No Excuse for Abuse

What Social Media Companies Can Do Now to Combat Online Harassment and Empower Users

Key Findings

Online abuse strains the mental and physical health of its targets, and can cause people to self-censor, avoid certain subjects, or leave their professions altogether.

When online abuse drives women, LGBTQIA+, BIPOC, and minority writers and journalists to leave industries that are predominantly male, heteronormative, and white, public discourse becomes less open and less free.

Social media platforms should adopt proactive measures that empower users to reduce risk and minimize exposure, reactive measures that facilitate response and alleviate harm; and accountability measures that deter abusive behavior.

PEN America Experts:

Director, Digital Safety and Free Expression

Senior Advisor, Online Abuse Defense Program

Introduction

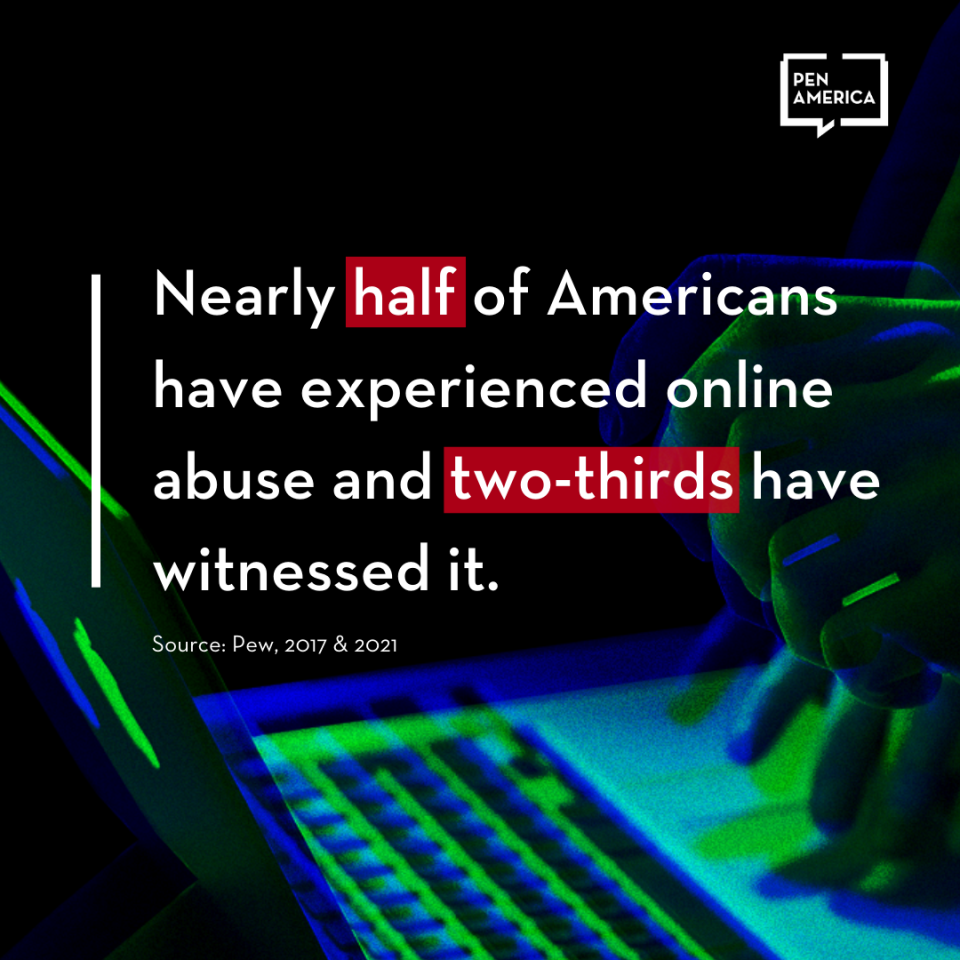

Online abuse—from violent threats and hateful slurs to sexual harassment, impersonation, and doxing—is a pervasive and growing problem.1PEN America defines online abuse as the “severe or pervasive targeting of an individual or group online with harmful behavior.” PEN America defines doxing as the “publishing of sensitive personal information online—including home address, email, phone number, social security number, photos, etc.—to harass, intimidate, extort, stalk, or steal the identity of a target.” “Defining ‘Online Abuse’: A Glossary of Terms,” Online Harassment Field Manual, accessed January 2021, onlineharassmentfieldmanual.pen.org/defining-online-harassment-a-glossary-of-terms/ Nearly half of Americans report having experienced it,2“Online Hate and Harassment Report: The American Experience 2020,” ADL, June 2020, adl.org/online-hate-2020; see also Emily A. Vogels, “The State of Online Harassment,” Pew Research Center, January 13, 2021, pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/ and two-thirds say they have witnessed it.3Maeve Duggan, “Online Harassment 2017: Witnessing Online Harassment,” Pew Research Center, July 11, 2017, www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/07/11/witnessing-online-harassment/ But not everyone is subjected to the same degree of harassment. Certain groups are disproportionately targeted for their identity and profession. Because writers and journalists conduct so much of their work online and in public, they are especially susceptible to such harassment.4Michelle P. Ferrier, “Attacks and Harassment: The Impact on Female Journalists and Their Reporting (Rep.),” IWMF/TrollBusters, 2018, iwmf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Attacks-and-Harassment.pdf; “Why journalists use social media,” NewsLab, 2018, newslab.org/journalists-use-social-media/#:~:text=The%20researchers%20found%20that%20eight,media%20in%20their%20daily%20work.&text=About%2073%20percent%20of%20the,there%20is%20any%20breaking%20news Among writers and journalists, the most targeted are those who identify as women, BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and/or members of religious or ethnic minorities.5For impact on female journalists internationally, see Ibid. and Julie Posetti et al., “Online violence Against Women Journalists: A Global Snapshot of Incidence and Impacts,” UNESCO, December 1 2020, icfj.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/UNESCO%20Online%20Violence%20Against%20Women%20Journalists%20-%20A%20Global%20Snapshot%20Dec9pm.pdf; For impact on women and gender nonconforming journalists in the U.S. and Canada, see: ; see also Lucy Westcott, “‘The threats follow us home’: Survey details risks for female journalists in U.S., Canada,” CPJ, September 4, 2019, cpj.org/2019/09/canada-usa-female-journalist-safety-online-harassment-survey/; For impact on women of color, including journalists, see: “Troll Patrol Findings,” Amnesty International, 2018, decoders.amnesty.org/projects/troll-patrol/findings Online abuse is intended to intimidate and censor. When voices are silenced and expression is chilled, public discourse suffers. By reducing the harmful impact of online harassment, platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram can ensure that social media becomes more open and equitable for all users. In this report, PEN America proposes concrete, actionable changes that social media companies can and should make immediately to the design of their platforms to protect people from online abuse—without jeopardizing free expression.

If you’re going to be a journalist, there is an expectation to be on social media. I feel that I have no choice. The number of followers is something employers look at. This is unfair, because there are not a lot of resources to protect you. No matter what I say about race, there will be some blowback. Even if I say nothing, when my colleague who is a white man takes positions on racism, trolls come after me on social media.

Jami Floyd, senior editor of the Justice and Race Unit at New York Public Radio

The devastating impact of online abuse

Writers and journalists are caught in an increasingly untenable double bind. They often depend on social media platforms—especially Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram—to conduct research, connect with sources, keep up with breaking news, promote and publish their stories, and secure professional opportunities.6“Why journalists use social media,” NewsLab, 2018, newslab.org/journalists-use-social-media/#:~:text=The%20researchers%20found%20that%20eight,media%20in%20their%20daily%20work.&text=About%2073%20percent%20of%20the,there%20is%20any%20breaking%20news; “2017 Global Social Journalism Study,” Cision, accessed February 19, 2021, cision.com/content/dam/cision/Resources/white-papers/SJS_Interactive_Final2.pdf Yet their visibility and the very nature of their work—in challenging the status quo, holding the powerful accountable, and sharing analysis and opinions—can make them lightning rods for online abuse, especially if they belong to frequently targeted groups and/or if they cover beats such as feminism, politics, or race.7Gina Massulo Chen et al., “‘You really have to have thick skin’: A cross-cultural perspective on how online harassment influences female journalists,” Journalism 21, no. 7 (2018), doi.org/10.1177/1464884918768500“If you’re going to be a journalist, there is an expectation to be on social media. I feel that I have no choice. The number of followers is something employers look at,” says Jami Floyd, senior editor of the Justice and Race Unit at New York Public Radio. “This is unfair, because there are not a lot of resources to protect you. No matter what I say about race, there will be some blowback. Even if I say nothing, when my colleague who is a white man takes positions on racism, trolls come after me on social media.”8Jami Floyd, interview with PEN America, June 6, 2020.

A 2018 study conducted by TrollBusters and the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) found that 63 percent of women media workers in the United States have been threatened or harassed online at least once,9Michelle P. Ferrier, “Attacks and Harassment: The Impact on Female Journalists and Their Reporting,” IWMF/TrollBusters, 2018, iwmf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Attacks-and-Harassment.pdf; see also Lucy Westcott, “‘The threats follow us home’: Survey details risks for female journalists in U.S., Canada,” CPJ, September 4, 2019, cpj.org/2019/09/canada-usa-female-journalist-safety-online-harassment-survey/; for global stats, see also: Julie Posetti et al., “Online violence Against Women Journalists: A Global Snapshot of Incidence and Impacts,” UNESCO, December 1 2020, icfj.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/UNESCO%20Online%20Violence%20Against%20Women%20Journalists%20-%20A%20Global%20Snapshot%20Dec9pm.pdf; (73 percent of the female journalists who responded to this global survey said they had experienced online abuse, harassment, threats and attacks.) a number significantly higher than the national average for the general population.10Emily A. Vogels, “The State of Online Harassment,” Pew Research Center, January 13, 2021, pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/ Often women are targeted in direct response to their identities.11Women cited disproportionate levels of harassment, including more than three times the gender-based harassment experienced by men (37 percent versus 12 percent). “Online Hate and Harassment Report: The American Experience 2020,” ADL, June 2020, adl.org/online-hate-2020 “I am often harassed online when I cover white nationalism and anti-Semitism, especially in politics or when perpetrated by state actors,” says Laura E. Adkins, a journalist and opinion editor of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “My face has even been photoshopped into an image of Jews dying in the gas chambers.”12Laura E. Adkins, interview with PEN America, June 15, 2020. Individuals at the intersection of multiple identities, especially women of color, experience the most abuse—by far.13A 2018 study from Amnesty International found that women of color—Black, Asian, Hispanic, and mixed-race women—are 34 percent more likely to be mentioned in abusive or problematic tweets than white women; Black women, specifically, are 84 percent more likely than white women to be mentioned in abusive or problematic tweets. “Troll Patrol Findings,” Amnesty International, 2018, decoders.amnesty.org/projects/troll-patrol/findings

