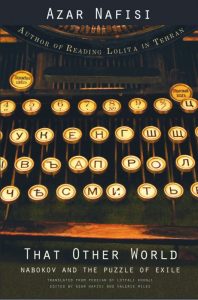

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Lily Philpott speaks with Azar Nafisi, author of That Other World (Yale University Press, 2019).

1. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

An idea, a feeling, something deeply experienced starts within me and doesn’t let go—the kind of experience you have when while walking in the middle of the street you suddenly notice the cars are furiously honking, because you have been too engrossed in your own world to notice the green light. Sometimes after a while that urge disappears, but most of the time it stays, becomes an obsession, demands to be further investigated. I want to know, to understand, so I investigate it through writing, I need to give shape to it, make it concrete, make it articulate. Of course, that is the initial stage, like falling in love at first one is too intoxicated to notice the other matters, the obstacles, the difficulties. Many are the moments when I want to just give up, when I walk around the room, not knowing what I am searching for, when I divert myself from writing, doing almost anything but write. When that happens I read a lot and watch my favorite movies and television series. Somehow these activities make me go away, but not too far, they allow my mind to wander, but always come back. Sometimes I am positive that this time it really won’t work, that I better give up. But then right at that moment of despair, there is often a sudden breakthrough and I am back on the track!

2. How can writers and readers affect resistance movements?

The fact that so many mighty states with such huge unimaginable power would target a group of men and women who literally have nothing more powerful than their words, shows the threat literature and arts present to authoritarian rule. Literature is by nature subversive, always on the side of the individual and freedom of choice. Its main and most dangerous weapon is the truth. In its search for truth, literature going beyond the appearances, reveals what is hidden to the naked eye, clarifies what has been opaque. And we all know how dangerous truth can be. For once we know it, we become a witness and if we remain silent we become complicit, even in crimes committed against us. Literature resists tyranny mainly by refusing to remain silent, by giving voice to the voiceless, the silenced and the suppressed.

“Literature is by nature subversive, always on the side of the individual and freedom of choice. Its main and most dangerous weapon is the truth. In its search for truth, literature going beyond the appearances, reveals what is hidden to the naked eye, clarifies what has been opaque. And we all know how dangerous truth can be.”

3. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I am working on a new book, so most of my reading is a rereading related to that book. I almost simultaneously finished rereading James Baldwin’s essays in The Cross of Redemption and David Grossman’s To the End of the Land—two writers I keep returning to. I also enjoyed reading Samantha Power’s new book, The Education of an Idealist. I look forward to reading Margaret Atwood’s most recent novel, The Testaments and The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women, translated by Dick Davis.

4. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

In my country of birth, Iran, one of the first things the Islamic Republic did was to curtail freedom of expression, they tried it through the laws and through censorship, they did it through threats and spreading fear—for the past forty years defense of freedom of expression and of choice has been at the top of the demands of Iran’s vital civil society. In my other home, America, things are different, people are not jailed, tortured and in some cases murdered as under the Islamic regime. That does not mean freedom of expression is not under threat, especially now in the Trump era. Ray Bradbury says, you don’t have to burn books to destroy a culture, all you have to do is to make people not read them. In America today, freedom of expression is threatened by indifference, by a complacent and conformist culture that does not want to be disturbed, that cannot bear opposition, that does not tolerate difference. I had to fight for my freedom of expression and choice in Iran and on a different level in America I have to fight the indifference, the arrogance rooted in ignorance, the degradation of imagination and ideas on a daily basis.

5. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

5. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

All books are products of certain acts of daring—no matter what you write, if you write honestly you will reveal something very personal about yourself, something you might have hidden even from yourself. There is an element of cleansing and self-cleansing to the act of writing. For this reason it is difficult for me to say what is the most daring thing I have written. Perhaps my memoir, Things I Have Been Silent About. In my country of birth personal memoirs are almost taboo, memoirs are about public deeds and not personal ones. I knew I would get into trouble from some quarters if I write mine. Yet the most difficult challenge was not how others would react, but how I reacted, the fact that writing that book was one of the most painful experiences I have ever had. But I felt I had to write it in order to say a proper goodbye to my parents and my country of birth through remembering them, celebrating them, and mourning them.

