The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week PEN America’s Public Program Manager, Lily Philpott, speaks to Naima Coster, author of Halsey Street, published last year by Little A.

1. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

For me, there’s no separating my identity from my writing. All my preoccupations and questions have been formed by what it’s been like to be myself in this world: black, a woman, Latina, a daughter and granddaughter of immigrants, a New Yorker, among other things.

I wouldn’t dare to say there is a writer’s identity. I suppose we all share some general qualities: writers observe; writers pay attention; writers want to understand. But that’s all very thin. The more I meet other writers, the more I am convinced of how different we all are. This is also true of writers of color who are often lumped together. We have distinct projects, politics, aesthetics. We may share a special solidarity or camaraderie, but the prerequisite for that connection isn’t sameness.

“The more I meet other writers, the more I am convinced of how different we all are.”

2. In an era of “alternative facts” and “fake news,” how does your writing navigate truth? And what is the relationship between truth and fiction?

The truths I’m circling around in my work aren’t dependent on facts; they’re dependent on experience, perspective, where someone is standing. I’m interested in what things mean and not only what they are. Above all in my work, I’m asking questions. What’s it like to become a mother before you’re ready? How do you recover tenderness in a world that has required you to be hard to survive? How does it feel to paint when you love the practice but don’t trust in your own talents? These are sticky questions with no fixed answers. They’re different questions than: Can we observe increases in temperature in the world’s oceans? Are black people in this country disproportionately targeted by police? How many people were present at Trump’s inauguration?

3. Writers are often influenced by the words of others, building up from the foundations others have laid. Where is the line between inspiration and appropriation?

Appropriation usually includes some element of distortion. Perhaps that’s why certain appropriations inadvertently edge on parody. Appropriation capitalizes on a tradition or form. Inspiration requires a kind of reverence for and reference to the original source. It aims to extend, or honor, or enter a tradition. I also want to say, I may be totally wrong about this.

4. “Resistance” is a long-employed term that has come to mean anything from resisting tyranny, to resisting societal norms, to resisting negative urges and bad habits, and so much more. It there anything you are resisting right now? Is your writing involved in that act of resistance?

Whenever I write, I’m asserting that I matter, my mind matters, my pleasure matters. I see that as resistance, even if it only changes what it’s like for me to be in the world. But I also think the care, attention, and depth I give to my characters affirms that they are fascinating, complex people, worthy of our attention, although the world is thick with messages that people like my characters don’t matter: black, Latinx, broke or poor, female, immigrant, living in cities. I don’t write about my characters to make a statement, although I am intentional when I decide who they are. Writers are always choosing who to pay attention to, who to listen to, who to follow.

5. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

I’m not sure I’m qualified to say what ‘the biggest threat’ might be, or, even, that I’m interested in identifying a single threat when there are so many interconnected challenges. I will say, for myself, my right to free expression has often been threatened by white supremacy and patriarchy, and the idea that my belonging or my right to any power is contingent on my being agreeable, intelligent, polished, whatever. This logic attempts to put a limit not only on what I say but how I say it, how I present myself, how I be.

6. What’s the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words?

In Halsey Street, the portrayal of a broken mother-daughter relationship is daring and unsettling. There are so many comforting adages we circulate about the beauty of motherhood, the stability and inviolability of family bonds, the automatic, primal, essential connection between mothers and daughters. It’s puzzling to me because we talk about these relationships as if we don’t find serious abuse in families, as if every mother desired motherhood, as if familial bonds aren’t often made up by hurting people who make mistakes, some grave and irreparable. It’s a nice thing to think and say, ‘Mothers love their daughters,’ or ‘Nothing can break the bonds of family’ but we just have to look at the world, to listen to people, to know that doesn’t reflect everyone’s experience. But it’s much more unsettling to admit, ‘Sometimes parents love their children; sometimes they don’t. Sometimes family isn’t safe. Sometimes home is hard. Sometimes wounds are stubborn, and bonds aren’t repaired.’ I don’t think these possibilities make for a grim world, without light in it, or joy. For some people, to read about a mother and daughter like Mirella and Penelope is affirming or illuminating. It can be hard to find nuanced representations of loss or pain in a culture that insists again and again on erasing, dismissing abuse, neglect, and wrongdoing of all kinds. In a gaslighting culture, it becomes very hard to say, ‘I know this to be true,’ and any little utterance, or work of art, that gives someone permission to say so, becomes all the more important.

7. Have you ever written something you wish you could take back? What was your course of action?

Thankfully, I’ve never published something I wished I could take back, but I plan on writing for a long while, so it’s still a possibility.

8. Post, stalk, or shun: What is your relationship to social media as a writer?

For better or worse, I find myself doing mostly stalking on social media, although I aspire to shun more. I wish I could say the stalking is in some way generative for me, but it isn’t. It’s a time when I shut my brain off.

9. Can you tell us about a piece of writing that has influenced you that readers might not know about?

9. Can you tell us about a piece of writing that has influenced you that readers might not know about?

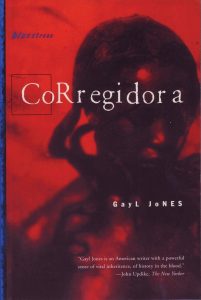

Gayl Jones’s Corregidora was an important book for me when I was in my twenties.

It’s a blues novel, a first novel, about a singer Ursa, reckoning with family legacies of sexual violence, slavery, and questions of genealogy, what we inherit from the women that came before us. I read it as a novel about trauma but also about self-determination, the importance of expressive culture, and music.

10. In an interview with The Paris Review in early 2018, you described a new book project that is a work of speculative fiction. Can you tell us more about the transition between genres? Are you finding that your writing habits are altered? Are you approaching character, plot, themes, etc. in a different way?

I have two book projects that I’m working on right now, one which could be categorized as speculative fiction. I don’t see myself as transitioning between genres, since all of my thematic interests have remained the same: women and family, memory, race, connections across lines of difference, tenderness and ruthlessness. I also find my muscles as a writer are roughly the same across projects, so the same things come naturally, and the same things are hard.

In both novels, one set in North Carolina in the 1990s up until the present, and the other in a dystopian mining town, I have to world build, reckon with history, be mindful of all the things my characters are carrying, how they’re read in the world. In both works, I’m trying to stretch myself in terms of the way time operates, how psychologically close we can get to characters, and how to build a book that is at once deeply internal but also gripping, energetic.