Splintered Speech

Digital Sovereignty and the Future of the Internet

PEN America Experts:

Director, Research

Introduction: The New Guard Posts of Cyberspace

The common wisdom used to be that the internet would inevitably make societies more open and free. It would connect people, cutting across cultural and political boundaries. It would offer new opportunities for self-expression. It would give every human being with an internet connection access to the world’s accumulated stores of knowledge and to the digital public square, along with the ability to be their own one-person publishing house. It would be, in the words of internet pioneer John Perry Barlow’s influential 1996 “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” “the new home of Mind,” far above the governments that were futilely attempting to “ward off the virus of liberty by erecting guard posts at the frontiers of Cyberspace.”1John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” archived at the John Perry Barlow Library (digital), Electronic Frontier Foundation, February 8, 1996, eff.org/cyberspace-independence Then, the internet was largely viewed as simply too decentralized, too massive, and too untameable for any repressive government to fully and indefinitely control.

Few people would make such optimistic pronouncements today about either the internet’s inevitably liberalizing effect or its irrepressibility. Between a rising tide of governmental regulation of the digital sphere, and the domination of the digital public square by a handful of social media giants, it turns out that the internet is in fact much more vulnerable to top-down controls than its early techno-utopian champions would have predicted.2One internet pioneer who did warn about this control was Lawrence Lessig, who wrote in his 1999 work Code: And Other Laws of Cyberspace that “There is no reason to believe that architects of the second generation” of the internet would not implement top-down controls, and warned against assuming that “this initial flash of freedom will not be short-lived.” Barlow himself later admitted that he was overly optimistic about the surveillance potential of the internet, saying in one 2015 interview that “I felt that if I were persuasive enough in giving a vision of the future in which the Internet was inherently free and could not be controlled we had a better shot at it. . . I could also see there was never a better system that could inherently be extended for surveillance. Ever. I knew that. I wasn’t stupid. I just wanted to pretend that was not the future.” David Hershkovits, “John Perry Barlow Talks Acid, Cyber-Independence and his Friendship with JFK Jr.,” Paper, April 22, 2015, papermag.com/john-perry-barlow-talks-acid-cyber-independence-and-his-friendship-wit-1427554020.html Additionally, as societies grapple with the digital spread of extremism, disinformation, hate, and harassment, experts and everyday people alike are now calling for greater regulation of social media and other tech titans. Few people now advocate Barlow’s call for all governments to simply “leave us alone.”

Today, governments across the globe are arguing for new powers to regulate the internet within their countries’ borders for national security, economic health, and other fundamental reasons. Much of this new negotiation for control is occurring between governments and the technology corporations that host and arbitrate online public discourse. Still other aspects of this renegotiation involve who controls how the global internet functions at a basic level.

In this struggle for control, there is potential for multiple bad outcomes—including further concentration of power in the hands of states or corporations, the erosion of human rights norms, and the subversion of the internet’s continued potential as a space for expression, emancipation, and cultural exchange.

As governments redraw the boundaries of their own authority over the internet, many leaders have endorsed or invoked “digital sovereignty,” a phrase intended to explain and legitimize more expansive governmental regulation of the digital sphere in the national interest. But different governments have vastly different interpretations of what this sovereignty actually entails–which “sovereign” rights governments should have over their nations’ internet, what the strategic goals of such “sovereignty” should be, and what constitutes national interest.

Because the internet traverses boundaries, many of these “sovereignty” efforts will have effects that stretch beyond any one country’s domestic space or the experiences of its own citizens. Analysts and experts have warned that governmental efforts to silo the internet or our data into national boxes, or to impose conflicting national laws on the internet broadly, risk fragmenting the internet and undermining its connective potential. Moreover, authoritarian leaders have invoked their “sovereignty” to enshrine the power of the state—through rhetoric, through law and regulation, and through technological developments—in ways that either foreseeably or explicitly contravene human rights, including freedom of expression, privacy rights, and the right to be free of arbitrary detention or other acts of state-sponsored violence and repression.

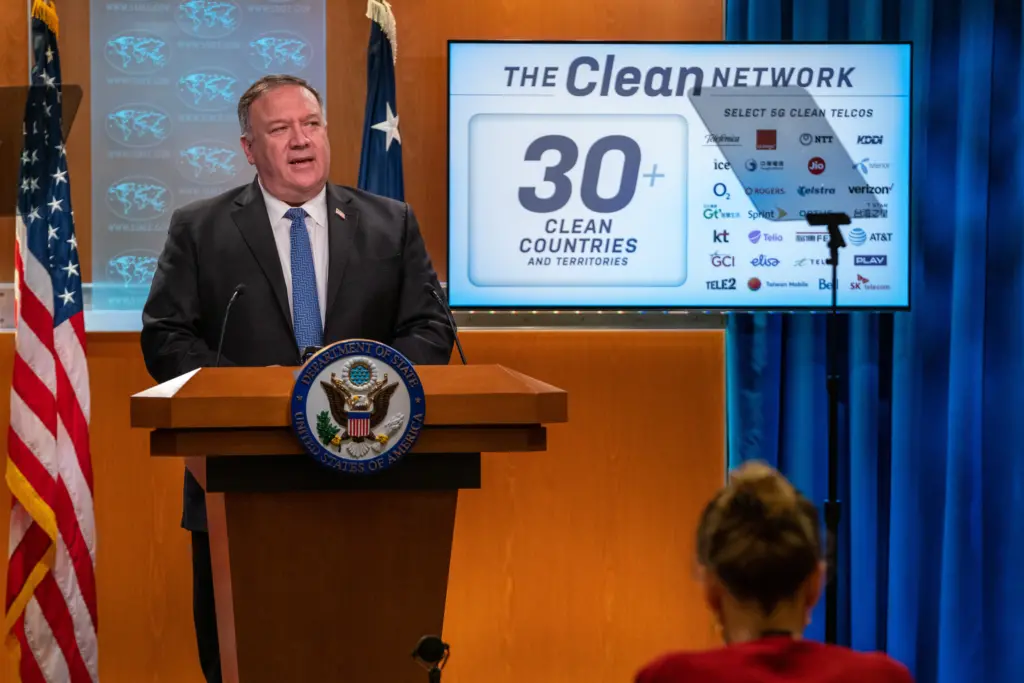

All this is happening as governments the world over increasingly adopt their future model of internet governance—including fundamental decisions as to what level of digital freedom they afford their populaces. These decisions increasingly intersect with great power politics, as the digital arena emerges as a new front in the increasingly competitive relationship between the United States and China, so that internet governance and infrastructure now represent a new axis of geopolitical contention.

The framework of digital sovereignty has become popular in part because it appears to offer governments a set of tools to address peoples’ serious and legitimate concerns about unaccountable large foreign corporations—from telecommunications companies who control the infrastructure of the internet, to the handful of social media companies whose algorithms can influence human behavior and whose business model is based on the collection and commercialization of people’s data.

Yet as governments renegotiate the terms of their power over the functioning of the internet, the result can be an increase in digitally-facilitated repression. Governments the world over have passed new laws mandating data localization, granting them new powers over their citizens’ data and new levers of control over transnational corporations; they have pressured or forced companies to trigger digital shutdowns, becoming complicit in repression; they have demanded content takedowns and other forms of censorship. Companies’ compliance is often predicated on the argument that they must comply with national law—yet this compliance inevitably conflicts with these same companies’ responsibilities to uphold human rights.

The future shape of the internet is actively being decided, and along with it, the extent of our rights to freely access information and express ourselves online. That makes this an issue of fundamental importance for those concerned with freedom of expression, cultural interchange, and our human rights both on and offline.

PEN America’s analysis and engagement on these issues is motivated by our commitment to the PEN Charter, first drafted in 1948, which commits PEN Members to “the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations.”3“PEN International Charter,” PEN International, pen-international.org/who-we-are/the-pen-charter Today, this principle is most embodied by the global internet—the network that allows human beings to communicate across national boundaries and enables information, opinion, and expression to flourish freely. Today this global project is facing increased threat—and demand defending.

Methodology

In producing this report, PEN America draws upon interviews with more than a dozen experts and advocates on internet policy, digital rights, and country-specific issues, as well as from our review of sources including relevant national legislation and regulations, scholarly and news articles, civil society reports, and international norms and standards.

