Booklash

Literary Freedom, Online Outrage, and the Language of Harm

Key Findings:

Finding 1

Finding 2

Finding 3

Introduction: The “Problematic” Discourse and Books

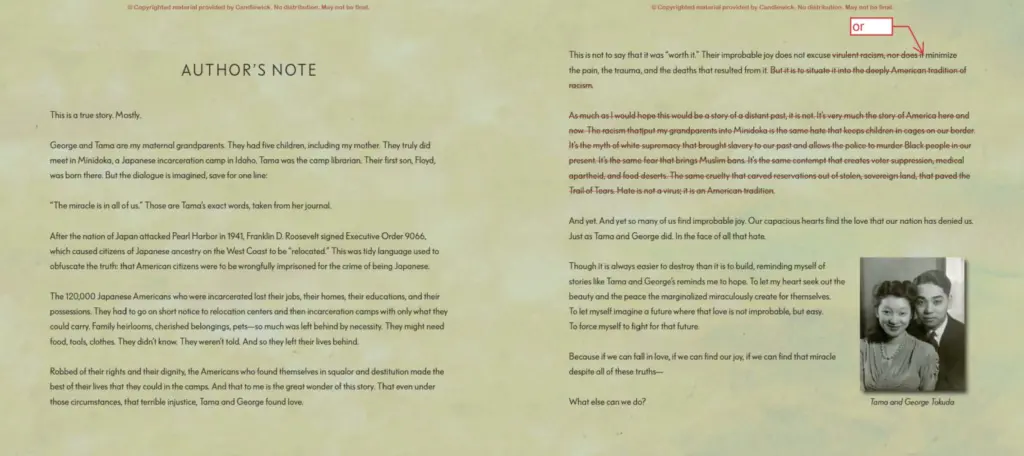

In the past few years, the literary community has seen waves of activism that have galvanized much-needed and overdue change in the industry. National movements like Black Lives Matter and #MeToo have pushed publishers to recommit to accountability, representation, and social justice more broadly. Readers are challenging stereotypes, stimulating new conversations about responsible storytelling, and pushing for a more diverse, representative publishing industry.

As PEN America previously detailed in Reading Between the Lines: Race, Equity, and Book Publishing, our 2022 report on roadblocks to greater diversity in the industry, this new wave of literary activism is pushing for a more diverse literary canon, one that better reflects the American populace today.1James Tager and Clarisse Rose Shariyf, “Reading Between the Lines: Race, Equity, and the Publishing Industry,” PEN America, October 17, 2022, https://pen.org/report/race-equity-and-book-publishing/ That work is far from done, and PEN America has called upon publishers to reexamine some of their core conventions – from the structure of author advances to the norms of the acquisition process –to open up greater opportunities for writers with varying backgrounds and degrees of access to the industry.2James Tager and Clarisse Rose Shariyf, “Reading Between the Lines: Race, Equity, and the Publishing Industry,” PEN America, October 17, 2022, pen.org/report/race-equity-and-book-publishing/

Yet amid these necessary shifts, some readers, writers, and critics are pushing to draw new lines around what types of books, tropes, and narrative conventions should be seen as permissible and who has the legitimacy, authority, or “right” to write certain stories. At one extreme, some critics are calling for an identity-essentialist approach to literature, holding that writers can only responsibly tell the stories that relate to their own identity and experiences.3Shuli de la Fuente-Lau, “What Does Own Voices Mean? And Why It Matters,” Little Feminist, February 22, 2021, littlefeminist.com/2021/02/22/what-does-own This approach is incompatible with the freedom to imagine that is essential to the creation of literature, and it denies readers the opportunity to experience stories through the eyes of writers offering varied and distinctive lenses.

These critics have argued that “problematic” books or authors deserve special censure from the literary world—with “problematic” being a catchall term ranging from an author accused of committing a crime to one who relies on lazy narrative conventions. Fiction that is regarded as employing stereotypes, outdated tropes, or unrealistic character sketches may be described as threatening “harm” or being “dangerous.” In the past several years, books deemed problematic due to their authorship, their content, or both have been subjected to boycotts, calls for withdrawals, and harassment of their authors. Some have argued that merely to read the book is to become complicit in its alleged harms. While proponents of these arguments are, of course, free to make them, such arguments risk laying the groundwork for, and justifying, the ostracism of authors and ideas and the narrowing of literary freedom writ large.

Many of these conversations are happening in the realm of young adult (YA) literature. Engaged readers and writers predominantly represent younger generations especially attuned to the moral imperative of inclusivity and the ills of stereotypes and other potentially offensive tropes in literature. Even so, critics who apply a rhetoric of harm in their evaluation of YA books risk playing into the hands of book banners, who also use the language of harm and describe books as “dangerous.” It is imperative that the literary field chart a course that advances diversity and equity without making these values a cudgel against specific books or writers deemed to fall short in these areas.

In articulating this imperative, PEN America draws in part from the Manifesto on the Democracy of the Imagination, a statement unanimously endorsed by over 100 PEN Centers at the 2019 PEN International Congress, which says in part: “PEN stands against notions of national and cultural purity that seek to stop people from listening, reading and learning from each other. . . . PEN believes the imagination allows writers and readers to transcend their own place in the world to include the ideas of others.”4“The Democracy of the Imagination Manifesto,” PEN International, October 2, 2019, pen.org.ua/en/manifest-demokratiya-tvorchoy

Authors and publishers have felt compelled to respond to this intensifying form of literary criticism, which is amplified through online discourse. Authors accused of racial or other forms of insensitivity have sometimes apologized, sometimes held course. In rare cases, authors have taken the extraordinary step of delaying and editing their book to respond to criticism, even choosing to withdraw it from publication entirely. In some cases feedback is taken and changes made truly voluntarily, though it is sometimes unclear whether authors do so because they genuinely accept the critique levied against them or because they feel forced to compromise their artistic vision to appease their most vocal critics or to avoid inviting more widespread opprobrium.

Publishers, too, can feel obligated to address these criticisms, through apologetic statements, changes to author tours, or requests for edits. There have been several instances when publishers have responded by doing something far more drastic: canceling a book contract or pulling a book from circulation.

In researching this report, PEN America examined 16 cases of author, publisher, or estate withdrawals of books between 2021 and 2023, with the most recent occurring in June 2023.5Three Rivers by Sarah Stusek (2023); The Snow Forest by Elizabeth Gilbert (2023); Reframe Your Brain: The User Interface with Happiness and Success by Scott Adams (2023); Bad & Boujee by Jennifer M. Buck (2022); The Blue Eye by Roderick Hunt (2022); The Dictator by Jonah Winter and illustrated by Barry Blitt (2022); Deep Denial by Chris Cuomo (2021); Ook and Gluk: Kung Fu Cavemen from the Future by Dav Pilkey (2021); Philip Roth by Blake Bailey (2021); The Splendid Things We Planned: A Family Portrait by Blake Bailey (2021); The Fight for Truth by John Mattingly (2021); The Tyranny of Big Tech by Josh Hawley (2021); Jesus For You by author Ravi Zacharias and various other titles (2021); Welcome to the Woke Trials: How Identity Killed Progressive Politics by Julie Burchill; Various Dr. Seuss titles (2021); one title withdrawn during this date range that is not named in the report for confidentiality reasons. None of these books were withdrawn based on any allegation of containing factual disinformation, nor the glorification of violence, or plagiarized passages. Their content or author was simply deemed offensive. Fewer than half of the books are available for readers to buy today, and only four are still in print.6Oxford Languages definition of “in print”: (of a book) available from the publisher.

While decisions to remove books from circulation remain relatively rare, each withdrawal sets a precedent: one where publishers see jettisoning a book as a legitimate response to criticism, even criticism from those who have not read the book. The normalization of this tactic threatens to shrink the space for risk-taking and creative freedom in the publishing world.

Some of the objections to books – as harmful, dangerous, or hateful, especially to children – that have led to author and publisher withdrawals mirror rhetoric that has led to pulling books from school and library shelves in Florida, Texas, and elsewhere. If advocates for an open society accept the principle that books should be as widely available as possible, that readers should have access to a broad range of topics and perspectives, that offense taken by certain groups of readers cannot be grounds to withhold books from availability, and that withdrawing books from circulation is rarely—if ever—justified, these precepts must extend not just to government book banning but also to how the literary community governs itself.

In major publishing houses, staffers have increasingly expressed opposition to specific book contracts with writers whom they allege to be promoting forms of harm, in some cases going so far as to demand that contracts be nullified. The debate within the literary field has become a debate within publishing houses, calling into question how these publishers define and balance their mission and moral obligations.

Perhaps the most profound articulation of American publishers’ mission and obligations comes from the Freedom to Read Statement, a document first drafted by a group of librarians and publishers in 1953 in response to McCarthyism and the moral panics of the Red Scare. It reads, in part:

We believe that free communication is essential to the preservation of a free society and a creative culture. We believe that these pressures toward conformity present the danger of limiting the range and variety of inquiry and expression on which our democracy and our culture depend. We believe that every American community must jealously guard the freedom to publish and to circulate, in order to preserve its own freedom to read. We believe that publishers and librarians have a profound responsibility to give validity to that freedom to read by making it possible for the readers to choose freely from a variety of offerings.

The imperative to “jealously guard” the freedom to read is a principle that stretches beyond adherence to the First Amendment and beyond vigilance against government interference. This guardianship also requires a stalwart defense of the right of authors to write books that others may find offensive—and the right of publishers to publish them, and of readers to choose to read them.

Of course, readers and the general public have the right to express their strong views, including on social media. Robust, even contentious public debate about books and literature is part of a vibrant democracy. And authors and publishers should be open to criticism for the books they release, including charges of racial, gender, or other forms of insensitivity. When challenged with such criticism, they should be afforded the space to reflect, engage in dialogue, and—where warranted—to change their minds. Advocates for free expression need not deny that, under particular circumstances, language may lead to concrete, measurable harm. This is particularly so when individuals or groups are subjected to pervasive stereotyping and denigration over long periods of time. Indeed, the written word’s power to prompt change in the real world is what makes writers the target of autocrats and oppressors around the world. But we are concerned when the rhetoric of harm is levied against a book such that any defense of the book’s literary or social merits is seen as automatically invalid. Such tactics mirror those of book banners who cite particular scenes or passages depicting disturbing events or that are sexually explicit to argue for removal of whole works of literature from classrooms or libraries.

