The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Public Programs Manager Lily Philpott speaks with journalist Zahra Hankir, editor of the recently published essay collection, Our Women on the Ground: Essays by Arab Women Reporting from the Arab World (Penguin Books, 2019).

1. What advice do you have for young journalists?

Think big, start small. If you’re job hunting, the role itself should ideally outweigh the allure associated with working for bigger, more mainstream publishers. So try not to limit your search to the NYTs and the BuzzFeeds and the “exotic” foreign reporting gigs; think niche and look local, too. On that note, don’t be deterred by rejection, take feedback gracefully, learn from it, and own up to mistakes.

Stay positive. This is a cut-throat industry that’s difficult to break into (and often difficult to grow in)—especially if you’re from a minority or working-class background—so it’s easy to be disheartened and to reconsider options, particularly amid widespread layoffs and restructuring. But diversity in the newsroom is needed now more than ever, and if you’re passionate and patient enough, keep an open mind and are willing to take risks, you can craft your own (likely nonlinear) career path.

Be versatile and stay curious. Cultivate your digital media skills. Step out of your comfort zone. It’s never too early to start a portfolio, even if it’s a blog post or a piece for your student newspaper. Ask questions. Take notes incessantly, even when you aren’t on assignment. Verify every. single. detail: twice.

Chase your passions and interests. My mentor at Columbia University, the late and great David Klatell, imparted upon me a piece of advice while I was a (nervous) student at the j-school that I’ve continued to cherish over the years, and that speaks to the idea behind this book: Don’t shy away from writing about your community, your people, or your home country or region, so long as you uphold the highest journalistic standards.

2. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I’m drawn to women writers and writers of color who take bold risks in their work, in both style and scope. I’m a fangirl of Azareen Van Der Vliet Oloomi—I was hooked on Fra Keeler and Call Me Zebra for weeks; her essay writing is also divine. I’m eagerly awaiting Hala Alyan’s forthcoming novel, following the magical Salt Houses, which whisked me away from my basement flat in Hackney to the Arab street. And I was knocked sideways by the sheer scope and ambition of Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater and can’t wait to see where their career takes them next. Zeina Hashem Beck is a skilled Lebanese poet whose work I follow closely and adore to no end. As for nonfiction, I’ll devour literally anything penned by Rafia Zakaria and Azadeh Moaveni, who possess intellectual bravery and depth, as well as writing prowess.

3. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

Edward Said, to discuss with him the state of the Arab world and its relationship with the West today, looking in particular at Syria, Palestine, Iraq, Yemen, and Egypt.

4. What is your favorite bookstore or library?

Librairie Antoine in Beirut was my window into great and niche literature while I was a student of political science at the American University of Beirut. Fast forward, in London, I adore and regularly visit my local bookshop and library: Stoke Newington Bookshop and Stoke Newington Library.

“My interest was not so much in the challenges themselves, but rather, how the women felt about and responded to them.”

5. Our Women on the Ground brings together an incredible selection of talented Arabic women journalists, allowing them to tell their stories in their own words. What was the editorial process like for this book? How did you select the contributors and work with them to shape their essays and the themes the collection is organized around (Remembrances, Crossfire, Resilience, Exile, and Transition)?

I’d been following the work of many of these women for years, so I already had several of them in mind. I admittedly looked for women who had experienced some sort of adversity in their reporting, were telling unexpected stories, or were challenged in some way by the regimes they’d been covering. My interest was not so much in the challenges themselves, but rather, how the women felt about and responded to them. I made sure I included a broad range of contributors in terms of their religious and cultural backgrounds: nationalities, ages, ethnicities, and political leanings. My hope was to demonstrate the diversity of the region through their stories. I worked quite closely with almost all of the contributors on shaping their essays, without ever instructing or coaching them on how they should speak their own truths. The point of the collection was to allow them to speak for themselves; indeed, some of the women questioned the very premise of the volume. After short conversations during which the authors identified what they wanted to focus on, I offered suggestions and teased out themes throughout.

It was more challenging to work with the women who were on the field as they wrote, or who’d recently stepped away from it, as it took some time for them to process what they’d witnessed and how they personally felt about it. Some of the women were on the front lines and understandably experiencing trauma; others had stepped away from the field and were understandably still grappling with how to process that trauma. As such, I approached all women and their stories with great sensitivity, at times gently nudging them, at others stepping aside.

I was hyper aware of the difficulties they had to contend with while writing, but also encouraged them to share with the world their thoughts. I have tremendous respect for the manner in which each contributor captured her challenges: some by putting themselves at the center of their chapter, others by writing around their lives through the lens of their sources.

