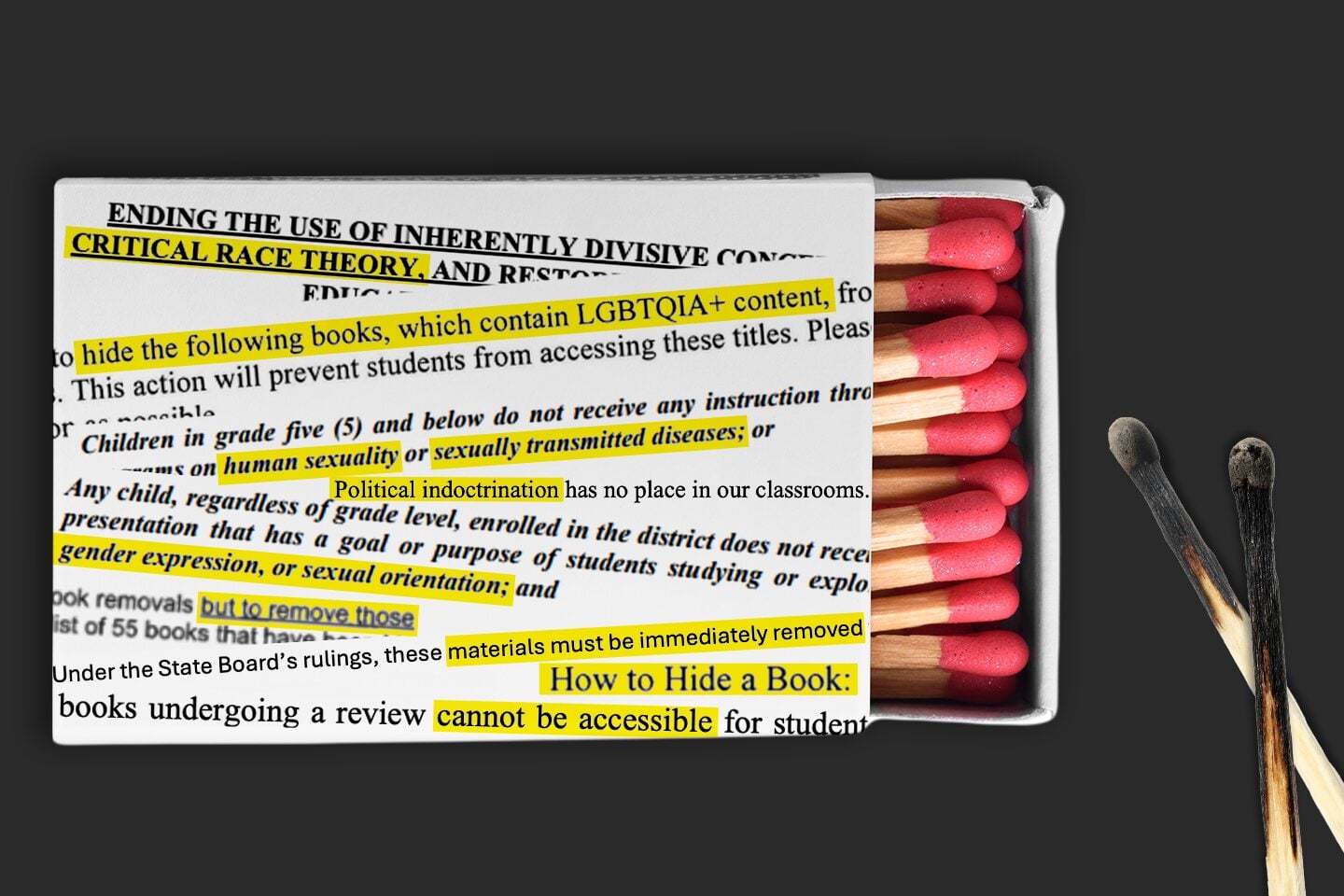

The Bills Igniting Book Bans

Evolving State Legislative Efforts to Censor Public School Libraries

PEN America Experts:

Manager, State Policy, U.S. Free Expression Programs

Program Coordinator, Freedom to Read

Director, Freedom to Read

Introduction

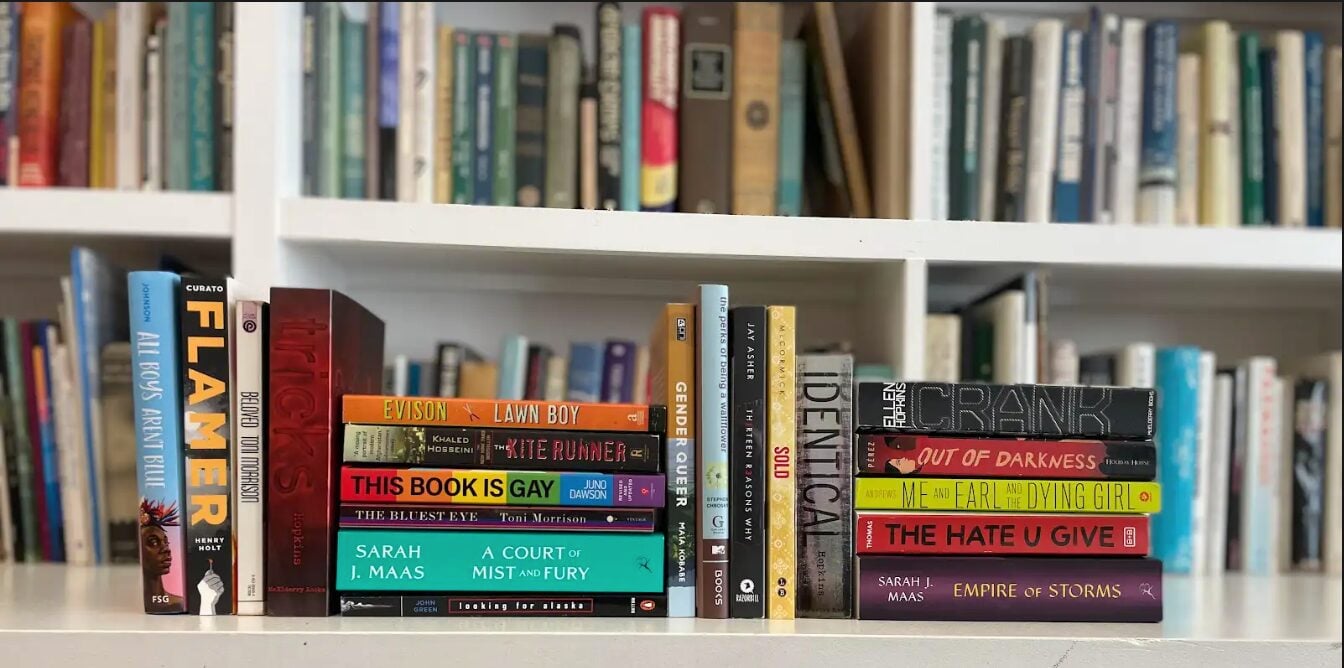

Thousands of books removed from schools out of fear of state governments nationwide. Judy Blume’s Forever… banned from every Utah public school; To Kill a Mockingbird and 39 other titles pulled from a Texas school district that used AI to review materials; a list of 400 titles removed in one district quietly circulated in Tennessee as a resource for other school administrators to find books to ban; 22 titles barred from all South Carolina school districts after the state board of education deemed them inappropriate.

Five years ago, these stories may have felt more fitting in a dystopian novel or a satirical publication. But for public schools and libraries across the country, instances like these are the new normal. What began in 2020 with politicians’ threats to defund schools that used curricula from the New York Times’ 1619 Project has snowballed into a multifaceted campaign to impose a narrow vision of what should be taught or read in schools. PEN America has characterized this campaign as the “Ed Scare”, an effort to create fear and anger within the public, with the goal of suppressing free expression around gender, race, sexuality and sex-related content in public schools and public libraries.

To date, PEN America has recorded nearly 23,000 book bans in public schools since 2021, and while book bans are not new, an explosion of well-organized, political organizations putting pressure on local school districts and library boards marked the emergence of something unprecedented. By 2022, these highly localized efforts converged with the passage of state-level legislation: educational gag orders, educational intimidation bills, and other state proposals seeking to suppress free expression in education. Some laws imposed direct prohibitions on instruction by restricting teaching about topics such as race, gender, American history, and LGBTQ+ identities; others used indirect means to chill speech, such as criminal punishments and other penalties. Taken together, state laws inflamed a campaign to ban books.

In this policy brief, we describe the evolving ways in which state laws are propelling book bans at the local level and the impact they are having on schools and students. Ignited by misleading “parents rights” rhetoric, coupled with moral panic over what’s in schools, organizations and elected officials have proposed and enacted laws designed to censor. Following a blueprint that originated from Florida politics, the results chip away libraries’ autonomy, students’ right to read, and public education as we know it.

Since 2021, PEN America has tracked school book bans and cases in which districts cited a state law or policy as the justification for bans. The below map illustrates states where state law or policy were directly linked to book bans in our indexes from Fall 2023 through Spring 2025. This is not comprehensive of all book ban-related legislation, but does offer a look into how common these laws are cited in book banning.

States With Documented Book Bans Driven By Legislation Over The Last Two Years

Please note that this table only notes book ban-related provisions; additional provisions enacted by any listed bills are excluded.