Books are controversial for myriad reasons. As former PEN America President Salman Rushdie has famously said: “Literature is a loose cannon. This is a very good thing.” Defending a robust space for creative expression and for a broad exchange of ideas and perspectives requires making room for controversial books, books that offend, books that “get it wrong.” Employing a separate standard for books that are alleged to promote harm threatens the robustness of that space.

PEN America hopes this report will shed light on these debates, offer guidance, and argue for a firm defense of literary freedom. As a society, we need to be able to engage in free debate about books without resorting to denying readers the opportunity to read these books and come to their own conclusions.

The Freedom to Read Statement

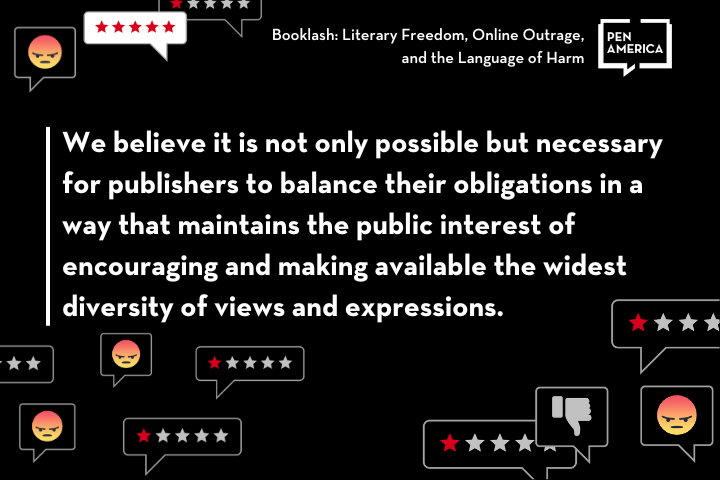

As private businesses, publishers have a legal right to independently determine what and whom they will publish, including when to cancel or withdraw a book or contract. And while American publishers do not have a legal responsibility to uphold freedom of expression, as government officials do under the First Amendment, they have long committed to a social and moral vision of themselves as guarantors of both the author’s freedom to create and the reader’s freedom to read. These commitments have been most forcefully enumerated in the American Association of Publishers/American Library Association Freedom to Read Statement.

The Statement was drafted in 1953, at the height of the second Red Scare, by a delegation of over 3,000 librarians and publishers in direct response to the pressures of McCarthyism, which aimed to set new, politically driven moral standards for what ideas and perspectives were acceptable in American society. The finalized statement established commitments for publishers and librarians regarding the freedom to read.

The Statement made headlines around the country—national and regional newspapers like The Washington Post and The Baltimore Sun ran it in full, and it garnered endorsements from a broad range of other publications, including TIME, Newsweek, and The New Republic.

The Statement was updated in 1973 and 2004. Members of the American Association of Publishers, including nearly 140 publishers, have committed themselves to it.

The Statement’s core propositions are:

- It is in the public interest for publishers and librarians to make available the widest diversity of views and expressions, including those that are unorthodox, unpopular, or considered dangerous by the majority.

- Publishers, librarians, and booksellers do not need to endorse every idea or presentation they make available. It would conflict with the public interest for them to establish their own political, moral, or aesthetic views as a standard for determining what should be published or circulated.

- It is contrary to the public interest for publishers or librarians to bar access to writings on the basis of the personal history or political affiliations of the author.

- There is no place in our society for efforts to coerce the taste of others, to confine adults to the reading matter deemed suitable for adolescents, or to inhibit the efforts of writers to achieve artistic expression.

- It is not in the public interest to force a reader to accept the prejudgment of a label characterizing any expression or its author as subversive or dangerous.

- It is the responsibility of publishers and librarians, as guardians of the people’s freedom to read, to contest encroachments upon that freedom by individuals or groups seeking to impose their own standards or tastes upon the community at large; and by the government whenever it seeks to reduce or deny public access to public information.

- It is the responsibility of publishers and librarians to give full meaning to the freedom to read by providing books that enrich the quality and diversity of thought and expression. By the exercise of this affirmative responsibility, they can demonstrate that the answer to a “bad” book is a good one, the answer to a “bad” idea is a good one.

PEN America believes that these principles remain as relevant today as they were in 1953 and that they should serve as a guiding touchstone for all publishers. To that end, in 2023, PEN America—and every living past PEN America president—joined with all of the “Big Five” publishers (Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House, and Simon & Schuster) and hundreds of others publishers, authors, and free expression and literary organizations to re-sign the statement on the 70th anniversary of its signing.7In addition to current PEN America president Ayad Akhtar, this list includes Kwame Anthony Appiah, Louis Begley, Ron Chernow, Joel Conarroe, Jennifer Egan, Frances FitzGerald, Peter Godwin, Francine Prose, Salman Rushdie, Michael Scammell, and Andrew Solomon; https://uniteagainstbookbans.org/freedomtoread/#signatories.

Methods and Report Layout

Research for this report involved substantial desk research from publicly available sources as well as conversations with more than two dozen industry professionals, including editors, publishing executives, literary agents, authors, and attorneys. Of these interviewees, 14 of the authors, editors, and literary agents we spoke with had personally experienced or participated in a situation where a book was withdrawn from intended or actual publication. Many interviewees spoke on condition of anonymity, either to protect their professional connections or to avoid taking a public stance on a hotly debated issue.

Part I of the report examines major debates in the literary arena on themes of identity and harm. We examine several controversies of the past few years over books that were alleged to contain harmful stereotypes, racially appropriative language, or otherwise “problematic” content when viewed through the lens of equity. This section also explores the issue of toxicity in online literary spaces and the extent to which social media outrage has impacted the book review process. We then critically examine several arguments that are gaining currency in the literary world regarding authors who write from diverse perspectives or who explore narratives from cultures not their own—that is, the question of who can write what stories.

The subsequent sections examine the ways that writers and publishers have responded to the critique that their intended or published book is dangerous or harmful—primarily allegations that the book or author is insensitive or inappropriate toward people of color or other marginalized communities.

Part II focuses on actions that authors have taken in response, while Part III focuses on actions that publishing institutions have taken. Part IV focuses on the phenomenon of publishing staff emerging as a voice of increasingly open dissent against controversial authors, to the extent of calling for publishers to cancel contracts. The report ends with conclusions and recommendations, including a call for literary and publishing institutions to uplift the Freedom to Read Statement as a set of principles that all conscientious literary citizens should support.

Part I: The New Debates Over Representation, Harm, And Identity In Literature

A New Forum for Debate

In the past decade, many debates over a book’s merits have migrated from the pages of established critical forums, like book reviews and newspapers, to social media feeds. On online platforms like Goodreads, “BookTok,” and “Book Twitter,”8After this report was sent to layout, Elon Musk announced the rebranding of Twitter to X. readers can make their opinions—and criticisms—heard by fellow readers, authors, and industry power players like never before.

One anonymous editor who stewarded a book through significant social media scrutiny told PEN America that online platforms have transformed the feedback loop between publishers and readers. “Before, there was a wall—you would have no way to get in touch with a publisher,” she explained. “But social media has changed people’s ability to get their message in front of the people in charge.”9PEN America interview with a former editor at a Big Five publishing house, March 2023. This democratizing effect can be a powerful force for change. Campaigns like #MeToo and #WeNeedDiverseBooks10This campaign grew into the nonprofit organization We Need Diverse Books, founded in 2014: diversebooks.org have empowered individuals to speak directly to and demand change from previously unreachable institutions.

Another such movement has been the #OwnVoices campaign. In 2015, YA author Corinne Duyvis first used this hashtag on Twitter to recommend books “about diverse characters written by authors from that same diverse group.”11“Corinne Duyvis, “#OwnVocies,” Corinne Duyvis, accessed July 31, 2023, corinneduyvis.net/ownvoices/ Duyvis’s tweet went viral in authors’ circles and—in a testament to Book Twitter’s growing power—spawned a drive in the industry to cultivate, support, and celebrate writers from historically underrepresented backgrounds. The hashtag itself became a mainstay of marketing campaigns, deal announcements, trade reviews, and literary discourse—conversations that drove the creation of initiatives like #DVPit, an annual event connecting emerging “diverse voices” with agents.12Claire Kirch, “Q&A with Corinne Duyvis,” Publishers Weekly, September 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/childrens/childrens-authors/article/84336-q-a-with-corinne-duyvis.html; Shannon Steffens, “Despite Controversy, #OwnVoices is Here to Make a Difference,” WWU Undergraduate and Graduate Scholarship, Spring 2021, cedar.wwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1496&context=wwu_honors

The rise of social media as a primary setting for literary discourse brings many benefits. These accessible forums give voice to communities that are traditionally underrepresented in critics’ circles and introduce opinions and judgments that may fall outside the general consensus. “Now readers can directly influence the publishing industry,” Beth Driscoll, an expert on contemporary book culture and global publishing, wrote about Goodreads in 2021. “And compared to established tastemakers and gatekeepers, these readers are more likely to be young, to be women, to be people of colour; not necessarily already well-networked or located in metropolitan centres of London and New York.”13Beth Driscoll, “How Goodreads is Changing Book Culture,” Kill Your Darlings, June 15, 2021, killyourdarlings.com.au/article/how-goodreads-is-changing-book-culture/# They also provide the opportunity for authors to engage in direct dialogue with their fans and critics.

Toxicity in Online Literary Spaces

At the same time, certain now-commonplace patterns of activity in online literary forums raise serious concerns. Commentators have noted that online literary conversations have become increasingly toxic – with authors being subjected to an intense volume of negative social media comments, condemnations, and public call-outs, for writing on specific topics or from certain perspectives, frequently from commentators who have not read the book in question.