This report begins by identifying and distinguishing between differing conceptions of digital sovereignty, examining the authoritarian origins of the concept alongside its subsequent broader application by governments across the political spectrum, and explaining how the different baseline rights protections within different countries influence how many sovereignty proposals play out in practice. In the second section, we examine how authoritarian countries are pushing for a new model of a more nationalized internet, domestically and on the international stage, threatening to splinter the internet into increasingly disconnected and incompatible networks. We then explore how governments are attempting to re-balance their relationship with the online service providers who control substantial aspects of our digital reality, focusing on how rights-repressive governments specifically have developed or accelerated regulatory tactics to compel or induce corporations to comply with abusive demands. Such tactics, we explain, illustrate how calls for corporate accountability must be thought through with care, to avoid simply handing governments new powers they can use for political ends. Finally, we explain how rising US-China tensions are changing the terms of the debate over global digital regulation, before evaluating calls for a new form of digital democratic multilateralism. We end this report with a call for a global approach to digital regulation that affirms the primacy of human rights and global connectivity, and for a greater corporate commitment to international human rights standards in the face of repressive national dictates.

Section I: Digital Sovereignty, Digital “Deciders,” and the Future of the Internet

At its most basic, the doctrine of digital sovereignty holds that governments should be able to exercise sovereign control over both the infrastructure and the content of the digital realm within their own borders, in order to better serve their national interests.4See generally Julia Pohle and Thorsten Thiel, “Digital Sovereignty,” Internet Policy Review 9, no. 4 (December 17, 2020): policyreview.info/concepts/digital-sovereignty Yet because governments define their national interests so differently, the way this sovereignty is invoked varies vastly.5Julia Pohle and Thorsten Thiel, “Digital Sovereignty,” Internet Policy Review 9, no. 4 (December 17, 2020): policyreview.info/concepts/digital-sovereignty (“Today, the concept of digital sovereignty is being deployed in a number of political and economic arenas, from more centralised and authoritarian countries to liberal democracies. It has acquired a large variety of connotations, variants and changing qualities. Its specific meaning varies according to the different national settings and actor arrangements but also depending on the kind of self-determination these actors emphasise”). Note: While there has been an increasing usage of the term to refer to individual digital sovereignty—that is, an individual person’s sovereignty over their digital data—that usage is less common. Here, unless otherwise specified, PEN America refers to digital sovereignty in terms of the state.

As a doctrine, digital sovereignty suffers from an unfortunate starting point—its earliest proponents have been authoritarian leaders who subscribe to a vision of sovereignty that gives them substantial power to restrict or violate the rights of their own citizens. These leaders have invoked this notion of sovereignty over the digital sphere as a justification for the privileges of state, and as a convenient justification for digital repression. Today, authoritarian governments have not only implemented this framework of digital sovereignty domestically, but—as this report discusses in greater detail—have pushed for it on the global stage.

In recent years, however, many others have begun invoking digital sovereignty: from key leaders within the European Union, who invoke it as a framework for more muscular regulation, to regulators in countries with developing digital economies who argue this sovereignty offers them a shield to defend their citizens and businesses from unaccountable foreign actors. The extent to which these actors are able to re-package digital sovereignty to fit within a democratic and rights-respecting framework, while avoiding the temptation to accrue dangerous or injurious new powers over the digital space, will play a large role in determining the future of the global internet.

The Authoritarian Origins of Digital Sovereignty as a Doctrine

The Chinese government was the first to lay out its framework for digital sovereignty, which it has described as “cyber sovereignty.” In 2010, the Chinese State Council Information Office, the press organ of the country’s chief administrative body, released the white paper “The Internet in China,” declaring that “Within Chinese territory the internet is under the jurisdiction of Chinese sovereignty,” and that all those within China were obligated to “obey the laws and regulations of China and conscientiously protect internet security.”6State Council Information Office of People’s Republic of China (SCIO), “Full Text: White paper on the Internet in China,” China Daily, June 8, 2010, chinadaily.com.cn/china/2010-06/08/content_9950198.htm; see also Min Jiang, “Authoritarian Informationalism: China’s Approach to internet Sovereignty,” SAIS Review of International Affairs 30, no. 3, (2010): 71–89, doi.org/10.1353/sais.2010.0006 In subsequent public pronouncements, government officials have continued to invoke the nation’s “cyber sovereignty” as the overarching framework for their regulatory policy.7E.g. Xinhua, “Lu Wei: Liberty and Order in Cyberspace (Full Text),” China Daily, September 9, 2013, usa.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013-09/09/content_16955871.htm; Rogier Creemers, Paul Triolo, and Graham Webster, “Translation: China’s new top Internet official lays out agenda for Party control online,” New America, September 24, 2018, newamerica.org/cybersecurity-initiative/digichina/blog/translation-chinas-new-top-internet-official-lays-out-agenda-for-party-control-online/

Under this approach, the state is empowered to act as the ultimate gatekeeper for all digital information entering or exiting the country, as well as the manager of all information flows within the country.8Interview with Alena Epifanova, Research Fellow, International Order and Democracy, German Council of Foreign Relations, October 6, 2020 (“the state becomes the main gatekeeper for digital information. The state decides which information will come into the country, and the state is also the main regulator or manager of information flow within the country.”) This empowerment exempts the government from any obligation to ensure the free flow of information across—or even within—national borders, allowing an authoritarian state to place its own prerogatives over its citizens’ rights. Such centralized state control allows the government to hardwire digital censorship and surveillance into the state’s regulatory and technological infrastructure.

This authoritarian framework of digital sovereignty also gives precedence to considerations of national security, treating the free movement of information as inherently hostile and dangerous, and enabling rights-abusive measures in the name of the national interest. As Konstantinos Komaitis, the policy director of the Internet Society, describes it, this conception of digital sovereignty is one that is “predominantly attached to notions of national security and securitization,” or in other words, “all about the right of national governments to supervise, regulate, and censor all electronic content that passes through its borders.”9Konstantinos Komaitis, “Sovereignty Strikes the internet: When Two Don’t Become One,” The Conversation, April 2, 2020, komaitis.org/the-conversation/category/sovereignty

From the beginning, supporters of this view of digital sovereignty have essentially admitted that this formulation explicitly contravenes human rights guarantees. In 2011, member states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO)—a Beijing-initiated intergovernmental grouping that then consisted of China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan10In 2017, India and Pakistan joined the SCO.—submitted to the UN General Assembly a proposed International Code of Conduct for Information Security, an attempt to develop new norms for digital regulation that would have given their view of digital sovereignty the status of an international standard. In the Code, SCO members called for an affirmation that “policy authority for Internet-related public issues is the sovereign right of States, which have rights and responsibilities for international Internet-related public policy issues.”11Sarah McKune, “An Analysis of the International Code of Conduct for Information Security,” The Citizen Lab, accessed May 14, 2021, September 15, 2018, citizenlab.ca/2015/09/international-code-of-conduct The Code—which was not adopted12In 2015, SCO members proposed a largely similar version of the Code, which was similarly not adopted. Sarah McKune, “An Analysis of the International Code of Conduct for Information Security,” The Citizen Lab, accessed May 14, 2021, September 15, 2018, citizenlab.ca/2015/09/international-code-of-conduct—also argued that “rights and freedom to search for, acquire, and disseminate information” was predicated on “complying with relevant national laws and regulations,” a formulation incompatible with human rights law.13Sarah McKune, “An Analysis of the International Code of Conduct for Information Security,” The Citizen Lab, accessed May 14, 2021, September 15, 2018, citizenlab.ca/2015/09/international-code-of-conduct In addition, the Code would have bound states to a pledge not to use the internet to “interfere in the internal affairs of other States,” a digital corollary to the long-standing authoritarian rhetoric that human rights advocacy represents interference in their domestic affairs.14Sarah McKune, “An Analysis of the International Code of Conduct for Information Security,” The Citizen Lab, accessed May 14, 2021, September 15, 2018, citizenlab.ca/2015/09/international-code-of-conduct; see e.g. Yu-Jie Chen, “China’s Challenge to the International Human Rights Regime,” New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 51, no. 4 (Summer 2019): 1179–1222, nyujilp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/NYI403.pdf