Book Bans By Law

Educational Gag Orders and Direct Prohibitions on Concepts and Identity

Beginning in 2021, a wave of state laws restricting teaching about topics such as race, gender, American history, and LGBTQ+ identities in K-12 and higher education spread across the country. As these educational gag orders were enacted, book bans soon followed in states like Florida, Georgia, Oklahoma, Iowa, Kentucky, and North Carolina. Using vague language to weaponize anti-racism narratives, this type of law often asserts that certain portrayals of history or discussions of social issues are discriminatory or designed to assign “guilt” or “responsibility” to students based on identity, or claim the information and representation of different sexualities and gender identities may be “harmful.” Stoked by campaigns falsely alleging “indoctrination” and “harm” by far-right think tanks, “grassroots” organizations, elected leaders, and conservative activists, state governments have enacted 51 bills and policies with direct prohibitions on K-12 instruction from 2021 through 2025, impacting classrooms and libraries across the country.

One of the earliest educational gag orders, Florida’s HB 7 (the “Stop WOKE Act,” enacted in 2022), prohibits instruction on certain concepts relating to race, color, sex, and national origin. In its wake, school districts banned books in an attempt to comply with the law. That same year, the state also passed HB 1557 (colloquially known as the “Don’t Say Gay” law) prohibiting “classroom instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity” in grades K-3. In 2023, the state expanded the ban through 12th grade.

Following in Florida’s footsteps, many “Don’t Say Gay” gag orders were passed in other states thereafter. Iowa’s iteration, SF 496 (2023), landed the state as the second highest in book bans for the 2023-2024 school year: over 3,000 books were pulled from schools to comply with the new law. In South Carolina, since 2021, the state’s education gag order has been enacted annually through the budget and prohibits several listed concepts related to race and sex. In 2022, it led to bans on Stamped by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi and Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates. In the case of Between the World and Me’s censorship, several students reported their AP Language Arts teacher for its inclusion and the surrounding lesson plan, on the basis that they felt uncomfortable, directly referencing the state policy: “I am pretty sure a teacher talking about systemic racism is illegal in South Carolina.”

The language within these restrictions singles out materials representing certain identities for extra scrutiny, providing proponents of censorship a tool to say that books about race or racism, or with any LGBTQ+ people or themes, regardless of the nature of the content itself, are “divisive” and not “appropriate” for children and teenagers in schools.

Weaponizing Obscenity Law to Directly Prohibit Books with Sex

State laws and policies are also driving book bans under the guise of removing content that is pornographic, obscene, or “harmful to minors.” Obscene materials are already not permitted in schools, but some legislators are pushing a narrative that schools are providing obscene materials to minors. To date, several states have enacted laws that twist or altogether ignore the court-established definitions of “obscenity” and introduce broad, vague or undefined terms like “sexual conduct” or “sexually relevant” into education statutes. These laws may also threaten punishment for librarians and educators, including criminalization, license revocations, and monetary fines. The result has been widespread confusion and fear of punishment contributing to rising bans on books that discuss or reference sexual consent, puberty, and abuse as well as sexuality.