In this report, PEN America describes certain patterns of activity as “toxic” in reference to their potentially corrosive effect on the freedoms to imagine, read, and publish as outlined in the Freedom to Read Statement. PEN America stands firm in its support of open debate and discourse, especially when it comes to literary interpretation. However, certain forms of “toxic” literary activity shade into explicit harassment and threats. There is also an element of volume and virality, where what is at issue is not the content of individual critiques but their pile-on nature. Many of these tactics, like online review-bombing and coordinated calls for book withdrawal, threaten to narrow – rather than expand – the space for the very dialogue we seek to protect.

These forms of toxicity have been particularly prevalent in the YA space, surging to the fore around 2016 and often involving allegations of racism directed at a particular author or book.14See e.g. Lucy V. Hay and Lixzie Fry, “‘Toxic YA’ Twitter Controversy is Actually 2 Difficult Debates,” accessed July 31, 2023, lucyvhayauthor.com/toxic-ya-twitter-controversy-is-actually-2-difficult-debates/; Jesse Singal, “Teen Fiction Twitter is Eating Its Young,” Reason, June 2019, reason.com/2019/05/05/teen-fiction-twitter-is-eating-its-young/; Molly Templeton, “YA Twitter Can Be Toxic, But It Also Points Out Real Problems,” Buzzfeed News, June 24, 2019, buzzfeednews.com/article/mollytempleton/ya-twitter-books-publishing-amelie-wen-zhao-social-media; “While the motivation behind the movement for more diverse voices is commendable,” one essayist wrote, “the manifestation of this impulse on social media has been nothing short of cannibalistic.”15Jesse Singal, “Teen Fiction Twitter is Eating Its Young,” Reason, June 2019, reason.com/2019/05/05/teen-fiction-twitter-is-eating-its-young/

There are growing expectations that YA authors maintain an online presence and interact with readers and critics. “As YA experienced drastic change as a category and Twilight pushed it to soaring new heights, Twitter became fundamental to the rapidly expanding community forming around it,” bookseller Nicole Brinkley explained in an essay on the subject. “YA publishing did two things very differently: first, the YA publishing industry made its target audience—its readers, its bloggers, its BookTubers and Bookstagrammers—part of its professional network. . . . Second, the YA publishing industry decided that Twitter was an essential platform for YA writers. Put simply, YA authors needed to be active on Twitter.”16Nicole Brinkley, “Did Twitter break YA? (Misshelved #6),” Coursehero, July 2, 2021, https://tinyletter.com/misshelved/letters/did-twitter-break-ya-misshelved-6

Social media imposes hefty demands on authors. Brinkley’s essay noted that today’s “YA publishing professionals must enact performances of perfection online: They must be constantly accessible (as demanded by the needs of their own marketing), while responding to everything that is happening all of the time (as demanded by their audience).”17Nicole Brinkley, “Did Twitter break YA? (Misshelved #6),” Coursehero, July 2, 2021, https://tinyletter.com/misshelved/letters/did-twitter-break-ya-misshelved-6

This expectation of “performances of perfection”, paired with social media algorithms that reward outrage over nuance, can produce a combustible mix. Over the past decade a series of pitched controversies have erupted in the YA field, with readers engaging in online campaigns to categorically label a book “problematic.” A selection of examples:

- The Raven King (2017), by Maggie Stiefvater, was accused of racism for several passages in which characters make fun of a half-Korean character18Scha Zakir, “It’s Raining Racist Authors: Time to get an Umbrella,” Affinity Magazine, February 21, 2017, affinitymagazine.us/2017/02/21/its-raining-racist-authors-time-to-get-an-umbrella/

- Everything, Everything (2017), by Nicola Yoon, was accused of ableism, in part, for the reveal that the protagonist was not in fact disabled19Jennifer J. Johnson, “Review: Everything, Everything by Nicola Yoon,” Disability in KidLit, September 4, 2015, disabilityinkidlit.com/2015/09/04/review-everything-everything-by-nicola-yoon/; Alaina Leary, “What “Everything, Everything” Gets Wrong About Living as a Disabled Person,” Teen Vogue, May 22, 2017, teenvogue.com/story/everything-everything-disabled-representation

- Sad Perfect (2017), by Stephanie Elliot, was accused of being triggering to those who had struggled with eating disorders20Aila, “ARC Review: Sad Perfect by Stephanie Elliot,” One Way or an Author, March 6, 2017, onewayoranauthor.wordpress.com/2017/03/06/arc-review-sad-perfect-by-stephanie-elliot

- When We Was Fierce (2016), by E.E. Charlton-Trujillo, was accused of racism for its use of an imagined Black “street dialect”21Alison Flood, “Publisher Delays YA Novel Amid row Over Invented Black ‘Street Dialect,’” The Guardian, August 16, 2016, theguardian.com/books/2016/aug/16/delays-ya-row-over-invented-black-vernacular-when-we-was-fierce

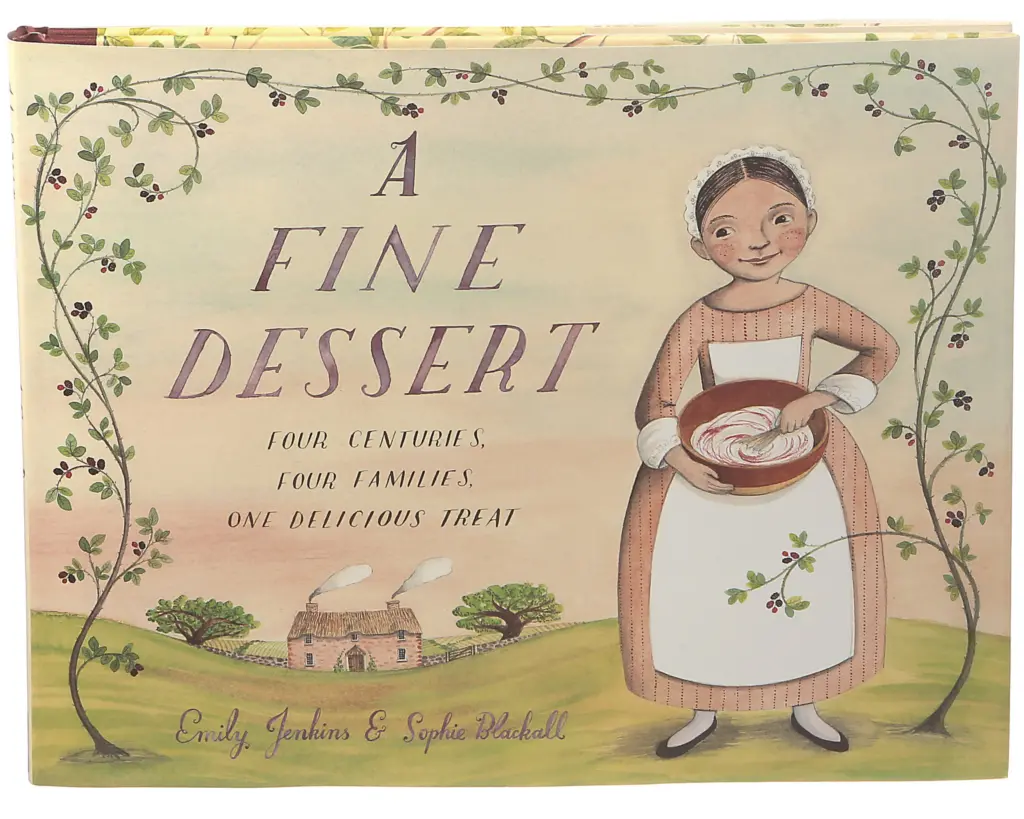

- A Fine Dessert (2015), by Emily Jenkins and with illustrations by Sophie Blackall, was accused of racism for its images of “smiling slaves”22Jennifer Schuessler, “‘A Fine Dessert’: Judging a Book by the Smile of a Slave,” The New York Times, November 6, 2015, nytimes.com/2015/11/07/books/a-fine-dessert-judging-a-book-by-the-smile-of-a-slave.html

- The Court of Thorn and Roses series (2015-present), by Sarah J. Maas, was accused of lacking diversity and misrepresenting people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals23Anna Garrison, “Let’s Unpack the Controversy Around ‘ACOTAR’ Author Sarah J. Maas,” Distractify, March 20, 2023, distractify.com/p/sarah-j-maas-controversy

- The Traitor’s Kiss (2017), by Erin Beaty, was accused of appropriating the story of Mulan and perpetuating “dark aggressor” stereotypes24Erin Beaty, “The Traitor’s Kiss,” Goodreads, accessed July 31, 2023, goodreads.com/en/book/show/29346870

- American Heart (2018), by Laura Moriarty, was accused of perpetuating a “white savior” narrative25See e.g. Emily May, “‘But I wasn’t done asking questions. I was . . .’” Goodreads, accessed July 31, 2022, goodreads.com/review/show/2117029381

- The Continent, by Keira Drake (2018), was accused of its “troubling portrayals within of people of color and native backgrounds.”26Lila Shapiro, “Can You Revise a Book to Make it More Woke?,” Vulture, February 18, 2018, goodreads.com/review/show/2117029381

“Problematic” is a term with no agreed-upon definition, but in practice such a charge has increasingly been employed as a sort of moral litmus test, a totalizing judgment on a book’s legitimacy, the legitimacy of those who choose to read it, and the viability of certain topics and perspectives.

Public outcry can erupt before a book even reaches shelves, meaning that people are reacting to promotional materials, small excerpted sections circulated online, or the impressions of a single reader. The controversy surrounding All the Crooked Saints, Maggie Steifvater’s 2017 YA fantasy novel, offers a glaring example: When news broke of its magical realist take on a fictional Latin-American community in Colorado, reviewers tanked the book’s Goodreads score before Stiefvater had even completed the manuscript.27Kat Rosenfield, “The Toxic Drama of YA Twitter,” Vulture, August 7, 2017, vulture.com/2017/08/the-toxic-drama-of-ya-twitter.html One Goodreads review—posted more than six months before the book’s release—reads, “Oh look, another racist, appropriating book by a clueless white author. Trash.”28Edith, “Oh look, another racist…” Goodreads, March 21, 2017, goodreads.com/book/show/30025336-all-the-crooked-saints

Allegations that a book is problematic—be they charges of racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, cultural appropriation, use of stereotypical tropes or conventions, or other issues—can drive public – and publisher – response to a book. One example of this is The Black Witch, a 2017 fantasy novel by Laurie Forest. The novel centers on a young protagonist attending university in a fictional magical society steeped in racism. The protagonist’s character arc addresses the racism she grew up with; Forest has described her novel as dealing with issues of race.