The Chinese internet experience, as PEN America documented in its 2018 report Forbidden Feeds, is one circumscribed by centralized state control: the world’s most systemic and sophisticated censorship system, lack of privacy protections from state security services, and advanced filtering capabilities that block or surveil access to much of the global internet behind the country’s Great Firewall.15“Forbidden Feeds: Government Controls on Social Media in China,” PEN America, March 13, 2018, pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/PEN-America_Forbidden-Feeds-report-6.6.18.pdf In its western Xinjiang region, the ruling Chinese Communist Party has pioneered new forms of digitally-assisted repression, wielding digital technologies to sweep up massive amounts of data and using “predictive policing”-style algorithmic analysis to determine which Uyghurs and other members of ethnic or religious minorities to send to the region’s internment camps.16Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian, “Exposed: China’s Operating Manuals for Mass Internment and Arrest by Algorithm,” International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, November 24, 2019, icij.org/investigations/china-cables/exposed-chinas-operating-manuals-for-mass-internment-and-arrest-by-algorithm/; See also American University School of Communication, “The Future of Internet Freedom: Policy, Technology and Emerging Threats,” YouTube, December 7, 2020, accessed May 11, 2021, youtu.be/UL2f4GzYy-c?t=1056 (comments from Xiao Qiang of China Digital Times: “I see China’s well on its way to developing further the digital technology and control apparatus–[or] if you want to call it the surveillance state apparatus–on top of its ideological state apparatus and a repressive state apparatus such as police and military. This is a whole new level of the state-controlled, or state has access to [sic], including all of China’s private businesses, Internet businesses… So what we’re really seeing is China is on its way, heading to, a digital totalitarianism state.”) This imposition of a digital police state is facilitating systematic crimes against humanity and cultural erasure, a dystopia that would have been unimaginable only decades ago, and illustrates the most extreme risks of a digital sphere deployed purely in service of the state.17“China: Big Data Fuels Crackdown in Minority Region,” Human Rights Watch, February 26, 2018, hrw.org/news/2018/02/26/china-big-data-fuels-crackdown-minority-region# Under the authoritarian view of digital sovereignty, employing such technology to facilitate abusive policies is not only permissible, but in furtherance of legitimate government aims.

As this report will examine, China and Russia in particular have taken a leadership role in modeling or propagating this particular model of digital sovereignty, to the point that some observers have begun referring to it as “the China model” of digital regulation,18Valentin Weber, “The Sinicization of Russia’s Cyber Sovereignty Model,” Council on Foreign Relations, April 1, 2020, cfr.org/blog/sinicization-russias-cyber-sovereignty-model while others warn it represents a “digital authoritarianism.”19Leonid Kovachich and Andrei Kolesnikov, “Digital Authoritarianism With Russian Characteristics?,” Carnegie Moscow Center, April 21, 2021, carnegie.ru/2021/04/21/digital-authoritarianism-with-russian-characteristics-pub-84346; Alina Polyakova and Chris Meserole, “Exporting digital authoritarianism: The Russian and Chinese models,” The Brookings Institution, August 2019, 11, brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FP_20190827_digital_authoritarianism_polyakova_meserole.pdf

Governments are Adopting and Adapting New Models of Digital Sovereignty

While the concept of digital sovereignty may have originated with Beijing, other actors have since taken up the term. “Years ago, anyone who was talking about cyber sovereignty was assumed to be affiliated with a top-down, authoritarian or at least autocratic internet governance approach,” said Jason Pielemeier, director for policy and strategy at the Global Network Initiative, a multi-stakeholder initiative on human rights in the telecommunications and internet sector. “That’s no longer true. The fact that the European Union, among others, has come to use this idea of sovereignty to refer to technology governance and regulation has made it harder to rely on this language in a meaningful way to distinguish between authoritarian and democratic approaches.”20Interview with Jason Pielemeier, Director for Policy and Strategy, Global Network Initiative, November 9, 2020.

In the past few years, key decision-makers in the European Union (EU) have broadcasted their intent to develop a ‘third way’ of digital regulation, a framework for digital sovereignty that rejects both the comparatively regulation-free approach of the American model of internet governance, and the state-centered authoritarian model pioneered by China. In 2018, at the UN-affiliated Internet Governance Forum (IGF), French president Emmanuelle Macron called for a “new path” for digital regulation—one he distinguished from the “Californian form of the internet” and the “Chinese internet”—where “governments, along with Internet players, civil societies and all actors are able to regulate properly.”21“IGF 2018 Speech by French President Emmanuel Macron,” Internet Governance Forum, 2018, accessed May 11, 2021, intgovforum.org/multilingual/content/igf-2018-speech-by-french-president-emmanuel-macron At the following IGF, Germany’s Angela Merkel offered similar remarks endorsing of a European framework for digital sovereignty, saying:

“What we have to clarify is, what do we mean when we talk about digital sovereignty . . . As I see it, sovereignty does not mean protectionism. It does not mean that a State body can say this or that information may pass through. That would be censorship . . . We are very well aware of the technological advances and companies that developed them, cannot always just be given a free rein. You have to have guardrails in place.”22“German Chancellor’s Remarks to the IGF 2019,” Internet Governance Forum, November 26, 2019, accessed May 11, 2021, intgovforum.org/multilingual/content/german-chancellors-remarks-to-the-igf-2019. Transcript available at intgovforum.org/multilingual/content/igf-2019-%E2%80%93-day-1-%E2%80%93-convention-hall-ii-%E2%80%93-opening-ceremony

Under the European Union’s envisioned framework, the body acts as an attentive regulator, but stops well short of trying to comprehensively control the internet. Instead, their focus is on technological and economic safeguards from foreign actors and tech companies, rather than on state domination of the internet and what is shared on it.23Carla Hobbs, ed., “Europe’s Digital Sovereignty: From Rulemaker to Superpower in the Age of US-China Rivalry,” European Council on Foreign Relations, July 30, 2020, ecfr.eu/publication/europe_digital_sovereignty_rulemaker_superpower_age_us_china_rivalry/; see also Konstantinos Komaitis, “Sovereignty Strikes the internet: When Two Don’t Become One,” The Conversation, April 2, 2020, komaitis.org/the-conversation/category/sovereignty (distinguishing between European, authoritarian, and Indian approaches to sovereignty). Importantly, the EU’s most aggressive actions to achieve this digital sovereignty are positioned as measures to afford individuals substantial personal control and choice over their data.24Tambiama André Madiega, “Digital Sovereignty for Europe,” European Parliament Think Tank, July 2, 2020, europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/651992/EPRS_BRI(2020)651992_EN.pdf

This envisioned ‘new path’ of European digital sovereignty is influencing EU legislators’ approach to the upcoming Digital Services Act (DSA) and accompanying Digital Markets Act (DMA), two omnibus digital regulatory bills which came before the European Parliament in December 2020. While the Acts are not expected to be finalized until 2022, the DSA would impose new obligations on social media companies to disclose information to regulators, such as how their algorithms and content takedown processes function. Many of these new obligations will only apply to platforms with more than 45 million users—that is to say, the digital behemoths that have become household names, such as Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok.25Billy Perrigo, “How the E.U’s Sweeping New Regulations Against Big Tech Could Have an Impact Beyond Europe,” Time, December 30, 2020, time.com/5921760/europe-digital-services-act-big-tech/ These laws will be far-reaching in their impact, and rights groups have been quick to warn about provisions that could lead to abuse—such as a proposed mandate that internet companies inform law enforcement of “suspicious criminal offences” from their users.26Iverna McGowan, David Nosak, Emma Llanso, “Feedback to the European Commission’s Draft Proposal on the Digital Services Act,” Center for Democracy and Technology, April 1, 2021, cdt.org/insights/feedback-to-the-european-commissions-consultation-on-the-draft-proposal-on-the-digital-services-act/ On the whole, though, these proposals seek primarily to protect and reinforce, rather than curtail, the agency of EU residents online.

The EU’s ability to effectuate its commitment to human rights within its envisioned framework of digital sovereignty may determine the future of the internet. As the former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, David Kaye, has warned, European regulators “could show the way toward rights-oriented regulation” across the globe, or they could instead “give cover to those who want to undermine rights in favor of protections against vague concepts like extremism and national security.”27David Kaye, Speech Police: The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet (New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2019).