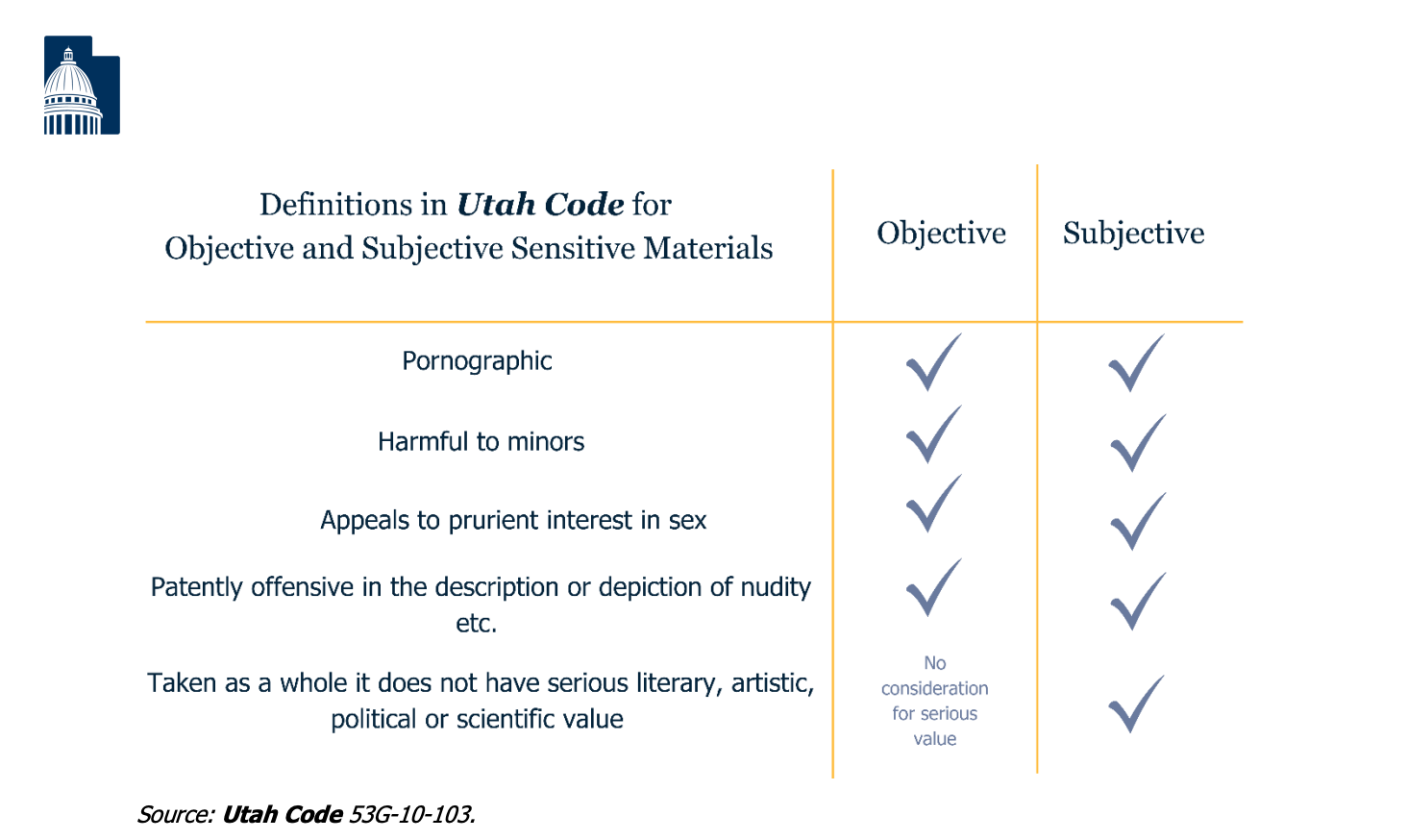

The Miller Test: A Legal Definition for Obscenity

While obscenity is the one established exception to expression protected by the First Amendment, it is often invoked by groups claiming that a book is inappropriate to have in a school. Swaths of books have been removed due to claims of inappropriate sexual content, but the United States Supreme Court’s Miller test for when material is obscene, and therefore unprotected, is much more stringent than might be presumed based on book banning narratives.

A material is only “obscene” if all three prongs of the Miller test are true:

- the average person applying contemporary community standards would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest;

- the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and

- the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.

Missouri’s SB 775, passed into law in 2022, created a criminal misdemeanor offense specific to school employees for providing visual depictions of sexual conduct to a student, with few exemptions. Even though the law applies only to visual depictions and includes some parts of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Miller Test, nearly 300 books were pulled across the state in the months following the bill’s enactment. In November 2025, the law was struck down by a state judge for being unconstitutionally vague and overbroad.

Other provisions intended to ban sex-related content from school libraries have appeared in dozens of bills around the country, some becoming law. Georgia’s SB 226 (2023) gives district administrators just 10 days after a material is challenged to decide whether its content is “harmful to minors.” Under HB 1069 in Florida, books that are alleged to be inappropriate for describing “sexual conduct” have to be removed from library shelves within five days, even before they are reviewed. Two similar laws in Idaho and Arkansas target both sex-related content and LGBTQ+ representation in books, requiring libraries to ensure noncompliant books are physically inaccessible to certain age groups. Idaho’s requires public schools and libraries keep these books in adult sections; Arkansas’ requires K-5 schools keep them in locked storage.

In Texas, legislators went even further, placing responsibility on booksellers to screen materials before selling them to schools and on librarians to audit their collections, by requiring them to apply a ratings system based on vaguely-defined categories, such as whether a book is “sexually explicit” or “sexually relevant”. The law, HB 900, has since been partially struck down in court, but not before school leaders removed books as they attempted to comply with its impossible mandate.

Utah, South Carolina, and Tennessee’s laws targeting sex-related content create de facto statewide “no read lists” within their state’s public schools. All three have established mechanisms for specific titles to be banned from every public school if they are deemed “sensitive” or “inappropriate” because of sex-related content; in Tennessee’s case, the mechanism can also be applied to violence-related content. Utah’s law, HB 29 (2024), functions as a “trigger ban,” where a book is automatically banned statewide if a certain number of school districts or charter schools remove it from their shelves. Nineteen different titles have been banned from public schools across the state after only a few schools removed them. Both Tennessee’s HB 843 (2024) and South Carolina’s Regulation 43-170 establish mechanisms for a state-level board or commission to decide whether books should be banned statewide. Using this authority, the South Carolina Board of Education has so far mandated 22 statewide book bans, 14 of which were a result of just one parent requesting review.