But while the book would go on to become a New York Times bestseller, it also became embroiled in controversy within the YA world. It began when bookstore employee Shauna Sinyard wrote a 9,000-word review blasting The Black Witch as “the most dangerous, offensive book I have ever read. . . . It was ultimately written for white people. It was written for the type of white person who considers themselves to be not-racist and thinks that they deserve recognition and praise for treating POC like they are actually human.” Sinyard, who is herself white, added that the book’s premise was “racist, ableist, homophobic, and . . . written with no marginalized people in mind.” As evidence, she quoted such dialogue as “The Kelts are not a pure race like us. They’re more accepting of intermarriage, and because of this, they’re hopelessly mixed.”29Kat Rosenfield, “The Toxic Drama of YA Twitter,” Vulture, August 7, 2017, vulture.com/2017/08/the-toxic-drama-of-ya-twitter.html What her review failed to contextualize, however, was that these quotes from the book’s racist characters provide the starting point for the protagonist’s narrative arc.

The review kicked off a wave of backlash against the book: The publisher, Harlequin Teen, reportedly received a torrent of emails demanding cancellation. The book’s Goodreads page was “review-bombed” with negative ratings, even as many negative reviewers acknowledged that they had not read it, casting their negative ratings as a form of protest against the book’s perceived racism.30Kat Rosenfield, “The Toxic Drama of YA Twitter,” Vulture, August 7, 2017, vulture.com/2017/08/the-toxic-drama-of-ya-twitter.html; Sadie Williams, “Vermont Fantasy Novel ‘The Black Witch’ Sparks Internet Fury,” Seven Days, April 26, 2017, sevendaysvt.com/vermont/vermont-fantasy-novel-the-black-witch-sparks-internet-fury/Content?oid=5298299

When book reviewer Kirkus gave the book a starred review, dozens of commentators demanded a retraction. The uproar was so pronounced that Kirkus felt compelled to run a follow-up essay. Editor Vicky Smith defended both the review and the importance of giving authors space to write objectionable characters, writing: “How are we as a society to come to grips with our own repugnance if we do not confront it? Literature has a long history as a place to confront our ugliness, and its role in provoking both thought and change in thought is a critical one. We feel that The Black Witch fits squarely in this tradition.”31Vicky Smith, “On Disagreement,” Kirkus, April 11, 2017, kirkusreviews.com/news-and-features/articles/disagreement/

Some social media commentators, taking up the call to protest the book, cast their objections in the language of harm.One tweeted: “Hey @HarlequinTEEN, I’d like to know what’s your intend [sic] regarding THE BLACK WITCH? Will changes be made to avoid ppl—TEENS—being hurt?”32Kat Rosenfield, “The Toxic Drama of YA Twitter,” Vulture, August 7, 2017, vulture.com/2017/08/the-toxic-drama-of-ya-twitter.html A teen blogger posted that she found the sentences that she saw, the ones that had been cherry-picked by critics to bolster their points, to be “very hurtful . . . just harmful and triggering.”33Kat Rosenfield, “The Toxic Drama of YA Twitter,” Vulture, August 7, 2017, vulture.com/2017/08/the-toxic-drama-of-ya-twitter.html She went on to urge others not to read The Black Witch, saying it caused her “emotional pain,” although she acknowledged she had not actually read it beyond those cherry-picked passages.

Some critics also called upon others not to read the book, with some describing reading it as a racist act.34Kat Rosenfield, “The Toxic Drama of YA Twitter,” Vulture, August 7, 2017, vulture.com/2017/08/the-toxic-drama-of-ya-twitter.html One tweet argued: “Reading a book specifically because it’s been called out for racism doesn’t make you a champion of independent thought. It makes you racist.”35Kat Rosenfield, “The Toxic Drama of YA Twitter,” Vulture, August 7, 2017, vulture.com/2017/08/the-toxic-drama-of-ya-twitter.html

The controversy did not derail the book, which gained commercial success, and the author herself has said that it was “a good conversation for me to learn from, to make sure I’m not lazy in my use of language.”36Sadie Williams, “Vermont Fantasy Novel ‘The Black Witch’ Sparks Internet Fury,” Seven Days, April 26, 2017, sevendaysvt.com/vermont/vermont-fantasy-novel-the-black-witch-sparks-internet-fury/Content?oid=5298299 But some of the responses—review-bombing the Goodreads page, calls for the publisher to withdraw publication, demands for reviewers to recant their endorsements, arguments that it was unethical to read a book accused of “hurting” teens—could raise the stakes and potential consequences of writing on certain topics and from certain perspectives, creating a chilling effect on future works.

This concern may be particularly pronounced for younger or debut writers. Author Kazuo Ishiguro has argued that “a climate of fear” is leading less established writers to avoid writing outside their personal experience. “I very much fear for the younger generation of writers,” he told the BBC, who “rightly perhaps feel that their careers are more fragile, their reputations are more fragile and they don’t want to take risks.”37Rebecca Jones, “Sir Kazuo Ishiguro warns of young authors self-censoring out of ‘fear’,” BBC, March 1, 2021, bbc.in/3QvzD20.

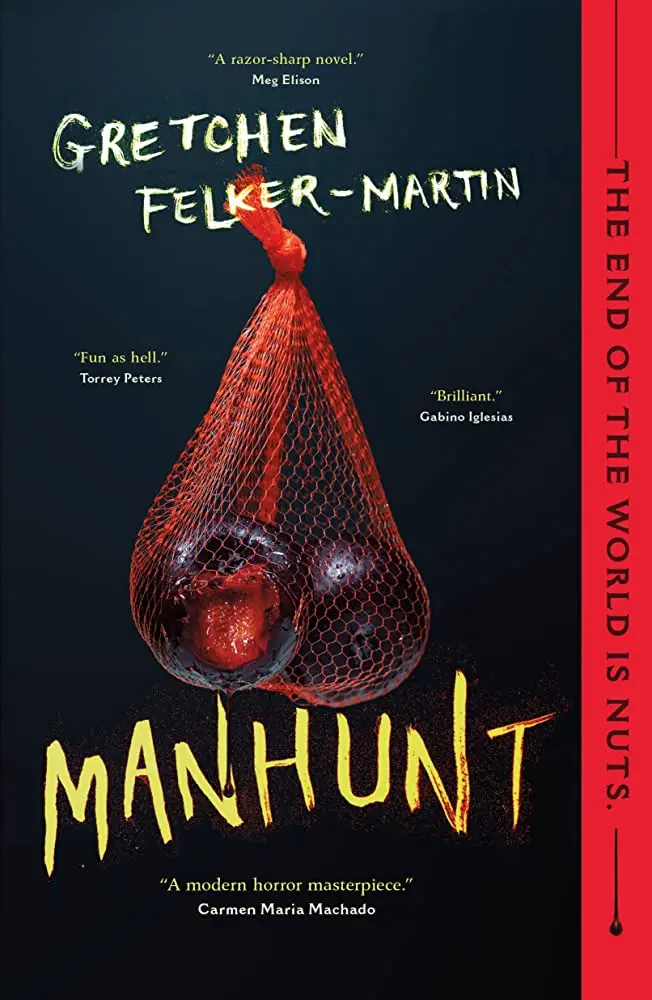

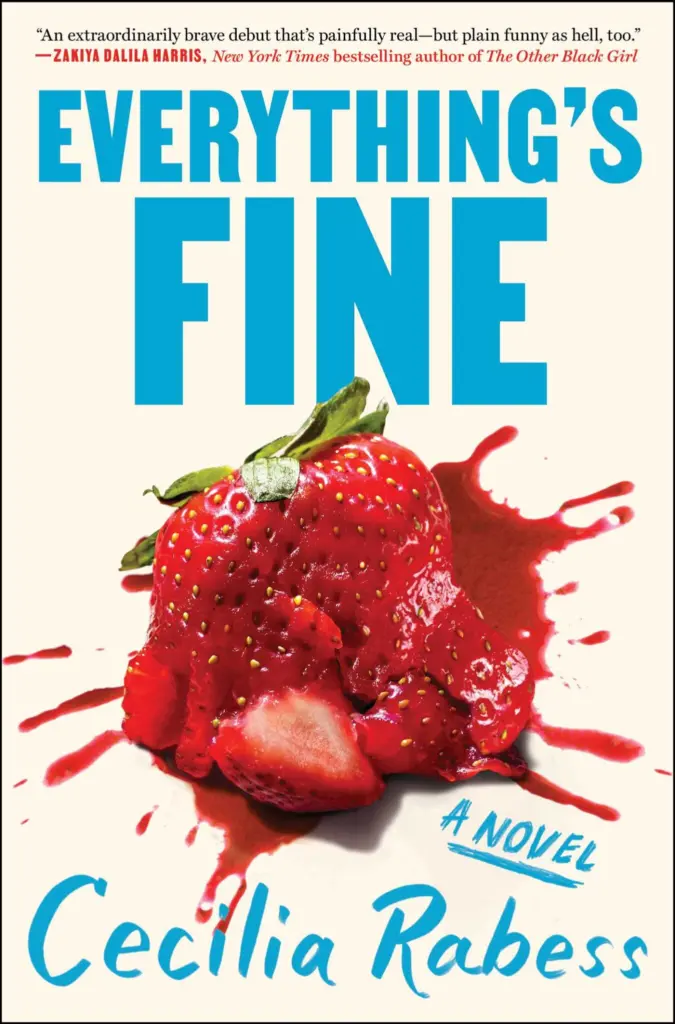

Since 2017, these trends in online literary behavior have extended from the YA space to publishing more broadly. Three recent examples, Elizabeth Gilbert’s The Snow Forest, Cecilia Rabess’s 2023 debut novel Everything’s Fine, and Gretchen Felker Martin’s 2022 sci-fi horror book Manhunt were all targeted by review-bombing. In all three cases, one-star reviews began pouring in before the books were published, with critics objecting to the books’ premises—a story set in Russia, a story about a Black woman who falls in love with a conservative white coworker, and a story about a virus that targets trans people, respectively. In each case, critics objected to the presumed content rather than provide insights gleaned from reading the book themselves.