This is especially the case because the EU is not the only entity seeking to develop its own model of digital sovereignty. Nations with developing digital economies—such as India, Brazil, Indonesia, Nigeria, and various others—have begun evoking digital sovereignty as an organizing principle for their own regulatory frameworks.28Luca Belli, “BRICS countries to build digital sovereignty,” Open Democracy, November 18, 2019, opendemocracy.net/en/hri-2/brics-countries-build-digital-sovereignty/; PTI, “India’s data must be controlled by Indians: Mukesh Ambani,” mint, January 20, 2019, livemint.com/Companies/QMZDxbCufK3O2dJE4xccyI/Indias-data-must-be-controlled-by-Indians-not-by-global-co.html; Chike Onwuegbuchi, “Stakeholders seek stronger data sovereignty initiatives for Nigeria,” The Guardian Nigeria, January 31, 2021, guardian.ng/technology/stakeholders-seek-stronger-data-sovereignty-initiatives-for-nigeria/; Quentin Velluet, “Can Africa salvage its digital sovereignty?” The Africa Report, April 16, 2021, theafricareport.com/80606/can-africa-salvage-its-digital-sovereignty/; Ed Davies and Stanely Widianto, “Indonesia needs to urgently establish data protection law: minister,” Reuters, November 16, 2019, reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-communications/indonesia-needs-to-urgently-establish-data-protection-law-minister-idUSKBN1XQ0B8 India—which has the world’s second largest internet user base29PTI, “Covid-19 pandemic laid threadbare issue of digital divide: Ravi Shankar Prasad,” The Hindustan Times, April 29, 2021, hindustantimes.com/india-news/covid19-pandemic-laid-threadbare-issue-of-digital-divide-ravi-shankar-prasad-101619667722665.html; Kushe Bahl et al., “Global India: Technology to Transform a Connected Nation,” McKinsey Global Institute, March 2019, 23, mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Business%20Functions/McKinsey%20Digital/Our%20Insights/Digital%20India%20Technology%20to%20transform%20a%20connected%20nation/MGI-Digital-India-Report-April-2019.pdf—has in particular sought to carve out its own doctrine of digital sovereignty, one predicated around active government intervention in the country’s digital development alongside a model of economic and regulatory protectionism aimed at re-orienting the balance of power between itself and foreign internet companies.30PTI, “India’s data must be controlled by Indians: Mukesh Ambani,” mint, January 20, 2019, livemint.com/Companies/QMZDxbCufK3O2dJE4xccyI/Indias-data-must-be-controlled-by-Indians-not-by-global-co.html Indian regulators have argued for an approach where the state plays an active role in enabling the development of local digital platforms that operate as public goods.31Nandan Nilekani, “India’s Inclusive Internet,” Foreign Affairs, August 13, 2018, foreignaffairs.com/articles/asia/2018-08-13/data-people Yet these proposals are gaining traction at the same time that India is experiencing a backslide in its democratic commitments under the Modi government,32“India: Freedom in the World 2021 Country Report,” Freedom House, accessed May 11, 2021, freedomhouse.org/country/india/freedom-world/2021 (downgrading India from “free” to “partly free”). raising the question as to whether Indian officials will use protectionist measures for the people’s benefit, or for their own.33Karan Deep Singh and Paul Mozur, “As Outbreak Rages, India Orders Critical Social Media Posts to Be Taken Down,” The New York Times, May 1, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/04/25/business/india-covid19-twitter-facebook.html This captures a key concern—that regulators may develop frameworks of digital sovereignty that supposedly protect citizens from unaccountable foreign actors but instead place them at greater risk from their own governments.

Today, digital sovereignty is a contested term, with various actors invoking the doctrine to encompass very different concepts of the state’s powers and role. While the authoritarian meaning of such sovereignty is fairly settled, including in its inherent hostility to human rights, governments across the political spectrum now invoke their sovereignty to advance a broad set of digital policies in furtherance of their own national goals.

What is emerging is a global series of differing national (and in the European Union’s case, regional) frameworks for digital sovereignty. Each of these developing frameworks will be deeply shaped by states’ pre-existing commitments to human rights, rule of law, and stable public institutions. “It’s tricky to figure out how to address some of these digital regulatory problems in countries that lack robust checks and balances or mechanisms for independent oversight,” Freedom House’s Adrian Shahbaz affirmed in his conversation with PEN America, “because even if they have the exact same wording as laws as in other countries, they won’t be implemented in the same way.”34Interview with Adrian Shahbaz, Director for Technology and Democracy, Freedom House, November 9, 2020.

For authoritarians and autocrats, the conceptual ambiguity around digital sovereignty and what it entails in practice is politically useful, allowing them to propose rights-abusive laws, rules, and standards on the global stage while hiding behind the conceptual screen of sovereignty also nominally defended by democratic states and blocs. This ambiguity also enables autocratic rulers to depict their own repressive efforts as fundamentally similar to initiatives from established democracies with rule of law and stable institutions. “Authoritarian governments,” as David Kaye warns, “are taking cues from the loose regulatory talk among democracies.”35David Kaye, Speech Police: The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet (New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2019), 113.

As one analysis from the German Council of Foreign Relations puts it, “both Russian and Chinese leadership understand perfectly that [the] idea of censorship is difficult to sell to a global audience. Therefore, they are mimicking the language and terminology used by many European countries,” in order to camouflage the abusive elements of their digital regulatory policies.36Andrei Soldatov, “Security First, Technology Second,” DGAP, March 7, 2019, dgap.org/en/research/publications/security-first-technology-second Alena Epifanova, a researcher with the German Council, made this point in her conversation with PEN America, drawing on the Russian example: “The Russian government actually uses this lack of clarity around sovereignty to their advantage,” she noted, “as it makes it much easier for them to promote their vision of internet governance—where the internet should be state-centered—on the international level.”37Interview with Alena Epifanova, Research Fellow, International Order and Democracy, German Council of Foreign Relations, October 6, 2020.

All this underscores a vital point: the foundation of any democratic framework for digital sovereignty must, by definition, include a commitment to and continuous investment in people’s digital privacy and free speech, along with a system of rule of law and functioning institutions to guarantee these rights in the face of government or corporate power. Any democratic state invoking such sovereignty must foreground these commitments.

Digital Sovereignty as a Rejection of The American Internet Model

Today, the impulse toward greater digital sovereignty is ascendant, in large part, as a result of significant global concerns over the negative consequences of the hands-off ‘American model’ of digital governance, in addition to the outsized control that both the American government and American-based internet titans appear to have over the global internet.

Firstly, there are valid concerns over the lack of democratic accountability for American internet corporations. In the Global South especially, analysts and advocates have argued that Silicon Valley’s domination of the digital economy has been so lopsided that it constitutes a new phenomenon of “digital colonialism,” for which government intervention is not just desirable but necessary.38Michael Kwet, “Digital colonialism is threatening the Global South,” Al Jazeera, March 13, 2019, aljazeera.com/opinions/2019/3/13/digital-colonialism-is-threatening-the-global-south; Jacqueline Hicks, “‘Digital colonialism’: Why some countries want to take back control over their citizens’ data,” Scroll.in, October 2, 2019, scroll.in/article/938733/digital-colonialism-why-some-countries-want-to-take-back-control-over-their-citizens-data; see also David Kaye, Speech Police: The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet (New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2019), 31-32; Sally Adee, “The global internet is Disintegrating. What Comes Next?” BBC, May 14, 2019, bbc.com/future/article/20190514-the-global-internet-is-disintegrating-what-comes-next (“Nations like Zimbabwe and Djibouti, and Uganda, they don’t want to join an internet that’s just a gateway for Google and Facebook” to colonise their digital spaces, [Maria Farrell of Open Rights Group] says.”). Digital sovereignty is being invoked as a countermeasure to this domination.39Jacqueline Hicks, “‘Digital colonialism’: Why some countries want to take control of their peoples’ data,” Mail & Guardian, September 30, 2019, mg.co.za/article/2019-09-30-digital-colonialism-some-countries-want-to-take-control-of-their-peoples-data/

These fears tie into global alarm over the increasingly apparent, often menacing social effects of the business models for some of the world’s largest technology companies—social media and digital advertising platforms in particular. Academic and author Shoshanna Zuboff has forcefully argued that the prevailing model of our digital reality amounts to “surveillance capitalism,” an economic system geared toward the commoditization of people’s personal data.40Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for A Human Future at a New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020).

