Interview: Prudence Peiffer on Finding Community in the Past

Apr. 03, 2024

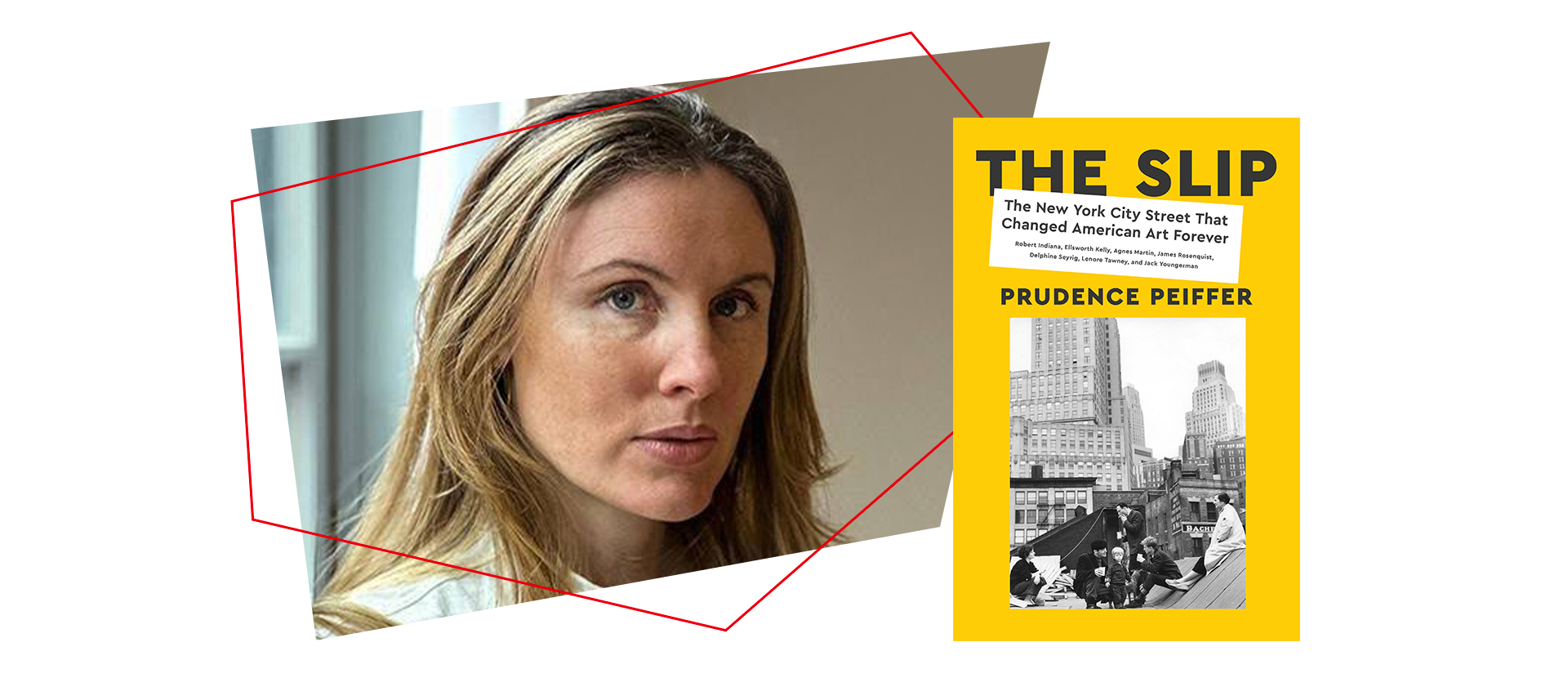

Prudence Peiffer is a seasoned art historian who straddles the worlds of fine art and literature. Her recent book, The Slip, is a testament to that.

Currently the Director of Content at MoMA, Peiffer has an expansive and critical understanding of the art world, which makes her concentrated study of one particular street in mid-twentieth century New York City – the Coenties Slip – deeply intriguing. In The Slip, Peiffer documents the artist colony that sprouted in lower Manhattan between 1956 to 1967 and housed Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Delphine Seyrig, Lenore Tawney, and Jack Youngerman, each in varying stages of their careers.

With such a wealth of knowledge, why, one might ask, has she decided to center on a discussion about a group of artists who found inspiration and sanction in the Coenties Slip for a little over a decade? What can we learn from this tableau of community? In an interview with PEN America, she answers these questions and more regarding the titular Coenties Slip at the heart of her award-winning book, giving insight into her writing and research process. One might easily get lost in the well-spun words of Prudence Peiffer, as her passion and expertise in the arts are matched by her storytelling skills.