The consequences are dire. Online abuse strains the mental and physical health of its targets and can lead to stress, anxiety, fear, and depression.14Michelle P. Ferrier, “Attacks and Harassment: The Impact on Female Journalists and Their Reporting,” IWMF/TrollBusters, 2018, iwmf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Attacks-and-Harassment.pdf; Lucy Westcott, “‘The Threats Follow Us Home’: Survey Details Risks for Female Journalists in U.S., Canada,” Committee to Protect Journalists, September 4, 2019, cpj.org/2019/09/canada-usa-female-journalist-safety-online-harassment-survey/ In extreme cases, it can escalate to physical violence and even murder.15According to a recent global study of female journalists conducted by UNESCO and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), 20 percent of respondents reported that the attacks they experienced in the physical world were directly connected with online abuse. Julie Posetti et al., “Online violence Against Women Journalists: A Global Snapshot of Incidence and Impacts,” UNESCO, December 1 2020, icfj.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/UNESCO%20Online%20Violence%20Against%20Women%20Journalists%20-%20A%20Global%20Snapshot%20Dec9pm.pdf; The Committee to Protect Journalists has reported that 40 percent of journalists who are murdered receive threats, including online, before they are killed. Elisabeth Witchel, “Getting Away with Murder,” CPJ, October 31, 2017, cpj.org/reports/2017/10/impunity-index-getting-away-with-murder-killed-justice-2/ Because the risks to health and safety are very real, online abuse has forced some people to censor themselves, avoid certain subjects, step away from social media,16“Online Harassment Survey: Key Findings,” PEN America, accessed September 2020, pen.org/online-harassment-survey-key-findings/; Mark Lieberman, “A growing group of journalists has cut back on Twitter, or abandoned it entirely,” Poynter Institute, October 9, 2020, poynter.org/reporting-editing/2020/a-growing-group-of-journalists-has-cut-back-on-twitter-or-abandoned-it-entirely/?utm_source=Weekly+Lab+email+list&utm_campaign=0862b74d55-weeklylabemail&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_8a261fca99-0862b74d55-396347589; “Measuring the prevalence of online violence against women,” The Economist Intelligence Unit, accessed March 2021, onlineviolencewomen.eiu.com/ or leave their professions altogether.17Michelle P. Ferrier, “Attacks and Harassment: The Impact on Female Journalists and Their Reporting,” IWMF/TrollBusters, 2018, iwmf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Attacks-and-Harassment.pdf Dr. Michelle Ferrier, a journalist who founded the anti-harassment nonprofit TrollBusters after facing relentless racist and sexist abuse online, recalls: “I went to management. I went to the police. I went to the FBI, CIA. The Committee to Protect Journalists took my case to the Department of Justice. Nothing changed. But I did. I changed as a person. I became angrier. More wary and withdrawn. I had police patrolling my neighborhood. I quit my job to protect my family and young children.”18“About us—TrollBusters: Offering Pest Control for Journalists,” TrollBusters, June 2020, yoursosteam.wordpress.com/about/

When online abuse drives women, LGBTQIA+, BIPOC, and minority writers and journalists to leave industries that are predominantly male, heteronormative, and white, public discourse becomes less open and less free.19“What Online Harassment Tells Us About Our Newsrooms: From Individuals to Institutions,” Women’s Media Center, 2020, womensmediacenter.com/assets/site/reports/what-online-harassment-tells-us-about-our-newsrooms-from-individuals-to-institutions-a-womens-media-center-report/WMC-Report-What-Online-Harassment_Tells_Us_About_Our_Newsrooms.pdf Individual harms have systemic consequences: undermining the advancement of equity and inclusion, constraining press freedom, and chilling free expression.

I went to management. I went to the police. I went to the FBI, CIA. The Committee to Protect Journalists took my case to the Department of Justice. Nothing changed. But I did. I changed as a person. I became angrier. More wary and withdrawn. I had police patrolling my neighborhood. I quit my job to protect my family and young children.

Dr. Michelle Ferrier, founder of TrollBusters and executive director of Media Innovation Collaboratory