Secondly, concerns over American intelligence gathering have also fed into the global push for more digital sovereignty. The revelations, exposed in 2013 by Edward Snowden, that US intelligence agencies were engaged in widespread dragnet surveillance of both U.S. and foreign citizens, are almost universally cited as a major impetus for this shift.41Zygmunt Bauman et al., “After Snowden: Rethinking the Impact of Surveillance,” International Political Sociology 8, no. 2 (June 2014): academic.oup.com/ips/article-abstract/8/2/121/1794335?redirectedFrom=fulltext; see also Heikki Heikkilä et al., eds, Journalism and the NSA Revelations: Privacy, Security, and the Press (London: I.B. Tauris, 2017), chap. 8, Google Books, books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=N7qKDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA147&dq=defining+digital+sovereignty&ots=Fbre4KMOP5&sig=CiEKB-yYQEbPaFu-O4sI0NlbXbs#v=onepage&q=defining%20digital%20sovereignty&f=false (“In mainstream media around the world, the issues raised by the NSA scandal . . . provoked debate about the US technological monopoly over global information and communication networks. The large-scale exposure of US intelligence capacity bolstered a strong argument for constructing an alternate model for internet governance, both globally and domestically.”); American University School of Communication, “The Future of Internet Freedom: Policy, Technology and Emerging Threats,” YouTube, December 7, 2020, accessed May 11, 2021, https://youtu.be/UL2f4GzYy-c?t=447 (comments by American University professor Aram Sinnreich: “Back when Secretary of State Hillary Clinton first introduced the term ‘internet freedom’ on the world stage a decade ago, America was kind of seen as this gold standard of openness and transparency and accountability. But beginning with the Snowden leaks in 2013, and following through some of the changes to American technological and cultural diplomacy in the Trump era, I think there’s a lot of mistrust poisoning the international waters.”); Akash Kapur, “The Rising Threat of Digital Nationalism,” The Wall Street Journal, November 1, 2019, wsj.com/articles/the-rising-threat-of-digital-nationalism-11572620577; Sally Adee, “The global internet is Disintegrating. What Comes Next?” BBC, May 14, 2019, bbc.com/future/article/20190514-the-global-internet-is-disintegrating-what-comes-next (“Along with every other expert interviewed for this article, Farrell reiterated how unwise it would be underestimate the ongoing reverberations of the Snowden revelations – especially the extent to which they undermined the decider countries’ trust in the open web.”)

In 2015, PEN America conducted our own global survey of writers across 50 countries, to assess the impact of the Snowden revelations on their willingness to write freely. We concluded then that American mass surveillance had “gravely damaged the United States’ reputation as a haven for free expression at home, and a champion of free expression abroad.”42“Global Chilling: The Impact of Mass Surveillance on International Writers,” PEN America, January 5, 2015, It is no surprise, then, that these surveillance programs have had tangible effects on digital policy, spurring other countries to act defensively—either out of the desire to shield their citizens from unaccountable foreign surveillance or out of national security or power-competition considerations.

The development of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, for example, was deeply influenced by the Snowden disclosures, turbocharging European privacy advocates at a crucial point in the process.43Nikhil Kalyanpur, “Today, a new E.U. law transforms privacy rights for everyone. Without Edward Snowden, it might never have happened.” The Washington Post, May 25, 2018, washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/05/25/today-a-new-eu-law-transforms-privacy-rights-for-everyone-without-edward-snowden-it-might-never-have-happened/; Nikhil Kalyanpur and Abraham Newman, “The MNC-Coalition Paradox: Issue Salience, Foreign Firms, and the General Data Protection Regulation,” Journal of Common Market Studies (January 6, 2019): doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12810 The European Parliamentary Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs was actively investigating the impact of the Snowden disclosures on the rights of EU citizens at exactly the same time that it began evaluating the first formal draft of the regulation.44Hallie Coyne, “The Untold Story of Snowden’s Impact on the GDPR,” Cyber Defense Review (CDR), November 15, 2019, cyberdefensereview.army.mil/Portals/6/Documents/CDR%20Journal%20Articles/Fall%202019/CDR%20V4N2-Fall%202019_COYNE.pdf?ver=2019-11-15-104104-157 The GDPR, adopted in 2016 and becoming enforceable in 2018, created a minimum standard of data protection for all EU internet users, and has become the world’s most significant data protection standard in place today, inspiring other countries—including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Japan and Kenya—to adopt legislation modeled on it.45Ben Wolford, “What is GDPR, the EU’s new data protection law?,” GDPR.eu, accessed April 26, 2021 gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/; Tony Anscombe, “Twelve years later, has GDPR fulfilled its promise?,” WeLiveSecurity, May 25, 2020, https://www.welivesecurity.com/2020/05/25/two-years-later-has-gdpr-fulfilled-its-promise/; David Ruiz, “GDPR: An impact around the world,” MalwareBytesLabs, April 1, 2020, https://blog.malwarebytes.com/privacy-2/2020/04/gdpr-an-impact-around-the-world/; see also Francesca Lucarini, ”The differences between the California Consumer Privacy Act and the GDPR,” Advisera, April 13, 2020, advisera.com/eugdpracademy/blog/2020/04/13/gdpr-vs-ccpa-what-are-the-main-differences/.

In two highly public decisions, the European Court of Justice has ruled that the United States’s privacy protections did not adequately protect Europeans’ data under the GDPR. In 2015, in a case known as the “Schrems decision,” the Court invalidated the “Safe Harbor” arrangement between the US and the EU, which had permitted the transfer of personal data from EU member countries to US-based companies.46Case C-362/14, Maximilian Schrems v Data Protection Commissioner, Judgment of the European Court of Justice (Grand Chamber), 6 October 2015; Viviane Reding, “Digital Sovereignty: Europe at a Crossroads,” European Investment Bank Institute, October 26, 2015, accessed May 11, 2021, institute.eib.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Digital-Sovereignty-Europe-at-a-Crossroads.pdf; Court of Justice of the European Union, “The Court of Justice declares that the Commission’s US Safe Harbour Decision is invalid,” press release, October 6, 2015, curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2015-10/cp150117en.pdf The Court made a similar decision in 2020, known as the “Schrems II decision,” invalidating the subsequent US-EU data-transfer agreement known as the Privacy Shield.47Case C-311/18, Data Protection Commissioner v Maximillian Schrems, Judgement of the Court of Justice of the European Union (Grand Chamber), 16 July 2020; Caitlin Fesnessy, “The ‘Schrems II’ decision: EU-US data transfers in question,” iapp, July 16, 2020, iapp.org/news/a/the-schrems-ii-decision-eu-us-data-transfers-in-question/ In both cases, the Court cited a lack of adequate safeguards preventing US intelligence agencies from accessing personal data held by US-based companies.48Case C-362/14, Maximilian Schrems v Data Protection Commissioner, Judgment of the European Court of Justice (Grand Chamber), 6 October 2015; Case C-311/18, Data Protection Commissioner v Maximillian Schrems, Judgement of the Court of Justice of the European Union (Grand Chamber), 16 July 2020

Authoritarian leaders have also been able to leverage these same concerns to pursue their state-centered framework of digital sovereignty, using the Snowden revelations as justification to seek greater state control over the digital sphere. In Russia, Vladimir Putin has played up fears that the internet is controlled or surveilled by American intelligence agencies. In a 2019 televised interview, for example, Putin warned that the internet is the “creation” of Western intelligence agencies, that they “hear, see and read everything that you are saying and they’re collecting security information.” As a result, he argued, Russia “must create a segment [of the internet] which depends on nobody.”49Andrew Roth, “Russia’s great firewall: is it meant to keep information in – or out?” The Guardian, April 28, 2019, theguardian.com/technology/2019/apr/28/russia-great-firewall-sovereign-internet-bill-keeping-information-in-or-out

“For both the EU and Russia,” says Alena Epifanova, a digital regulations researcher at the German Council on Foreign Relations, “much of the conversation about the need for another model of internet governance originates from the Snowden revelations. The EU said, ‘Okay, we can’t trust our US partners. We aren’t sure where the data of our European users would land.’ Russia had the same concern, but followed a different model—towards more centralized state control of the internet.”50Interview with Alena Epifanova, Research Fellow, International Order and Democracy, German Council of Foreign Relations, October 6, 2020.