At its most extreme, review-bombing can keep a book from being published altogether. But even when a book does get published, the impact of such targeted pile-ons can reverberate for the author and readers. Rabess feared that the strafing of review-bombs six months before publication would devastate her novel’s reception once it hit shelves. “I was concerned about the risk of contagion and that readers and reviewers would dismiss the work without ever really engaging with it,” she told The New York Times. “I felt particularly vulnerable as a debut author, but also as a Black woman author.”38Alexandra Alter and Elizabeth Harris, “How Review-Bombing Can Tank a Book Before It’s Published,” The New York Times, June 26, 2023, nytimes.com/2023/06/26/books/goodreads-review-bombing.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare Both Rabess and Felker Martin also reported experiencing direct harassment and personal attacks as part of the backlash against their books.

At their best, sites like Goodreads function as channels for engagement and debate, driving sales and helping authors reach new audiences. But when they are used to pressure authors to change or pull their books, or to demand that readers avoid certain books altogether, users can chill the space for disagreement and unorthodoxy and discourage writers from taking chances in their work. Such public policing of literature risks snuffing out complexity and explorations of moral ambiguity. Xochitl Gonzalez, author of the New York Times best seller Olga Dies Dreaming, shared her concerns with how stories with characters from unsympathetic backgrounds were receiving public backlash that could lead to cancellations, saying, in an interview with PEN America: “Humanizing bad people is part of literature. . . . We’re the only art form left that’s allowed to have nuance.”39PEN America interview with Xochitl Gonzalez

Review-bombs are unique to the digital age, when the virality, reach, and volume of speech can itself have a censorious effect. Criticism of books is itself protected speech, a vital part of any public dialogue about a specific work. Yet the pile-on nature of online reviewing culture creates a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, one that at its most pronounced can threaten to narrow the space for creative expression and impair the freedom to write and read.

As PEN America CEO Suzanne Nossel has said, “You can dismantle the barriers to publication for some without erecting them anew for others.” The conflation of the need for wider literary representation and strict litmus tests for the legitimacy of authorial voice—two related but distinct issues—threatens to do a disservice to both.

#OwnVoices Meets the Identity Trap

At a time when publishing is—rightly—under intense pressure to uplift the voices of writers of color and others with marginalized identities, the literary community has also been engaged in conversations about who has the authority and credibility to tell what stories. These conversations affect both fiction (what perspectives authors can write from) and nonfiction (what subject matter they can address.)

Movements like #OwnVoices are at the forefront of this conversation. When writers with marginalized identities create characters and stories that share those identities, they may incorporate nuances that come from their own experiences. Their authorship also ensures that writers from diverse communities profit from the expanding audiences for such stories.

But for some supporters of the movement, the hashtag has transformed from an entreaty to an inviolable edict. In May 2018, YA author and Book Twitter frequenter Kosoko Jackson tweeted: “Stories about the civil rights movement should be written by black people. Stories of suffrage should be written by women. Ergo, stories about boys during horrific and life changing times, like the AIDS EPIDEMIC, should be written by gay men. Why is this so hard to get?”40Kat Rosenfeld, “What is #OwnVoices Doing to Our Books?” Refinery29, April 9, 2019, refinery29.com/en-us/2019/04/228847/own-v Books that run afoul of these constraints, critics say, risk causing irreparable damage. Little Feminist, a book subscription service for diverse children’s books, explicitly outlines “The Harm of Non-Own Voices Stories”: on its website: “At best, books not created by Own Voices authors and/or illustrators leave out nuances and may inaccurately capture cultural elements. . . . At worst, books not created by Own Voices authors and/or illustrators may perpetuate White Supremacy characteristics and harmful stereotypes.”41Shuli de la Fuente-Lau, “What Does Own Voices Mean? And Why It Matters,” Little Feminist, February 22, 2021, littlefeminist.com/2021/02/22/what-does-own-voices-mean/

There is no inherent contradiction between the belief that the publishing industry must transform to afford greater opportunities to authors from historically excluded backgrounds and the notion that writers must be unconstrained in their choice of subject matter. As PEN America CEO Suzanne Nossel has said, “You can dismantle the barriers to publication for some without erecting them anew for others.” The conflation of the need for wider literary representation and strict litmus tests for the legitimacy of authorial voice—two related but distinct issues—threatens to do a disservice to both.

Any teacher, any student, any reader, any writer, sufficiently attentive and motivated, must be able to engage freely with subjects of their choice. That is not only the essence of learning; it’s the essence of being human. . . . Social identities can connect us in multiple and overlapping ways; they are not protected but betrayed when we turn them into silos with sentries.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

This burden of representation can unexpectedly fall on members the very communities that movements like #OwnVoices seek to elevate, forcing them to reveal aspects of their identity that they might not have otherwise chosen to make public. In 2020, for example, Becky Albertalli—the YA author of Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda, which inspired a movie and a Netflix series centering LGBTQ+ characters—came out as bisexual. A major motivator for her decision to come out, she explained, was the pressure she had faced from the YA community as an apparently straight author writing LGBTQ+ characters. In an essay, Albertalli wrote:

To me, it felt like there was never a break in the discourse, and it was often searingly personal. I was frequently mentioned by name, held up again and again as the quintessential example of allocishet42Allocishet = Allosexual [someone who regularly experiences sexual attraction], Cisgendered, Heterosexual inauthenticity. I was a straight woman writing shitty queer books for the straights, profiting off of communities I had no connection to. . . . Apparently it was obvious from my writing. Simon’s fine, but it was clearly written by a het. You can just tell. Her books aren’t really for queer people.43Becky Albertalli, “I know I’m late,” Medium, August 31, 2020, medium.com/@rebecca.albertalli/i-know-im-late-9b31de339c62 (Italics original)

Albertalli took pains to note that she “believe[d] in the vital importance of #Ownvoices stories.” but added, “I don’t think we, as a community, have ever given these discussions the care and nuance they deserve.” And she made the coerced nature of her announcement clear: “This isn’t how I wanted to come out. This doesn’t feel good or empowering, or even particularly safe. Honestly, I’m doing this because I’ve been scrutinized, subtweeted, mocked, lectured, and invalidated just about every single day for years, and I’m exhausted.”44Becky Albertalli, “I know I’m late,” Medium, August 31, 2020, medium.com/@rebecca.albertalli/i-know-im-late-9b31de339c62

Albertalli may be the most high-profile example of social media pressure forcing this type of self-disclosure, but she’s not the only one. YA author Veronica Roth’s 2016 novel, Carve the Mark, about two clashing fictional societies in a sci-fi setting, was criticized as insensitive to both people of color and disabled people. Critics argued that the main character’s magical power—the ability to cause herself and others pain with just a touch—was ableist, in that it made the character’s relationship to pain her defining trait. In response, Roth revealed that she herself suffered from chronic pain, though writers noted that she was clearly uncomfortable disclosing it.45S.e. smith, “Personal connection: #OwnVoices, Outing, and the Ongoing Quest for Authenticity,” Bitch Media, October 14, 2020, bitchmedia.org/article/own-voices-outing-authors-credibility; Nancy Churnin, “Frisco-bound Veronica Roth talks about diverging from ‘Divergent,’ The Dallas Morning News, April 12, 2018, dallasnews.com/arts-entertainment/books/2

Fantasy writer Leigh Bardugo, author of The Ninth House, told interviewers in 2019 that she felt “disturbed” by the expectation that she had to reveal her own history as a sexual assault survivor to write about sexual trauma. “I don’t believe that I should have to put that on display to justify writing a novel,” she declared. “I’m disturbed by the performances we require of women authors.”46Zan Romanoff, “Leigh Bardugo’s Book About Yale’s Secret Societies will “F*ck You Up A Little,” Bustle, October 9, 2019, bustle.com/p/leigh-bardugo-wants-ninth-ho

In a 2020 interview, Corrine Duyvis expressed dismay at what her hashtag had wrought in some segments of the literary world. “Regretfully,” she told Bitch Media, #OwnVoices “is regularly weaponized against marginalized authors. I’ve seen this happen along pretty much every imaginable axis of marginalization, and I absolutely hate that a hashtag that’s supposed to uplift marginalized authors is being used to police and pressure them.”47S.e. smith, “Personal connection: #OwnVoices, Outing, and the Ongoing Quest for Authenticity,” Bitch Media, October 14, 2020, bitchmedia.org/article/own-voices-outing-au

PEN America’s report Reading Between the Lines found that the norms of the publishing industry force many marginalized authors into a kind of “identity trap,” siloing them into writing not just about their identity but about specific narratives of their identity that align with reader expectations.48James Tager and Clarisse Rose Shariyf, “Reading Between the Lines: Race, Equity, and the Publishing Industry,” PEN America, October 17, 2022, pen.org/report/race-equity-and-book-publishing/; Kat Rosenfeld, “What is #OwnVoices Doing to Our Books?” Refinery29, April 9, 2019, refinery29.com/en-us/2019/04/228847/own-vo Often, these narratives revolve around collective trauma: A Black writer, for example, may be expected to write about slavery or segregation, while a Colombian writer may be expected to write about migration or the effect of narco-trafficking on their community. In pushing marginalized authors to stick to the “correct” portrayals and topics, this identity trap leaves little room for a writer’s individual experiences, for the full diversity of opinions and experiences within an identity group, or simply for creativity itself. Ironically, movements like #OwnVoices have developed in part as a response to these pressures.