Chart of the definitions of “objective” versus “subjective” sensitive materials under Utah’s HB 29 (2024) from the Utah Office of the Legislative Auditor General Performance Audit of Sensitive Materials in Schools.

Despite the fact that school libraries do not contain obscene content, these laws result in book bans by successfully instilling fear of criminal punishments and other penalties. Though no librarians have been charged for providing books to young people, some have been threatened with criminal charges by library patrons, law enforcement, conservative activists, or political figures. In addition to several laws that establish criminal punishment for violations, schools can also face hefty fines, revoked funding, or the removal of educator and librarian licenses under some of these laws. For those seeking to expand book bans and educational censorship, weaponizing obscenity laws and manipulating the definition of sexual content has been an effective tactic, especially when combined with other mechanisms that force removal of books across multiple school districts all at once.

Expanding Parental Control

Another tactic that has spread in recent years is establishing new forms of parental control over public education’s offerings in state law. This has become a popular tactic of legislators who are eager to eradicate certain ideas from public schools, enabling parents to censor, rather than censoring schools themselves through direct restrictions. Misnomered as “parental rights” laws, these provisions tend to operate more subtly, but ultimately grant some parents the ability to circumvent the expertise of educators and librarians, the interests of other parents, and students’ First Amendment rights.

Parental control works in a number of ways. For example, “Parents’ Bill of Rights” laws often include curriculum and library inspection provisions, requiring not only that materials must be publicly posted for students’ parents to review and object, but also inviting general members of the public to lodge complaints against school districts’ selections. Florida’s HB 1069 (2023) includes several measures that extend parental control, namely a process for parents to limit their students’ library access and a provision that requires an immediate, permanent book ban if a school board stops a parent from reading a passage during a school board hearing. This goes beyond sensible reconsideration practices, facilitating book bans based on out-of-context content, rather than on the consideration of a material as a whole.

Another example are “education a la carte” provisions which significantly expand parents’ ability to “opt out” of materials or even require “opt-ins” for certain topics. Such mechanisms can incentivize schools and teachers to remove books that parents opt out of or that they think parents might opt out of to avoid the significant administrative burden of creating alternate lesson plans or responding to book objections. Opt-ins can be even more burdensome. Arizona’s HB 2495 (2022), for instance, prohibits public school employees from using or referring students to materials with any content that meets a broad definition of “sexually explicit”, unless the parent opts the student in to the material. Laws like this may not mandate book bans, but the massive burden of securing every parent’s permission for every material that might be construed as “sexually explicit” could easily lead to book bans under the auspices of upholding “parental rights.”

Mahmoud v. Taylor and Expanding Opt-out Rights

Following the decision this summer in, Mahmoud v. Taylor, the U.S. Supreme Court held that public schools must now allow a parent to opt their child out of any instruction, activities, or assignments following a religious objection. The ripple effects of the ruling are vast with some state legislatures choosing to even go beyond the SCOTUS decision.

In North Carolina, for instance, a newly-passed law mirrors the decision for curricular matters as argued in Mahmoud v. Taylor, and gives parents the same right in regard to library books as well. Public schools must post a catalog online that lists every book in a school or classroom library and allow parents to bar a student from checking out any book they oppose, for any reason. As seen in the case of Mahmoud v. Taylor, mandating such broad opt-out provisions for classroom instruction and reading materials will likely lead to heightened suppression of books with LGBTQ+ representation in schools across North Carolina.

Public schools should rely on professional expertise in collaboration with parents to best serve the broadest number of students possible. Parental control laws instead stoke distrust in education professionals in an attempt to remake public school systems according to certain parents’ ideologies, and in direct disregard of the freedom to read and learn.

Why Choose? The Rise of Omnibus Bills

As laws that lead to book bans proliferate, legislators are increasingly combining varied approaches to banning books into a singular bill. Many bills with gag order provisions restricting classroom instruction also now force an end to programming focused on advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion; some “Don’t Say Gay” bills also censor sex-related content.

One of the most illustrative examples of omnibus book banning legislation is found in Texas. Now law, SB 13 (2025) adds a prohibition on “indecent” or “profane” content to existing school library restrictions that were passed back in 2023, requires immediate removal of any materials that are challenged (regardless of whether the challenge has merit), and allows parents to select (opt-out of) materials they don’t want their child to access. But legislators didn’t stop there; they also created a new avenue for parental control. With the enactment of SB 13, parents can petition a school district to create a parent advisory council, where a few parents will be given a disproportionate level of input in shaping school library collections. If just 10 percent of a school district’s parents sign the petition, the school district must establish the council.