The National Security Agency’s (NSA) surveillance program is not the only U.S. policy of the past decade that has prompted some governments to seek out greater digital sovereignty. In March of 2018, Congress passed the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act, or CLOUD Act, which—among other provisions—formalized the ability of American law enforcement authorities to compel user data and content from American companies regardless of where in the world that data is actually stored.51“H.R.4943 – CLOUD Act,” Congress.gov, accessed April 27, 2021, congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/4943 These provisions triggered a new wave of conversation around digital sovereignty, in the name of ensuring the privacy of people’s data in the face of American intelligence agencies. In June 2019, for example, France issued a parliamentary report condemning the CLOUD Act provisions and calling for measures to “restore the sovereignty of France.”52Dan Shefet, “A French Perspective on Extraterritorial Enforcement of U.S. Laws,” The ALI Adviser, December 24, 2019, thealiadviser.org/conflict-of-laws/a-french-perspective-on-extraterritorial-enforcement-of-u-s-laws/

American policymakers, analysts, and rights advocates must be aware of, and responsive to, these concerns, as they participate in the debate over the future of the global internet. It is not enough to respond to rising calls for digital sovereignty by simply insisting on a return to the status quo ante. For too many people, the “American model” of internet governance increasingly represents an unfair playing field for American economic or governance interests.

“Digital Deciders” are Choosing Their Model of Internet Governance

These conversations around sovereignty come at a time when countries across the world and across the political spectrum are actively choosing between different frameworks of digital governance that are on offer, making foundational decisions about what the internet will look like within their borders.

Some analysts point to a large set of digital “digital deciders”, countries that are essentially opting for either a closed or an open internet.53Sally Adee, “The global internet is disintegrating. What comes next?” BBC, May 14, 2019, bbc.com/future/article/20190514-the-global-internet-is-disintegrating-what-comes-next; Robert Morgus, Jocelyn Woolbright, and Justin Sherman, “The Digital Deciders: How a group of often overlooked countries could hold the keys to the future of the global internet,” New America, October 23, 2018, newamerica.org/cybersecurity-initiative/reports/digital-deciders/ Several of these nations are among the world’s most populous and are rising global leaders, like India, Brazil, Indonesia, and Nigeria. Moreover, these digital deciders include more than two dozen countries that the NGO Freedom House categorizes as Partly Free–such as illiberal democracies and countries slowly transitioning away from authoritarian pasts.54There are 29 countries in total that are both listed by New America as “digital deciders” and by Freedom House as “partly free”: Albania, Armenia, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Georgia, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Serbia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, and Ukraine. “The Digital Deciders: How a group of often overlooked countries could hold the keys to the future of the global internet,” New America, October 23, 2018, newamerica.org/cybersecurity-initiative/reports/digital-deciders/; “Countries and Territories,” Freedom House, 2021, accessed May 14, 2021, freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores Former Special Rapporteur David Kaye has warned that it is such countries–the “transitional ones that see-saw between openness and control, that could tip into blossoming democracy or creeping authoritarianism”–that are particularly likely to “borrow” the language of internet regulation and deploy it to rights-injurious ends.55David Kaye, Speech Police: The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet (New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2019). In 2018, researchers from the US-based think tank New America determined, worryingly, that these “digital deciders” are increasingly choosing a more closed internet, not a more open one.56David Kaye, Speech Police: The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet (New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2019).

Recent events may only exacerbate these trends. In the past year alone, for example, the COVID-19 pandemic has served as a useful opportunity—or excuse—for governments to expand their control over the digital realm in the name of safeguarding public health and public order. The International Center for Not-for-Profit Law has identified more than 50 examples of countries introducing or amending laws or policies to criminalize disinformation or otherwise limit free expression in response to the pandemic—including 16 countries on New America’s “digital decider” list57Armenia, Bolivia, Bosnia, Botswana, Colombia, India, Indonesia, Jordan, Kenya, Morocco, Macedonia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Serbia, South Africa, and Thailand.—alongside another 40 other forms of pandemic-related constraints on free expression.58COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker, International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), and European Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ECNL), icnl.org/covid19tracker/?location=&issue=4,9&date=&type=1,2,3,4 The substantial majority of these new policies and new constraints touch upon the digital sphere, with many such policies seeking to criminalize or otherwise punish digital “misinformation” about the pandemic.59COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker, International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), and European Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ECNL), icnl.org/covid19tracker/?location=&issue=4,9&date=&type=1,2,3,4; see also Justin Sherman, “Covid Is Accelerating a Global Censorship Crisis,” Wired, August 30, 2020, wired.com/story/opinion-covid-is-accelerating-a-global-censorship-crisis/ As PEN America has recently noted in its Freedom to Write Index review of the past year, these laws pose an obvious threat to freedom of expression, by granting officials broad new powers to police speech that can easily bleed into repression.60Karin Deutsch Karlekar et al., “Freedom to Write Index 2020,” PEN America, April 21, 2021, pen.org/report/freedom-to-write-index-2020/ Digital deciders are hardly alone in facing the impulse to respond to issues of genuine social concern with a heavy governmental hand and cynical political self-interest. But they do so at a time when their governments are making broader decisions regarding the architecture of their digital future.

Meanwhile, champions of the authoritarian vision of digital sovereignty are actively nudging digital deciders toward more closed digital spheres. In Eurasia, at least nine of Russia’s neighboring states have adopted technical or legal aspects of Russia’s internet surveillance structure, while Russian companies have exported the Russian government’s internet surveillance system, known as SORM, to telecom companies in the Middle East and Latin America.61Chris Meserole and Alina Polyakova, “Exporting digital authoritarianism: The Russian and Chinese models,” The Brookings Institution, accessed May 13, 2021, brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FP_20190827_digital_authoritarianism_polyakova_meserole.pdf; Jaclyn A. Kerr, “Information, Security, and Authoritarian Stability: Internet Policy Diffusion and Coordination in the Former Soviet Region,” International Journal of Communication 12, (September 18, 2018): 3814-3834, ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/8542/2460 Meanwhile, China’s Xi Jinping has offered up Beijing’s model of internet governance to other countries as an example of how they can “speed up their development while preserving their independence,”62“China’s Approach to Global Governance,” Council on Foreign Relations, accessed April 27, 2021, cfr.org/china-global-governance/ a description that will appeal to digital deciders—and one that is conspicuously silent about the human rights implications of such a model.

Beijing’s most powerful mechanism for exporting its model of digital governance has been its Belt and Road Initiative, the largest infrastructure development program in the world. As part of this Initiative, Beijing has created what it terms a “Digital Silk Road,” an extensive international development and technology-sharing program.63“Assessing China’s Digital Silk Road Initiative,” Council on Foreign Relations, accessed April 27, 2021, cfr.org/china-digital-silk-road/ Under this program, China has entered into bilateral relationships with an estimated 40 other countries, primarily developing economies that are still building out their digital infrastructure and their digital policies.64“Assessing China’s Digital Silk Road Initiative,” Council on Foreign Relations, accessed April 27, 2021, cfr.org/china-digital-silk-road/; See also Alan Weedon and Samuel Yang, “China trumpets tech power at 6th World Internet Conference, signalling a ‘digital arms race’,” ABC News, October 22, 2019, abc.net.au/news/2019-10-23/sixth-world-internet-conference-china-wuzhen/11623426

This Digital Silk Road enables Beijing to accelerate its exportation of technology that comes with China’s model of digital governance pre-baked into the formula.65“Assessing China’s Digital Silk Road Initiative,” Council on Foreign Relations, accessed April 27, 2021, cfr.org/china-digital-silk-road/; See also Alan Weedon and Samuel Yang, “China trumpets tech power at 6th World Internet Conference, signalling a ‘digital arms race’,” ABC News, October 22, 2019, abc.net.au/news/2019-10-23/sixth-world-internet-conference-china-wuzhen/11623426 This includes internet infrastructure that enables other countries to recreate substantial aspects of China’s Great Firewall, and grants governments new powers of censorship and surveillance. Maria Farrell, former director of the UK-based NGO Open Rights Group, has described the Digital Silk Road as offering a “plug-and-play” internet that gives digital decider countries an option for developing their national internet infrastructure without committing to an open internet. As she puts it, “What China has done is put together a whole suite of not just technology, but information systems, censorship training, and model laws for surveillance. It’s the full kit, and the laws, and the training, to execute a Chinese version of the internet.”66Sally Adee, “The global internet is Disintegrating. What Comes Next?” BBC, May 14, 2019, bbc.com/future/article/20190514-the-global-internet-is-disintegrating-what-comes-next

Adrian Shahbaz, Director for Democracy and Technology at Freedom House, has closely followed Beijing’s efforts in this area. Shahbaz warned in his conversation with PEN America that “we are approaching a stage where the Chinese model of internet governance is looking more appealing to certain states, particularly as they perceive the unregulated internet as a threat to either social stability or regime survival.”67Interview with Adrian Shahbaz, Director for Technology and Democracy, Freedom House, November 9, 2020. It falls upon those who are committed to the vision of an open, global, and human rights respecting internet to offer a contrasting agenda to which digital deciders can rally.