The imperative to write only from one’s identity reinforces the identity trap, flattening the experiences of various groups. At a 2022 PEN America panel, Ayad Akhtar, a Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright and PEN America’s current president, expressed concern that his own writing, which includes “critique of [his] American-Muslim, Pakistani-Muslim community,” could, in the future, be eschewed by publishers for its failure to subscribe to monolithic expectations of diverse literature.49Cathy Young, “The Power of Words and the Need to Protect Free Speech,” The Bulwark, September 20, 2022, thebulwark.com/the-power-of-words-and-th

These concerns have caused some in the literary community to reevaluate how they advocate for diversity in literature, to avoid imposing identity essentialism on authors. In June 2021, the literary organization We Need Diverse Books announced that it was jettisoning the term #OwnVoices, pledging to stop using it going forward and even removing it from previous blog posts. Explaining this decision, the organization wrote that using #OwnVoices as a “catch all” phrase “raises issues due to the vagueness of the term, which has then been used to place diverse creators in uncomfortable and potentially unsafe situations. It is important to use the language that authors want to celebrate about themselves and their characters.”50Alaina Lavoie, “Why We Need Diverse Books Is No Longer Using the Term #OwnVoices,” We Need Diverse Books, June 6, 2021, diversebooks.org/why-we-need-diverse-bo

The problem with policing the relationship between an author’s personal identities and their subject matter goes far beyond subjecting members of marginalized groups to unwanted self-exposure. An author’s habitation and exploration of a world other than their own is the very essence of literary creativity. Part of the wonder of literature is imagining how an author can possibly conjure a historical period gone by, a futuristic universe, a character utterly unlike themself, a setting they have never experienced, or a social context that they discover through nonfiction immersive reporting. When an author persuasively renders such stories, the result is inspiration, pushing us as readers to see beyond the limitations of our own lives by experiencing and appreciating the vantage points of others, whether in art or in daily life. To suggest that authors must delimit their imaginations to conform to social expectations or preconceived notions of how particular communities must be portrayed impairs the role of literature to transcend and expand the bounds of both writers’ and readers’ experiences.

The acclaimed novelist Arundhati Roy has taken aim at sentiments that seek to confine authors to writing exclusively about their own experiences, saying in a March 2023 speech at the Swedish Academy:

Sealing ourselves into communities, religious and caste groups, ethnicities and genders, reducing and flattening our identities and pressing them into silos precludes solidarity. . . . Once this maze of tripwires has been laid, almost nobody can pass the test of purity and correctness. Certainly, almost nothing that was once thought of as good or great literature. Not Shakespeare, for sure. Not Tolstoy. Leave aside his Russian imperialism, imagine presuming he could understand the mind of a woman called Anna Karenina. Not Dostoevsky, who only refers to older women as “crones.“ By his standards I’d qualify as a crone for sure. But I’d still like people to read him.51Arundhati Roy, “Approaching Gridlock: Arundhati Roy on Free Speech and Failing Democracy,” LitHub, March 24, 2023, lithub.com/approaching-gridlock-arundhati-r

Akhtar has been similarly critical of this newly ascendant argument that writers must stick to their own experiences. At the 2022 PEN panel, he asked: “Do we really believe that the harm of appropriation is greater than the benefit of artistic empathy? Isn’t the artist’s magical self-insertion into the lives of others the very act of moral and aesthetic enlargement that defines what is most singular and necessary about literature and which is only possible through freedom, this singular freedom of the artist to imagine widely, to imagine completely without fetters?”52Cathy Young, “The Power of Words and the Need to Protect Free Speech,” The Bulwark, September 20, 2022, thebulwark.com/the-power-of-words-and-the

At the 2021 PEN America Literary Gala, Henry Louis Gates Jr., the celebrated Harvard professor and literary critic, spoke in defense of the freedom to write and imagine: “The idea that you have to look like the subject to master the subject was a prejudice that our forebears—women seeking to write about men, Black people seeking to write about white people—were forced to challenge. . . . Any teacher, any student, any reader, any writer, sufficiently attentive and motivated, must be able to engage freely with subjects of their choice. That is not only the essence of learning; it’s the essence of being human. . . . Social identities can connect us in multiple and overlapping ways; they are not protected but betrayed when we turn them into silos with sentries.”53Henry Louis Gates Jr., “Henry Louis Gates Jr. on Literary Freedom as an Essential Human Right,” The New York Times, October 12, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/10/12/books/review/freedom-literary-expression-henry-louis-gates.html

Zero Sum: Which Books and Authors Get Published

In many of these controversies, critiques of specific books often shade into critiques of broader publishing inequities that continue to center white and male writers. Frequently, critics point to certain books or authors as emblematic of enduring, institutional inequities in publishing that determine who and what is elevated.

“Often, frustration about a book isn’t just about that book,” wrote writer and YouTube creator Molly Templeton in a 2019 Buzzfeed essay entitled YA Twitter Can Be Toxic, But It Also Points Out Real Problems. “It’s about the many books like it that readers have already seen. It’s about a desire that all kids see themselves represented in books. It’s about ongoing frustration with an industry that gives lip service to diversity but remains overwhelmingly white.”54Molly Templeton, “YA Twitter Can Be Toxic, But It Also Points Out Real Problems,” Buzzfeed News, June 24, 2019, buzzfeed.com/mollytempleton/ya-twitter-books-publishing-amelie-wen-zhao-social-media

These frustrations can also be tied to the increasing consolidation and corporatization of the publishing industry, in which only five publishers—the Big Five—control over 80 percent of the trade publishing sphere. For the average reader, what these publishers promote becomes the stand-in for the industry as a whole.