Laws that combine a wide array of provisions force schools to quickly adhere to an onslaught of new and complex restrictions in a short time frame. In some states, like Florida, schools are facing at least one new law censoring library materials or classroom topics nearly every year, and these laws are, generally, becoming more convoluted with each new legislative session. In 2025, these omnibus censorship laws are increasingly common. The challenges of complying with provisions that censor education and library materials are endless, especially for the librarians and teachers on the frontlines, who are increasingly likely to remove books with topics that might incur any controversy, or avoid purchasing or teaching such books in the first place.

Challenges and Impacts of Responding to State Laws

The implementation of this legislation–assessing and removing books, locking them up, informing all school staff which materials are contraband–places a significant administrative and financial burden on school districts; further, many laws give schools only months, weeks, or even no time at all to fall into compliance after the bill is enacted. Across the country, public schools are being forced to jump through hoops, often ill-defined, to avoid violating the law.

The confusion caused by these laws also drives a chilling effect across public schools as they rush to follow them, where it’s often simpler to pursue paths of least resistance, by removing books to avoid any potential controversy or difficulty with any parents or politicians. The role of lawsuits and state officials’ directives add further confusion, and often provide conflicting information as to the correct interpretation of legislation. Library materials are being swept up in vague, overly broad language or misinterpretations of laws that actually apply more narrowly. The misapplication or overapplication of such policies has devastating consequences for students.

Confusion Leads to Misapplication and Overcompliance

Cases of school districts misunderstanding what educational spaces restrictions apply to are an increasingly expected consequence of policies that prohibit classroom and library content. One of the earliest and well-known instances of this was Florida school districts’ implementation of the 2022 “Don’t Say Gay” law (HB 1557). The law only applied to classroom instruction and did not require schools to purge their library shelves, but schools across the state have cited the law as the reason for removing thousands of books. Elsewhere, in South Carolina, the state’s ACLU described a pattern of “irregular” enforcement following their statewide book ban policy. In “complying” with the state’s rules, school districts are implementing inconsistent restrictions and revoking access to a range of physical library books, classroom libraries, research databases, digital ebook/audiobook collections, and book fairs.

Confusing state laws have also led to districts “complying” well beyond legislative mandates. Kentucky’s SB 150 (2023), for example, is a “Don’t Say Gay” gag order prohibiting instruction about LGBTQ content that also allows parents to review the full curriculum of sex education classes, and opt into, rather than out of, sex education classes. The law led to 100 books being incorrectly pulled by a district, which only returned them to the shelves after the state issued guidance specifying the law did not apply to libraries. In Virginia, a 2025 audit from their Legislative Audit and Review Commission found that multiple school districts in the last few years pulled library books by similarly misapplying SB 656, a bill that was passed in 2022. That law requires schools to notify parents and allow opt-outs before materials with “sexually explicit content” can be assigned in the classroom–but it does not apply to materials available in libraries, nor does it require the full removal of materials from even classroom instruction. Yet, the report states that the law was frequently cited as reason for removal of books from school libraries.

Unconstitutionality of Vague, Overly Broad Laws

2025 saw the passage of one of the most extreme educational censorship laws to date in Mississippi. HB 1193 is titled as simply a prohibition on “DEI,” an example of legislators and proponents of censorship obscuring the full extent of their policy proposals by leaning into the use of popular right-wing boogeymen. In addition to a gag order on “divisive concepts” and a ban on diversity, equity, and inclusion programming, the law would prohibit any required “formal or informal education” or program that “increases awareness or understanding of issues related to race, sex, color, gender identity, sexual orientation or national origin.” By applying the prohibition to “informal education” and “programs,” it could be easily construed that libraries must clear their shelves if the law were to be enforced. This particular provision and the prohibition on “divisive concepts” were enjoined by a federal district court for violating the First Amendment, though other provisions unfortunately remain in effect.

In Tennessee, the mechanism created by the 2024 law to ban books statewide has not yet led to any state-level decisions mandating book bans statewide, but hundreds of books were still pulled across the state due to fear and confusion around compliance. Some districts circulated an informally compiled “resource” listing 400 titles to consider for potential removal. One district instructed its teachers to temporarily halt usage of all classroom libraries, and another school briefly closed its entire school library. This has occurred in other states too; an audit from Utah’s state government this year acknowledged that many districts were pulling books in a manner that was inconsistent with what the state saw as required under HB 29 (2024), including halting the use of classroom libraries or believing that the threshold for books to be removed statewide was if they had been removed in only one district, not three.

Shortcuts to Compliance

The burden of these laws also leads many districts to attempt “shortcuts” to comply with new mandates. Districts in South Carolina report using Goodreads and the now-defunct BookLooks, instead of professional reviews, to assess potential book purchases for “compliance” with state law. In 2024, a state senator sent Iowa librarians a formal letter that included a list of books compiled by a local Moms for Liberty group to assist in “removing inappropriate materials.” More recently, numerous Texas school districts confirmed they are using AI as an auditing tool to comply with the newly-enacted restrictions on libraries in SB 13 and a ban on diversity, equity, and inclusion in another law, SB 12. This has already led to instances of the technology “hallucinating” prohibited content in books where it did not exist, underscoring the danger of circumventing librarians’ expertise in review processes.