Special Section: Digital Sovereignty as Control over Data

One of the primary digital sovereignty concerns of governments is over their residents’ data. Such data represents an economic and analytic goldmine, leading some commentators to declare that “Data is the new oil.”68Adeola Adesina, “Data is the New Oil,” Medium.com, November 13, 2018 medium.com/@adeolaadesina/data-is-the-new-oil-2947ed8804f6: Kiran Bhageshpur, “Data Is The New Oil — And That’s A Good Thing,” Forbes, November 15, 2019, forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2019/11/15/data-is-the-new-oil-and-thats-a-good-thing/#669f22707304; Joris Toonders, “Data Is the New Oil of the Digital Economy,” Papers Owl https://papersowl.com/discover/data-is-the-new-oil-of-the-digital-economy; see also Lindsay P. Gorman, “A Future Internet for Democracies: Contesting China’s Dominance in 5G, 6G, and the Internet-of-Everything,” Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States, October 27, 2020, securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Future-Internet.pdf Increasingly, countries around the world are insisting on sovereign control over this data: how it is used, who has access to it, and where it is stored or allowed to travel.

As a result, governments have enacted a wave of laws and regulations implementing data localization (or “data residency”) requirements. Broadly, this means mandating that the data generated by users within their country be stored within national borders. Internet experts have long warned that mandatory localization efforts will contribute to internet fragmentation and impede the openness and accessibility of the global internet, by creating new barriers to transnational data flows.69See e.g. Anupam Chander et al., “Exploring International Data Flow Governance,” World Economic Forum, 22, December 2019, weforum.org/docs/WEF_Trade_Policy_Data_Flows_Report.pdf; “Internet Way of Networking Use Case: Data Localization,” Internet Society, September 30, 2020, internetsociety.org/resources/doc/2020/internet-impact-assessment-toolkit/use-case-data-localization/ Yet in the past few years alone, more than 70 countries have passed or amended their laws to include some form of data localization.70“Global Data Governance – Part One: Emerging Data Governance Practices,” Foreign Policy, May 13, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/13/data-governance-privacy-internet-regulation-localization-global-technology-power-map/

Data localization mandates that affect people’s personal data, specifically, raise substantial and systemic human rights concerns because they ensure that such data is kept within the jurisdictional reach of their national law enforcement and state security services—potentially weaponizing it as a tool for repression. If the country demanding the localization of data has an independent judiciary, rule of law, and enshrined privacy rights, then the potential adverse human rights impacts of such data localization may be lessened—although not necessarily eliminated.71See generally Allie Funk, Andrea Hackl, and Adrian Shahbaz, “User Privacy or Cyber Sovereignty: Assessing the Human Rights Implications of Data Localization,” Freedom House, July 2020, freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/user-privacy-or-cyber-sovereignty In countries that do not have a strong legal framework for rights protection, the risks are heightened.

This is particularly the case for governments that criminalize peaceful dissent or otherwise suppress freedom of expression—making these databases potential treasure troves for the discovery of “crimes” involving dissenting speech or opinion. Even access to other forms of data—when and where a certain picture was taken, who uses their internet during a religious holiday and who doesn’t, who were the last five people the activist messaged before their arrest—are potent tools for surveillance and repression. Freedom House, which produced a major analysis of data localization’s human rights effects in 2020, concluded that it was no coincidence that “Some of the most stringent data localization requirements can be found in countries with poor human rights records and restrictive information environments.”72Allie Funk, Andrea Hackl, and Adrian Shahbaz, “User Privacy or Cyber Sovereignty: Assessing the Human Rights Implications of Data Localization,” Freedom House, July 2020, freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/user-privacy-or-cyber-sovereignty; see also Alexander Plaum, “The impact of forced data localisation on fundamental rights,” Access Now, June 4, 2014, accessed May 11, 2021, accessnow.org/the-impact-of-forced-data-localisation-on-fundamental-rights/

Yet these risks are not limited to authoritarian governments alone. “The core issue determining the status of people’s digital rights is the laws and regulations that guarantee people’s privacy rights and the enforceability of those laws and regulations,” Megha Rajagopalan, a tech reporter for Buzzfeed, told PEN America. “And the current status quo is that the majority of countries around the world have not developed laws and regulations that are sufficient to safeguard people’s privacy rights and the rights to free speech.”73Interview with Megha Rajagopalan, International Correspondent, Buzzfeed News, November 11, 2020.

Data localization regulations may also grant governments further powers that may enable abuse—for example, the ability to put pressure on the companies hosting their data within the country to comply with other demands (a phenomenon we examine further in Section III of this report), the ability to cut off access to the data from outside the country, or the ability to funnel data streams through local service providers, providing yet another access point for government surveillance. Some data localization mandates also seek to undermine the efficacy of encryption, by either compelling companies to store encryption keys within the country (as is the case in China),74Samm Sacks, “Data Security and U.S.-China Tech Entanglement,” Lawfare, April 2, 2020, lawfareblog.com/data-security-and-us-china-tech-entanglement or mandating that companies maintain the local data in an unencrypted form (as Pakistan has recently imposed).75Asad Hashim, “Pakistan to ‘review’ controversial internet censorship rules,” Al Jazeera, January 26, 2021, aljazeera.com/news/2021/1/26/pakistani-government-says-will-review-internet-censorship-rules

Whatever the impacts, the motivations for data localization run the gamut: from ensuring residents’ digital privacy from foreign governments , as a form of economic protectionism to advantage local technology companies that can more easily develop local data centers or access datasets, to facilitate law enforcement access to data, or under national security rationales.76Ethan Loufield and Shweta Vashisht, “Data Globalization vs. Data Localization,” Center for Financial Inclusion, February 6, 2020, accessed May 12, 2021, centerforfinancialinclusion.org/data-globalization-vs-data-localization The motivations of ‘law enforcement access’ and ‘national security’ raise obvious red flags for any human rights-minded observer, but government officials can also easily publicly suggest one rationale while downplaying another.77Allie Funk, Andrea Hackl, and Adrian Shahbaz, “User Privacy or Cyber Sovereignty: Assessing the Human Rights Implications of Data Localization,” Freedom House, July 2020, freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/user-privacy-or-cyber-sovereignty (“National security interests often co-opt arguments for greater data privacy to justify an expansion of censorship and surveillance powers.”)

‘Gbenga Sesan, Executive Director of the digital advocacy group Paradigm Initiative, gave PEN America an example of how this dynamic has played out in the data localization conversations in sub-Saharan Africa. “Some of the push for data localization has been from the technology private sector, with companies saying to their governments, ‘Google and Facebook are eating our lunch. Why don’t we have some protectionism? If we store data locally, then these companies will have to work with us local players.’ So that’s one conversation. But the second conversation is between security officials and their government higher-ups, saying ‘if we store the data here, we can get a back door to that data.’ And when you look at the trends in this conversation [around data localization], and you look at the countries that are talking about it–you look at Kenya, South Sudan, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Nigeria, to mention some examples–there are only one or two countries where the conversation is not about governmental control.”78Interview with ‘Gbenga Sesan, Executive Director, Paradigm Initiative, February 23, 2021.

In sum, personal data localization mandates—regardless of whether they are motivated by valid sovereign interests or by anti-democratic or repressive machinations—inevitably open the door to new possibilities for governmental abuse. What is sorely needed is a global approach to the hosting of data that insists on all countries meeting human rights standards for the protection and privacy of such data, rather than one which carves up this data among national jurisdictions. As Freedom House’s Adrian Shahbaz summarized, “The framing around data privacy shouldn’t be around where data is physically located, but rather, whether it’s stored securely and protected from government surveillance and corporate malfeasance.”79Interview with Adrian Shahbaz, Director for Technology and Democracy, Freedom House, November 9, 2020.