Your career trajectory is fascinating. Can you describe your professional background?

As soon as I learned how to read I wanted to be a writer. But it wasn’t until 35 years later when I received an Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers book grant for The Slip that I felt that this was an identity I could claim. I’m trained as an art historian; after a teaching postdoctoral fellowship at Columbia, I went to Artforum magazine as a senior editor. My current day job is Director of Content at the Museum of Modern Art; my team there is responsible for multimedia features around MoMA’s collection, whether videos, long-form podcasts, or commissioned work by poets, scholars, musicians, and artists. So writing is the thing that happens in the very early mornings before my family is up or, if I’m lucky, weekends.

Why Coenties? What gravitated you to that particular time and place?

Well, this story amazed me at every turn, and it’s not well known in the history of postwar modern art. The more I researched the artists who lived at Coenties Slip, including Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Delphine Seyrig, Lenore Tawney and Jack Youngerman, and the broader history of that street, the more the story kept growing. My initial surprise was why such a motley crew of artists, working across very different mediums and approaches–from fiber arts to painting to film–ended up on this obscure little street, living in old sail-making lofts, and making work that would change the course of American art. I didn’t know anything about the fascinating history of Manhattan’s 12 slips, first dug out in the 17th-century, and their central role in the new city. Or the other itinerant communities who lived and worked on Coenties Slip over the centuries. And I realized that this was really a story about the importance of place–how we are shaped by our environment and how it in turn shapes our work.

“I realized that this was really a story about the importance of place – how we are shaped by our environment and how it in turn shapes our work.”

You have written about artists individually in essays and articles, including Agnes Martin who is featured in your book. When did you know you had a full length book with The Slip?

The more I got to know all of the other artists, the more intrigued I was to tell this story. Lenore Tawney and Delphine Seyrig were huge discoveries for me. I felt confident that there was enough material for a full length book when I uncovered the treasure trove of primary source material. Once I learned more about the history of Coenties Slip as a maritime center and marketplace in New York City, starting in the seventeenth century, and the other itinerant communities who stayed there for a time, including sailors and canal boaters, then the woven forms and paintings and drawings and sculptures that these artists produced there started to make so much more sense to me. Their works all had these incredible connections to that place where they were living and the people there who were their lovers, friends, advocates.

I also realized this was a real story about New York during a period of huge destruction and development, especially downtown, which also meant a lot of activism around preserving the city and its architecture. And you see in the manifestos and treatises and laws of that moment, including the Bard Act of 1955 and the Landmarks Law of 1965, and in Jane Jacobs’s extraordinary book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, that people are talking about how important a sense of place is to our lives, not just structures. And so these artists ended up living on this little street that was at the center of extreme socioeconomic, industrial, and political change and debate, at a time just before the explosion of lofts in Soho and the introduction of legislation allowing for artists to live in formerly commercial housing.

So The Slip is a very intimate story that also becomes a bigger history of the city.

“The Slip is a very intimate story that also becomes a bigger history of the city.”

With so much history packed into the book, what was the research process like? What was a typical writing day?

Because I wrote this book in the very, very early hours of the day before work and on weekends, in the height of the pandemic and over the course of three kids being born, there was no typical writing day. Any day that I had more than a snippet of time was a gift. I did some travel for archives and interviews but most of my research was close to home and in great thanks to libraries, online archives, and the digitization services that many libraries and archives offered during the pandemic. Jack Youngerman’s generosity and time over three years of interviews is really at the heart of the book, too. I’m eternally grateful to the people who trusted me with their stories and materials.

While reading your book, the storytelling and style sometimes felt like a traditional novel. Do you read more fiction in your personal life? Was that intentional?

I take this as a huge compliment. I just wanted to tell a good story — to be truthful to the material and to bring in as much detail and texture and presentness as possible. It helps when you have a juicy story. And then the characters that make unexpected appearances, from Herman Melville to Harry Houdini to Anais Nin to Andy Warhol to Robert Moses to even Khrushchev. The structure of the book is very typical of non-fiction though, and I used the maritime slip as an organizing model: the three parts are Arrivals, Getting to Work, and Departures. Nothing stays in one place for long in The Slip.

I do read a lot of fiction in my spare time, and essays. I try to live by Lucy Sante’s credo in a Paris Review interview to read as widely and variously as possible because you never know what’s going to inform your own thinking, way of structuring a book, approach to an idea. I can’t write well if I haven’t been reading–that’s stayed true since I was five.

That’s fascinating! I also love the organizational structure of the book. What has the response been like from readers outside of arts circles and scholarship?

