hate Speech,” CNBC, May 26, 2023, cnbc.com/2023/05/26/tech-companies-are-laying-off-their-ethics-and-safety-teams-.html. Despite the fact that online abuse, rapidly accelerated by developments in technology like generative AI, is more urgent than ever, major technology companies continue to deprioritize the issue. As Theodora Skeadas, chief of staff at Humane Intelligence and former associate on public policy at Twitter (now X), said: “The layoffs speak for themselves. It shows where the priorities are.”108Theodora Skeadas, interview by Deepak Kumar, PEN America and University of California San Diego, January 5, 2024. Technology companies often invest in robust trust and safety measures only if they are incentivized by public pressure, government regulation, and impact on their bottom line to do so.

Section V: What Are the Challenges With Automatically Detecting Online Abuse?

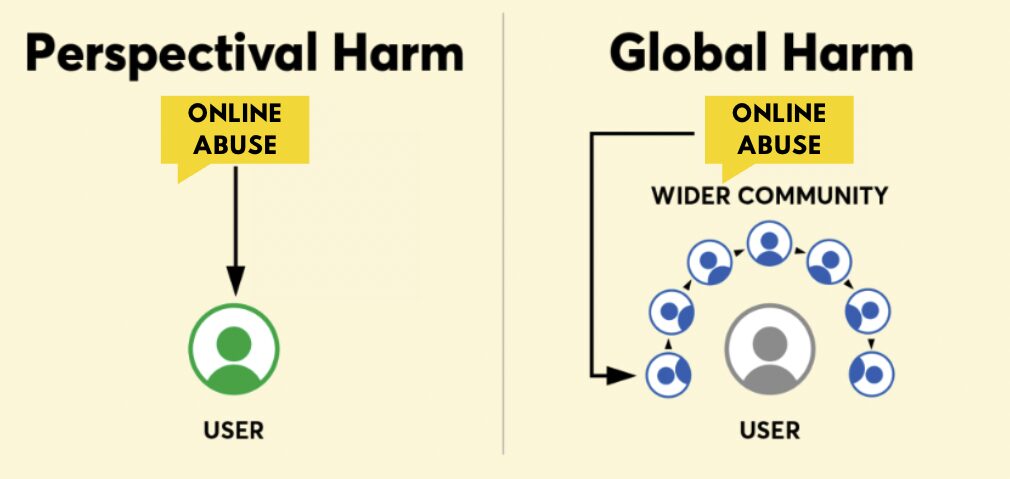

Spam and online abuse have numerous similarities. For both, the targeted user receives content that is essentially unwanted. And both come with legitimate harms: Spam primarily poses a financial or cybersecurity threat, and online abuse can have serious psychological impacts and can even undermine physical safety.109HRC Staff, “New Human Rights Campaign Foundation Report: Online Hate & Real World Violence Are Inextricably Linked,” Human Rights Campaign, December 13, 2022, hrc.org/press-releases/new-human-rights-campaign-foundation-report-online-hate-real-world-violence-are-inextricably-linked. However, there are important differences that make abuse more complicated than spam to automatically detect and quarantine. Below we discuss a range of challenges revolving primarily around context, bias, and the ability of models to keep up with the speed that human language evolves. It is important to note that most of these challenges are inherent to automated detection technology, whether deployed exclusively by platforms behind the scenes to facilitate content moderation or also provided to individual users to empower them to shape their own online experiences.

More complex detection signals

Technology companies, from email providers to social media companies, use multiple different signals to automatically detect both spam and abuse. These signals rely not only on analyzing the content of a message but also on metadata, which is data about the message, such as email headers (which spammers often forge) or IP addresses (a unique string of numbers that identifies each device on the internet).

Volume, for example, is a particularly useful signal for spam because spammers will utilize hundreds of thousands of bots to coordinate large-scale campaigns to target as many people as possible.110Brett Stone-Gross et al. “The underground economy of spam: a botmaster’s perspective of coordinating large-scale spam campaigns,” 4th USENIX Conference on Large-scale Exploits and Emergent Threats, (March 2011), 1-4, usenix.org/legacy/event/leet11/tech/full_papers/Stone-Gross.pdf. As spam tends to operate at scale, defenses against spam are also deployed widely; there are multiple companies, for example, that track the specific IP addresses and domain names (web addresses) associated with spam and that provide technology companies with up-to-date block lists. Finally, the ubiquity of spam enables “collaborative” filters, which can automatically flag a message as spam for all users once a critical mass of users have manually marked that message as spam.111Saadat Nazirova, “Survey on spam filtering techniques,” Communications and Network 3, no. 3 (August 2011): 153-160, dx.doi.org/10.4236/cn.2011.33019.