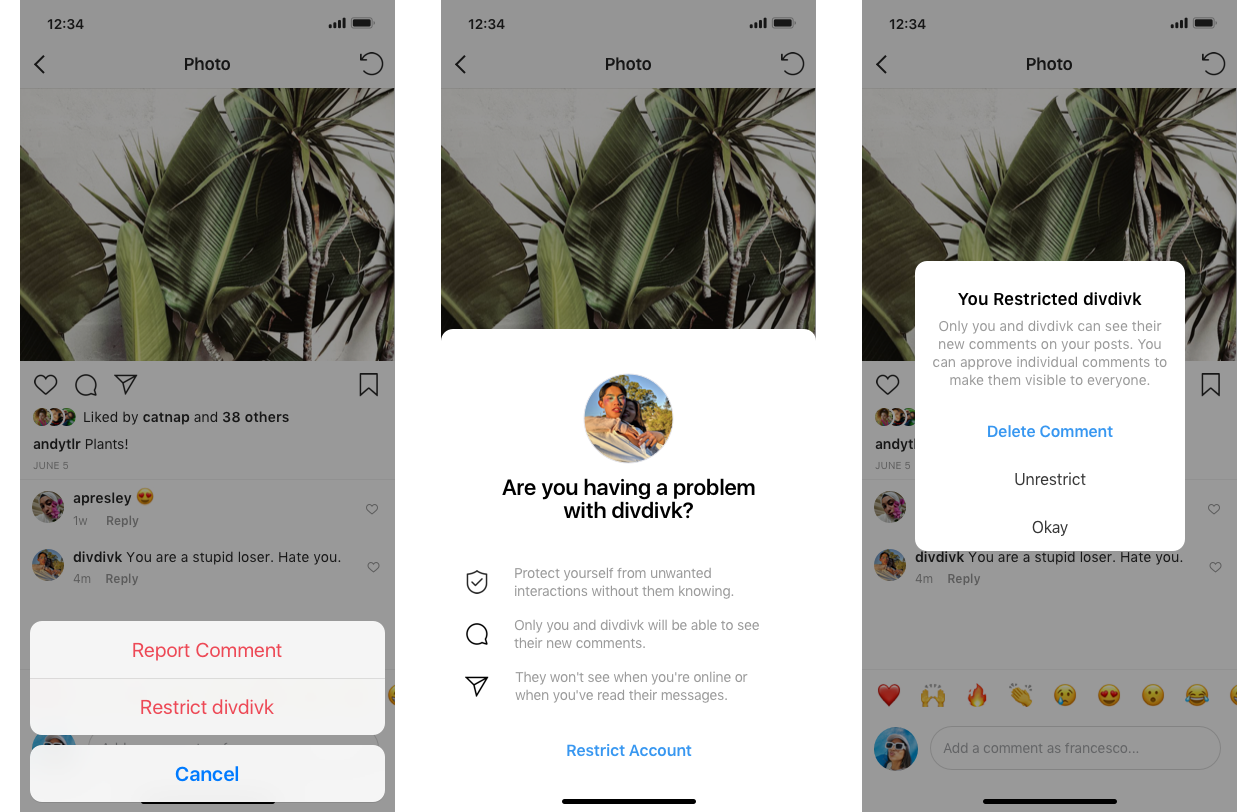

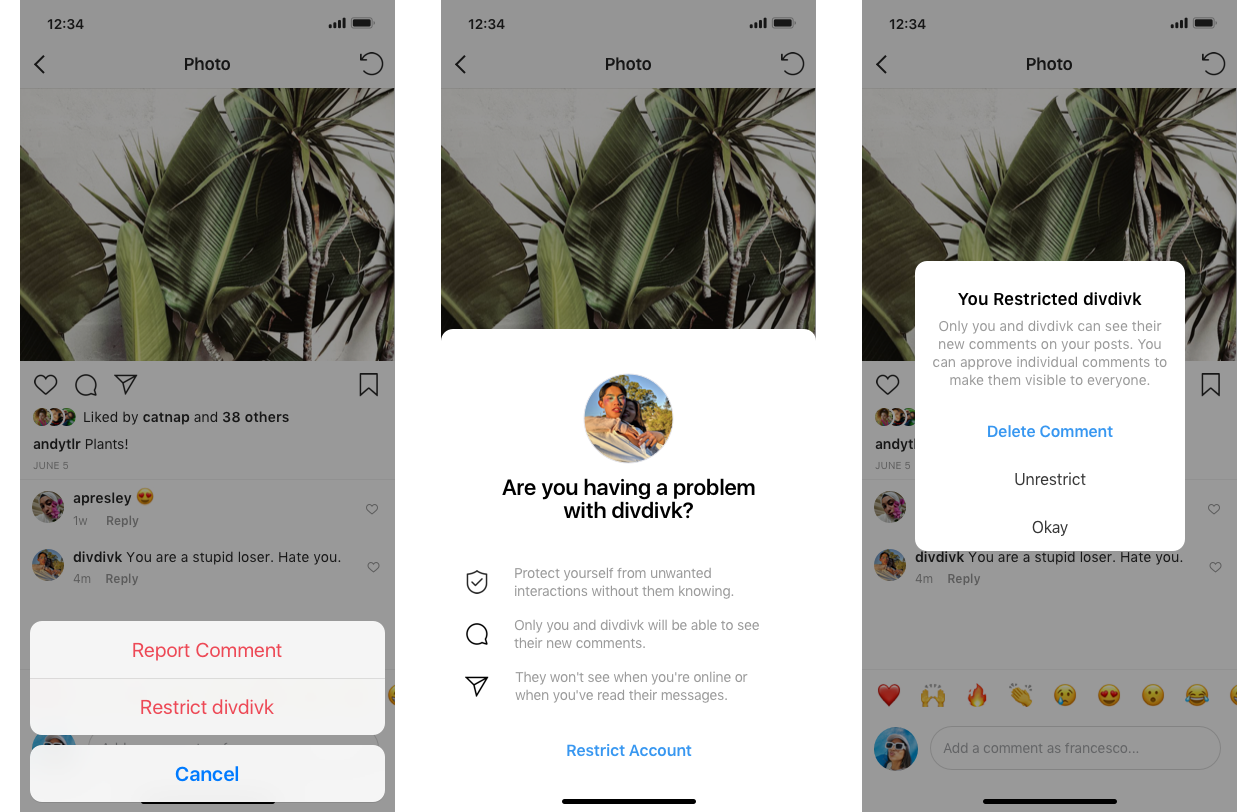

Shouting into the void: inadequate platform response

Hate and harassment did not begin with the rise of social media. But because sustaining user attention and maximizing engagement underpins the business model of these platforms, they are built to prioritize immediacy, emotional impact, and virality. As a result, they also amplify abusive behavior.20Amit Goldenberg and James J. Gross, “Digital Emotion Contagion,” Harvard Business School, 2020, hbs.edu/faculty/Publication%20Files/digital_emotion_contagion_8f38bccf-c655-4f3b-a66d-0ac8c09adb2d.pdf; Luke Munn, “Angry by design: toxic communication and technical architectures,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7, no. 53 (2020), doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00550-7; Molly Crockett, “How Social Media Amplifies Moral Outrage,” The Eudemonic Project, February 9 2020, eudemonicproject.org/ideas/how-social-media-amplifies-moral-outrage In prioritizing engagement over safety, many social media companies were slow to implement even basic features to address online harassment. When Twitter launched in 2006, users could report abuse only by tracking down and filling out a lengthy form for each individual abusive comment. The platform did not integrate a reporting button into the app until 2013;21Alexander Abad-Santos, “Twitter’s ‘Report Abuse’ Button Is a Good, But Small, First Step,” The Atlantic, July 31, 2013, theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/07/why-twitters-report-abuse-button-good-tiny-first-step/312689/; Abby Ohlheiser, “The Woman Who Got Jane Austen on British Money Wants To Change How Twitter Handles Abuse,” Yahoo! News, July 28, 2013, news.yahoo.com/woman-got-jane-austen-british-money-wants-change-024751320.html it offered a block feature (to limit communications with an abuser) early on, but did not provide a mute feature (to hide abusive comments without alerting and possibly antagonizing the abuser) until 2014.22Paul Rosania, “Another Way to Edit your Twitter Experience: With Mute,” Twitter Blog, May 12, 2014, blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/a/2014/another-way-to-edit-your-twitter-experience-with-mute.html While Facebook offered integrated reporting, blocking, and unfriending features within several years of its launch in 2004,23“Facebook Customer Service: Abuse,” Wayback Machine, December 2005, accessed March 2021, web.archive.org/web/20051231101754/http://facebook.com/help.php?tab=abuse it has since lagged behind in adding new features designed to address abuse. The platform only enabled users to ignore abusive accounts in direct messages in 2017 and to report abuse on someone else’s behalf in 2018.24Mallory Locklear, “Facebook introduces new tools to fight online harassment,” Engadget, December 19, 2017, engt.co/3qnl0Se; Antigone Davis, “New Tools to Prevent Harassment,” About Facebook, December 19, 2017, about.fb.com/news/2017/12/new-tools-to-prevent-harassment/; Antigone Davis, “Protecting People from Bullying and Harassment,” About Facebook, October 2, 2018, about.fb.com/news/2018/10/protecting-people-from-bullying/ When it launched in 2010, Instagram also required users to fill out a separate form to report abuse, and its rudimentary safety guidelines advised users to manually delete any harassing comments.25“User Disputes,” WayBack Machine, 2011, accessed February 16, 2021, web.archive.org/web/20111018040638/help.instagram.com/customer/portal/articles/119253-user-disputes Since 2016, the platform has gradually ramped up its efforts to address online harassment, pulling ahead of Facebook and Twitter, although Instagram did not actually introduce a mute button until 2018.26Megan McCluskey “Here’s How You Can Mute Someone on Instagram Without Unfollowing Them,” Time, May 22 2018, time.com/5287169/how-to-mute-on-instagram/

All of these features were added only after many women, people of color, religious and ethnic minorities, and LGBTQIA+ people, including journalists and politicians, had endured countless high-profile abuse campaigns and spent years advocating for change, applying pressure, and generating public outrage.27Alexandra Abad-Santos, “Twitter’s ‘Report Abuse’ Button Is a Good, But Small, First Step,” The Atlantic, July 31, 2013, theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/07/why-twitters-report-abuse-button-good-tiny-first-step/312689/; Amanda Marcotte, “Can These Feminists Fix Twitter’s Harassment Problem?,” Slate, November 7, 2014, slate.com/human-interest/2014/11/women-action-media-and-twitter-team-up-to-fight-sexist-harassment-online.html This timeline indicates a much broader issue in tech: in an industry that has boasted of its willingness to “move fast and break things,”28Chris Velazco, “Facebook can’t move fast to fix the things it broke,” Engadget, April 12, 2018, engadget.com/2018-04-12-facebook-has-no-quick-solutions.html efforts to protect vulnerable users are just not moving fast enough.

Users have noticed. According to a 2021 study from Pew Research Center, nearly 80 percent of Americans believe that social media companies are not doing enough to address online harassment.29Emily A. Vogel, “The State of Online Harassment,” Pew Research Center, January 13, 2021, pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/ Many of the experts and journalists PEN America consulted for this report concurred. Jaclyn Friedman, a writer and founder of Women, Action & the Media who has advocated with platforms to address abuse, says she often feels like she’s “shouting into a void because there’s no transparency or accountability.”30Jaclyn Friedman, interview with PEN America, May 28, 2020.

There is a growing international consensus that the private companies that maintain dominant social media platforms have a responsibility, in accordance with international human rights law and principles, to reduce the harmful impact of abuse on their platforms and ensure that they remain conducive to free expression.31Susan Benesch, “But Facebook’s Not a Country: How to Interpret Human Rights Law for Social Media Companies,” Yale Journal on Regulation Online Bulletin 3 (September 14, 2020), digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=jregonline According to the United Nations’ Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), corporations must “avoid infringing on the human rights of others and should address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved.”32“Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2011, ohchr.org/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf In March 2021, Facebook released a Corporate Human Rights Policy rooted in the UNGPs, which makes an explicit commitment to protecting the safety of human rights defenders, including “professional and citizen journalists” and “members of vulnerable groups advocating for their rights,” from online attacks.33 “Corporate Human Rights Policy,” Facebook, accessed March 2021, about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Facebooks-Corporate-Human-Rights-Policy.pdf The UNGPs further mandate that states must ensure that corporations live up to their obligations, which “requires taking appropriate steps to prevent, investigate, punish and redress such abuse through effective policies, legislation, regulations and adjudication.”34“Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2011, ohchr.org/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf

I am often harassed online when I cover white nationalism and anti-Semitism, especially in politics or when perpetrated by state actors. My face has even been photoshopped into an image of Jews dying in the gas chambers.

Laura E. Adkins, journalist and opinion editor of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency

What can platforms do now to reduce the burden of online abuse?

In this report, PEN America asks: What can social media companies do now to ensure that users disproportionately impacted by online abuse receive better protection and support? How can social media companies build safer spaces online? How can technology companies, from giants like Facebook and Twitter to small startups, design in-platform features and third-party tools that empower targets of abuse and their allies and disarm abusive users, while preserving free expression? What’s working, what can be improved, and where are the gaps? Our recommendations include both proactive measures that empower users to reduce risk and minimize exposure and reactive measures that facilitate response and alleviate harm; and accountability measures that deter abusive behavior.

Among our principal recommendations, we propose that social media companies should:

- Build shields that enable users to proactively filter abusive content (across feeds, threads, comments, replies, direct messages, etc.) and quarantine it in a dashboard, where they can review and address it with the help of trusted allies.

- Enable users to assemble rapid response teams and delegate account access, so that trusted allies can jump in to provide targeted assistance, from mobilizing supportive communities to helping document, block, mute, and report abuse.

- Create a documentation feature that allows users to quickly and easily record evidence of abuse—capturing screenshots, hyperlinks, and other publicly available data automatically or with one click—which is critical for communicating with employers, engaging with law enforcement, and pursuing legal action.

- Create safety modes that make it easier to customize privacy and security settings, visibility snapshots that show how adjusting settings impacts reach, and identities that enable users to draw boundaries between the personal and the professional with just a few clicks.

- For extreme or overwhelming abuse, create an SOS button that users could activate to instantly trigger additional in-platform protections and an emergency hotline (phone or chat) that provides personalized, trauma-informed support in real time.

- Create a transparent system of escalating penalties for abusive behavior—including warnings, strikes, nudges, temporary functionality limitations, and suspensions, as well as content takedowns and account bans—and spell out these penalties for users every step of the way.

Our proposals are rooted in the experiences of writers and journalists who identify as women, BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and/or members of religious or ethnic minorities in the United States, where PEN America’s expertise on online abuse is strongest. We recognize, however, that online abuse is a global problem and endeavor to note the risks and ramifications of applying strategies conceived in and for the United States internationally.35“Activists and tech companies met to talk about online violence against women: here are the takeaways,” Web Foundation, August 10, 2020, webfoundation.org/2020/08/activists-and-tech-companies-met-to-talk-about-online-violence-against-women-here-are-the-takeaways/ We focus on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram—because United States-based writers and journalists rely on these platforms most in their work,36Michelle P. Ferrier, “Attacks and Harassment: The Impact on Female Journalists and Their Reporting (Rep.),” IWMF/TrollBusters, 2018, iwmf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Attacks-and-Harassment.pdf; “Why journalists use social media,” NewsLab, 2018, newslab.org/journalists-use-social-media/#:~:text=The%20researchers%20found%20that%20eight,media%20in%20their%20daily%20work.&text=About%2073%20percent%20of%20the,there%20is%20any%20breaking%20news; “2017 Global Social Journalism Study,” Cision, accessed February 19, 2021, cision.com/content/dam/cision/Resources/white-papers/SJS_Interactive_Final2.pdf and because it is on these platforms that United States-based users report experiencing the most abuse.37“Online Hate and Harassment Report: The American Experience 2020,” ADL, June 2020, adl.org/online-hate-2020; see also Emily A. Vogels, “The State of Online Harassment,” Pew Research Center, January 13, 2021, pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/ But our recommendations are relevant to all technology companies that design products to facilitate communication and social interaction.