Section II: Government Efforts to Undermine the Global Internet

Perhaps the most world-changing attribute of the internet is that it is global–a person can travel across the world and still read their emails, visit websites, and have fundamentally the same online experience. This is an oversimplification, of course: national laws may affect what websites you can visit, or which online speech is censored before you have the chance to view it. Yet the global internet can still be conceived of, broadly, as a unitary project.

This is due, first and foremost, to the fact that the internet is designed to be globally interoperable—with shared foundational technical protocols making it possible for any device, anywhere, to connect to the internet and digitally interact with each other.80Bennett Cyphers and Cory Doctorow, “A Legislative Path to an Interoperable Internet,” Electronic Frontiers Foundation, July 28, 2020, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/07/legislative-path-interoperable-internet; Becky Chao and Ross Schulman, “Promoting Platform Interoperability,” New America, las updated May 13, 2020, https://www.newamerica.org/oti/reports/promoting-platform-interoperability/interoperability-is-fundamental-to-the-internet/ This interoperability underlies the internet as a place where cultures connect, where ideas and identities and freedoms that would not otherwise be possible become so, and where the “unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations”81“PEN International Charter,” PEN International, pen-international.org/who-we-are/the-pen-charter can be a day to day lived reality for billions. Yet this global interoperability is increasingly threatened, by governments working to either enable themselves to separate from the global internet, or to take over the foundational underpinnings which render the global internet interoperable.

The Authoritarian Pursuit of a National Internet

National internets—in which the domestic populace is cut off or largely removed from access to the global internet—have traditionally been understood as exceptions in an increasingly connected world. Apart from China, countries that had cut themselves off from the World Wide Web prior to the last decade included only North Korea, Cuba, and pre-2011 Myanmar.82Ronald Deibert et al., eds., Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering, (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008), MIT Press Direct, direct.mit.edu/books/book/2312/Access-DeniedThe-Practice-and-Policy-of-Global; Max Fisher, “Yes, North Korea has the internet. Here’s what it looks like.” Vox, March 19, 2015, vox.com/2014/12/22/7435625/north-korea-internet; Nancy Scola, “Wait, Cuba Has its Own Internet?” The Washington Post, December 19, 2014, washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2014/12/19/wait-cuba-has-its-own-internet/ Today however, Russia and Iran are pioneering new models for internet nationalization, laying the legal and technical groundwork for independent, centrally-controlled, and nationalized internets. In its ultimate expression, which both countries are actively working toward, this nationalized internet would allow their governments to sever the country’s domestic internet from the global one. Russia and Iran’s efforts have major implications for the future, in part because each of these efforts may provide a blueprint for other governments looking to do the same.

Under President Putin, Russia has aggressively pursued an authoritarian set of digital sovereignty policies over the past decade.83See e.g. Andrei Soldatov, “Security First, Technology Second: Putin Tightens his Grip on Russia’s Internet –with China’s Help,” DGAPkompakt, March 2019, dgap.org/system/files/article_pdfs/2019-03-dgapkompakt.pdf These efforts include the creation of a country-wide online content filtering system in 2012;84See e.g. Andrei Soldatov, “Security First, Technology Second: Putin Tightens his Grip on Russia’s Internet –with China’s Help,” DGAPkompakt, March 2019, dgap.org/system/files/article_pdfs/2019-03-dgapkompakt.pdf the ongoing development of a Russian surveillance ‘back door’ to the internet known as the System of Operative-Search Measures, or SORM–originally modeled off of KGB wiretapping technology;85See e.g. Chris Meserole and Alina Polyakova, “Exporting digital authoritarianism: The Russian and Chinese models,” The Brookings Institution, accessed May 13, 2021, brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FP_20190827_digital_authoritarianism_polyakova_meserole.pdf and the passage of the “Yarovaya Law” in 2016, which imposed new requirements on technology companies to collect and store data within Russia, mandated that online service providers provide security services with backdoor access to encrypted content, and compelled providers to provide law enforcement access to data upon request.86See e.g. Matthew Bodner, “What Russia’s New Draconian Data Laws Mean for Users,” The Moscow Times, July 13, 2016, themoscowtimes.com/2016/07/13/what-russias-new-draconian-data-laws-mean-for-users-a54552; See also: Andrei Soldatov, “Security First, Technology Second: Putin Tightens his Grip on Russia’s Internet –with China’s Help,” DGAPkompakt, March 2019, dgap.org/system/files/article_pdfs/2019-03-dgapkompakt.pdf; Chris Meserole and Alina Polyakova, “Exporting digital authoritarianism: The Russian and Chinese models,” The Brookings Institution, accessed May 13, 2021, brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FP_20190827_digital_authoritarianism_polyakova_meserole.pdf. The law took effect in 2018: “Russia’s ‘Big Brother’ Law Enters Into Force,” The Moscow Times, July 1, 2018, themoscowtimes.com/2018/07/01/russias-big-brother-law-enters-into-force-a62066 In 2018, Russian regulators attempted, largely unsuccessfully, to block the popular encrypted messaging program Telegram, after the company refused to hand over its encryption keys to the government.87Michael Grothhaus, “Russian court orders ban on secure messaging app Telegram,” Fast Company, April 13, 2018, fastcompany.com/40558676/russian-court-orders-ban-on-secure-messaging-app-telegram; See also Leonid Bershidsky, “Russian Censor Gets Help From Amazon and Google,” Bloomberg, May 3, 2018 bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2018-05-03/telegram-block-gets-help-from-google-and-amazon; Matt Burgess, “This is why Russia’s attempts to block Telegram have failed,” Wired, April 28, 2018, wired.co.uk/article/telegram-in-russia-blocked-web-app-ban-facebook-twitter-google; Sean Gallagher, “Google disables “domain fronting” capability used to evade censors,” Arstechnica, April 19, 2018, arstechnica.com/information-technology/2018/04/google-disables-domain-fronting-capability-used-to-evade-censors/

Russia’s most significant step in expanding its control over the internet came in 2019, with the passage of its Sovereign Internet Law legalizing the government’s reach into nearly every corner of its domestic internet infrastructure. Some observers have analogized this law as a step towards Russia’s own “Great Firewall.”88Andrew Roth, “Russia’s great firewall: is it meant to keep information in – or out?” The Guardian, April 28, 2019, theguardian.com/technology/2019/apr/28/russia-great-firewall-sovereign-internet-bill-keeping-information-in-or-out Technically a series of amendments to preexisting regulations, the Sovereign Internet Law both creates a legal framework and mandates construction of the technological infrastructure for the government to close down Russians’ access to the global internet.89“Russia: New Law Expands Government Control Online,” Human Rights Watch, October 31, 2019, hrw.org/news/2019/10/31/russia-new-law-expands-government-control-online#; Alena Epifanova, “Deciphering Russia’s Sovereign internet Law: Tightening Control and Accelerating the Splinternet,” German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP), January 16, 2020, dgap.org/en/research/publications/deciphering-russias-sovereign-internet-law It provides the legal basis for the Russian government to route web traffic through state-controlled chokepoints; censor content without due process or public disclosure; block popular encrypted messaging apps like Telegram; and create a ‘kill switch’ that could shut off internet traffic into and out of the country whenever the government deems necessary.90“Russia: New Law Expands Government Control Online,” Human Rights Watch, October 31, 2019, hrw.org/news/2019/10/31/russia-new-law-expands-government-control-online#; Alena Epifanova, “Deciphering Russia’s Sovereign internet Law: Tightening Control and Accelerating the Splinternet,” German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP), January 16, 2020, dgap.org/en/research/publications/deciphering-russias-sovereign-internet-law

The Sovereign Internet Law even enables the construction of a new infrastructure for a separate, national, Domain Name System (DNS), a foundational element of internet architecture that is managed globally by the non-governmental Internet Corporation on Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). This separate DNS infrastructure would lay down foundational protocols for a Russian internet that would be technologically separate from the global internet.91“Russia: New Law Expands Government Control Online,” Human Rights Watch, October 31, 2019, hrw.org/news/2019/10/31/russia-new-law-expands-government-control-online#; Alena Epifanova, “Deciphering Russia’s Sovereign internet Law: Tightening Control and Accelerating the Splinternet,” German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP), January 16, 2020, dgap.org/en/research/publications/deciphering-russias-sovereign-internet-law