State Guidance Misleads

Where state governments attempt to “clarify” vague legislation, it often results in guidance that further restricts students’ First Amendment rights or creates additional confusion and inconsistency. Utah’s initial state guidance interpreting its state book ban law further barred students from bringing their personal copies of books that are included in the state’s “no read list” to school; the state then reversed course following outcry from free expression groups. State Superintendent Ellen Weaver sent out a poor attempt at “clarification” of South Carolina’s book ban law in February of this year, saying that a description of sexual conduct meriting removal requires “enough ‘explanatory detail’ to form a mental image of the conduct occurring.” The memo lists George Orwell’s 1984 as a title that doesn’t violate this, but advocates have pointed out that other titles the State Board voted to ban have content similar to 1984’s. This has created further uncertainty about what the state sees as objectionable. Meanwhile, Florida’s state government has time and time again sent statewide or district-specific guidelines or memos regarding library materials that stoke chaos and fear in Florida school districts. In 2023, the state’s mandatory librarian training stated outright that considerations for library collections should “err on the side of caution.”

Across the board, librarians and educators across the country are facing requirements so impossible to implement that even government officials are unable to provide consistent, reliable guidance for them. Instead, the cycle of confusion, fear, and censorship continues.

Impacts Go Beyond Removals

Setting up libraries to operate under restrictive laws is expensive and time consuming. In some states, libraries have to create storage to lock up books or a plan for staff to act as psuedo-bouncers for 18 and over sections of their library. This has led to absurd stories of enforcement, such as a mother in Idaho being turned away from the “adult section” of her public library because her infant didn’t have a library card, due to a law impacting both public schools and libraries. Some states are estimated to be spending millions to comply with restrictive laws.

Sweeping restrictions on library books disregard education professionals’ expertise and ignore longstanding sensible systems in libraries. Instead of ensuring collections are curated according to the various needs of students in K-12 public schools, blanket or universal prohibitions in some states restrict high schoolers to only access books that contain as little sex-related content as books in a kindergarten library.

Most of all, these laws stigmatize books with LGBTQ+ representation, books that talk about racism and depict people of color, and books that discuss sex and sexuality. That stigma is occurring even when certain titles do not meet the state’s definition of prohibited materials. In other words, the efforts to ban books from school libraries are an attempt to erase people and identities from public schools, and that has clear consequences for the people whose identities are being targeted.

Teachers have reported students are more enthusiastic readers when there is a diverse range of books available to them. Students who read for fun tend to be better readers, and some data shows those who read for pleasure might have improved mental health outcomes. Still, books continue to be banned at alarming rates, while reading skills are continuously declining. LGBTQ+ students have reported declining mental health from legislation targeting LGBTQ+ content in schools, as have students of color in the wake of actions censoring discussions of race and BIPOC representation.

Codifying the Right to Read

Amid the harmful legislation being enacted, there are signs of hope that Americans can protect the freedom to read.

States with Right to Read Laws

Campaigns for governors to veto harmful legislation have succeeded in several states, stopping existing censorship from further proliferating. In Ohio, New Hampshire, and North Dakota, Republican governors vetoed legislative proposals this year that would have eroded students’ right to read in those states. These efforts signal a break from partisan preferences, instead prioritizing the First Amendment and the right to read.

Meanwhile, 12 states have passed “Right to Read” legislation: bills attempting to prevent censorship in school and public libraries and protect librarians and staff from retaliation for performing their job duties. Numerous cases of book banning have been halted or reversed using state right to read laws.

California’s Freedom to Read act, which exclusively protects public libraries, was recently invoked to reverse book banning policies in Huntington Beach. Following the adoption of local measures to censor books–including outright restrictions to young people’s library access–a lawsuit was launched against the city, arguing the actions violated the state law. The plaintiffs won, halting an egregious attack on their right to read. Likewise, a lawsuit citing Minnesota’s right to read law led St. Francis Area Schools to return books their school board had removed from library shelves. Students, authors, community members, and a teacher’s union fought back, using the law to force the school district to return the books to library shelves and rewrite their collections policy.

As more states pass laws protecting access to books, right to read advocates should be aware of potential limitations of some enforcement mechanisms. After Illinois passed the first Right to Read law and included a financial penalty for noncompliance, some districts across the state opted to forgo state funding in order to–in their eyes–preserve local control. Those codifying students’ freedom to read should avoid provisions that provide pathways to weaken libraries and instead focus on mechanisms that keep or return books to shelves.