We draw a distinction between casual and committed abuse: the former is more organic and plays out primarily among individuals; the latter is premeditated, coordinated, and perpetrated by well-resourced groups. We make the case that technology companies need to better protect and support users facing both day-to-day abuse and rapidly escalating threats and harassment campaigns. While we propose tools and features that can both disarm abusers and empower targets and their allies, we recognize that the lines between abuser, target, and ally are not always clear-cut. In a heavily polarized environment, online abuse can be multidirectional. Though abusive trolls are often thought of as a “vocal and antisocial minority,” researchers at Stanford and Cornell Universities stress that “anyone can become a troll.”38Justin Cheng et al., “Anyone Can Become a Troll: Causes of Trolling Behavior in Online Discussions,” 2017, cs.stanford.edu/~jure/pubs/trolling-cscw17.pdf Research conducted in the gaming industry found that the vast majority of toxicity came not from committed repeat abusers but from regular users “just having a bad day.”39Jeffrey Lin, “Doing Something About The ‘Impossible Problem’ of Abuse in Online Games,” Vox, July 7, 2015, accessed February 16, 2021, vox.com/2015/7/7/11564110/doing-something-about-the-impossible-problem-of-abuse-in-online-gamesBecause a user can be either an abuser or a target at any time, tools and features designed to address online abuse must approach it as a behavior—not an identity.

No single strategy to fight online abuse will be perfect or future-proof. Any tool or feature for mitigating online abuse could have unintended consequences or be used in ways counter to its intended purpose. “You have to design all of these abuse reporting tools with the knowledge that they are going to be misused,” explains Leigh Honeywell, co-founder and CEO of Tall Poppy, a company that provides protection for individuals and institutions online.40Leigh Honeywell, interview with PEN America, May 15, 2020. Ensuring that systems are designed to empower users rather than simply prohibit bad behavior can help mitigate those risks, preserving freedom while also becoming more resilient to evolving threats.

If technology companies are serious about reducing the harm of online abuse, they must prioritize understanding the experiences and meeting the needs of their most targeted users. Every step of the way, platforms need to “center the voices of those who are directly impacted by the outcome of the design process,”41Sasha Costanza-Chock, Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need (MIT Press, 2020) argues Dr. Sasha Costanza-Chock, associate professor of civic media at MIT. Moreover, to build features and tools that address the needs of vulnerable communities, technology companies need staff, consultation, and testing efforts that reflect the perspectives and experiences of those communities. Staff with a diverse range of identities and backgrounds need to be represented across the organization—among designers, engineers, product managers, trust and safety teams, etc.—and they need to have the power to make decisions and set priorities. If platforms can build better tools and features to protect writers and journalists who identify as women, BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and members of religious or ethnic minorities, they can better serve all users who experience abuse.

You can’t have free expression of ideas if people have to worry that they’re going to get doxed or they’re going to get threatened. So if we could focus the conversation on how it is that we can create the conditions for free speech—free speech for reporters, free speech for women, free speech for people of color, free speech for people who are targeted offline—that is the conversation we have to have.

Mary Anne Franks, president of the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative and professor of law at the University of Miami

As an organization of writers committed to defending freedom of expression, PEN America views online abuse as a threat to the very principles we fight to uphold. When people stop speaking out and writing about certain topics due to fear of reprisal, everyone loses. Even more troubling, this threat is most acute when people are trying to engage with some of the most complex, controversial, and urgent questions facing our society—questions about politics, race, religion, gender and sexuality, and domestic and international public policy. Democratic structures depend on a robust, healthy discourse in which every member of society can engage. “You can’t have free expression of ideas if people have to worry that they’re going to get doxed or they’re going to get threatened,” notes Mary Anne Franks, president of the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative and professor of law at the University of Miami. “So if we could focus the conversation on how it is that we can create the conditions for free speech—free speech for reporters, free speech for women, free speech for people of color, free speech for people who are targeted offline—that is the conversation we have to have.”42Mary Anne Franks, interview with PEN America, May 22, 2020.

At the same time, we are leery of giving private companies unchecked power to police speech. Contentious, combative, and even offensive views often do not rise to the level of speech that should be banned, removed, or suppressed. Content moderation can be a blunt instrument. Efforts to combat online harassment that rely too heavily on taking down content, especially given the challenges of implicit bias in both human and automated moderation, risk sweeping up legitimate disagreement and critique and may further marginalize the very individuals and communities such measures are meant to protect. A post that calls for violence against a group or individual, for instance, should not be treated the same as a post that might use similar language to decry that very behavior.43Mallory Locklear, “Facebook is still terrible at managing hate speech,” Engadget, August 3, 2017, engadget.com/2017-08-03-facebook-terrible-managing-hate-speech.html; Tacey Jan, Elizabeth Dwoskin, “A White Man Called Her Kids the N-Word. Facebook Stopped Her from Sharing it.” The Washington Post, July 31st, 2017, wapo.st/2Z40H06 Furthermore, some tools that mitigate abuse can be exploited to silence the marginalized and censor dissenting views. More aggressive policing of content by platforms must be accompanied by stepped-up mechanisms that allow users to appeal and achieve timely resolution in instances where they believe that content has been unjustifiably suppressed or removed. Throughout this report, in laying out our recommendations, we address the tensions that can arise in countering abuse while protecting free expression, and propose strategies to mitigate weaponization and unintended consequences. While the challenges and tensions baked into reducing online harms are real, technology companies have the resources and power to find solutions. Writers, journalists, and other vulnerable users have, for too long, endured relentless abuse on the very social media platforms that they need to do their jobs. It’s time for technology companies to step up.

Empowering Targeted Users and Their Allies

In this section we lay out proactive and reactive measures that platforms can take to empower users targeted by online abuse and their allies. Proactive measures protect users from online abuse before it happens or lessen its impact by giving its targets greater control. Unfortunately proactive measures can sometimes be fraught from a free expression standpoint. Sweeping or sloppy implementation, often rooted in algorithmic and human biases abetted by a lack of transparency, can result in censorship, including of creative and journalistic content.44Scott Edwards, “YouTube removals threaten evidence and the people that provide it,” Amnesty International, November 1, 2017, amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/11/youtube-removals-threaten-evidence-and-the-people-that-provide-it/; Jillian C. York, “Companies Must Be Accountable to All Users: The Story of Egyptian Activist Wael Abbas,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, February 13 2018, eff.org/deeplinks/2018/02/insert-better-title-here; Abdul Rahman Al Jaloud et al., “Caught in the Net: The impact of “extremist” speech regulations on Human Rights content,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, Syrian Archive, and Witness, May 30, 2019, eff.org/files/2019/06/03/extremist_speech_regulations_and_human_rights_content_-_eff_syrian_archive_witness.pdf Reactive measures, such as blocking and muting to limit interaction with abusive content, mitigate the harms of online abuse once it is underway but do little to shield targets. Such features sidestep many of the first-order free expression risks associated with proactive measures but are often, on their own, insufficient to protect users from abuse.

It is important to bear in mind that both proactive and reactive measures are themselves susceptible to gaming and weaponization.45Katie Notopoulos, “How Trolls Locked My Twitter Account For 10 Days, And Welp,” BuzzFeed News, December 2, 2017, buzzfeednews.com/article/katienotopoulos/how-trolls-locked-my-twitter-account-for-10-days-and-welp; Tracey Jan, Elizabeth Dwoskin, “A White Man Called Her Kids the N-Word. Facebook Stopped Her from Sharing it.” The Washington Post, July 31st, 2017, wapo.st/2Z40H06; Russell Brandom, “Facebook’s Report Abuse button has become a tool of global oppression,” The Verge, September 2, 2014, theverge.com/2014/9/2/6083647/facebook-s-report-abuse-button-has-become-a-tool-of-global-oppression In many cases, the difference between an effective strategy and an ineffective or overly restrictive one depends not only on policies but also on the specifics of how tools and features are designed and whom they prioritize and serve. Our recommendations aim to strike a balance between protecting those who are disproportionately targeted by online abuse for their identity and profession and safeguarding free expression.

Proactive measures: Reducing risk and exposure

Proactive measures are often more effective than reactive ones because they can protect users from encountering abusive content—limiting their stress and trauma and empowering them to express themselves more freely. They can also enable users to reduce their risk and calibrate their potential exposure by, for example, fine-tuning their privacy and security settings and creating distinctions between their personal and professional identities online.

Today most major platforms provide some proactive protections, but these are often difficult to find, understand, and use. Many of the writers and journalists PEN America works with, including those interviewed for this report, were unaware of existing features and tools and found themselves scrambling to deal with online harassment only after it had been unleashed. “Young journalists,” says Christina Bellantoni, a professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, often “don’t familiarize themselves with policies and tools because they don’t predict they will ever face problems. When they do, it’s too late. Tools to help young journalists learn more about privacy settings from the outset would go a long way.”46Christina Bellantoni, email to PEN America, January 25, 2021. Social media companies should design and build stronger proactive measures, make them more accessible and user-friendly, and educate users about them.

I wasn’t prepared emotionally for the abuse I saw on my screen and, as a freelancer, received little support from publications. Now I sometimes avoid reporting on certain topics, or I publish pieces, but I just won’t post on social media because I am afraid of the blowback and would rather not deal with it. If I had additional tools to deal with abuse on social media, I would definitely use them. I could cover some topics and post them.