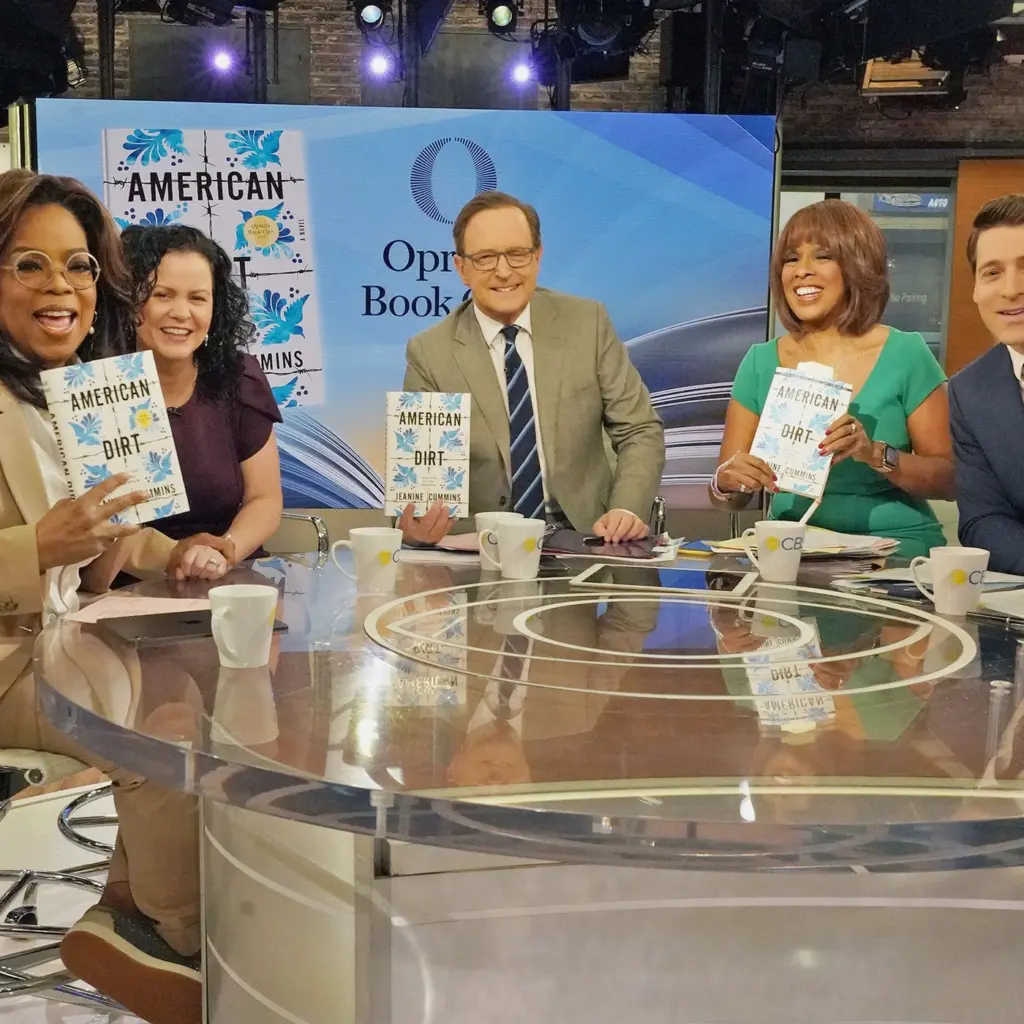

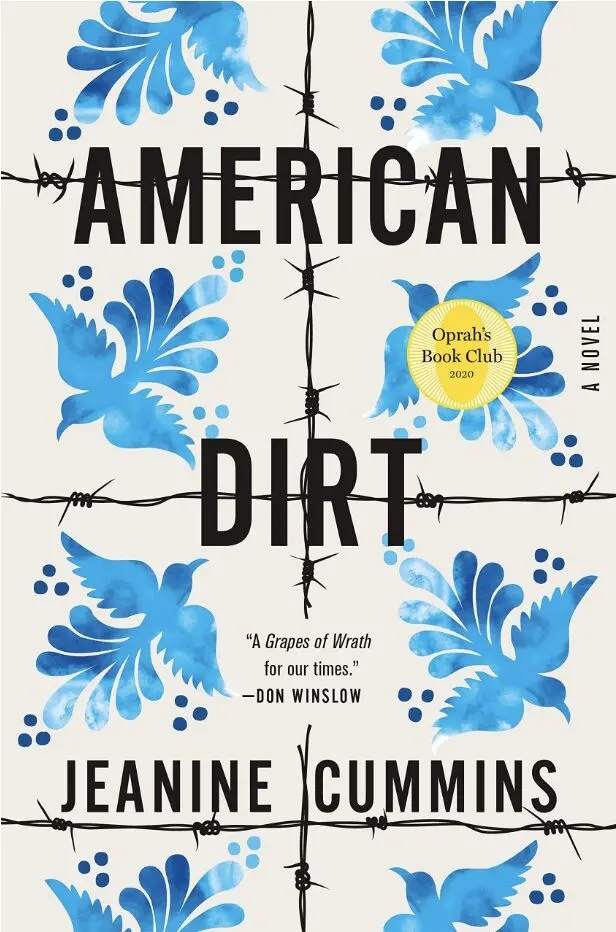

Perhaps the most recognizable example of a book roiled by controversy over representation is American Dirt, by Jeanine Cummins. Published in 2020 and an Oprah’s Book Club pick, the book received significant public criticism after an online review by author Myriam Gurba accused Cummins of two-dimensional depictions of Mexican migrants, allegations that—for Gurba and some others—were linked to Cummins’s non-Mexican identity (she has one Puerto Rican grandparent and three who are white).55Parul Sehgal, “A Mother and Son, Fleeing for Their Lives Over Treacherous Terrain,” The New York Times, January 17, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/01/17/books/review-american-dirt-jeanine-cummins.html; Lauren Groff, “‘American Dirt’ Plunges Readers into the Border Crisis,” The New York Times, January 19, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/01/19/books/review/american-dirt-jeanine-cummins.html; Myriam Gurba, “Pendeja, You Ain’t Steinbeck: My Bronca with Fake-Ass Social Justice Literature,” Tropics of Meta,” December 12, 2019, tropicsofmeta.com/2019/12/12/pendeja-you-aint-steinbeck-my-bronca-with-fake-ass-social-justice-literature/ In a review for The New York Times, Parul Sehgal noted what she viewed as Cummins’s objectifying, “outsider” gaze, typified by “a strange, excited fascination in commenting on gradients of brown skin.”56Parul Sehgal, “A Mother and Son, Fleeing for Their Lives Over Treacherous Terrain,” January 17, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/01/17/books/review-american-dirt-jeanine-cummins.html Esmeralda Bermudez, a staff writer at the book’s Los Angeles Times, observed a reliance on stereotypical metaphors for “danger” and the stilted use of Spanish phrases.57Esmeralda Bermudez, “Commentary: ‘American Dirt,’ is what happens when Latinos are shut out of the book industry,” January 24, 2020, latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2020-01-24/american-dirt-book-latino-response

Some criticism focused on the large advance and hefty promotional budget, honing in on the difficulties faced by Latino authors in securing comparably high-paying contracts. Critics also faulted the publisher, Flatiron Books, an imprint of Macmillan, for insensitive marketing—for example, hosting an author dinner that featured barbed-wire centerpieces, a move that was lambasted as making a marketing aesthetic out of immigrant trauma.58Myriam Gurba Serrano, “At an #AmericaDirt party, guests dined while BARBED WIRE CENTER PIECES adorned the tables,” Twitter, January 22, 2020, twitter.com/lesbrains/status/1219985319648301056

The book had its defenders, including from the Latino community. Prominent author Sandra Cisneros called it “the great novel of las Americas.” Yet as the controversy grew, critics appeared to outnumber supporters.59Dorany Pineda, “As the ‘American Dirt’ backlash ramps up, Sandra Cisneros doubles down on her support,” Los Angeles Times, January 29, 2020, latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2020-01-29/sandra-cisneros-breaks-silence-american-dirt More than 80 writers signed an open letter calling on Oprah to withdraw her choice of American Dirt as a book club pick. The signatories wrote: “Good intentions do not make good literature, particularly not when the execution is so faulty, and the outcome so harmful. . . . This is not a letter calling for silencing, nor censoring. But . . . we believe that a novel blundering so badly in its depiction of marginalized, oppressed people should not be lifted up.”60“Dear Oprah Winfrey: 142 Writers Ask You to Reconsider American Dirt,“ Lithub, January 29, 2020, lithub.com/dear-oprah-winfrey-82-writers-ask-you-to-reconsider-american-dirt/

Amid the uproar, the publisher canceled Cummins’s book tour, citing “threats of physical violence” against Cummins and her bookstore hosts.61Claire Kirch, “Citing ‘Peril,’ Flatiron Cancels ‘American Dirt’ Tour, Apologizes for ‘Serious Mistakes,’ Publishers Weekly, January 9, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/82288-citing-peril-flatiron-cancels-american-dirt-tour-apologizes-for-serious-mistakes.html; Stephanie K. Baer, “The “American Dirt” Book Tour Has Been Canceled Due to Safety Concerns as Critics Lash Out,” Buzzfeed News, January 29, 2020, buzzfeednews.com/article/skbaer/american-dirt-book-tour-canceled Flatiron released a statement saying, “The discussion around this book has exposed deep inadequacies in how we at Flatiron Books address issues of representation, both in the books we publish and in the teams that work on them.”62Claire Kirch, “Citing ‘Peril,’ Flatiron Cancels ‘American Dirt’ Tour, Apologizes for ‘Serious Mistakes,’ Publishers Weekly, January 9, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/82288-citing-peril-flatiron-cancels-american-dirt-tour-apologizes-for-serious-mistakes.html According to a source who requested anonymity, Flatiron staff had extensive internal discussions about their public response—including whether they should issue a public apology or stand by the book.63PEN America interview with former editor at multiple Big Five publishing houses. The source noted that American Dirt’s economic success despite the criticism—the book spent 36 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list—figured into these discussions.64Pamela Paul, “The Long Shadow of ‘American Dirt’” The New York Times, January 26, 2023, nytimes.com/2023/01/26/opinion/american-dirt-book-publishing.html

In conversations with interviewees, American Dirt came up repeatedly as an example of the shifting consensus around racial representation that publishers are increasingly considering in their decision-making before and after publication. Interviewees stressed that the book was a bellwether illustrating how a social media outcry can shift the conversation about a book, pressuring publishers to respond. Despite the book’s commercial success, the episode left many within the literary world with the impression that books perceived to trespass across racial or cultural lines could be risky and undesirable. “Certainly,” said a former editor at a Big Five publisher, “the American Dirt controversy brought up a lot around the idea of, ‘Are we saying that not anyone can write any story? Do you have to have a certain identity?’ There’s a lot of fear around that.”65PEN America interview with former editor at multiple Big Five publishing houses.

Individual authors can bear the brunt of criticisms applicable to an entire industry. “In the end, the real fight over ‘American Dirt’ is not about this writer,” Bermudez wrote in the L.A. Times. “It’s about an industry that favors her stories over ones written by actual immigrants and Latinos.”66Esmeralda Bermudez, “Commentary: ‘American Dirt,’ is what happens when Latinos are shut out of the book industry,” Los Angeles Times, January 24, 2020, latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2020-0 But for commentators pushing for diversity in the literary world, such controversies offer opportunities to force their concerns onto the agenda, and elicit responses that could lead to structural change.

What makes this issue so confounding is that there are different strands of criticism of such books that are often intertwined. There is the essentialist view that a particular identitarian pedigree is a precondition to writing certain subjects. This view can originate from the position that no one is capable of rendering a story that does not conform to their own life experience, and/or the notion that to do so is to steal away an opportunity that should rightfully belong to someone more deserving. Then there is a more subtle view, which holds that while there should be no hard-and-fast rules dictating who can and cannot address which topics, authors who lack the proper identity credentials have a propensity to misportray the communities and characters they depict.

“White authors—you just can’t write these books,” one blogger argued, giving voice to the essentialist view. “’Can’t’ as in you shouldn’t write these books, because they should be told by people of color, but also because you’re simply unable to write them without them being problematic. . . . You’re taking seats from tables, because publishing is racist.”67Jo, “White Authors, Stop Writing Cultural Appropriation,” Once Upon a Bookcase, accessed July 31, 2023, onceuponabookcase.co.uk/2019/04/white-au

YA author L.L. McKinney, who in 2020 kicked off the #PublishingPaidMe movement on literary Twitter to highlight racial discrepancies in author advance payments, made a somewhat similar argument focusing on white authors’ fictional examinations of racism. In a now-deleted 2017 tweet, McKinney posited: “In the fight for racial equality, white people are not the focus. White authors writing books like #TheContinent or #TheBlackWitch, who say it’s an examination of racism in an attempt to dismantle it, you. don’t. have. the. range.”68See e.g. Patricja Okuniewska, “Social Media is Blowing Up Over Problematic Young Adult Novels,” Electric Lit, August 8, 2017, electricliterature.com/social-media-is-blowin

Others, advancing a more textured critique, contend that they are insisting merely that authors write about characters with different identities well. Chicano writer David Bowles, a critic of American Dirt, tweeted: “Nothing wrong with a non-Mexican writing about the plight of Mexicans. What’s wrong is erasing authentic voices to sell her inaccurate cultural appropriation for millions.”69David Bowles, “Nothing wrong with a non-Mexican writing about the plight of Mexicans …” Twitter, January 21, 2020, twitter.com/DavidOBowles/status/121963725 Columnist Nesrine Malik advanced a similar argument in The Guardian, writing:

“The problem isn’t that Cummins wrote a story that wasn’t hers to tell, but that she told it poorly, in all the classic ways a story is badly told. Two-dimensional characters, tortured sentences, an attempt to cover the saga of a migrant without even addressing the wider context of migration or inequality. . . . Money is poured into novels such as American Dirt at the expense of other works that tell stories about Mexicans or migrants that are more accurate, more nuanced but most importantly, far more interesting to a reader who the shallow world of publishing assumes is chronically unsophisticated.”70Nesrine Malik, “American Dirt’s problem is bad writing, not cultural appropriation,” The Guardian, February 3, 2020, theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/feb/0

Bermudez and other Latino writers and commentators also balked at Cummins’s seven-figure advance. In the months following American Dirt’s release, a spreadsheet created by the #PublishingPaidMe movement cataloged that just two Latino writers reported receiving advances of $100,000 or more—compared with 78 white authors who reported the same.71James Tager and Clarisse Rose Shariyf, “Reading Between the Lines: Race, Equity, and the Publishing Industry,” PEN America, October 17, 2022, pen.org/report/race-equity-and-book-publishing/

Yet even with these more thoughtful critiques, making individual books and authors the poster children for systemic inequities inevitably skews the discourse. Cases like American Dirt don’t exist in a vacuum. The reaction to them reflects frustration with the racial disparities that continue to plague the publishing industry, particularly regarding whose stories and voices win fame and money. But when each book becomes a referendum on how well the publishing industry is doing in overcoming its legacy of white dominance, publishers may be tempted to avoid greenlighting any future volume that might play into the hands of critics. Moreover, the notion that certain readers get to adjudicate whether a book meets a particular standard of quality or gets the story “right” overlooks that literary judgments are subjective.