Rhode Island’s Freedom to Read Act models this approach and is the strongest right to read law enacted by any state to date. By enacting SB 238 in July 2025, Rhode Island became the first state to establish a private right of action allowing readers and writers impacted by censorship to sue to keep books on the shelves. The law also requires libraries to follow best practices and establishes vital defenses against criminal prosecution for librarians and school staff.

Four other states enacted a right to read law in 2025–Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, and Oregon. Legislative safeguards in states facing lower rates of book censorship will help ensure their schools never get to the point where hundreds of books are challenged and removed, as seen in other states across the nation.

We Must Resist: Dousing Censorship

The groundswell of legislation causing book bans has been detrimental to the freedom to read and free expression in education, as well as the stability of public education systems as a whole. These laws have had a profound impact on schools and libraries, from thousands of books removed to librarians and educators punished for simply doing their jobs.

State legislatures have been fertile ground for introducing, refining, and enacting laws restricting access to books over the last several years. In 2025, we’re also seeing heightened federal efforts–executive policies and proposed Congressional legislation–wielding the same rhetoric and tactics to impose government censorship of education, libraries, and the arts. Censorship of schools by the federal government is directly referenced in the Project 2025 playbook. The takeover of the Kennedy Center, censorship of Smithsonian museums, the firing of Librarian of Congress Dr. Carla Hayden, and executive orders targeting diversity, equity, and inclusion and trans people all mirror what has been accomplished in many K-12 schools across the country: school board takeovers, libraries vacated of certain materials, and “noncompliant” or otherwise outspoken educators and librarians pushed out of their profession. This multifaceted campaign is anchored in a desire to control not just what topics are taught in schools, but which identities, stories, and histories belong in classrooms and who is deserving of equal rights and representation.

In the defense of free expression and the right to read, it is imperative to resist these laws by following them as narrowly as possible or refusing to follow them at all. There’s evidence of communities resisting, and even winning, these fights across the country, from Oklahoma to Texas, to California. The bravery of students, librarians, teachers, and authors shows the way. Those in favor of censorship seek to divide us, but together, we stand in defense of the freedom to read in schools and are committed to ensuring readers have access to diverse histories, stories, and identities in our books. Our students and our democracy relies on it.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Madison Markham, Freedom to Read program coordinator and Laura Benitez, U.S. Free Expression Programs state policy manager. The report was reviewed and edited by Kasey Meehan, Freedom to Read program director and Jonathan Friedman, Sy Syms managing director, U.S. Free Expression Programs. Additional support was provided by Elly Brinkley, staff attorney, and Freedom to Read experts Sabrina Baȇta, Dr. Tasslyn Magnusson, Yuliana Tamayo Latorre, and McKenna Samson.

This report is informed by our Indexes of School Book Bans and our Index of Educational Gag Orders which is not possible without support from several PEN America colleagues and external consultants. Legislative tracking in 2025 was supported by PEN America state policy intern, Ariona Cook.

We thank the entire Communications team at PEN America for their support of this work.

PEN America is grateful for support from the Endeavor Foundation, Henry Luce Foundation, and the Long Ridge Foundation, which made this report possible. We also thank key partners in this work, including the Florida Freedom to Read Project, the Texas Freedom to Read Project, Annie’s Foundation, ACLU of South Carolina, EveryLibrary, American Booksellers for Free Expression, and Let Utah Read; as well as the contributions of the Censorship News Reports from Kelly Jensen at Book Riot.

Finally, we extend our gratitude to the many authors, teachers, librarians, parents, students, and citizens who are fighting book bans, speaking out in their communities, and raising attention to these issues. We are proud to stand with you in defending the freedom to read.

Learn More

-

The Bills Igniting Book Bans

Learn more about how state laws are propelling book bans at the local level and the impact they are having on schools and students.

-

The Normalization of Book Banning

This report offers a window into the complex and extensive climate of censorship between July 1, 2024 through June 30, 2025.

-

The Blueprint State

A wave of education laws in Florida has had a detrimental impact on the state’s schools, chilling the climate for teaching and learning.

-

Cover to Cover

Introduction In the 2023-2024 school year, there were more than 10,000 instances of banned books in public schools, affecting more than 4,000 unique titles. These mass book bans were often the result of targeted campaigns to remove books with characters of color, LGBTQ+ identities, and sexual content from public school classrooms and libraries. As book

-

Banned in the USA: Beyond the Shelves

For the last three school years, PEN America has recorded instances of book bans in public schools nationwide. In that time, efforts to erase certain stories and identities from school libraries have not only intensified; book bans have become a bellwether of the chilling of public education writ large. As this report on the 2023-24

-

Banned in the USA: Narrating the Crisis

The book ban crisis is often referred to by its numbers. A rising number of bans, more states impacted, more titles implicated. And behind every number, there is a deeper story: the narratives being censored from pages, the overworked librarians and teachers, the authors whose work has been maligned, and the students who see their