Jasmine Bager, journalist

Safety modes and visibility snapshots: Making it easier to control privacy and security

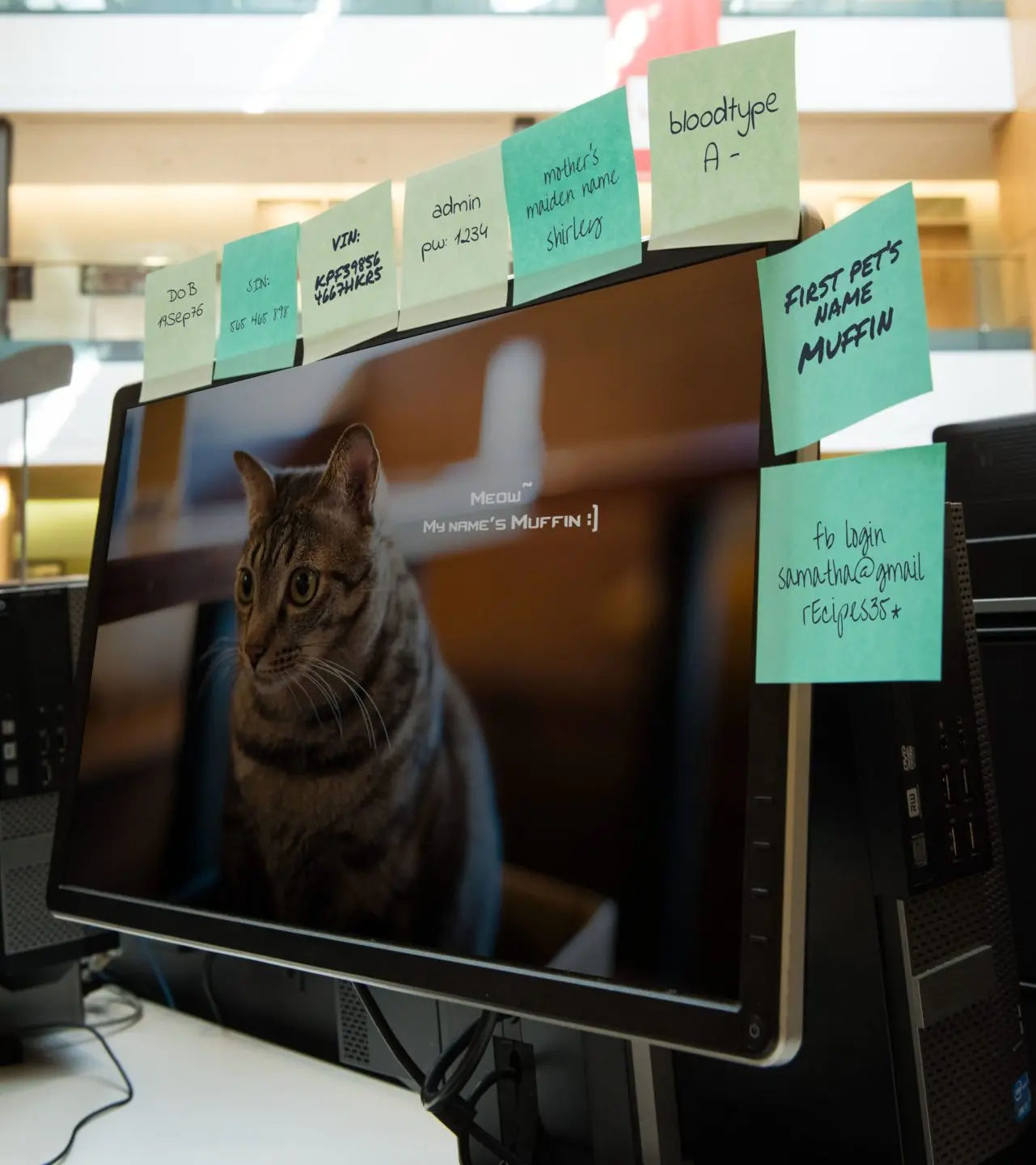

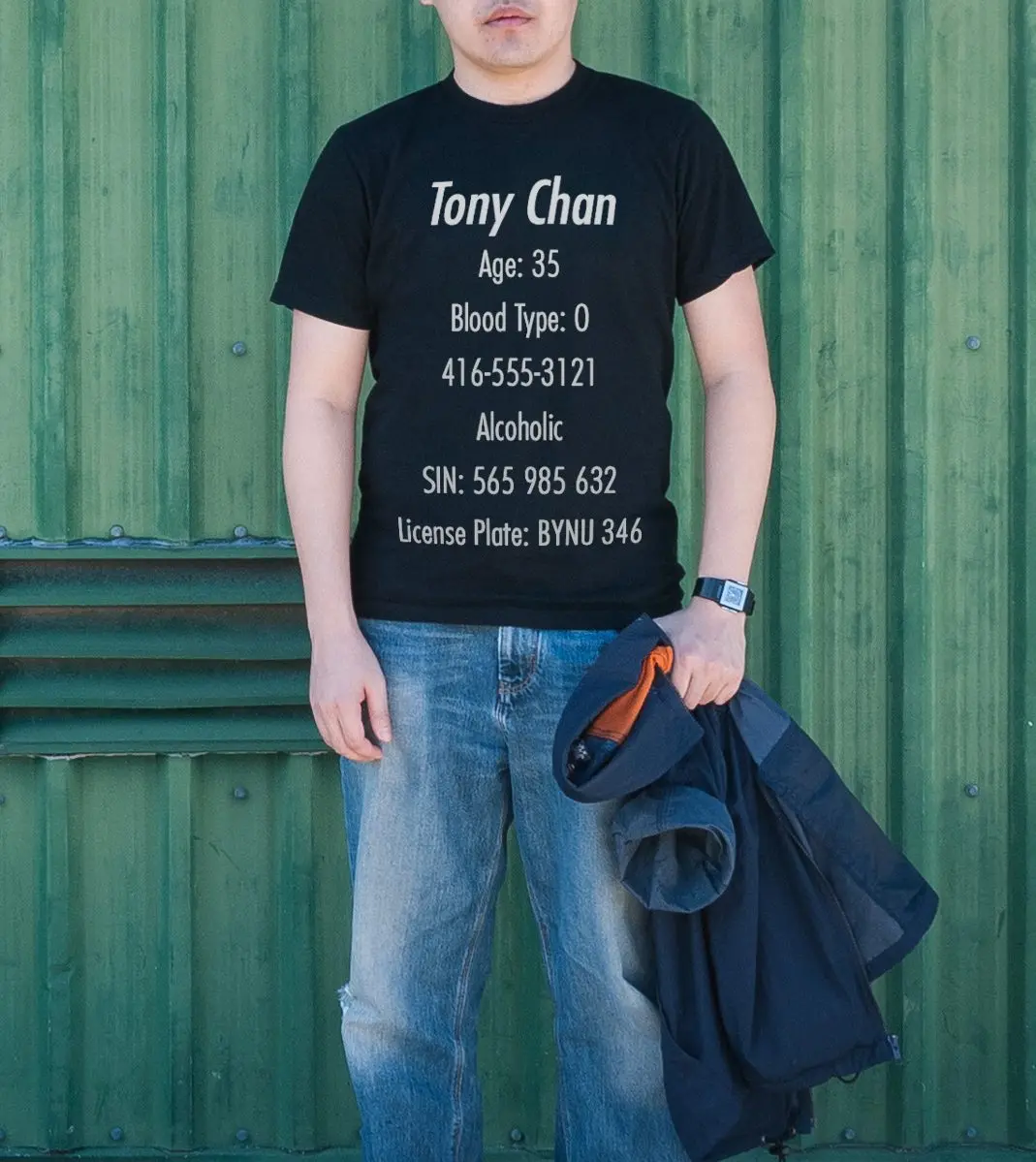

The challenge: Writers and journalists are especially vulnerable to hacking, impersonation, and other forms of abuse predicated on accessing or exposing private information.47Jeremy Wagstaff, “Journalists, media under attack from hackers: Google researchers,” Reuters, March 28, 2014, reuters.com/article/us-media-cybercrime/journalists-media-under-attack-from-hackers-google-researchers-idUSBREA2R0EU20140328; Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, “The dangers of journalism include getting doxxed. Here’s what you can do about it,” Poynter Institute, May 19, 2015, poynter.org/reporting-editing/2015/the-dangers-of-journalism-include-getting-doxxed-heres-what-you-can-do-about-it/ To reduce risks like these, users need to be able to easily fine-tune the privacy and security settings on their social media accounts, especially because platforms’ default settings often maximize the public visibility of content.48“Twitter is public by default, and the overwhelming majority of people have public Twitter accounts. Geolocation is off by default.” Email to PEN America from Twitter spokesperson, October 2020; Matthew Keys, “A brief history of Facebook’s ever-changing privacy settings,” Medium, March 21, 2018, medium.com/@matthewkeys/a-brief-history-of-facebooks-ever-changing-privacy-settings-8167dadd3bd0

Some platforms have gradually given users more granular control over their settings, which is a positive trend.49Matthew Keys, “A brief history of Facebook’s ever-changing privacy settings,” Medium, March 21, 2018, medium.com/@matthewkeys/a-brief-history-of-facebooks-ever-changing-privacy-settings-8167dadd3bd0 Providing users with maximum choice and control without overwhelming them is a difficult balancing act.50Kat Lo, interview with PEN America, May 19, 2020; Caroline Sinders, Vandinika Shukla, and Elyse Voegeli. “Trust Through Trickery,” Commonplace, PubPub, January 5, 2021, doi.org/10.21428/6ffd8432.af33f9c9 The usability of these tools is just as important as their sophistication. “Every year —like clockwork —Facebook has responded to criticisms of lackluster security and data exposure by rolling out ‘improvements’ to its privacy offerings,” writes journalist Matthew Keys. “More often than not, Facebook heralds the changes as enabling users to take better control of their data. In reality, the changes lead to confusion and frustration.”51Matthew Keys, “A Brief History of Facebook’s Ever-Changing Privacy Settings,” Medium, March 21, 2018, medium.com/@matthewkeys/a-brief-history-of-facebooks-ever-changing-privacy-settings-8167dadd3bd0

Adding to the problem, there is no consistency across platforms in how privacy and security settings work or the language used to describe them. These settings are often buried within apps or separate help centers and are time-consuming and challenging to find and adjust.52Caroline Sinders, Vandinika Shukla, and Elyse Voegeli. “Trust Through Trickery,” Commonplace, PubPub, January 5, 2021, doi.org/10.21428/6ffd8432.af33f9c9; Michelle Madejski, Maritza Johnson, Steven M Bellovin, “The Failure of Online Social Network Privacy Settings,” Columbia University Computer Science Technical Reports (July 8, 2011), doi.org/10.7916/D8NG4ZJ1 Even “Google’s own engineers,” according to Ars Technica, have been “confused” by its privacy settings.53Kate Cox, “Unredacted Suit Shows Google’s Own Engineers Confused by Privacy Settings,” ArsTechnica, August 25, 2020, arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2020/08/unredacted-suit-shows-googles-own-engineers-confused-by-privacy-settings/

While many writers and journalists want to maximize their visibility and user engagement, if they find themselves in the midst of an onslaught of abuse—or anticipate one—they need to quickly and easily reduce their visibility until the trouble has passed. Because tightening privacy has real trade-offs, understanding the implications of adjusting specific settings is critically important. As journalist Jareen Imam points out, when users find it “confusing to see what is public and what is not,” they struggle to weigh trade-offs and make informed choices.54Jareen Imam, interview with PEN America, August 25, 2020.