As for taking back something I have written, books are like my children, once they are out they have a life of their own, I do not want to have control over them. To say, I wish I had not written a certain piece is like saying I wish this child was not born.

6. What advice do you have for young writers?

I agree with James Baldwin’s response when he was asked a similar question: “Write. Find a way to keep alive and write….If you’re going to be a writer, nothing I can say will stop you; if you’re not going to be a writer, nothing I can say will help you.”

I don’t believe in giving advice. But I can talk about my own writing experience: Writing like all creative processes is similar to falling in love, you don’t exactly know why you feel the way you do, but there is this itch, this urge that keeps you awake at nights and preoccupied during the day, something needs to be articulated, shaped, communicated—the rest is hard work, very hard work.

7. Your most recent book, That Other World: Nabokov and the Puzzle of Exile, was published in English for the first time this summer. What do you think is the reason behind Nabokov’s lasting influence around the world?

Nabokov believed “governments come and go, only the trace of genius remains.” His work is the proof of the veracity of that statement. Like other great writers, Nabokov’s work transcends the boundaries of time and space. He wrote of matters that belonged to a particular time and experience and yet were universal, transcending those boundaries. You remember the famous afterword Nabokov wrote to Lolita? In that he gives us a definition of “aesthetic bliss:” “For me,” he says “a work of fiction exists only insofar as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss, that is a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm.”

The reason Nabokov is enduring is that in his fiction he connects us to others and provides us with “curiosity, tenderness, kindness and ecstasy,” all of which are human traits that stay with us no matter where and when we live.

“Lolita reminds us that monsters don’t appear to us with the words evil written on their foreheads, evil lives among us and is of us, evil is seductive, it comes to us in all guises, in the garb of a sophisticated, poetic man or a man of God, or a successful businessman.”

What Nabokov says about Tolstoy is also true of him: “The decrees of society are temporary ones; what Tolstoy is interested in are the eternal demands of morality.” Nabokov had to flee the country he passionately loved and was fiercely if not in an actively political manner, against the Soviet regime. Yet in his fiction he never directly confronted that regime, nor did he turn his novels into vehicles for political messages—had he done he would have been forgotten by now, like so many authors of his time, Gorky for example or Sholokhov who even won the Noble Prize for literature. Nabokov did something more profound, more subversive and more lasting: He wrote about not just a specific totalitarian regime, but what totalitarian mindsets regardless of time and place target most: individual rights to choice and freedom of expression. From Lolita to his most “political” (political in this case needs quotation marks) novels, Invitation to a Beheading and Bend Sinister, are all focused on a fierce defense of the rights of the individual and celebration of freedom of choice and expression. Lolita, for example, as I mention in my book, like all great novels has many levels, the plot is about the rape of a young teenage girl, but on another level it is about the fact that the greatest crime we can commit—be it on a personal or political level—is solipsism, confiscation of another person’s life and reshaping it according to our own definitions. Humbert takes away from Lolita, her childhood, her future. He is not an Ayatollah Khomeini or a Donald Trump, but he shares with them the attitude, the mentality of a tyrant by imposing his image, his desires and urges on another human being, turning that being into a helpless victim. Lolita reminds us that monsters don’t appear to us with the words evil written on their foreheads, evil lives among us and is of us, evil is seductive, it comes to us in all guises, in the garb of a sophisticated, poetic man or a man of God, or a successful businessman. In whatever guise, evil is always counterfeit, he is not what he seems and claims to be. And last but not least, in Lolita the readers are addressed several times as Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jury. Nabokov holds the readers responsible for the crimes committed by men like Humbert Humbert. Where were we when these crimes were committed? Did we condemn the perpetrator or the victim? Did we differentiate between the perpetrator and the victim? Or were we seduced by the perpetrator, seduced by his promises, by his charm? No matter when and where we live, as readers Nabokov holds us responsible, and that is the reason today he is still read and is still relevant, be it in the United States of America, or the Islamic Republic of Iran.

By the way, you want to know how relevant Nabokov is to Trump era America? Please read Invitation to a Beheading and Bend Sinister.

8. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

I have mentioned many times that when it comes to books and by extension their authors, I am very promiscuous! There are many authors living or dead whom I would like to meet. But since I cannot meet them all, I will pick an imaginary storyteller who to me is very real. I mean one who is the mother of storytelling, namely Shahrazad of the fame. I would like to discuss with her the amazing and miraculous way she shapes the idea of stories as means of resistance and survival, how she uses curiosity and empathy to make the king experience a world different from the black and white one he had constructed for himself—through her stories, Shahrazad manages to make the king see the world in color. I will ask Shahrazad, does she believe stories still have the power to cure all mad kings as well as their subjects and if so, how she will cure those mad kings that rule over us today?

“Writing like all creative processes is similar to falling in love, you don’t exactly know why you feel the way you do, but there is this itch, this urge that keeps you awake at nights and preoccupied during the day, something needs to be articulated, shaped, communicated—the rest is hard work, very hard work.”

9. Why do you think people need stories?

Stories have been with us since time immemorial, they are a way of perceiving the world, experiencing it and changing it. Stories have a very pragmatic role in our lives, they are a way of survival, a way of understanding others as we understand ourselves as both human and humane. They articulate, give shape and make concrete ideas and concepts, feelings and emotions, they make visible what has been invisible. Stories appeal to two basic human traits, traits that help with our survival: the first is curiosity, that insatiable urge to know, to come out of ourselves and try to discover and understand others. This is the basis for both science and literature, science is curious about the natural world and literature about the human psyche, about emotions, and feelings, our attitude towards ourselves and the world—it is about making concrete that which appears to be abstract and inarticulate, which is why stories are metaphorical, working through images. It is through evoking the readers/listeners’ curiosity that they make us experience empathy. Once you are curious about another being you try to know them, to understand them and that knowledge comes through empathy, through recognition of something basic to you in another being. Empathy is the way we connect to others, the way we build communities, the way we realize our differences but at the same time what we share in common. Without that, a world only based on difference becomes a very dangerous place. Difference should be celebrated but it is not enough, we need empathy, the recognition not just of how different we are but how alike, how our own survival depends on survival of others.

10. In your introduction to That Other World, you write about undertones of “defiant mockery” in Nabokov’s work, and the power that comes with acknowledging the absurdity of life under a totalitarian government. Can you speak more about the power of humor and satire in an oppressive situation?

The protagonist in Nabokov’s dystopian novel Invitation to a Beheading, a fellow named Cincinnatus C, is jailed in a nightmarish country where all the citizens are transparent and he is opaque, so he is to be executed for the crime of “gnostic turpitude.” Inside his jail cell, everything is staged, it is a theater prop, complete with a phony spider on the wall. A set of rules are hung on the wall, the most absurd of them all is that the prisoner is forbidden to have illegal dreams. All of this is of course unreal, even surreal, or what I call irreal—we believe we don’t confront such things in real life. Yet whether you live in a totalitarian society like the Islamic Republic of Iran where for a while the chief censor for theater and a television channel was blind, where in the drawings of a children’s book the female chickens wear the veil, or you live in Mr. Trump’s America, where Trump’s every speech, every statement is part of a show, and a lie, you live in a world similar to that of Cincinnatus’s where everything is fabricated, part of a show. What totalitarian mindsets do as Kelly Ann Conway so “honestly” stated, is to create a parallel reality, an alternative reality and present it to us as real. Invitation to a Beheading might be called irreal, unreal, surreal, but it definitely reveals the truth behind and beyond our reality. There is something simultaneously humorous as well as tragic in the absurd. Tragic because this absurdity, this show is real, it is imposed on our reality and we have to accept it as reality as we accept that we have now become figments in someone else’s dream. And this realization on the part of majority of the people is most dangerous to totalitarian mindsets, it blows their cover and reveals them as they are.

Azar Nafisi has taught at the University of Tehran, the Free Islamic University, Allameh Tabatabi, and Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. She is the author of That Other World: Nabokov and the Puzzle of Exile, recently published by Yale University Press. Her other books include the acclaimed New York Times and international best seller Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books, as well as Things I’ve Been Silent About: Memories of a Prodigal Daughter and The Republic of Imagination: America in Three Books.