It was important to me to write a book that was as accessible and appealing to a broad audience as possible. You don’t have to be an art historian or museum goer to connect to this story. But I also live in wretched anxiety about anyone actually reading it, a ridiculous contradiction I know but maybe not so unusual for writers. I’ve received some incredible letters; among my favorites have been from artists who felt that the book captured some aspect of the realities of a creative life and labor.

“It was important to me to write a book that was as accessible and appealing to a broad audience as possible. You don’t have to be an art historian or museum goer to connect to this story. But I also live in wretched anxiety about anyone actually reading it, a ridiculous contradiction I know but maybe not so unusual for writers.“

I know you have a history with longform essay publications, but do you see yourself writing another book?

Yes! No turning back now. I’m at the very early hunting and gathering stages for my next project.

That’s so exciting! I love learning art history, especially about American abstract expressionism, which is on the periphery of conversation in this book. What were the most interesting pieces of history you discovered during your research? Any pieces of artwork that had a particular impression on you?

There are so many works of art that came that much more alive for me from my research, including a painting that Ellsworth Kelly made for his then-lover Robert Indiana that involved the shape of a peel from an orange they shared together, or how Andy Warhol came to shoot his film Eat at Coenties Slip. But I think the biggest, continual revelation is the magisterial work of Lenore Tawney; I did not know it well before starting to write The Slip, which is part of a larger omission of textile art from traditional art history. As part of my research, I watched archival film footage shot by Maryette Charleton of Tawney in her sail-making loft, climbing up on the beams to hang her thirteen-feet pieces. Seeing the linen ropes and threads, the sailor knots, the view out her window to the tugboats on the East River–it’s so evocative. I’m very happy to say that Tawney’s work is starting to show up more in exhibitions–even right now in New York, there’s work on view by Tawney at MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Noguchi Museum (also a testament to the long championing of Kathleen Mangan, the Lenore G. Tawney Foundation director).

Ideas of community and place are essential to your book. Do you think the contemporary art scene in New York City has that sense of community and collaborative space?

We’re in a moment where it’s ever more difficult to find a sense of community in our daily physical lives because we’re so tethered to our devices and our online interactions. I do think there’s potential online; it’s a huge part of what I do at MoMA to try to reach audiences around the world. But I’m skeptical that one can achieve online the kinds of connections I’ve been thinking about in The Slip. Because the artists there created a sense of community that was so intimately tied to this physical site and its long history. They were handling its material memory.

Can artists find a place today to live together in Manhattan with water views and space to work for the equivalent of $35 a month in 1957? Probably not. Real estate has left little room for mixed income housing, especially with the recent Rent Guidelines Board rent increase in New York. (In a recent survey of artists by the Downtown Brooklyn Arts Alliance, 75% of responders cited “cost and space” as “primary barriers to creating art in New York.”) But I’m also an optimist. Artists have always been creative in how to make things work, particularly around commercial real estate. (Afterall, the Slip artists were living illegally in their buildings, which were only zoned for commercial use.) To give just one example, the artist-run gallery Parent Company is a shipping container between high rise construction sites in downtown Brooklyn. Its very structure and siting is ephemeral, but it’s all about finding space. And T Magazine recently ran an article about some artist buildings that have “against all odds” survived in New York, including one downtown near the Slip on Fulton Street. So I do have hope. New York is nowhere if it’s not a place where a work of art is always taking shape just down the block.

Wow, thank you for providing this perspective, it’s great to see there is a glimmer of hope for artist communities here. And, perhaps this is cheesy, but if you could be placed on that roof or at the dinner table in 1958 with Seyrig, Clark, Youngerman, Kelly, and Martin, what would you want to ask them?

I love this question and actually no one has asked me before! When I asked Youngerman about what he would talk about with his fellow Slip artists, he said it usually wasn’t about art. It would be amazing to just hear some of those everyday conversations, see where they lead–as I argue in my book, these are the kinds of details that can be more profound than any grand pronouncements or manifestos about art-making. I’d love to talk with Seyrig about women’s rights and being a young mom with an ambition to have a career. I’d ask them what they were currently working on, what other artists they liked or didn’t, what they were reading, listening to, worrying about. What political issues they were most invested in. I know some of these answers already through their incredible journals and letters and my interviews, but it would still be great to be in conversation. I’d also ask if I could tag along on one of their scavenging missions to find materials for their art. There are some lively anecdotes about dinner parties at the Slip involving a lot of whiskey and wine and dancing so I would hope that would be a part of our night.

Myka Greene is Development coordinator at PEN America.