Existing features and tools: As some platforms add increasingly granular choices for adjusting settings, they are also experimenting with features to streamline the process. With Twitter’s “protect my tweets” and Instagram’s “private account” features, users can now tighten their privacy with a single click, restricting who can see their content or follow them. But they cannot then customize settings within these privacy modes to maintain at least some visibility and reach.55“About Public and Protected Tweets,” Twitter, accessed September 2020, help.twitter.com/en/safety-and-security/public-and-protected-tweets; “How do I set my Instagram account to private so that only approved followers can see what I share?,” Instagram Help Center, accessed February 19, 2021, facebook.com/help/instagram/426700567389543/?helpref=hc_fnav&bc[0]=Instagram%20Help&bc[1]=Privacy%20and%20Safety%20Center

Facebook’s settings are notoriously complicated, and users don’t have a one-click option to tighten privacy and security throughout an account.56In India, Facebook introduced a “Profile Picture Guard” feature in 2017 and seems to be experimenting with a new feature that allows users to “Lock my profile,” which means “people they are not friends with will no longer be able to see photos and posts — both historic and new — and zoom into, share and download profile pictures and cover photos.” However, this feature does not yet appear to be available in multiple countries. Manish Singh, “Facebook rolls out feature to help women in India easily lock their accounts,” TechCrunch, May 21, 2020, tcrn.ch/3uDiREJ Its users can proactively choose to limit the visibility of individual posts,57Justin Lafferty, “How to Control who sees your Facebook posts,” Adweek, March 22, 2013, adweek.com/digital/how-to-control-who-sees-your-facebook-posts/ but they cannot make certain types of content, such as a profile photo, private,58“How Do I Add or Change My Facebook Profile Picture?,” Facebook Help Center, accessed January 19, 2021, facebook.com/help/163248423739693?helpref=faq_content; “Who Can See My Facebook Profile Picture and Cover Photo?,” Facebook Help Center, accessed January 19, 2021, facebook.com/help/193629617349922?helpref=related&ref=related&source_cms_id=756130824560105 which can result in the misuse of profile photos for impersonation or non-consensual intimate imagery.59Woodrow Hartzog and Evan Selinger, “Facebook’s Failure to End ‘Public by Default’,” Medium, November 7, 2018, medium.com/s/story/facebooks-failure-to-end-public-by-default-272340ec0c07 The platform does offer user-friendly, interactive privacy and security checkups.60Germain, T., “How to Use Facebook Privacy Settings”, Consumer Reports, October 7, 2020, consumerreports.org/privacy/facebook-privacy-settings/; Matthew Keys, “A Brief History of Facebook’s Ever-Changing Privacy Settings,” Medium, March 21, 2018, medium.com/@matthewkeys/a-brief-history-of-facebooks-ever-changing-privacy-settings-8167dadd3bd0; “Safety Center,” Facebook, accessed December, 2020, facebook.com/safety

In trying to comprehend byzantine settings, some users have turned to external sources. Media outlets and nonprofits, including PEN America, offer writers and journalists training and guidance on tightening privacy and security on social media platforms.61PEN America and Freedom of the Press Foundation offer hands-on social media privacy and security training. See also: “Online Harassment Field Manual,” PEN America, accessed November 16th, 2020, onlineharassmentfieldmanual.pen.org/; Viktorya Vilk, “What to do if you’re the target of online harassment,” Slate, June 3, 2020, slate.com/technology/2020/06/what-to-do-online-harassment.html; Kozinski Kristen and Neena Kapur, “How to Dox Yourself on the Internet,” The New York Times, February 27, 2020, open.nytimes.com/how-to-dox-yourself-on-the-internet-d2892b4c5954 Third-party tools such as Jumbo and Tall Poppy walk users through adjusting settings step by step.62Casey Newton, “Jumbo is a powerful privacy assistant for iOS that cleans up your social profiles,” The Verge, April 9, 2019, theverge.com/2019/4/9/18300775/jumbo-privacy-app-twitter-facebook; “Product: Personal digital safety for everyone at work,” Tall Poppy, accessed September, 2020, tallpoppy.com/product/ While external tools and training are useful and badly needed, few writers, journalists, and publishers currently have the resources or awareness to take advantage of them.63Jennifer R. Henrichsen et al., “Building Digital Safety For Journalism: A survey of selected issues,” UNESCO, 2015, unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232358 (“Digital security training programs for human rights defenders and journalists are increasing. However, approximately 54 percent of 167 respondents to the survey for this report said they had not received digital security training.”) Moreover, the very existence of such tools and training is indicative of the difficulty of navigating privacy and security within the platforms themselves.

Recommendations: Platforms should provide users with robust, intuitive, user-friendly tools to control their privacy and security settings. Specifically, platforms should:

- Empower users to create and save “safety modes”—multiple, distinct configurations of privacy and security settings that they can then quickly activate with one click when needed.

- Twitter and Instagram should give users the option to fine-tune existing safety modes (“protect my tweets” and “private account,” respectively) after users activate them. These modes are currently limited in functionality because they are binary (i.e., the account is either private or not).

- Facebook should introduce a safety mode that allows users to go private with just one click, as Twitter and Instagram have already done, while also ensuring that users can then fine-tune specific settings in the new safety mode.

- Introduce “visibility snapshots” that clearly communicate to users, in real time, the implications of the changes they are making as they adjust their security and privacy settings. One solution is to provide users with a snapshot of what is publicly visible, as Facebook does with its “view as” feature.64“How can I see what my profile looks like to people on Facebook I’m not friends with?,” Facebook Help Center, accessed February 19, 2021, facebook.com/help/288066747875915 Another is to provide an estimate of how many or which types of users (followers, public, etc.) will be able to see a post depending on selected settings.

- Twitter and Instagram should add user-friendly, interactive privacy and security checkups, as Facebook has already done, and introduce visibility snapshots.

- Facebook should enable users to make profile photos private.

- Regularly prompt users, via nudges and reminders, to review their security and privacy settings and set up the safety modes detailed above. Prompts could proactively encourage users to reconsider including private information that could put them at risk (such as a date of birth or home address).

- Convene a multi-stakeholder coalition of technology companies, civil society organizations, and vulnerable users—or deploy a specific existing coalition such as the Global Network Initiative,65“Global Network Initiative,” Global Network Initiative, Freedom of Expression and Privacy, July 26, 2020, globalnetworkinitiative.org/ Online Abuse Coalition,66“Coalition on Online Abuse,” International Women’s Media Foundation, iwmf.org/coalition-on-online-abuse/ or Trust & Safety Professional Association67“Overview,” Trust and Safety Professional Association, 2021, tspa.info/—to coordinate consistent user experiences and terminology for account security and privacy across platforms.

My Instagram is probably the most personal account that I have. And actually, for a long time, it was a private account. But because of the pandemic, it’s impossible to do reporting without having this public. When you have a private account, you also close yourself off to sources that might want to reach out to tell you something really important … So it’s public now.

Jareen Imam, director of social newsgathering at NBC News

Identities: Distinguishing between the personal and the professional

The challenge: For many writers and journalists, having a presence on social media is a professional necessity.68“2017 Global Social Journalism Study,” Cision, accessed February 19, 2021, cision.com/content/dam/cision/Resources/white-papers/SJS_Interactive_Final2.pdf Yet the boundaries between the personal and professional use of social media accounts are often blurred. The importance of engaging with an audience and building a brand encourages the conflation of the professional with the personal.69Cara Brems et al., “Personal Branding on Twitter How Employed and Freelance Journalists Stage Themselves on Social Media,” Digital Journalism 5, no. 4 (May 3, 2016), tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21670811.2016.1176534?scroll=top&needAccess=true As journalist Allegra Hobbs wrote in The Guardian: “All the things that invite derision for influencers—self-promotion, fishing for likes, posting about the minutiae of your life for relatability points—are also integral to the career of a writer online.”70Allegra Hobbs, “The journalist as influencer: how we sell ourselves on social media,” The Guardian, October 21, 2019, theguardian.com/media/2019/oct/20/caroline-calloway-writers-journalists-social-media-influencers A 2017 analysis of how journalists use Twitter found that they “particularly struggle with” when to be “personal or professional, how to balance broadcasting their message with engagement and how to promote themselves strategically.”71Cara Brems et al., “Personal Branding on Twitter How Employed and Freelance Journalists Stage Themselves on Social Media,” Digital Journalism 5, no. 4 (May 3, 2016), tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21670811.2016.1176534 While writers and reporters may be mindful of the need for privacy, the challenge, as freelance journalist Eileen Truax explains, is that maintaining a social media presence paves the way for professional opportunities: “Many of the invitations I get to participate in projects come to me because they see my activity on Twitter.”72Eileen Truax, interview with PEN America, May 25, 2020.

This fusion of the personal and professional makes writers and journalists vulnerable. Private information found on social media platforms is weaponized to humiliate, discredit, and intimidate users, their friends, and their families. To mitigate risk, Jason Reich, vice president for corporate security at The New York Times, advises journalists to create distinct personal and professional accounts on social media wherever possible, fine-tune privacy and security settings accordingly, and adjust the information they include for each account.73Jason Reich, interview with PEN America, June 9, 2020. But following such procedures is challenging because platforms make it difficult to distinguish between personal and professional accounts, to migrate or share audiences between them, and to target specific audiences. While users can theoretically create and manage multiple accounts on most platforms, in practice a user who decides to create a professional account or page separate from an existing personal one has to start over to rebuild an audience.74Avery E Holton, Logan Molyneux, “Identity Lost? The personal impact of brand journalism,” SAGE 18, no. 2 (November 3, 2015): 195-210, doi.org/10.1177%2F1464884915608816

The COVID-19 pandemic—which has pushed more creative and media professionals into remote and fully digital work—has intensified this dilemma.75Bernard Marr, “How The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Fast-Tracking Digital Transformation In Companies,” Forbes, May 17, 2020, forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2020/03/17/how-the-covid-19-pandemic-is-fast-tracking-digital-transformation-in-companies/?sh=592af355a8ee; Max Willens, “‘But I’m still on deadline’: How remote work is affecting newsrooms,” Digiday, March 17, 2020, digiday.com/media/im-still-deadline-work-home-policies-affecting-newsrooms/ “My Instagram is probably the most personal account that I have,” says Jareen Imam, director of social newsgathering at NBC News. “And actually, for a long time, it was a private account. But because of the pandemic, it’s impossible to do reporting without having this public. When you have a private account, you also close yourself off to sources that might want to reach out to tell you something really important.… So it’s public now.”76Jareen Imam, interview with PEN America, August 25, 2020.