In Reading Between the Lines, PEN America argued that diversifying the ranks of the publishing industry—and of books published—will require a sustained, organization- and industry-wide effort that extends beyond simply hiring a new cohort of editors of color. For an industry that remains overwhelmingly white both in its composition and in the books that it chooses to publish and promote, criticisms and protests that highlight the racial blind spots of authors and publishers are not only protected free speech but can play a vital role in pushing the industry toward progress.

Marketing and Identity

One specific way in which publishers can defend against overly prescriptive critiques is to re-evaluate the ways in which they portray books by authors from particular backgrounds. Publicists should be wary of casting any book as offering a singular, authoritative representation of a cultural group or experience.

When it came to American Dirt, the publisher’s decision to feature motifs of immigrant trauma at a marketing event was not just a one-off mistake. “With American Dirt, Macmillan marketed it as a tale about Mexican immigration, when it was really more of a crime novel,” opined Mary Rasenberger, head of the Author’s Guild, in comments to PEN America.72PEN America interview with Mary Rasenberger, February 2023. In its statement responding to the controversy, Flatiron admitted to “serious mistakes in the way we rolled out this book,” adding that in particular, “we should never have claimed that it was a novel that defined the migrant experience.”73Claire Kirch, “Citing ‘Peril,’ Flatiron Cancels ‘American Dirt’ Tour, Apologizes for ‘Serious Mistakes,’ Publishers Weekly, January 9, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/82288-citing-peril-flatiron-cancels-american-dirt-tour-apologizes-for-serious-mistakes.html

Bad and Boujee: Toward a Trap Feminist Theology, a 2022 book about Black feminism by a white academic, also came under fire after its release (it was eventually withdrawn from publication, a publisher response that we explore further in Part III of this report). The book’s cover, a profile photo of a young Black woman, added fuel to the controversy. It left some who viewed it with the impression that the book was written by a Black woman, which left prospective readers feeling misled when they learned of the author’s identity.

Marketing stumbles can occur as early as the first announcement of a new book. PEN America spoke with two authors whose contracts were withdrawn after social media portrayed their books as racially insensitive in response to advance information released by the publishers. Both authors, speaking to PEN America on the condition of anonymity, expressed the belief that different marketing decisions could have reshaped their books’ reception and potentially enabled publication to proceed.

In Reading Between the Lines, PEN America found that diversity in marketing teams often lags behind the editorial side. More diverse editorial and publicity staff in publishing houses may help to provide less fuel for social media fires and minimize unanticipated consequences.

Definitions of harm are unavoidably subjective and cannot be the basis to deny access to books that would otherwise be accessible.

Literature and the Language of Harm

Many of the harshest critiques of specific books invoke the language of harm.

“There have been countless times where an author’s writing harmed me, simply because they were too ignorant about the struggles PoC face and also re: mental illnesses,” one reviewer wrote in 2017, criticizing several books for conventions like the “white savior” trope” shortly after explaining that “I really wanted to highlight the racism of this kind of authors [sic] because we need to stop supporting them and buying their books.”74Scha Zakir, “It’s Raining Racist Authors: Time to Get An Umbrella,” Affinity Magazine, February 21, 2017, affinitymagazine.us/2017/02/21/its-raining-racist-authors-time-to-get-an-umbrella/ (emphasis original)

Writing in 2019, another YA blogger argued that “if you know those books/the author is problematic, in my opinion, you should not be talking about them. . . . You shouldn’t be raving about them, posting photos of them, declaring your love for them from the rooftops. Yes, those books may personally mean a lot to you. Those books may have got you through a hard time. No-one is taking those books away from you, and no-one is telling you, you can’t love them. But if people have been hurt, I really think it’s time to acknowledge that, maybe, and definitely stop talking about them. Stop promoting them.”75Jo, “On Promoting Your Problematic Faves,” Once Upon a Bookcase, accessed July 31, 2023, onceuponabookcase.co.uk/2019/08/on-pro The reviewer went on to list a set of “problematic” books and authors that she felt readers should stop discussing.

At least some of these arguments conflate harm with offense. The two concepts are related; research has shown, for example, that children who internalize pervasive gender or racial stereotypes may suffer damaging effects that potentially last into adulthood.76“Exposure to gender stereotypes as a child causes harm in later life,” Fawcett Society, March 7, 2019, fawcettsociety.org.uk/news/fawcett-research But to presume that anything that causes offense results in harm is specious, and can become a justification for policing literature to eliminate anything objectionable, to anyone. In too many cases, claims of harm are abstract. Allegations are made without an explanation of the precise harm caused or who endured it. Such claims of harm are particularly consequential when they form the basis for calls to remove access to books for all.

Certainly, YA authors and publishers bear a special obligation to consider the wellbeing and development of young readers. Yet labeling a book harmful stigmatizes it, and presumes that it can have only one effect on a diverse group of readers. A book might conceivably cause harm (in the form of upset or retraumatization, perhaps) to one reader but be enlightening, or even simply harmless, to legions of others. Particularly absent any evidence of demonstrable and widespread tangible or measurable damage, claims of harm should not be used as justification to cancel or withhold books.

In recent years, labeling books “offensive,” “harmful,” and in particular “harmful to minors” has emerged as one strategy that lawmakers and book banners have used to translate their censorious demands on educational instruction and materials into law and policy. PEN America’s recent reports on book bans reveal the codification of “harmful materials standards” in multiple states, including Florida, Georgia, and Texas. These vague and overly broad standards extend far beyond federal definitions of obscenity and typically target books on topics like race and sexuality.77Jonathan Friedman, “Banned in the USA: The Growing Movement to Censor Books in Schools,” PEN America, September 19, 2022, pen.org/report/banned-usa-growing-movement-to-censor-books-in-schools/; Olivia Little, “Moms for Liberty is placing right-wing propaganda in public school libraries while continuing its censorship crusade,” Media Matters for America, April 22, 2022, mediamatters.org/critical-race-theory/moms-liberty-placing-right-wing-propaganda-public-school-libraries-while Laws like Georgia’s SB 226 open the door for an individual parent or guardian to unilaterally challenge any book that they allege to have “offensive content” and, if successful, remove the book from school or public libraries entirely.78Itoro N. Umontuen, “Georgia House passes bill that changes way books get banned in schools,” The Atlanta Voice, March 28, 2022, theatlantavoice.com/georgia-house-passes-b

This is not to make a false equivalence: The wave of book banning being engineered by conservative activists and Republican legislators across the country is incomparably farther reaching, more damaging, more lasting, and more systematically threatening to our rights than criticisms of a small set of YA books on Twitter. But an argument that books must be blocked to avoid harming children does risk adding legitimacy to the restrictions being enacted against books that predominantly touch on subjects like race, gender, and sexuality in American schools. The best defense against book banning in schools is not giving any individual citizen or parent the power to restrict books for everybody based on their own particular views. Calls on publishers to edit or scrap a book in which editors, authors, and prospective readers see value, because of claims that it may harm children, can contribute to undermining a bedrock individual freedom.

Some might argue that it is morally right to call for books to be suppressed if they have included “harmful” stereotypes, while rejecting and fighting calls to suppress books that are claimed to be “harmful” for their presentation of race, sex or gender. But these arguments are easily inverted. While we can recognize that there are different motives at work—one an effort to redress historical inequity, the other an effort to erase diverse representation—the reality is that the principle of open access to the widest range of literature is best safeguarded universally. Definitions of harm are unavoidably subjective and cannot be the basis to deny access to books that would otherwise be accessible.

As the Freedom to Read Statement declares: “It is not in the public interest to force a reader to accept the prejudgment of a label characterizing any expression or its author as subversive or dangerous. The ideal of labeling presupposes the existence of individuals or groups with wisdom to determine by authority what is good or bad for others. It presupposes that individuals must be directed in making up their minds about the ideas they examine. But Americans do not need others to do their thinking for them.”79“The Freedom to Read Statements,” American Library Association, accessed July 31, 2023, ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/freedomread

Publishing must encompass the space to publish material that some consider offensive and that may even risk causing harm. Indeed, there is no such thing as a forceful defense of free expression that does not extend to such works. As Salman Rushdie, the novelist and former PEN America president, has put it: “What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.”80Maya Yang, “‘This is shocking’: writers and celebrities horrified by Salman Rushdie attack,” The Guardian, August 12, 2022, theguardian.com/books/2022/aug/12/salma

Sustaining the freedom to write demands a shared responsibility to uphold principles of tolerance, openness, and the acceptance of varied views and perspectives. Individuals and institutions alike need to be thoughtful and deliberate in reacting to books and responding to criticism of them, realizing that the actions they take can influence literary culture as a whole.

The Dangers of Labeling Books Dangerous

Labeling a book dangerous or harmful is both a criticism and an implied call for action to address or prevent the harms the book purportedly poses. As one journalist put it, “Some feel that condemning a book as ‘dangerous’ is no different from any other review, while others consider it closer to a call for censorship than a literary critique.”81Kat Rosenfield, “The Toxic Drama of YA Twitter,” Vulture, August 7, 2017, vulture.com/2017/08/the-toxic-drama-of-ya-

Various interviewees expressed concern about the view that writers should avoid promoting “harm” in their books—with a definition of “harm” that is broad and in flux and that extends to content that offends. They worried that the current focus on harm was prompting writers to self-censor what subjects they explore, opinions they offer, and stories they tell. The result is less room for risk-taking.