My brilliant editor at Penguin, Gretchen Schmid, offered insights that were incredibly helpful as she approached the collection in the same way a Westerner who knows little about the Middle East might; as a native, I was at times too immersed in and familiar with religious, cultural, and social motifs. We didn’t want to assume too much knowledge on the part of the reader, and also wanted to avoid telling the story of the region within a predominantly basic and stereotypical framework. I think we struck the perfect balance. Specialists will appreciate these stories, as well as those who aren’t at all familiar with the region—the themes are, after all, universal.

Speaking of which, the broader themes were set after all the essays were done and dusted. At that point, after having looked very closely at each essay on a standalone basis, sometimes for months at a time, we took a few steps back and approached the collection as an actual collection with overarching motifs.

6. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

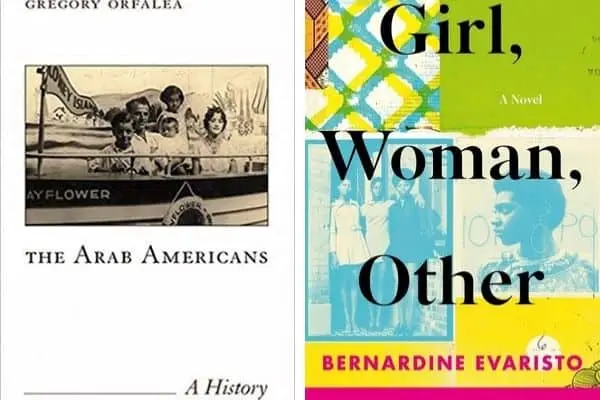

Gregory Orfalea’s The Arab Americans: A History, for a story on New Jersey’s Arab-American community. Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other is next on my list.

7. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I was an introverted, imaginative, and pensive child; I’d often sit for hours in my room reading Frances Hodgson Burnett, Jane Austen and Emily Brontë (my mother was a fan of the latter two authors). Burnett’s A Secret Garden and A Little Princess are the first two pieces of writing that I turned back to again and again. As a young reader—a child, really—the books threw me into a magical, romantic, and fantastical world in which I felt the surreal was within reach; that justice wasn’t only achievable but inevitable; and that against all odds, I would rise above challenges (however minuscule they were at the time), find my own voice, and discover confidence as I came of age. I was, of course, quite naive, and wasn’t exactly thinking of race, class, or privilege at the time, so I’d love to revisit both books to see how I feel about them today! I do hope they’ve aged well.

8. As a journalist, what types of stories are you drawn to, and how do you maintain momentum and remain inspired while working?

I’m drawn to investigative journalism and long-form pieces that immerse the reader in the story and that surprise them or tell them something new about the world or a particular event. (These three recent pieces on incels going under the knife to boost their dating prospects, what really happened to Malaysia’s missing airplane, and what happens to the human body when we come off of antidepressants, come to mind.)

As for maintaining momentum, when I’m writing or editing I tend to isolate myself and to intermittently switch off my Wi-Fi connection till I get the work done. I usually work in bursts of 20 minutes at a time, because I’m so easily distracted. I generally find writing to be an excruciating process. For inspiration I turn to my mother, who perfected English as an immigrant in the UK in the ’80s and ’90s and who now teaches it as a second language to the underprivileged and refugees in Lebanon. She takes such joy in writing, editing, and translating (she incidentally translated three chapters in the book from Arabic to English) and is my editorial inspiration and cheerleader.

9. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

The rise of authoritarian governments, right-wing movements, and internet censorship.

I can’t say my right to free expression has ever directly or overtly been challenged. As a young journalist in Lebanon I enjoyed freedoms many reporters in the region’s media industry do not. I did, however, constantly engage in self-censorship. Though Lebanese media is among the freest in the Middle East, it is politically polarized, and journalists tend to work for media outlets that are government, business, or political party mouthpieces. Threats in particular have as of late been leveled against bloggers and digital journalists. As such reporters tend to understand there are “red lines” that mustn’t be crossed.

10. What is one book or piece of writing by an Arab woman you love that readers might not know about?

“Oranges,” a poem by Iman Mersal (here’s an excellent translation by Khaled Mattawa). Layered, intense, bursting at the seams.

Zahra Hankir is a Lebanese-British journalist who writes about the intersection of politics, culture, and society in the Middle East. Her work has appeared in Vice, BBC News, Al Jazeera English, Bloomberg Businessweek, Roads & Kingdoms, and Literary Hub, among others. She was awarded a Jack R. Howard Fellowship in International Journalism to attend the Columbia Journalism School and holds degrees in politics and Middle Eastern studies.