Existing features and tools: Twitter77“How to Manage Multiple Accounts,” Twitter, accessed September 28, 2020, help.twitter.com/en/managing-your-account/managing-multiple-twitter-accounts and Instagram78Gannon Burgett, “How to Manage Multiple Instagram Accounts,” Digital Trends, May 17, 2019, digitaltrends.com/social-media/how-to-manage-multiple-instagram-accounts/ allow individual users to create multiple accounts and toggle easily between them. Facebook, on the other hand, does not allow one user to create more than one account79“Can I Create Multiple Facebook Accounts?,” Facebook Help Center, accessed January 19, 2021, facebook.com/help/975828035803295/?ref=u2u; “Can I Create a Joint Facebook Account or Share a Facebook Account with Someone Else?,” Facebook Help Center, accessed January 19, 2021, facebook.com/help/149037205222530?helpref=related&ref=related&source_cms_id=975828035803295 and requires the use of an “authentic name”—that is, the real name that a user is known by offline.80“What names are allowed on Facebook?” Facebook Help Center, accessed February 8, 2021, facebook.com/help/112146705538576 While Facebook enables users to create “fan pages” and “public figure pages,”81“Can I Create Multiple Facebook Accounts?,” Facebook, accessed August 2020, facebook.com/help/975828035803295?helpref=uf_permalink these have real limitations: By prioritizing the posts of friends and family in users’ feeds, Facebook favors the personal over the professional, curbing the reach of public-facing pages and creating an incentive to invest in personal profiles.82“Generally, posts from personal profiles will reach more people because we prioritize friends and family content and because posts with robust discussion also get prioritized—posts from Pages or public figures very broadly get less reach than posts from profiles.” Email response from Facebook spokesperson, January 21, 2021; Adam Mosseri, “Facebook for Business,” Facebook, January 11, 2018, facebook.com/business/news/news-feed-fyi-bringing-people-closer-together; Mike Isaac, “Facebook Overhauls News Feed to focus on what Friends and Family Share,” The New York Times, January 11, 2018, nyti.ms/3sm6b3Z

All of the platforms analyzed in this paper are gradually giving users more control over their audience. Twitter is testing a feature that allow users to specify who can reply to their tweets83Suzanne Xie, “Testing, testing… new conversation settings,” Twitter, May 20, 2020, blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/product/2020/testing-new-conversation-settings.html#:~:text=Before%20you%20Tweet,%20you’ll,or%20only%20people%20you%20mention.&text=People%20who%20can’t%20reply,Comment,%20and%20like%20these%20Tweets. and recently launched a feature that allows users to hide specific replies.84Brittany Roston, “Twitter finally adds the option to publicly hide tweets,” SlashGear, November 21, 2019, slashgear.com/twitter-finally-adds-the-option-to-publicly-hide-tweets-21601045/#:~:text=To%20hide%20a%20tweet,%20tap,who%20shared%20the%20hidden%20tweet. Facebook gives users more control over the visibility of individual posts, allowing users to choose among “public,” “friends,” or “specific friends.”85“What audiences can I choose from when I share on Facebook?,” Facebook, accessed November 30, 2020, facebook.com/help/211513702214269 Instagram has a feature that lets users create customized groups of “close friends” and share stories in a more targeted way, though it has not yet expanded that feature to posts.86Arielle Pardes, “Instagram Now Lets You Share Pics with Just ‘Close Friends’,” Wired, November 30, 2018, wired.com/story/instagram-close-friends/ But none of these platforms allow individual users to share or migrate friends and followers among multiple accounts or between profiles and pages.87Email response from Facebook spokesperson, January 21, 2021; Email response from Instagram spokesperson, January 15, 2021; Email response from Twitter spokesperson, October 30, 2020.

Recommendations: Platforms should make it easier for users to create and maintain boundaries between their personal and professional identities online while retaining the audiences that they have cultivated. There are multiple ways to achieve this:

- Empower users to create and save “safety modes”—multiple, distinct configurations of privacy and security settings that they can then quickly activate with one click when needed.

- Give users greater control over who can see their individual posts (i.e., friends/followers versus subsets of friends/followers versus the wider public), which is predicated on the ability to group audiences and target individual posts to subsets of audiences. This is distinct from giving users the ability to go private across an entire account (see “Safety modes,” above).

- Like Twitter and Instagram, Facebook should make it possible for users to create multiple accounts and toggle easily between them, a fundamental, urgently needed shift from its current “one identity” approach. Facebook should also ensure that public figure and fan pages offer audience engagement and reach that are comparable to those of personal profiles.

- Like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram should make it easier for users to specify who can see their posts and allow users to migrate or share audiences between personal and professional online identities.

Mitigating risk: While most individual users are entitled to exert control over who can see and interact with their content, for public officials and entities on social media, transparency and accountability are paramount. The courts recently asserted, for example, that during Donald Trump’s presidency, it was unconstitutional for him to block users on Twitter because he was using his “presidential account” for official communications.88Knight First Amendment Inst. at Columbia Univ. v. Trump, No. 1:17-cv-5205 (S.D.N.Y. 2018) There are multiple related cases currently winding their way through the courts, including the ACLU’s lawsuit against state Senator Roy Scott of Colorado for blocking a constituent on Twitter.89“ACLU Sues Colorado State Senator for Blocking Constituent on Social Media,” ACLU of Colorado, June 11, 2019, aclu-co.org/aclu-sues-colorado-state-senator-for-blocking-constituent-on-social-media/ It is especially important that public officials and entities be required to uphold the boundaries between the personal and professional use of social media accounts and ensure that any accounts used to communicate professionally remain open to all constituents. Public officials and entities must also adhere to all relevant laws for record keeping in official, public communications, including on social media.

Account histories: Managing old content

The challenge: Many writers and journalists have been on social media for over a decade.90Ruth A. Harper, “The Social Media Revolution: Exploring the Impact on Journalism and News Media Organizations,” Inquiries Journal 2, no. 3, (2010), inquiriesjournal.com/articles/202/the-social-media-revolution-exploring-the-impact-on-journalism-and-news-media-organizations They joined in the early days, when platforms like Facebook were used primarily in personal life and privacy settings often defaulted to “public” and were not granular or easily accessible.91Matthew Keys, “A brief history of Facebook’s ever-changing privacy settings,” Medium, March 21, 2018, medium.com/@matthewkeys/a-brief-history-of-facebooks-ever-changing-privacy-settings-8167dadd3bd0 But the ways that creative and media professionals use these platforms has since broadened in scale, scope, and reach. Writers’ and journalists’ long histories of online activity can be mined for old posts that, when resurfaced and taken out of context, can be deployed to try to shame a target or get them reprimanded or fired.92Kenneth P. Vogel, Jeremy W. Peters, “Trump Allies Target Journalists Over Coverage Deemed Hostile to White House,” The New York Times, August 25, 2019, nytimes.com/2019/08/25/us/politics/trump-allies-news-media.html; Aja Romano, “The ‘controversy’ over journalist Sarah Jeong joining the New York Times, explained,” Vox, August 3, 2018, vox.com/2018/8/3/17644704/sarah-jeong-new-york-times-tweets-backlash-racism

Existing features and tools: On Twitter and Instagram, users can delete content piecemeal and cannot easily search through or sort old content, which is cumbersome and impractical.93Abby Ohlheiser, “There’s no good reason to keep old tweets online. Here’s how to delete them,” The Washington Post, July 30, 2018, wapo.st/3o01WHJ; David Nield, “How to Clean Up Your Old Social Media Posts,” Wired, June 14, 2020, wired.com/story/delete-old-twitter-facebook-instagram-posts/ In June 2020, Facebook launched “manage activity,” a feature that allows users to filter and review old posts by date or in relation to a particular person and to archive or delete posts individually or in bulk.94“Introducing Manage Activity,” Facebook, June 2, 2020, about.fb.com/news/2020/06/introducing-manage-activity/ Manage activity is an important and useful new feature, but it does not allow users to search by keywords and remains difficult to find. There are multiple third-party tools that allow users to search through and delete old tweets and posts en masse;95In interviews, PEN America journalists and safety experts mentioned Tweetdelete and Tweetdeleter. Additional third-party tools include Semiphemeral, Twitwipe, and Tweeteraser for Twitter and InstaClean for Instagram. however, some of them cost money and most require granting third-party access to sensitive accounts, which poses its own safety risks depending on the cybersecurity and privacy practices (and ethics) of the developers.

Recommendations: Platforms should provide users with integrated and robust features to manage their personal account histories, including the ability to search through old posts, review them, make them private, delete them, and archive them—individually and in bulk. Specifically:

- Twitter and Instagram should integrate a feature that allows users to search, review, make private, delete, and archive old content—individually and in bulk.

- Facebook should expand its new manage activity feature to enable users to search by keywords and should make this feature more visible and easier to access.

Mitigating risk: PEN America believes that users should have control over their own social media account histories. Users already have the ability to delete old content on most platforms and via multiple third-party tools. But giving users the ability to purge account histories, especially in bulk, does have drawbacks. Abusers can delete old posts that would otherwise serve as evidence in cases of harassment, stalking, or other online harms. And by removing old content, public officials and entities using social media accounts in their official capacities may undermine accountability and transparency. There are ways to mitigate these drawbacks. It is vital that people facing online abuse are able to capture evidence of harmful content, which is needed for engaging law enforcement, pursuing legal action, and escalating cases with the platforms. For that reason, this report advocates for a documentation feature that would make it easier for targets to quickly and easily preserve evidence of abuse (see “Documentation,” below). In the case of public officials or entities deleting account histories, tools that archive the internet, such as the Wayback Machine, are critically important resources for investigative journalism.96“Politwoops: Explore the Tweets They Didn’t Want You to See,” Propublica, projects.propublica.org/politwoops/; Valentina De Marval, Bruno Scelza, “Did Bolivia’s Interim President Delete Anti-Indigenous Tweets?,” AFP Fact Check, November 21, 2019, factcheck.afp.com/did-bolivias-interim-president-delete-anti-indigenous-tweets There are also federal laws—most centrally the Freedom of Information Act—and state-level laws that require public officials to retain records that may be disclosed to the public; these records include their statements made on social media.975 U.S.C § 552; “Digital Media Policy,” Department of the Interior, accessed February 19, 2021, doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/elips/documents/470_dm_2_digital_media_policy_1.pdf Public officials and entities using social media accounts in their official capacities must adhere to applicable record retention laws, which should apply to social media as they do to other forms of communication.

Other people in my friend circle have to take into account that, being Black and queer, I get more negativity than they would. If they’re white or cisgender or heteronormative, they’ll come back and say, ‘You know what? Jordan is getting a lot of flack, so let’s step up to the plate.’

Jordan, blogger (requested to be identified only by their first name)

Rapid response teams and delegated access: Facilitating allyship

The challenge: Online abuse isolates its targets. A 2018 global study from TrollBusters and the IWMF found that 35 percent of women and nonbinary journalists who had experienced threats or harassment reported “feeling distant or cut off from other people.”98Michelle Ferrier, “Attacks and Harassment: The Impact on Female Journalists and Their Reporting,” TrollBusters and International Women’s Media Foundation, September 13, 2018, iwmf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Attacks-and-Harassment.pdf Many people targeted by online abuse suffer in silence because of the stigma, shame, and victim blaming surrounding all forms of harassment.99Angie Kennedy, Kristen Prock, “I Still Feel Like I Am Not Normal,” Trauma Violence & Abuse 19, no. 5, (December 2, 2018), researchgate.net/publication/309617025_”I_Still_Feel_Like_I_Am_Not_Normal”_A_Review_of_the_Role_of_Stigma_and_Stigmatization_Among_Female_Survivors_of_Child_Sexual_Abuse_Sexual_Assault_and_Intimate_Partner_Violence Often targets have no choice but to engage with hateful or harassing content—in order to monitor, mute, report, and document it—which can be overwhelming, exhausting, and traumatizing.100Erin Carson, “This is your brain on hate,” CNET, July 8, 2017, cnet.com/news/heres-how-online-hate-affects-your-brain/

Many of the writers and journalists in PEN America’s network emphasize the importance of receiving support from others in recovering from episodes of online abuse. Jordan, a blogger who requested to be identified only by their first name, explained: “Other people in my friend circle have to take into account that, being Black and queer, I get more negativity than they would. If they’re white or cisgender or heteronormative, they’ll come back and say, ‘You know what? Jordan is getting a lot of flack, so let’s step up to the plate.’”101“Story of Survival: Jordan,” PEN America Online Harassment Field Manual, October 31, 2017, onlineharassmentfieldmanual.pen.org/stories/jordan-blogger-tennessee/

Existing features and tools: Users can help one another report abuse on Twitter,102“Report abusive behavior,” Twitter, accessed October 2020, twitter.com/en/safety-and-security/report-abusive-behavior Facebook,103“How to Report Things,” Facebook, accessed October 2020, facebook.com/help/1380418588640631/?helpref=hc_fnav and Instagram.104“Abuse and Spam,” Instagram, accessed October 2020, instagram.com/215140222006271#:~:text=If%20you%20have%20an%20Instagram,Guidelines%20from%20within%20the%20app But for allies to offer more extensive support—such as blocking or checking direct messages (DMs) on a target’s behalf—they need to have access to the target’s account. In-platform features that securely facilitate allyship are rare, and those that exist were not specifically designed for this purpose. As a result, many targets of online abuse either struggle on their own or resort to ad hoc strategies, such as handing over passwords to allies,105Jillian C. York, “For Bloggers at Risk: Creating a Contingency Plan,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, December 21, 2011, eff.org/deeplinks/2011/12/creating-contingency-plan-risk-bloggers which undermines their cybersecurity at precisely the moment when they are most vulnerable to attacks.

On Facebook, the owner of a public page can grant other users “admin” privileges, but this feature is not available for personal Facebook profiles.106“How do I manage roles for my Facebook page?,” Facebook, accessed October 2020, facebook.com/help/187316341316631 Similarly, Instagram allows users to share access and designate “roles,” but only on business accounts.107“Manage Roles on a Shared Instagram Account,” Instagram, accessed December 2020, help.instagram.com/218638451837962?helpref=related Twitter comes closest to supporting delegated access with its “teams” feature in TweetDeck, letting users share access to a single account without using the same password and be granted owner, admin, or contributor status.108“How to use the Teams feature on Tweetdeck,” Twitter, accessed October 2020, help.twitter.com/en/using-twitter/tweetdeck-teams

While useful, these features were designed to facilitate professional productivity and collaboration and meant primarily for institutional accounts or pages.109Sarah Perez, “Twitter enables account sharing in its mobile app, powered by Tweetdeck Teams,” TechCrunch, September 8, 2017, techcrunch.com/2017/09/08/twitter-enables-account-sharing-in-its-mobile-app-powered-by-tweetdeck-teams/ (“This change will make it easier for those who run social media accounts for businesses and brands to post updates, check replies, send direct messages and more, without having to run a separate app.”) The reality is that, like many users, writers and journalists use social media accounts for both personal and professional purposes and need integrated support mechanisms designed specifically to deal with online abuse. Facebook offers a feature that enables users to proactively select a limited number of trusted friends to help them if they get locked out of their account.110“How can I contact the friends I’ve chosen as trusted contacts to get back into my Facebook account?,” Facebook, accessed October 2020, facebook.com/help/213343062033160 If the company adapted this feature to allow users to proactively select several trusted friends to serve as a rapid response team during episodes of abuse—and added this feature to its new “registration for journalists”111“Register as a Journalist with Facebook,” Facebook Business Help Center, accessed January 20, 2021, facebook.com/business/help/620369758565492?id=1843027572514562—it could serve as an example for other platforms.

In PEN America’s trainings and resources, we advise writers and journalists to proactively designate a rapid response team—a small network of trusted allies—who can be called upon to rally broader support and provide specific assistance, such as account monitoring or temporary housing in the event of doxing or threats.112“Deploying Supportive Cyber Communities,” PEN America Online Harassment Field Manual, accessed February 2021, onlineharassmentfieldmanual.pen.org/deploying-supportive-cyber-communities/ Several third-party tools and networks are trying to fill the glaring gap in peer support. As Lu Ortiz, founder and executive director of the anti-harassment nonprofit Vita Activa, explains: “Peer support groups are revolutionary because they destigmatize the process of asking for help, provide solidarity, and generate resilience and strategic decision making.”113Lu Ortiz, email to PEN America, January 21, 2021 The anti-harassment nonprofit TrollBusters coordinates informal, organic support networks for journalists.114Michelle Ferrier, interview with PEN America, February 12, 2021. The anti-harassment nonprofit Hollaback! has developed a platform called HeartMob that provides the targets of abuse with support and resources from a community of volunteers.115“About HeartMob,” HeartMob, accessed December 2020, iheartmob.org/about “Our goal,” says co-founder Emily May, “is to reduce trauma for people being harassed online by giving them the immediate support they need.”116Emily May, email to PEN America, January 25, 2021. Block Party, a tool currently in beta for Twitter, gives users the ability to assign “helpers” to assist with monitoring, muting, or blocking abuse.117“Frequently asked questions,” Block Party, accessed October 2020, blockpartyapp.com/faq/#what-does-a-helper-do (“When you add a Helper, you can set their permissions to be able to view only, flag accounts, or even mute and block on your behalf. Mute and block actions apply directly to your Twitter account, but Helpers can’t post tweets from your Twitter account nor can they access or send direct messages.”) Squadbox lets users designate a “squad” of supporters to directly receive and manage abusive content in email in-boxes.118Katilin Mahar, Amy X. Zhang, David Karger, “Squadbox: A Tool to Combat Email Harassment Using Friendsourced Moderation,” CHI 2018: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, no. 586 (April 21, 2018): 1-13, doi/10.1145/3173574.3174160; Haystack Group, accessed October 2020, haystack.csail.mit.edu/ These tools and communities provide models for how platforms could integrate peer support.

In PEN America’s trainings and resources, we advise writers and journalists to proactively designate a rapid response team—a small network of trusted allies—who can be called upon to rally broader support and provide specific assistance, such as account monitoring or temporary housing in the event of doxing or threats.119“Deploying Supportive Cyber Communities,” PEN America Online Harassment Field Manual, accessed February 2021, onlineharassmentfieldmanual.pen.org/deploying-supportive-cyber-communities/ Several third-party tools and networks are trying to fill the glaring gap in peer support. As Lu Ortiz, founder and executive director of the anti-harassment nonprofit Vita Activa, explains: “Peer support groups are revolutionary because they destigmatize the process of asking for help, provide solidarity, and generate resilience and strategic decision making.”120Lu Ortiz, email to PEN America, January 21, 2021 The anti-harassment nonprofit TrollBusters coordinates informal, organic support networks for journalists.121Michelle Ferrier, interview with PEN America, February 12, 2021. The anti-harassment nonprofit Hollaback! has developed a platform called HeartMob that provides the targets of abuse with support and resources from a community of volunteers.122“About HeartMob,” HeartMob, accessed December 2020, iheartmob.org/about “Our goal,” says co-founder Emily May, “is to reduce trauma for people being harassed online by giving them the immediate support they need.”123Emily May, email to PEN America, January 25, 2021. Block Party, a tool currently in beta for Twitter, gives users the ability to assign “helpers” to assist with monitoring, muting, or blocking abuse.124“Frequently asked questions,” Block Party, accessed October 2020, blockpartyapp.com/faq/#what-does-a-helper-do (“When you add a Helper, you can set their permissions to be able to view only, flag accounts, or even mute and block on your behalf. Mute and block actions apply directly to your Twitter account, but Helpers can’t post tweets from your Twitter account nor can they access or send direct messages.”) Squadbox lets users designate a “squad” of supporters to directly receive and manage abusive content in email in-boxes.125Katilin Mahar, Amy X. Zhang, David Karger, “Squadbox: A Tool to Combat Email Harassment Using Friendsourced Moderation,” CHI 2018: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, no. 586 (April 21, 2018): 1-13, doi/10.1145/3173574.3174160; Haystack Group, accessed October 2020, haystack.csail.mit.edu/ These tools and communities provide models for how platforms could integrate peer support.

Recommendations: Platforms should add new features and integrate third-party tools that facilitate peer support and allyship. Specifically, platforms should:

- Enable users to proactively designate a limited number of trusted allies to serve as a rapid response team—a small network of trusted allies who can be called upon to work together or individually to monitor, report, and document abuse that is publicly visible and rally a broader online community to help.